Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1979 | Volume 31, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1979 | Volume 31, Issue 1

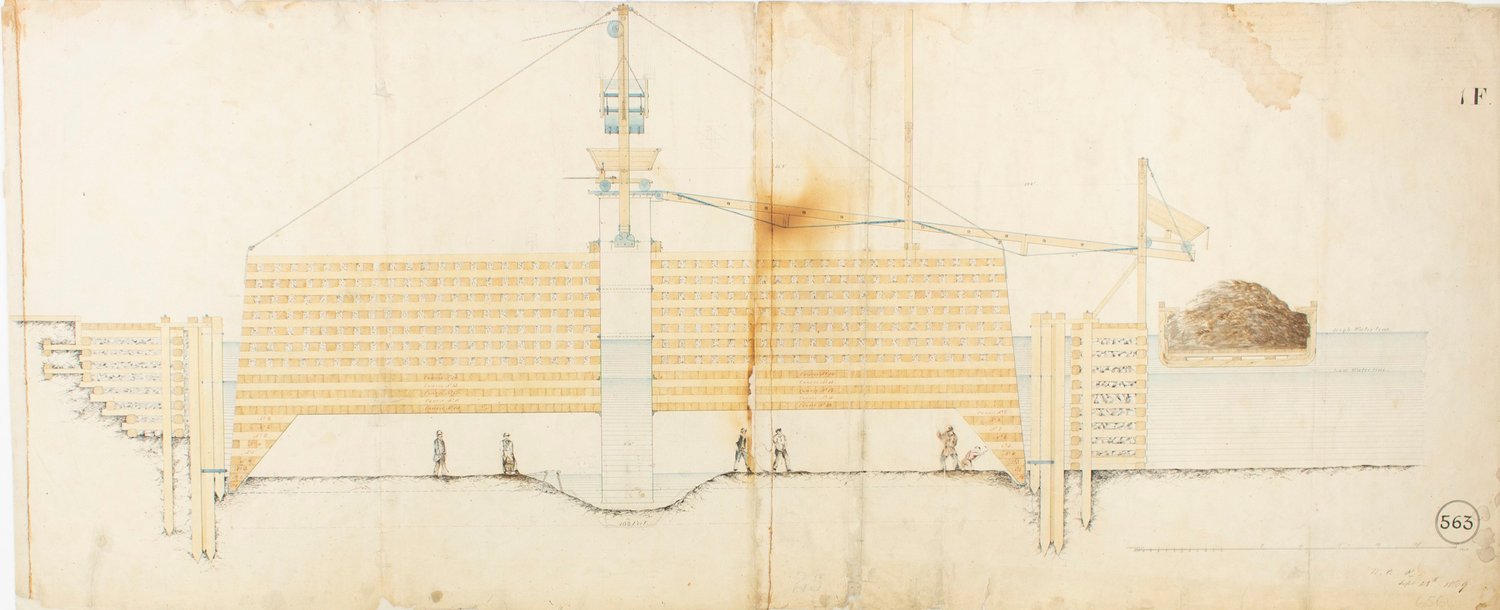

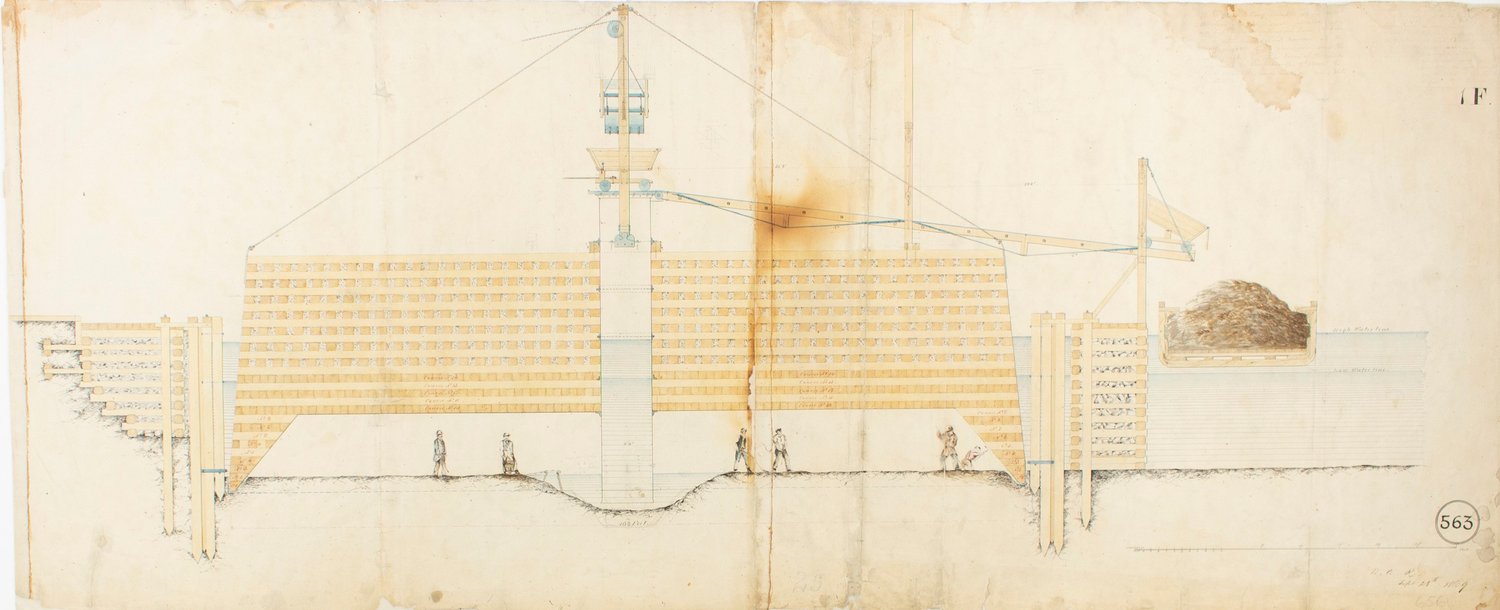

Early in 1969, because a bit of hardware on the Brooklyn Bridge had begun to show signs of wear after nearly ninety years, a young civil engineer working for the City of New York’s Department of Transportation was delegated to hunt up the original drawings of the item. The “trunnion,” as it is called, is a steel joint assembly, or gudgeon, about eighty of which are used to connect the vertical cables of the Brooklyn Bridge to the roadway out at the center of the river span where the greatest movement occurs. It is not an especially complicated or interesting device and it need concern us no longer, but like every other part and piece of the bridge, it had been custom-made to begin with and so could be replaced only by remaking it from scratch. Hence the need for the drawings.

Francis P. Valentine, the man sent for the drawings, was then twenty-nine years old, large and bearded, a native New Yorker and resident of Brooklyn who has been rightly described by his friend David Hupert as “an absolutely dedicated public servant.” His instructions were to go to the department’s carpentry shop at 352 Kent Avenue, a small, nondescript brick building beneath the Brooklyn end of the Williamsburg Bridge, and to look through the files that were in storage there. He was advised to wear old clothes, but he had no idea what to expect.

What he found, what he saw the morning he first walked into the shop, was one of the most remarkable treasures in the whole history of the building art, a collection like none other, totaling some ten thousand original blueprints and drawings, and what is so amazing is that for all the bewildering disorder they were in, the layers of dust and filth, he sensed almost at once the extent of their value. And in this he was the rare exception, for the drawings had been known to others in the department for nobody knows how long. Kept mainly for possible reference needs, for just such emergencies as the trunnion problem, they had been gone through, in part, by perhaps as many as twenty or thirty people at one time or another. Yet the idea that they might be worth something, that many were, in their way, magnificent works of art, not to mention historic documents of great consequence, had thus far failed to dawn on anyone of authority. In fact, one official, the engineer in charge of all East River bridges, previously