Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1977 | Volume 28, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1977 | Volume 28, Issue 4

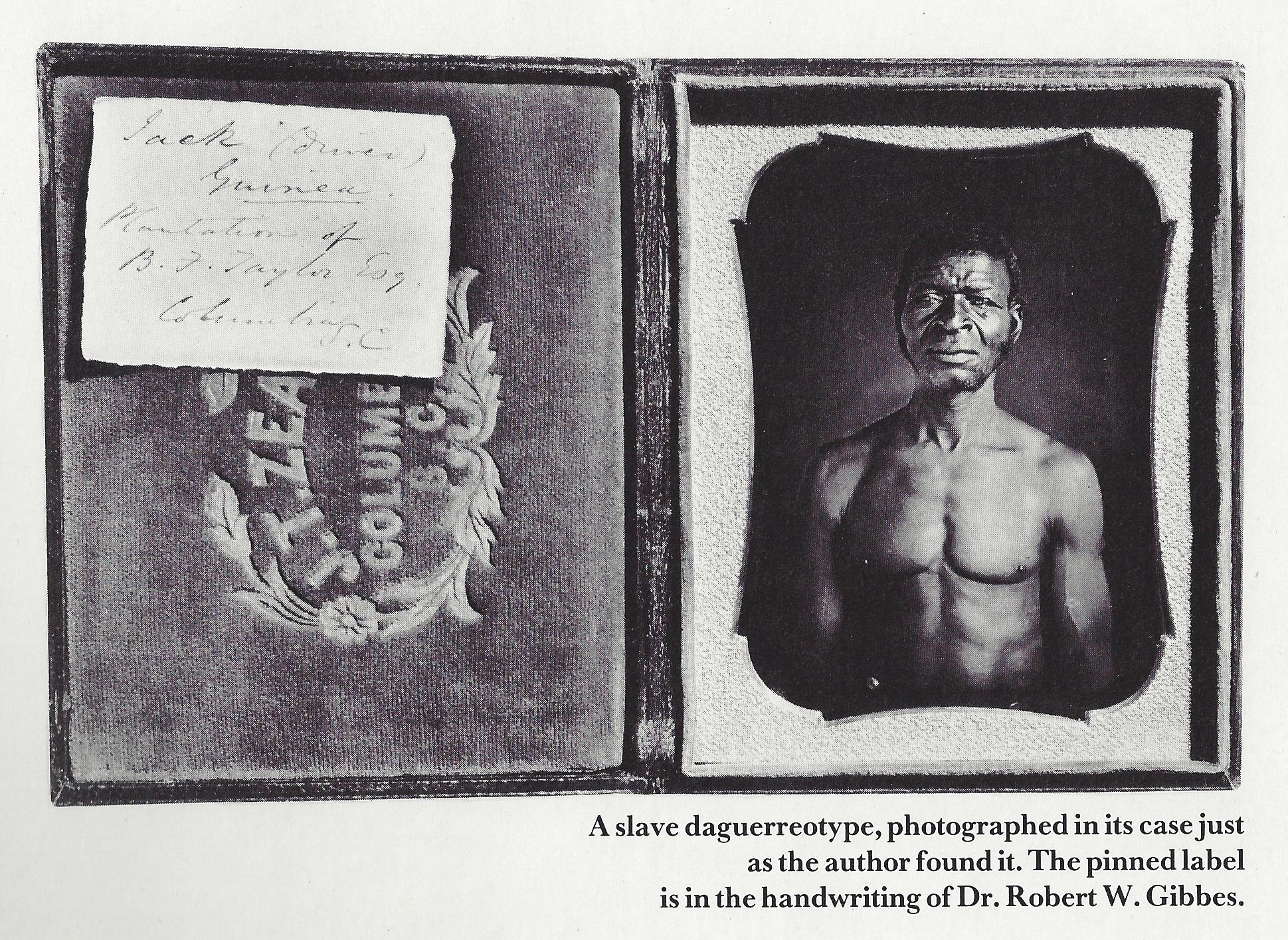

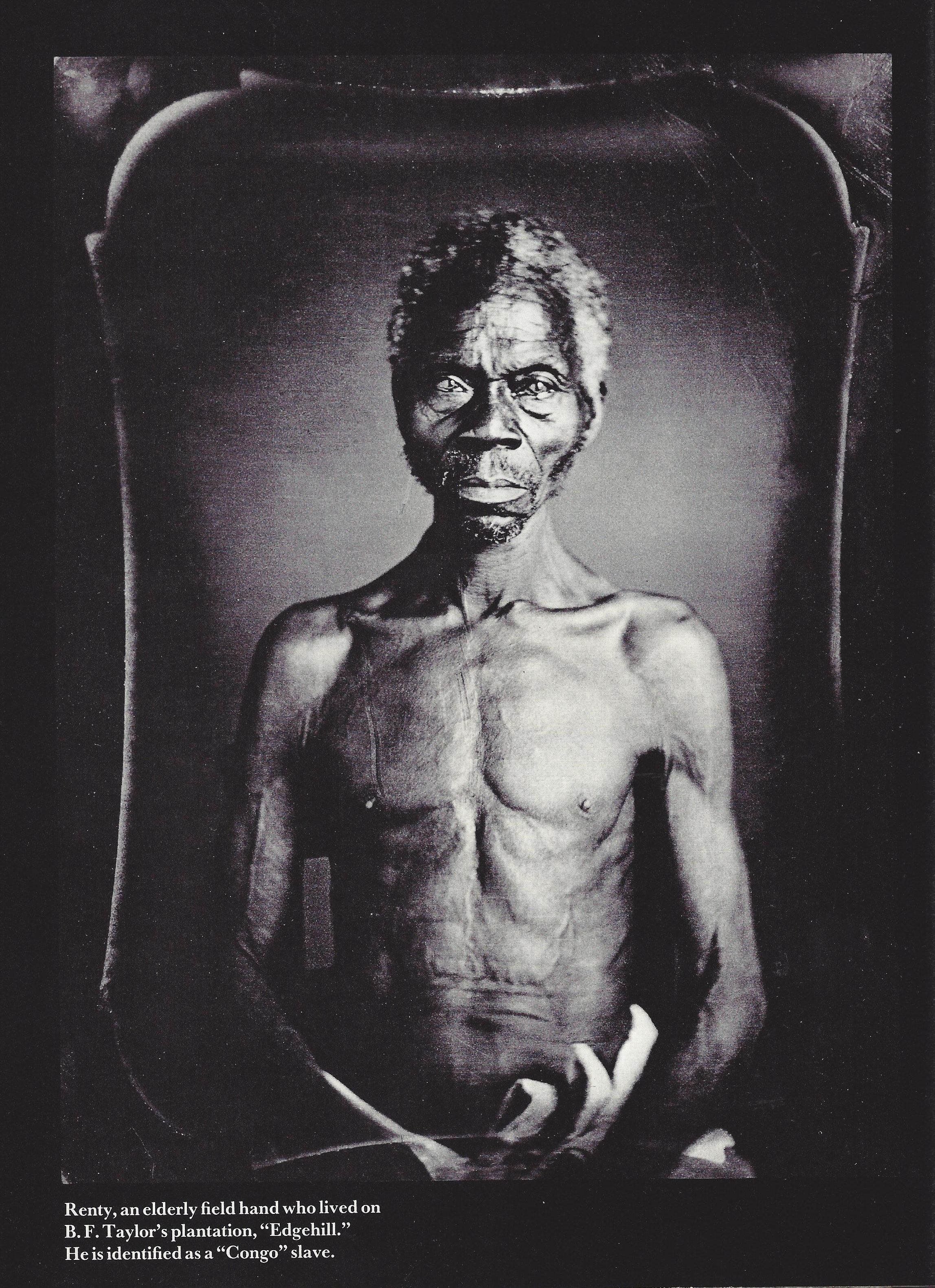

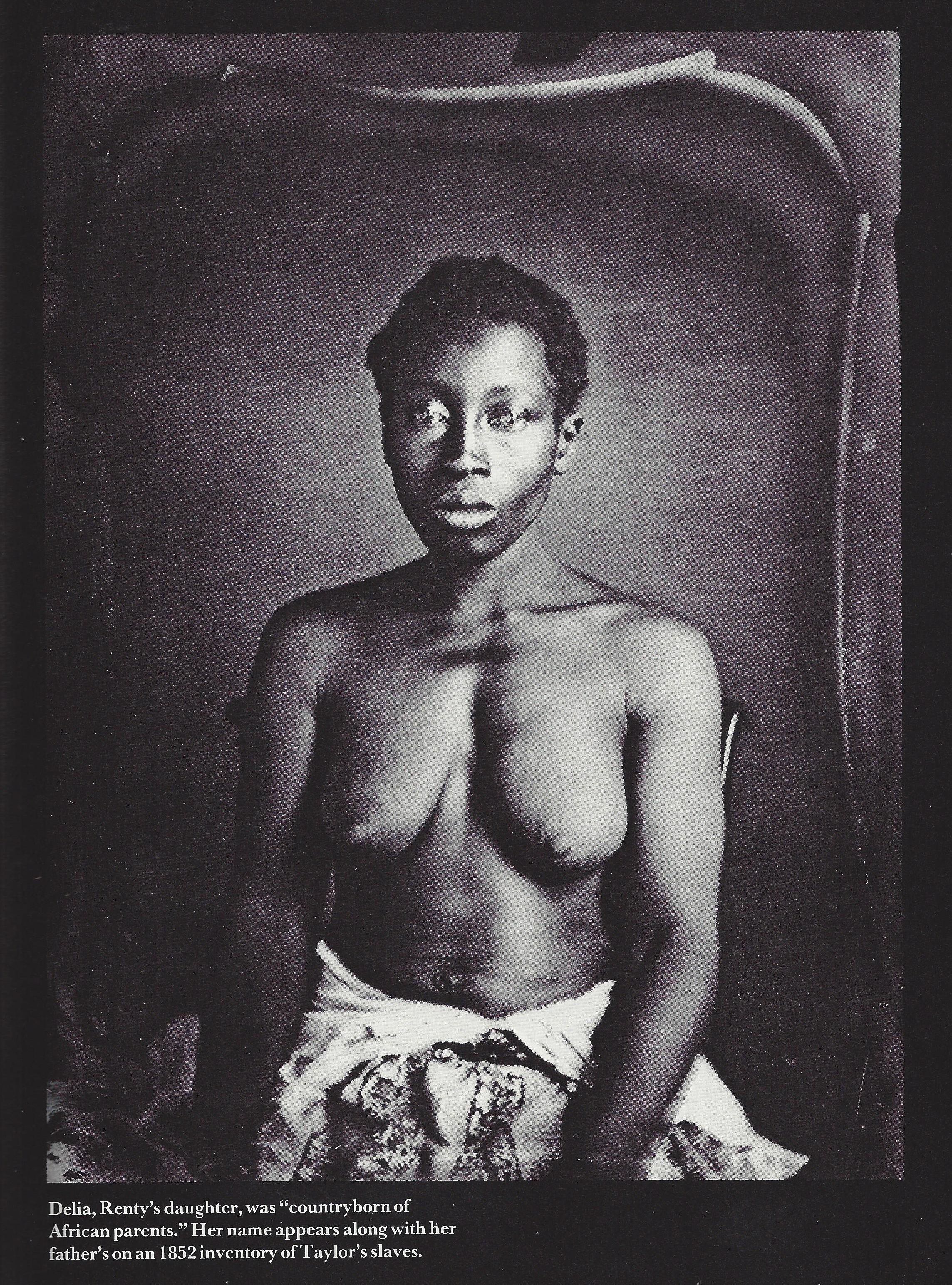

The six previously unpublished daguerreotypes on the following pages represent an extraordinary historical find. Made in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1850 at the behest of Louis Agassiz, the celebrated father of American natural science, they are among the earliest known photographs of Southern slaves. So far as we know they are also the earliest for which the subjects are identified by name and by the plantation on which each one toiled. And, perhaps most remarkable, all but one of the slaves they depict were born in Africa, and three can be identified with the tribe or region from which they came.

These pictures, part of a cache of fifteen, might have remained unknown had it not been for Elinor Reichlin, a former staff member of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, who found them early last year in an unused storage cabinet in the museum’s attic. Each daguerreotype case was embossed “J. T. Zealy, Photographer, Columbia” and several had handwritten labels. Nothing further was known about them. Ms. Reichlin spent months tracking down their story, and in the following article she explains just how and why these poignant images were made.

Until the late 1830’s, American scientists had little reason to question the Biblical explanation for mankind’s racial diversity. They assumed that all men were descended from the sons of Noah, who had dispersed across the world as the waters of the Great Flood receded. Racial differences were the result of centuries spent in different climates.

Then, Dr. Samuel Morton, an eminent Philadelphia anatomist, published two books, Crania Americana (1839) and Crania Aegypticus (1844), which seemed to cast doubt on mankind’s unity. After examining hundreds of ancient and modern skulls from both the Old World and the New, he noted that each region had been peopled by distinct races since antiquity. The Biblical time allotted to man’s dispersal was far too short to account for such an ancient and extensive settlement of two widely separated continents by distinct races. Therefore, he reasoned, “mankind” must not be one species but several, each specially created by God to suit its own geographical environment.

Abolitionists decried