Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1977 | Volume 28, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1977 | Volume 28, Issue 3

Americans have always assumed that scalping and Indians were synonymous. Cutting the crown of hair from a fallen adversary has traditionally been viewed as an ancient Indian custom, performed to obtain tangible proof of the warrior’s valor. But in recent years many voices—Indian and white—have seriously questioned whether the Indians did in fact invent scalping. The latest suggestion is that the white colonists, in establishing bounties for enemy hair, introduced scalping to Indian allies innocent of the practice.

This theory presupposes two facts: one, that the white colonists who settled America in the seventeenth century knew how to scalp before they left Europe; and two, that the Indians did not know how to scalp before the white men arrived. But are these facts? And if they are not, who did invent scalping in America?

Total silence from both participants and historians casts doubt on the first proposition. For no one has ever insinuated, much less proved, that the European armies who fought so ruthlessly the Crusades, the Hundred Years’ War, and the Wars of Religion ever scalped their victims. Even when they were combating a European form of “savagery” in Ireland, Queen Elizabeth’s forces were never scalped or ever took scalps. The grim, gray visages of severed heads lining the path to a commander’s tent were more terrible than impersonal shocks of hair and skin.

Nor does the second proposition fare much better. For there is abundant evidence from various sources that the Indians practiced scalping long before the white man arrived and that they continued to do so without the incentive of colonial cash.

The first and most familiar source of evidence is the written descriptions of the earliest European observers, who presumably saw the Indian cultures of the eastern seaboard in something like an aboriginal condition. When Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence to what is now Quebec City in 1535, he met the Stadaconans, who showed him “the scalps of five Indians, stretched on hoops like parchment.” His host, Donnacona, told him they were from “Toudamans from the south, who waged war continually against his people.”

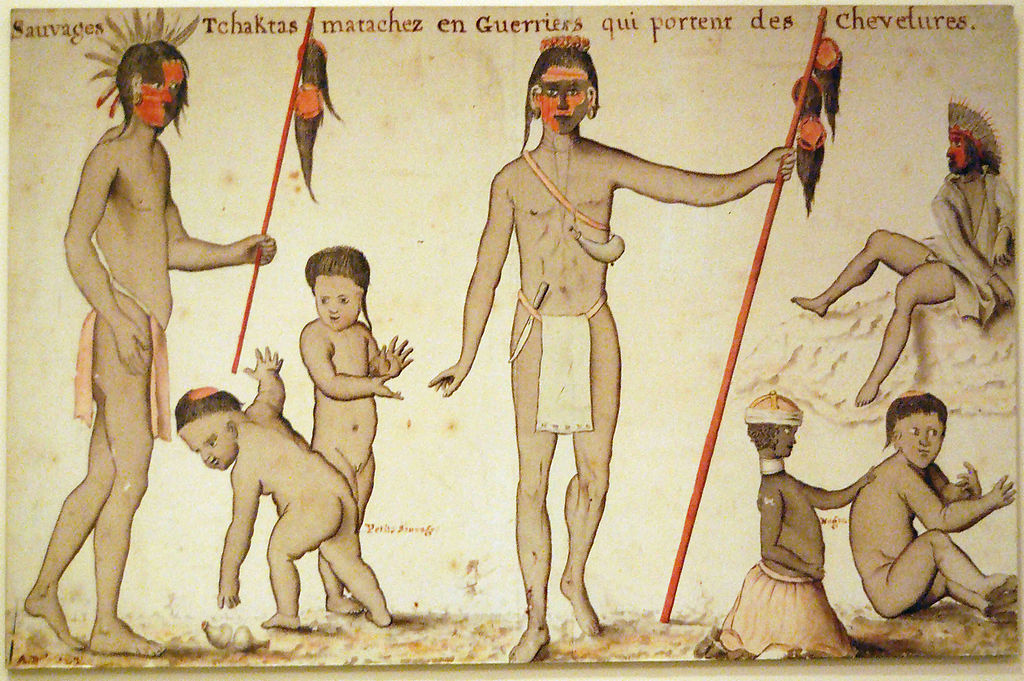

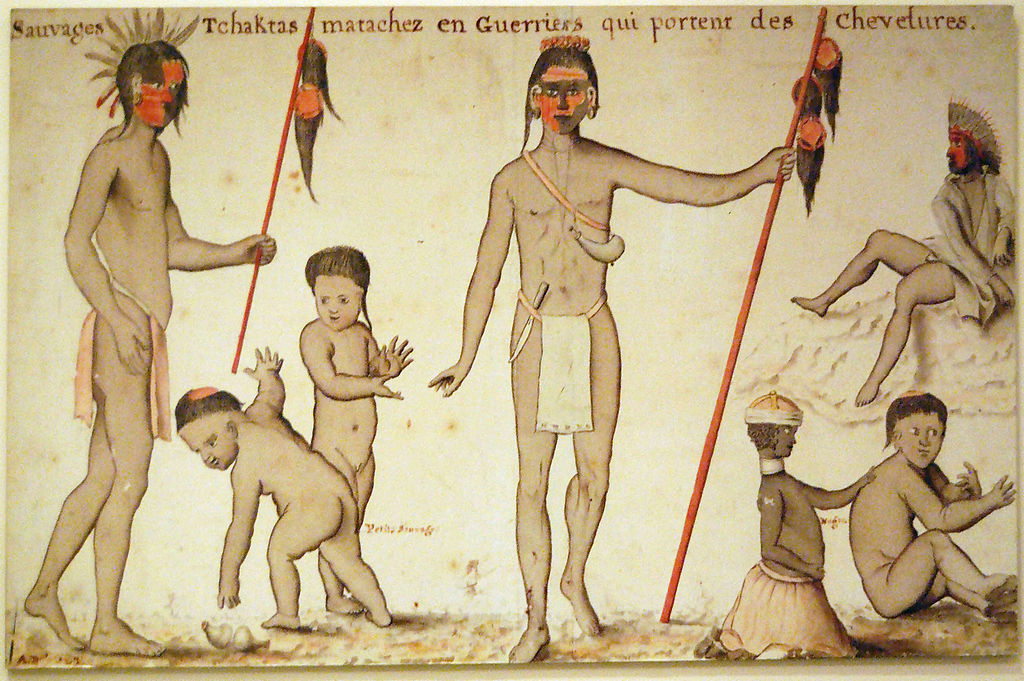

Twenty-nine years later, another Frenchman, artist Jacques Ie Moyne, witnessed the Timucuans’ practice of scalping on the St. Johns River in Florida:

"They carried slips of reeds, sharper than any steel blade … they cut the skin of the head down to the bone from front to back and all the way around and pulled it off while the hair, more than a foot and a half long, was still attached to it. When they had done this, they dug

When they arrived at their village, they held a victory ceremony in which the legs, arms, and scalps of the vanquished were attached to poles with “great solemnities.”

The French were not alone in witnessing the Indian custom of scalping. When the English brazenly set themselves down amid the powerful Powhatan Confederacy in Virginia, the Indians used an old tactic to try to quash their audacity. In 1608 Powhatan launched a surprise attack on a village of “neare neighbours and subjects,” killing twenty-four men. When the victors retired from the scene of battle, they brought away “the long haire of the one side of their heades [the other being shaved] with the skinne cased off with shels or reeds.” The prisoners and scalps were then presented to the chief, who hung “the lockes of haire with their skinnes” on a line between two trees. “And thus,” wrote Captain John Smith, “he made ostentation … , shewing them to the English men that then came unto him, at his appointment.”

The first Dutchmen to penetrate the Iroquois country of upstate New York also found evidence of native scalping. When the surgeon of Fort Orange (Albany) journeyed into Mohawk and Oneida territory in the winter of 1634-35,ne saw atop a gate of the old Oneida castle on Oriskany Creek “three wooden images carved like men, and with them … three scalps fluttering in the wind.” On a smaller gate at the east end of the castle a scalp was also hanging, no doubt to impress white visitors as well as hostile neighbors.

The list of Europeans who upon first meeting the eastern Indians found scalping prevalent is a long one. The first characteristic their descriptions share is an expression of surprise at the discovery of such a novel custom. The nearly universal highlighting of the custom in early accounts, the search for meaningful comparisons (such as parchment), the detailed anatomical descriptions of the act itself, and the total absence of any suggestion of white familiarity with the practice all suggest that their surprise was not disingenuous.

The second theme of these descriptions is that scalping was surrounded by a number of rituals and customs that could hardly have been borrowed from the freebooting European traders and fishermen who may have preceded the earliest authors. The elaborate preparation of the scalps by drying, stretching on hoops, painting, and decorating; scalp yells when a scalp was taken and later when it was borne home on raised spears or poles; occasional nude female custodianship of the prizes; scalp dances and body decorations; scalps as nonremunerative trophies of war to be publicly displayed on canoes, cabins, and