Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 1975 | Volume 26, Issue 6

Authors: Allan L. Damon

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 1975 | Volume 26, Issue 6

Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! All persons having business before the Honorable, the Supreme Court of the United States are admonished to draw near and give their attention, for the Court is now sitting! God save the United States and this Honorable Court!” On October 6—the first Monday of the month—those venerable words will herald the opening of the 1975–76 term of the Supreme Court of the United States, which has long been revered as the bulwark of our constitutional system. We offer here a portrait of its role in the American past.

The Supreme Court of the United States is easily the most respected and least known branch of the federal government. Once a poor relative of the Presidency and Congress, it has emerged as the pre-eminent defender of the Constitution and the chief protector of the principles of due process that underlie the Republic. Its authority reaches into every state and community across the nation, and the force of its opinions has dramatically altered contemporary life.

For all of that, the Court remains wrapped in mystery, known only by its outward forms. Its deliberations are carried on in secret, and its members are bound by custom to maintain strict silence about their work together. Only the barest public record of their discussions is ever published. Answerable in most instances only to themselves, the justices of the Court seemingly operate with near-total independence.

There is, in fact, a classic irony in the Court’s role as the guardian of democracy and individual rights, for in reality it is an elitist institution. Its membership does not reflect the population as a whole; its internal policies are generally not affected by outside influences; and its actions are often only marginally and indirectly controlled by Congress and the states. It is, by any measure, the least accessible of any governmental agency other than the CIA or the intelligence units of the armed services.

But its existence within a democratic republic is no accident, if only because the American people, from colonial times onward, have had a continuing love affair with the law. Long before the Revolution and for many years afterward travellers from abroad were consistently struck by the litigious nature of American life and the familiarity of even the most rural people with the intricacies of legal argument. “In no country perhaps in the world is the law so general a study,” Edmund Burke remarked to Parliament in 1775. “The profession itself is numerous and powerful. … But all who read, and most do read, endeavour to obtain some smattering in that science.”

Whatever the reason for such interest—some,

Through the long struggle with Great Britain that belief in the primacy of law prevailed, and the colonists automatically resorted to the courts for relief from the oppressive acts of Parliament or from infringements on their charter rights. Almost instinctively they turned to petitioning and other forms of legal redress as their chief means of protest before they resigned themselves at last to the necessity of armed conflict. As the townspeople of Pelham, Massachusetts, put it in 1773, the American cause was meaningless unless it was secured “by lawful and constitutional measures.”

When the Founding Fathers gathered at Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to revise the Articles of Confederation, they were well aware of the many weaknesses in the existing government, particularly the absence of a national court system and what Alexander Hamilton called a “uniform rule of civil justice.” During the Revolution full judicial power had been lodged in the separate states—with two exceptions. Congress had been given authority to establish courts for trial of admiralty cases arising on the high seas and was itself authorized to serve as a court of final review in boundary and other jurisdictional disputes among the states, but only on petition from the state or states involved. As the delegates to the Constitutional Convention saw it, this was tantamount to no authority at all, and they were determined to supply a corrective.

After weeks of debate they settled on a bare grant of power that in its spareness belies the extraordinary influence the Supreme Court has come to exert. As provided for in Article in, Section 1 of the Constitution, “The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”

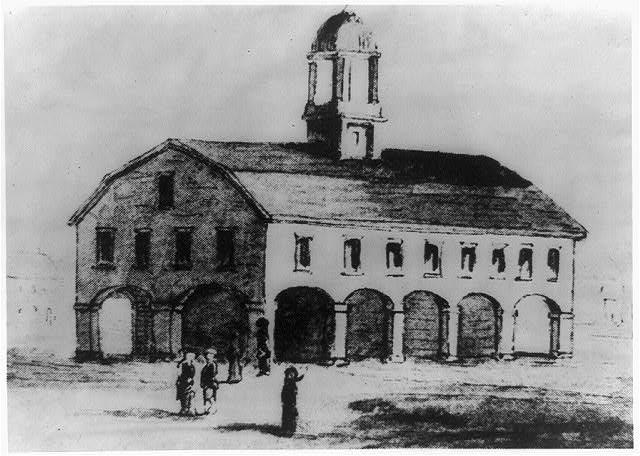

Brought to life by the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Court took up its duties on February 2, 1790, in the old Royal Exchange at the foot of Broad Street in New York. Despite the splendor of this occasion—John Jay, the forty-four-year-old Chief Justice, was handsomely clothed in “an ample robe of black silk with salmon colored facings,” and the other four justices present were similarly arrayed—it was clear to everyone

For the next decade the bleakness of that record remained unchanged. The Court was the backwater of the legal world; few issues of consequence came before it, and the nation’s legal talent generally turned its attention to the state courts or, on the federal level, to Congress. Of the hrst fourteen appointees to the Court five (includingjohn Jay) resigned after relatively short terms, one failed of Senate confirmation, and three refused outright the opportunity to serve. When the new government moved to Washington in 1800, the low prestige of the Court was visibly demonstrated by the architects’ failure to provide it with a chamber in the new Capitol. Eventually—and rather hastily—quarters were established in a small room (twentyfour by thirty feet) on the building’s main floor, just in time for the 1801 term.

That term proved to be the turning point in the Court’s history, for it was marked by the appointment of John Marshall as Chief Justice. Despite some initial resistance from Federalists who had hoped to see an associate justice promoted—one senator recorded that he had heard the news of Marshall’s nomination “with grief, astonishment and almost indignation”—the Senate voted unanimous approval and thereby set the stage for a dramatic reversal of the judiciary’s fortunes.

Over the next thirty-four years, as the volume of cases increased, the great Virginian made the Court an effective instrument and a central force in the government. Beginning with Marbury v. Madison (1803), which established the principle of judicial review for federal legislation, and continuing with Fletcher v. Peck (1810), which carried that principle to the states, Marshall delivered a series of magisterial opinions that confirmed the primacy of federal power and, more importantly, made the Court a coequal branch with the Presidency and Congress. By the time of his death in 1835 the high bench had earned a respect that through the next century grew into something approaching reverence.

In our own day the Supreme Court sits at the apex of a judicial system unlike any other in the world. The cornerstone of its authority is its power to review the constitutionality of statutes emanating from Congress and the state legislatures. But it draws an equal measure of eminence and strength from its constitutional charge as the court of last resort, in a jurisdiction that extends to the courts of the

Herewith some highlights and details.

Appointment to the Supreme Court is made by the President “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate.” Because there are no statutory requirements for the federal judiciary at any level, the selection process is inevitably colored by a number of complex personal and political considerations that vary with each executive, particularly in determining the ideological make-up of the Court.

Nonetheless there are certain traditional—if informal—guidelines that may control a President’s choice, among them the unwritten rule that only a lawyer may be elevated to the high bench; that a nominee must be personally acceptable to his home-state senators and preferably to the Senate leadership as well; that the nominee’s public career shall be sufficiently distinguished to warrant his appointment. In addition, a variety of geographical, religious, and educational factors are given weight. For example, in the last forty years one seat has been customarily designated as Roman Catholic and another as Jewish, although a President may ignore the custom, as Mr. Nixon did in 1969 when he replaced Mr. Justice Fortas with a Protestant.

Membership on the Court is currently set at nine. The figure is determined by Congress and in the early years fluctuated with the ebb and flow of the Court’s business and prestige. The Judiciary Act of 1789 initially fixed the number at six. This was reduced to five in 1801 and then raised to six in 1802, to seven in 1807, to nine in 1837, and still further to its highest level, ten, in 1863. The membership was cut to seven in 1866. The current figure was established in 1869. In 1937 Franklin Roosevelt

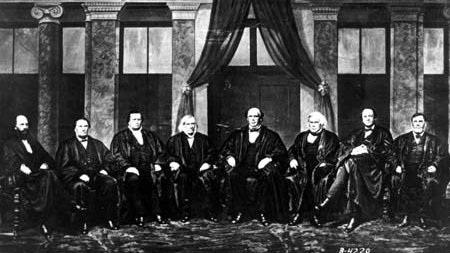

Exactly one hundred men have served on the Court to date, fifteen of them as Chief Justice. No woman has ever been presented for appointment, and leading minority groups have generally been ignored. As a result the Court historically reflects a homogeneous profile much like that associated with the Presidency.

The most striking feature in the Court’s membership—and perhaps the most surprising—is its historic lack of judicial experience. Nearly half (forty-seven) of the hundred justices had never served in a judicial role prior to their appointment to the Supreme Court. Of those with service on the state or federal bench only twenty-two had ten or more years of experience. Among the Chief Justices six had no prior court service, including John Marshall, Roger B. Taney, and Earl Warren. On the current Court, Chief Justice Burger and Associate Justices Stewart, Marshall, and Blackmun all served on the courts of appeals.

Forty-nine of the justices have been officeholders at the state or federal level. Sixty have worked at one time or another for the federal government, thirty-five of them in the executive branch. Thirteen have served in Congress and six in their state legislatures. Another thirteen were primarily corporation lawyers before appointment to the bench, and eight were primarily in private legal practice. Four were law professors—all of them appointed by Franklin Roosevelt: Harlan Fiske Stone (Chief Justice), Felix Frankfurter, Owen J. Roberts, and William O. Douglas. On the current Court, Associate Justices White and Rehnquist served in the office of the United States Attorney General, Mr. Justice Brennan on the New Jersey Supreme Court, and Mr. Justice Powell as a lawyer in private practice before appointment.

Tenure on the Court is for life “during good Behaviour.” This provision of Article m of the Constitution is the principal source of judicial independence at all levels of the federal system and means that except for removal through impeachment judges are free to serve as long as they wish. There is no provision for the removal of sick or disabled justices on the Supreme Court; the decision to leave the bench is thus a matter of individual conscience.

Like others in the federal judiciary, the justices of the Supreme Court may retire at

Among the ninety-one justices who have left the Court to date, forty-eight died in ofhcc, twenty-three retired, sixteen resigned, three were disabled, and one, John Rutledge, was !ejected by the Senate even though he had served one month as Chief Justice while Congress was in recess.

In this century six justices have resigned from the Court: Charles Evans Hughes in 1916 to run for President (he returned as Chief Justice in 1930); John H. Clarke in 1922 to work for world peace; James Byrnes in 1942 to head a succession of wartime agencies, ending as Secretary of State; Owen J. Roberts in 1945 to become dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School; Arthur Goldberg in 1965 to become United States ambassador to the United Nations; and Abe Fortas in 1969 to return to private law practice.

Since 1789 only one Supreme Court justice has been impeached. In 1804 the Jeffcrsonian Republicans in the House charged that the arch-Federalist Samuel Chase had made political remarks from the bench that impaired “confidence and respect for the courts.” Chase was acquitted by the Senate.

Among recent retirements perhaps the most notable was (hat of Tom (Hark in 1907, who applied for early retirement in order to avoid any conflict of interest in cases brought to the Court by his son, Ramsey Clark, who had been appointed Attorney

Rejected nominations are a commonplace in the history of the Court. Since 1789 thirty-four appointments to the high bench have failed to take effect, usually for one of three reasons: the Senate refused confirmation, the President withdrew the nominee’s name in the face of certain Senate refusal, or the nominee himself declined to serve. Placed against a total of 138 nominations, this works out to an astonishing rejection rate of about I in 4, or 24 per cent of all Supreme Court appointments.

Despite assurances they would be confirmed, seven of the nominees simply refused to serve, all of them liefore 1883 and five of them in the first quarter century of the Court’s existence. The reasons vary for each man, of course, but generally the refusals fall into two categories. Some merely found the work of the Court not to their liking because it was too arduous, or not challenging enough, or lacking in prestige. John Jay, for example, resigned as Chief Justice in 1795 to become the governor of New York. When President John Adams offered to reappoint him to the federal post in 1801, Jay turned it down because he did not want to ride the circuit—that is, to travel through the country to hear appeals from the trial courts, as justices of the Supreme Court were required to do until the creation of the courts of appeals in 1801. On the other hand, John Quincy Adams refused appointment as an associate justice in 1811 because he thought his legal experience did not qualify him for the position. In 1882 Roscoe Conkling, the last of the seven, declined to serve as Chief Justice for the same reason.

Twenty-seven nominations from fifteen Presidents failed to secure Senate confirmation. Five of these rejections occurred in this century, four of them in the last decade.

What lies behind these twenty-seven rejections is a number of complicated, discrete, and long-forgotten political differences between the President and the Senate. At issue is the appointive power in Article u of the Constitution. The Presidents generally have held that the power is exclusively theirs—that in effect the Senate has no

What led the Senate to block the appointments of these twenty-seven men, including four Chief justices, is not easily summarized. Undoubtedly some of the rejections proceeded from the conviction that the President’s nominee was not fit for the Court—a prejudice that sometimes can be overcome: in 1887 the Senate divided over the appointment of Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, a former senator from Mississippi, who had served in the Confederate army. A sixty-two-year-old widower, Lamar was criticized severely for his relationship with a young woman in her twenties, who, as it happened, had been accused of arson. A sufficient number of senators took the broadminded position that Lamar was as innocent as he claimed to be, and in the end his appointment was confirmed by a vote of 32 to 28.

More often than not, however, the Senate’s refusal to confirm has been nothing less than raw politics and as such forms a rather special chapter in the continuing struggle between the President and Congress for power. John Rutledge, for example, was denied the Chief Justice’s seat in 1795 as much because he had openly opposed the Jay Treaty with England as because there were well-founded rumors that he had become mentally deranged. Since the treaty was a pet project of the Federalists and Rutledge had broken party ranks with his denunciation of it, some Federalist senators, at least, voted to reject as a form of punishment.

Similarly, Roger B. Taney, who became Chief Justice in 1836 on the death of John Marshall, was denied a seat as associate justice in 1835 because of Senate anger at Andrew Jackson’s assault on the Bank of the United States. Because Taney, who was otherwise qualified for the Court, had accepted the task of removing deposits from the bank, the Senate voted to postpone his initial appointment. Emotions had cooled somewhat the following year, for his appointment as Chief Justice passed easily by a vote of 29 to 15.

John Tyler’s unhappy administration provides the clearest example to date of politics at work in the rejection of Court appointees. The first Vice President to succeed to the Presidency on the death of an incumbent, Tyler had to contend for four years with the jibe that labelled him “His Accidency, the President.” A Whig, he had fallen into disfavor with his party, the congressional members of which had already censured him in a caucus vote, and he had narrowly escaped an impeachment resolution in 1842. Thus it was no surprise when the Whig-dominated Senate rejected four consecutive appointments to the Court in

Five appointments have failed in the twentieth century, and several others have come close to rejection. When Louis Brandeis was presented to the Senate by Woodrow Wilson in 1916, five months of bitter political infighting were required to offset the anti-Semitic opposition that threatened to prevent the appointment of the first Jew to the Court. In the end Brandeis triumphed by a vote of 47 to 22.

The first justice rejected in this century was John C. Parker, nominated by Herbert Hoover in 1930. During the confirmation hearings it was learned that Parker ten years earlier had delivered a speech in a gubernatorial campaign in North Carolina, in which he asserted that blacks in politics were “a source of evil.” That remark, coupled with his antilabor record while serving in the North Carolina courts, doomed his appointment. Ironically, the most recent appointment to fail did so for much the same reason. A campaign speech in support of white supremacy in 1948, joined to an undistinguished judicial record in the United States Court of Appeals, led to the rejection of Richard Nixon’s appointment of G. Harrold Carswell in 1970.

That failure to confirm gave Nixon the distinction of being the first President since Grover Cleveland in 1894 to lose two consecutive appointments. Earlier in 1969 the Senate had voted to deny Clement C. Haynesworth a seat on the Supreme Court because—as one senator put it—he was not sensitive to “the appearance of impropriety.” At issue was a controversial case in which Haynesworth, as a judge on the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, had failed to disqualify himself, although there was a potential conflict of interest because of certain stocks he owned. Haynesworth’s own honesty was not in question; his sense of ethical conduct was, and given the climate of the time, even the hint of impropriety was sufficient cause for rejection.

What had produced that climate was the century’s most sensational case involving a justice of the Supreme Court. Abe Portas, already an associate justice, had been selected by Lyndon Johnson in the summer of 1968 to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice. Despite a distinguished public career, both as a member of the government and as a corporation counsel, Fortas’ nomination ignited the Senate. Some Republicans were incensed that the President, who had already announced he would not seek re-election, would have the opportunity to fill the central seat on the bench, and they urged that no appointment be made until a new executive had taken office in 1969. Southern conservatives, led by Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, were already distressed

Expenses of the Supreme Court in the current fiscal year total about $6.5 million, an increase of more than $1 million over the appropriation in 1973. (The budget for the federal judiciary as a whole now exceeds $210 million, up from $126 million in 1970 and $194 million in 1973.)

Approximately 75 per cent of the Court’s expenses—or nearly $5 million—covers the cost of salaries and benefits for some 350 employees, including 290 clerks, secretaries, librarians, etc., a guard force of 33 uniformed officers, and a maintenance staff of 30.

The eight associate justices receive $60,000 each in salary, the Chief Justice, $62,500. That pay scale has been in effect since 1969 and represents the seventh increase in this century. Typical salaries of the associate justices in the past were: 1878, $10,000; 1926, $20,000; 1946, $25,000; 1964, $39,500. The Chief Justice each time got an additional $500.

About $600,000 is spent annually to print the various reports of the Court’s opinions in its own printing shop. Given the importance of these documents—advance word in an antitrust case, say, could mean millions of dollars to investors—it is remarkable that the Court has never had a breach of security in this century, either from its printers or for that matter from any of its employees.

The remainder of the Court’s budget is spent on books, equipment, and supplies (the greater part of which are used in the maintenance of its building). Something of an itinerant Court in the early years, the justices were housed from 1810 to 1860 on the first floor of the Capitol, after which they occupied the old Senate chamber when the senators took possession of the new wing of the Capitol in 1861. They entered their present building in 1935.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, as provided for in Article in of the Constitution, extends “to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties. …” Although most cases

At the present time this means that the Court is in a position to review the work of

The key power is, of course, judicial review, which is the right of the Supreme Court to hold state and federal law in conformity to the Constitution. And it is this authority that sets the Court apart from the high tribunals in other lands. In England, for example, there is no such power because there is no written constitution; an act of Parliament cannot be in violation and must be enforced. As a result England’s chief tribunal, the Court of Appeals, is empowered only to interpret the law as it has been applied in the lower courts.

The Supreme Court is under no such limitation, but it does not work with a free hand and like other branches of the federal government is subject to the system of checks and balances and to its own self-imposed restraints. Two are of major importance: the Court will accept only those cases that involve “a substantial Eederal question” and, secondly, will not render a decision in advance or independently of an actual case or controversy. This last was set as Court procedure—unbroken since—in 1793, when John Jay, speaking for his associates, informed George Washington that the Court could not speak “extra-judicially” in giving him advice about certain matters of international law.

At the present time some 4,200 cases come before the Supreme Court each year. Roughly half are so-called pauper cases directed to the Court from prisoners seeking

What this means is lhat the Supreme Court ultimately confronts only a fraction of the civil and criminal cases that enter the federal judicial system. At the present time approximately 140,000 cases annually enter the district courts. Nearly 99,000 are civil cases, and of these perhaps 10 per cent (about 9,500) will reach trial. Some 40,000 criminal cases enter the system each year, about a fourth of which will reach trial. The courts of appeals currently accept about 15,600 cases for review, of which nearly half are given formal consideration.

There is, of course, no guarantee that the Supreme Court’s opinions will have an immediate effect on the nation as a whole when any of these cases is finally decided, for among the powers denied the Court is any real means oi” enforcement. Congress can overrule the Court through constitutional amendment or by further statutory enactment. Under our system of dual federalism the states mayturn, as they have several times in the past, to the doctrine (now discredited) of nullification. Or, as the history of compliance with the Court’s school-desegregation decisions shows, they can resort to loot-dragging and delay in implementing Court orders—tactics reminiscent of Andrew Jackson’s refusal to prevent the removal of Cherokee Indians from Georgia in 1832, when he allegedly said: “John Marshall has made his decision; let him enforce it.” Since 1789 there have been a number of schemes proposed—from the abolition of the Court entirely to Theodore Roosevelt’s proposal that controversial decisions be subjected to a national referendum—to curb excessive judicial power.

But on the whole, the Court’s power has been visible and effective, primarily because the American people have been willing to accept the primacy of law and the moral suasion that the Court consistently reflects.

Despite recurring reservations about its secrecy and the elitism it engenders, in spite of persistent complaints that the Court has sometimes run counter to prevailing sentiment or ignored pressing social ills, the nation historically has embraced the judgment Alexis De Tocqueville rendered more than a century ago: “The peace, prosperity, and very existence of the Union rest continually in the hands of these … federal judges. Without them the Constitution would be a dead letter. …”

For Further Reading: