Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1975 | Volume 26, Issue 3

Authors: Brian W. Dippie

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1975 | Volume 26, Issue 3

In the summer of 1885 a young artist from New York by way of Kansas City found himself resting by a campfire with a couple of prospectors out in Arizona Territory at a time when Geronimo was on the prowl, perhaps “even in our neighborhood.” It was about 9 o’clock in the evening, and the three men were drowsily relaxing, puffing on their pipes and looking up at the stars through the branches of the trees overhead. Suddenly, the artist later recalled, “my breath went with the look I gave, for, to my unbounded astonishment and consternation, there sat three Apaches on the opposite side of our fire with their rifles across their laps.” His companions spotted the Indians at about the same time, and “old, hardened frontiersmen as they were, they positively gasped in amazement.” Before the white men could react and get their guns out, the Indians assured them they had come in peace and wanted only flour, not a fight. Yet they stayed by the fire all night, making it sleepless for the artist and the two prospectors. When the Indians pulled out in the morning, “I mused over the occurrence,” the narrator went on, “for while it brought no more serious consequences than the loss of some odd pounds of bacon and flour, yet there was a warning in the way those Apaches could usurp the prerogatives of ghosts, and ever after that I used to mingle undue proportions of discretion with my valor.”

So Frederic Remington opened another of his patented essays on western life for his rapidly growing audience in the East. He was writing in 1889, at a time when his name was still not synonymous with the far frontier, though after three years of ever more frequent exposure in some of the most popular magazines of the day he was quickly establishing a reputation that would make him, for most Americans, the supreme interpreter of the Wild West. Moreover, Remington already had his approach shrewdly worked out. The extended anecdote about the uninvited Apache guests served to launch an article entitled “On the Indian Reservations.” It was, fundamentally, a rather routine account of some firsthand observations made among the Apaches, Comanches, Kiowas, and Wichitas. Nothing of particular note happened to Remington, nothing truly exciting to enliven his report and grip his readers with that sense of peril that was the better part of the Wild West mystique. So Remington provided it himself, drawing his readers into his narrative by creating at the outset a siege mentality that would give them the thrill of vicariously participating in a daring adventure. Who knew what dangers still lurked in the dark shadows of Indian country? It was a bait, expertly administered;

Frederic Sackrider Remington was born on October 4, 1861, in the small town of Canton in upper New York State. The Civil War was not yet six months old, and it would be over before Remington was four. Nevertheless it seems to have left a definite impression on him, for his father, a Republican journalist who owned the local newspaper, was a major in the 11 th New York Cavalry and came back from the war with a wealth of stories to tell about fighting in Virginia and Louisiana. From an early age Remington was steeped in the lore of combat and had formed an interest that he would never relinquish. In 1897, long after he was established as the artist-historian of the Indian-fighting army, he was still chasing the smell of battle. “We are getting old,” he wrote a friend, “and one cannot get old without having seen a war.”

Two other lifelong interests were shaped by Remington’s boyhood. With a father who was not only an ex-cavalryman but a harness-racing enthusiast as well, Remington grew up around horses. As an adult he confessed that he “always likefd] to dwell on … [the] subject of riding” and had “an admiration for a really good rider which is altogether beyond his deserts in the light of philosophy.” His work reflected that fact, as did his oft-repeated choice for an epitaph: “He knew the horse.” Remington’s upstate New York boyhood was also an education in the outdoors. Fishing, hunting, swimming, canoeing, hiking, and camping were the normal recreations of a boy from his region. The Adirondacks, his beloved Cranberry Lake, and the rivers and streams that interlaced the area became part of Remington’s mental landscape, and he cherished an abiding passion for the north woods that found fulfillment when, near the end of the century, he acquired an island of his own, Ingleneuk, in Chippewa Bay on the St. Lawrence River. There for a decade he passed many of his happiest hours, painting, relaxing, and enjoying a “summer” break from the city that some years stretched from March to October. The north country, where he grew up and is buried, rather than the West, with which he is so intimately identified, remained home in Remington’s heart. It bred in him those tastes that eventually drew him westward. “A real sportsman, of the nature-loving type,” he wrote, “must go tramping or paddling or riding about over the waste places of the earth, with his dinner in his pocket.”

A fascination with the military, horses, and the outdoors was thus a hallmark of Remington’s career until he died. They represent a constancy that is revealing about him, both as man and as artist, and help explain why one army officer in 1890 described him as “a big, good-natured, overgrown boy.” For by the time Remington entered the Highland Military Academy at Worcester, Massachusetts, in the fall

He was by this time already a husky, thickset young man, sandy-haired, smooth-faced, and blue-eyed. His features, dominated by a prominent nose and a rather sullen mouth, were not especially attractive; but he was physically prepossessing, with the neck of a heavyweight boxer and the muscular build of a natural athlete. In an amusing selfassessment, written with his characteristic verve when he was only fifteen, Remington took stock as follows: I don’t amount to anything in particular. I can spoil an immense amount of good grub at any time in the day. … I go a good man on muscle. My hair is short and stiff, and I am about five feet eight inches and weigh one hundred and eighty pounds. There is nothing poetical about me.

The reference to spoiling good grub was prophetic. Over the years Remington’s weight swelled alarmingly, and he waged a ceaseless, futile war against corpulence until at last the proud athlete was encased in a prison of flesh. But in 1878 he was every inch a young man in his physical prime.

Remington’s year and a half at Yale exposed him to formal instruction in the principles and elements of art and to studio courses in drawing and perspective. The consensus is that he profited little from the experience and seemed to enjoy Yale in direct proportion to the number of hours he spent on the football field instead of in the classroom. He was a first-string forward, or rusher, on the 1879 team that included among its halfbacks Walter C. Camp, the legendary “Father of Football.” Perhaps football became Remington’s substitute for soldiering. It was Stephen Crane who in 1900 would write about his classic novel of men at war, The Red Radge of Courage , that he had “never smelled even the powder of a sham battle” but had got his “sense of the rage of conflict on the football field.” Football in Remington’s time was a brutally physical contest played with only minimal padding and protection, and he gloried in its bloodier aspects. Years

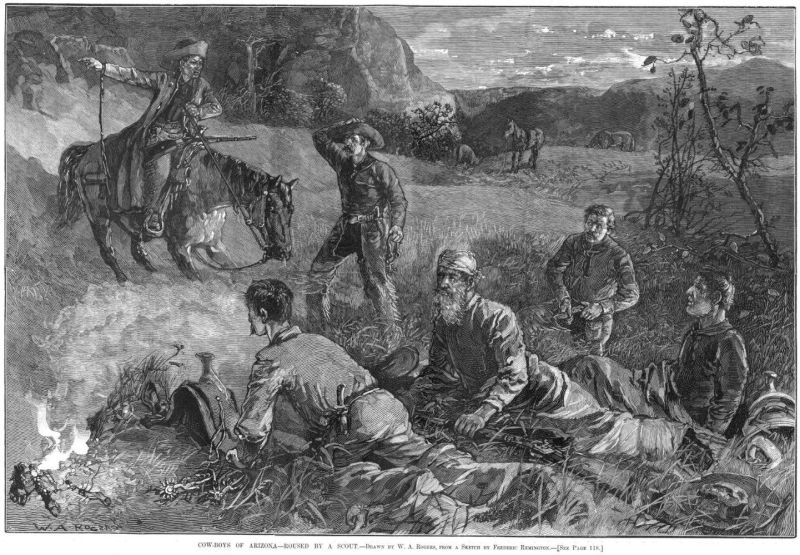

Remington’s studies terminated abruptly upon the death of his father in February, 1880. He chose to drop out of Yale, and after dabbling with a clerkship or two in Albany, fighting off boredom by boxing and horseback riding, and probably squandering a small advance on his patrimony, he at last resolved to satisfy an old ambition by going west. He left for Montana in August, 1881, “to make a trial of life on a ranche,” the local paper reported, though biographers have speculated that his real motive may have been disappointment in love. Two years earlier Remington had met and begun courting the one girl, Eva Caten, who in all his life could distract him from his exclusively masculine pursuits. He got as far as asking her father’s permission for her hand in marriage, but his suit was spurned for the excellent reason that he had no prospects and no particular ambition in life. Whatever his motives were in going to Montana, Remington did not stay long, perhaps two and a half months at the outside. But he had got his taste of the West, sketched some of what he had seen, and even enjoyed a small but real triumph as an artist when Harper’s Weekly for February 25, 1882, published a redrawn version of one of his efforts under the title “Cow-boys of Arizona.”

At this juncture in his life, however, Remington was less concerned with establishing himself as an artist than freeing himself from his desk in Albany and getting back west again. The opportunity came in the fall of 1882, when, upon turning twenty-one, he received the bulk of his inheritance, some nine thousand dollars, which he at once proceeded to spend with a free hand. Then in late February, 1883, acting upon the advice of a former Yale classmate, he plunged what was left into a quarter-section sheep ranch about ten miles south of Peabody, Kansas. It was not cattle ranching, and it was certainly not the frontier; but it was a chance to live in the West and become in fact a Westerner.

Remington stuck with sheep ranching for about a year, doubling his spread and passing his time with a set of like-minded young bachelors who appear to have been most adept at fun. One caper, however, ended unamusingly. It took place on Christmas

The precise effects of the sheep venture on Remington’s artistic development are difficult to assess. Throughout the year he had continued drawing, and if he learned little about the workaday realities of running a sheep ranch and less about financial responsibility, he had profited in other ways. The year on the ranch was to be his longest continuous residence in the rural West, and while the area around Peabody could hardly be called wild, vestiges of its frontier past remained in the early i88o’s. The country had impressed Remington, and his imagination was active enough to provide the missing element of hair-raising adventure. Shortly after arriving in sedate Peabody he scribbled the following to a friend in Canton: “Papers came all right—are the cheese—man just shot down the street—must go.” That the Peabody newspapers of the period record no shooting incident is not surprising. The West had won Remington over, and he had begun the process of making it conform to his impression of what it should be like. If Kansas had failed to live up to his expectations, it had still offered him room to be young and feel a glorious sense of freedom galloping across the prairie at dawn, his mare’s stride “steel springs under me as she swept along, brushing the dew from the grass of the range. …”

Such carefree times must end for all, but Remington did better than most at resisting the inevitable. His move to Kansas City was followed by a trip east, and on September 3o, 1884, he married Eva Caten. Just what in his activities over the past four years had convinced Mr. Caten that Remington would now make an acceptable son-in-law remains a mystery. The new bride and groom left at once for Kansas City to set up house. The details of this period of their life are sparse, perhaps because Eva, after only a few months away from friends and family, decided that the West—even the urban West—was not for her and returned home. Evidently there were other considerations, too. What Remington had made from the sale of his sheep ranch he had invested in

With Eva’s departure Remington was on his own again, and he spent the next few months wandering across the desert Southwest, sketching what he saw and filling his portfolio. At the end of summer he rejoined Eva in New York and thereafter accepted the fact that they would never live out west again. Instead he would periodically return on his own, often on assignment once he had become an established illustrator. His trips were far-ranging and included visits to the Canadian plains and Mexico. Some lasted for a month or more. But it was an arrangement that the Remingtons were able to accommodate themselves to throughout their marriage.

The winter of 1885-86 was a lean and trying one for the young couple. They had moved into a small apartment in Brooklyn in order to be nearer the market for magazine illustrations. Two of Remington’s sketches had been redrawn and published in Harper’s Weekly , but it was not until January 9, 1886, that he finally appeared on the cover under his own name. Appropriately, the subject was “Indian Scouts on Geronimo’s Trail” and featured a soldier on horseback, his head turned away scanning the distance for signs of hostiles. He is accompanied by four Indians jogging along at his side and what appears to be a Mexican scout trailing behind. The officer cuts a dashing figure with his hat set at a rakish angle, framing the strong lines of his pro- file. The Indian scouts, in comparison, are small, rather scrawny men, wild-looking but unimpressive. The picture exhibits all the faults of Remington’s early work—the composition cluttered and lacking focus, the figures weakly drawn and somewhat out of proportion, and the perspective unsure. Some of these difficulties could be attributed to the engraver, but on the whole they typified Remington’s paintings at this time. He had an arresting subject, and it bore an air of authenticity. But he yet had much to learn about his craft. Bowing to necessity, he enrolled in the Art Students League and began attending classes in March, 1886. But his impatience with formal instruction won out, and by June he was off to follow in Geronimo’s tracks once again and acquaint himself further with the

The year and a half at Yale and the few months at the Art Students League comprised all the formal training Remington ever got, though the astonishing growth in his technical competence over the next few years, and indeed throughout his whole career, indicates that he was always willing to learn and improve. By the end of 1886 his work had already gained considerable sophistication and was beginning to appear with some frequency not only in Harper’s Weekly but in other magazines as well. Remington’s breakthrough into regular illustrating came late in that year when Poultney Bigelow, owner and editor of Outing magazine, bought his portfolio of western sketches and thereafter kept him busy with a slew of commissions. Recalling his introduction to Remington’s art, Bigelow remembered himself bent over his desk one day, tired from overwork and in no mood to be disturbed. Suddenly a portfolio of drawings was shoved into his hand, and without looking up he gave them a quick glance. It was, he wrote, like receiving an “electric shock.” Instantly perceiving in these rough drawings a vitality and mastery of the subject matter that technical deficiencies could not conceal, Bigelow now for the first time looked up at the artist and recognized his former Yale classmate, Fred Remington. It is a fine tale, though perhaps a touch apocryphal; one suspects in it more the workings of the “old-boy” system than pure coincidence. At any rate, Outing marked a turning point in Remington’s career. The demand for his work was beginning to equal his ability to produce, and commissions were streaming in from some of the most prestigious magazines of the day. Besides Harper’s Weekly and Outing, St. Nicholas, Youth’s Companion, Century, Scribner’s, and Harper’s Monthly all carried his work by 1890.

Remington had arrived. Thereafter his career as an illustrator constitutes an unbroken tale of popularity and rising income, of moves into increasingly elaborate quarters at more impressive addresses, of a social set that included the rich and powerful—in short, of dramatic, overwhelming success. It is a tale, moreover, that cannot be understood without reference to the times in which Remington was working.

Americans by the iSgo’s had become uncomfortably aware of the magnitude of change that had overtaken the country since the Civil War. The social consequences of industrial growth and urban sprawl were being felt in the midst of a depression. For all the complacency and confidence that a firm faith in progress bred, unrest had manifested itself in an agrarian protest movement that promised to exert a decided impact on the national political scene, in labor agitation in the cities, and in a mounting fear of the so-called new immigration from southern Europe, which threatened to swamp the American melting pot with “undesirable” elements. In conjunction with these worries Americans were also becoming aware of the fact

Pre-eminent among those recognized as authorities on the West in the iSgo’s were, besides Remington, two writers—Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister. Together they formed a trio of Easterners of good background who had journeyed to the territories for different personal reasons and had been on hand to witness, as Remington remarked, “the living, breathing end of three American centuries of smoke and dust and sweat.” Acquainted with one another privately, they exchanged letters, encouragement, and compliments; publicly they formed an exclusive mutual-admiration society given to endorsing one another’s western products. Nor did they do anything to discourage the popular impression that they not only knew the “real West” but were among its few legitimate interpreters. They acknowledged Francis Parkman as a mentor of sorts but otherwise kept the ranks tightly closed. Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, it would seem, harbored the sum total of the nation’s expertise on things western.

Remington first came into contact with Roosevelt as illustrator for a series of somewhat sentimentalized articles on ranch life in the Dakota Territory that ran in Century magazine in 1888. It was an important commission for Remington at the time, establishing his reputation as the delineator of the cowboy, and he and Roosevelt subsequently kept in touch. “It seems to me that you in your line, and Wister in his, are doing the best work in America today,” Roosevelt observed in a letter in 1895; and two years later he added: “You know you are one of the men who tend to keep alive my hope in America.”

It was also as illustrator that Remington originally became acquainted with Owen Wister. The two met for the first time in Yellowstone Park in September, 1893. and formed an attachment based on mutual interests, mutual prejudices, and the shared conviction Jiat the country in 1893 was going to the dogs and needed a strong infusion of oldfashioned patriotism if it was to be saved. They also saw the possibility of rewarding collaboration, writer and artist, and so quickly did their friendship develop that a year later Eva could tell Wister that he was “one of the few men” her husband “loved” and could not “see too much of.” Though Remington and Wister did

Remington even had the high satisfaction of receiving an accolade from the old master himself, Francis Parkman, when he was commissioned at Parkman’s request as one who “knew the prairies and the mountains before irresistible commonplace had subdued them” to illustrate the 1892 commemorative edition of The Oregon Trail . It was a gratifying commission, equivalent to a laying on of hands. The next year Parkman was dead, and Remington along with Roosevelt and Wister stood unrivalled among contemporary interpreters of the vanished West. Julian Ralph, writing in Harper’s Weekly in 1895, expressed a common opinion when he observed: We almost forget that we did not always know the little army of rough riders of the plains, the sturdy lumbermen of the forests, the half-breed canoeman, the dare-devil scouts, the be-fringed and be-feathered red man; and all the rest of Remingtoniana that must be collected some day to feast the eye, as Parkman and Roosevelt and Wister satisfy the mind.

The West belonged to these men; it was, for the vast American public, what they said it was or in Remington’s case what he showed it to be. “It is a fact that admits of no question,” one astute critic commented in 1892, “that Eastern people have formed their conceptions of what the FarWestern life is like, more from what they have seen in Mr. Remington’s pictures than from any other source, and if they went to the West or to Mexico they would expect to see men and places looking exactly as Mr. Remington has drawn them.”

Remington’s vision of the West as a man’s domain, providing at once challenge and fulfillment, is perfectly consonant with his lifestyle and his personal philosophy. He was not profound or subtle, but given to a code of values right out of Roosevelt’s “strenuous-life” ethic—politically conservative, frequently racist, always superpatriotic, and convinced that, as Roosevelt said, “it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness.”

Critic Harold McCracken has argued for a depth and complexity to Remington inherent

But these opposite lifestyles did not betoken some internal contradiction warring within Remington. Rather they were perfectly consistent with the values shared by a number of upper-class Easterners in this same period who, almost as if taking their cue from Roosevelt, sought out personal challenges, whether on western ranches, hunting and camping trips in the north woods ("to suffer like an anchorite is always a part of the sportsman’s programme,” Remington observed), the football fields of Yale and Harvard, or the battlefields of Cuba. This cult of “stress seeking” affirmed the need for a man to constantly test himself, pushing himself to the limits of courage and endurance and in so doing preserving intact those vital pioneering traits that had made America great but were now in danger of withering away before the sheer ease of modern life. “I believe that a man should for one month of the year live on the roots of the grass, in order to understand for the eleven following that so-called necessities are luxuries in reality,” Remington declared in 1894, in reference to his own experiences in the Sierra Madrés. Among the stress seekers there was an obsession with the pitfalls of wealth and worldly success, for they led directly to what might be an irreversible softening of the national fiber. Roosevelt railed at the “moneyed and semi-cultivated classes, especially of the Northeast” for producing a “flabby, timid type of character which eats away the great fighting qualities of our race.” The martial virtues were essential to the country’s well-being, and they must not be permitted to atrophy. Noblesse oblige dictated that the upper classes, who were most culpable anyway, should provide leadership in the campaign to preserve the best in the American character.

At times the stress-seeking philosophy degenerated into chest thumping and saber rattling. Its adherents suspiciously surveyed the world from the embattled perspective of “survival of the fittest” and tended to a deeply pessimistic view of current events. For Remington it added up to an agreeable intellectual milieu. He was not a subtle man. Direct statement was his style in the iSgo’s, and he was a walking catalogue of the prejudices of his time and class. He despised labor protesters and strikers as un-American “rats” and fretted over the inconvenience he might be caused by a

As an immensely popular illustrator driven “crazy with work” Remington had to keep a strict regimen. He was usually up by six each morning and, after an ample breakfast, at his easel by eight. He painted until mid-afternoon, then relaxed by walking, riding, cycling, or paddling, depending on the circumstances. Prolific and busy as he was, Remington treasured all the more his respites from “the sad effeminacy of the studio"—respites spent among the “hard-sided” cavalrymen and the other frontier types he admired. He wholeheartedly identified with the men he met out west, yet largely avoided the self-conscious need to emulate them in dress and manner. He was outgoing and accessible—”a good natured smooth faced fat blonde original good fellow,” according to one officer who met him in 1890. Remington was, one hunting partner recalled, “an admirable companion, with an inexhaustible fund of adventure and anecdote.” It was as a companion—a man with whom one drank and pleasantly passed the leisure hours—rather than as a friend that he was ordinarily remembered.

Some biographers have wanted to make of Remington a veritable Odysseus, wandering the West from point to point, crisscrossing its vast expanse, soaking up its every detail until at last he knew it, knew it all, and knew it intimately. He knew (they say) the cowboy, the miner, the army officer, the enlisted man, the Indian scout, the homesteader, the sheepherder, the mountain man—everyone, apparently, but the schoolmarm and the honky-tonk girl. He knew the wild Indian, too—each and every tribe—as well as the Mexican vaquero and the Northwest Mounted Policeman. He knew

There seems to be a desire at work here to make the irtist’s life as exciting as the scenes he painted by implying that he personally witnessed most of what he subsequently depicted. The truth was something else. Perhaps the difficulty lies in assessing the limits of Remington’s actual experiences. In his own writing—and he was a frequent contributor of essays based on firsthand observations, as well as a short-story writer and a two-time novelist —Remington was scrupulously honest about what he saw and did as distinguished from what he had heard about. When his reports on his personal doings out west are stripped of their embellishments and reduced to a skeleton record of what actually happened to him, much of the romantic moonshine is dispelled at once. The cavalry patrols he rode with, for example, rarely saw, let alone exchanged fire with, hostile Indians. Instead they spent gruelling days traversing country that was often exhausting for men and horses, abiding climatic conditions as varied as the bone-chilling cold of a Dakota winter (”cold enough to satisfy a walrus,” Remington wrote) and the blazing heat of an Arizona summer with the thermometer stuck at 125 degrees. His experiences were on the whole perfectly ordinary. He soaked in his own sweat, choked on the dust, suffered the stiffness of breaking into the saddle again, and wondered what on earth he was doing exposing himself to such discomfort. Of course he loved it all, particularly the discomfort, and he reported accurately on what he had experienced.

But Remington was an illustrator for others as well, and he was, moreover, an artist. His personal experiences were steppingstones to imaginative re-creations; what mattered was not whether he had lived a particular episode, but how it fitted into his conception of the Wild West. It was Remington’s peculiar genius to be able to encounter reality, respond to it on a direct, reportorial level, and yet not be overwhelmed by it. Beneath the gritty surface of the western life that he pictured, Remington detected some magic impulse at work, and he cut through the monotony and boredom, the loneliness and isolation, the grinding dreariness of changeless days, to reveal a great, ongoing adventure, awesome in its sweeping power, the fulfillment of his every boyhood dream and, as his dramatic rise to popularity would indicate, the dreams of countless other Americans as well. The Wild West was Remington’s forte. He knew instinctively what would

Remington’s West is not a landscape artist’s paradise. His major oils, viewed with detachment, are remarkably unspecific and unspectacular in terms of setting. For him the West has been reduced to twin bands of powder blue sky and yellow ocher land, a timeless backdrop against which he played out his fantasies of pounding action. He loved the theme of pursuit and flight, of men charging head-on at the viewer while whooping Indians follow on their heels. In The Flight a solitary cowboy is shown in what seems a hopeless race for life. Though his situation is grim and his chances for survival slight, he stares straight ahead, determined to make the best of it. He is, by Remington’s standards, the model of masculine Americanism, a heroic ideal in a land where “life is reduced to its elemental conditions” (as Roosevelt wrote), a struggle for survival. The flight was prelude to another favorite Remington theme, the desperate stand. It could be cowboys, soldiers, or free trappers, it mattered little: they were united in a common cause, a life-or-death defense against superior numbers. Remington preferred to leave the attackers, usually Indians, to the viewer’s imagination. His concern was with the men at bay and the cool, efficient manner in which they comported themselves despite the grave peril they faced. One of his most striking variations on this theme was a splendid oil done in 1905 showing a Crow warrior “ridden down” by a band of Sioux. He stands high on a bluff, war club in hand, a figure of perfect stoicism, prepared to meet death without fear or complaint. No chance of escape remains to him, for his pony is exhausted, glistening with sweat, and the pursuing Sioux are closing in for the kill. The land is pitiless, stripped bare of even a trace of vegetation that could provide some shelter or a place to hide. It is not really the country of the Sioux or the Crow, of course; it is simply Frederic Remington’s favorite arena for violent action, the Wild West.

Recently Remington has received attention chiefly for his contribution to the romantic myth of the American cowboy. He, along with his friends Roosevelt and Wister, helped transform the working cowboy into a cultural hero, “as hardy and self-reliant as any man who ever breathed,” according to Roosevelt, “a slim young giant, more beautiful than pictures,” to borrow Wister’s description of that hero of a million daydreams, the Virginian. Remington’s illustrative work for both authors constituted his most direct contribution to the same heroic image. His very first appearance in Harper’s Weekly involved a cowboy subject, and his popular first bronze, done in 1895, was called The Bronco Buster . Cowboys were to him, Remington acknowledged, what “gems and porcelains are to others.” But it was not as the depictor of the cowboy that Remington stands supreme; his contemporary Charles M. Russell

Remington rarely harked back in his work to some earlier, idvllic time “when the land was God’s,” as Charlie Russell would say, and the world was full of a gentle wonder and mystery. His West was ever the setting for clash and confrontation, and the struggle for mastery between red men and white was its most compelling theme. As a boy his head was full of fantasies of Indian fighting, and as a young man he had followed the trail of Geronimo and the Sioux Ghost Dancers. He never did see a real battle between Indians and soldiers, but he knew intuitively what it was all about. It was savagery and civilization pitted in a death struggle whose final outcome was a certainty but whose little skirmishes were the stuff of epic: miniatures of that larger testing that had molded a pioneering race of men. His vision of the Indian wars was compressed into one mammoth oil entitled, with purposeful vagueness, A Cavah-y Scrap. Completed in 1909, Remington’s last year of life, it is a full-blown summation of his theme, as cavalrymen and Indians galore charge across a Hat ocher plain under a sky of solid blue. It is also an oddly disconcerting painting. It is rigidly separated into three bands: the sky, the tangled mass of horses and men, and the ground. Onlyone fallen cavalryman in the left foreground, and one rearing horse and rider in the exact center, break this pattern. For such a stirring scene, full of figures in frenzied motion, the canvas is strangely placid to the eye. This impression is not merely a matter of composition and coloring, either. Remington seems to have intended a highly stylized effect: a master narrator in paint, he has left his story line here quite indeterminate. Are the troopers charging through a band of Indians? Are they pursuing Indians? Or are they being pursued? Since the troopers and the Indians appear to be galloping in two parallel lines across the canvas, from right to left, it is unclear what precisely is going on and, for that matter, who is winning. Remington apparently wanted it that way; his painting deals not with history but with myth. It is as structured and timeless as the ritual drama it depicts, the winning of the Wild West.

Remington recorded both sides in the clash between red and white, and some have praised him for his sensitive understanding of the American Indian. But Remington understood the Indian onlv in a strictly limited sense, as a curious visitor

Try as he might to bridge it, this gulf remained for Remington. With the exception of a few of his later oils his Indian paintings always exhibited an emotional distance. He was an unlikely choice, therefore, when he was commissioned to illustrate a sumptuous new edition of Longfellow’s Hiawatha in 1889. Though the paintings and pen and inks he executed were popular in their time, Remington was not in entire sympathy with his subject. His literal, realistic approach did little to enhance the rich, mystical

aura of Longfellow’s poem. Anyway, Remington never pretended to be able to draw women, and this put him at a decided disadvantage when it came to rendering that ephemeral vision of poetic loveliness, Minnehaha. Remington’s version was hard-faced, angular, shapeless, and forgettable. He was better when the subject at hand was an Indian warrior. His short article (1898) about Massai, a renegade Apache who “manifested himself like the dust storm or the morning mist—a shiver in the air, and gone,” was widely acclaimed. Theodore Roosevelt, for one, greatly admired it. “The whole account of that bronco Indian, atavistic down to his fire stick; a revival, in his stealthy, inconceivably lonely and bloodthirsty life, of a past so remote that the human being as we know him, was but partially differentiated from the brute, seems to me to deserve characterization by that excellent but much abused adjective, “ weird ,” he enthusiastically wrote Remington.

“Weird” was the right word, and such heady praise may have persuaded Remington to attempt a more elaborate treatment of the Indian mind. He did so

It was Remington who gave us the “boys in blue"—those straight, lean, square-jawed, clear-eyed, mustachioed soldiers, professionally going about their business, the nation’s business, of “Winning the West” without a flicker of fear or a moment of self-doubt. Bullets kicking up dirt in their faces cannot make them flinch. They know the meaning of stern duty. Mortally wounded and in the agonies of death, they have no second thoughts about the sacrifice they have made for cause and country. Captured and led off by implacable foes to tortures unimaginable in their fiendishness, they register not a trace of emotion. They are soldiers in Uncle Sam’s army, and for Remington that answered all. He idolized them. They were, he wrote (of the officers, of course), “a homogeneous class. … They have small waists, and their clothes fit them; they are punctilious; they respect forms, and always do the dignified and proper thing at the particular instant, and never display their individuality except on two occasions: one is the field of battle and the other is before breakfast.” They are the purest embodiments of a heroic ideal, one that Remington quite literally bestowed on the nation in the form of a vivid mental picture of the Indian-fighting army.

It is all there: Remington’s vision of the perfect life, shared with a group of like-minded regular “good fellows” and made all the zestier by its spartan nature, its appeal to something higher than money, and its potential for sudden action: It is never a late evening, such a one as this, it’s just a few stolen moments from the “demnition grind.” The last arrival may be a youngster just in from patrol, who explains that he just “cut the trail of forty or fifty Sioux five miles below, on the crossing of the White River"; and you may hear the bugle, and the bugle may blow quick and often, and if the bugle does mingle its notes with the howling of the blizzard, you will discover that the occasion is not one of merriment. But let us hope that it will not blow. In truth it was Remington’s fondest wish that just once while he was along, the bugle would blow, and the soldiers he idealized would ride into action, and he, at their side, would see it all. Cuba, it turned out, and not the Wild West, was to provide Remington’s induction into the mysteries of war, satisfying, he wrote, “a life of longing to see men do the greatest thing which men are called on to do": “The creation of things by men in time of peace is of every consequence, but it does not bring forth the tumultuous energy which accompanies the destruction of things by men in war. He who has not seen war only half comprehends the possibilities of his race. …” “Say old man,” he exulted in a letter to Owen Wister written in June, 1898, “there is bound to be a lovely scrap around Havana—a big murdering- sure—” The actual experience of serving as a

Remington had come to recognize his own strengths and limitations. Personal experience was not the fountain of his inspiration any more. He had long since internalized his direct impressions of the West and transformed them into something else. In a letter to his wife, written in 1900, he hinted at just how conscious he was of this fact. “Shall never come west again,” he insisted. “It is all brick buildings—derby hats and blue overhauls—it spoils my early illusions—and they are my capital.” Still, Remington’s art underwent marked changes over the years. Some of these can be attributed to greater technical proficiency as time and practice sharpened his skills. But they also reflected a maturing perception of what his work was all about. He began as an illustrator and his paintings, like his field sketches, were correspondingly literal and linear, full of exact details carefully rendered and sometimes unified only by the story they told. This direct approach gave way in the last decade of his life to a far more impressionistic style, whereby color was freely applied and freely stroked to achieve effects that were at once more subtle and more artistic. No longer did he bother to work from photographs. Detail and narrative line were now subordinated to feeling and mood. Movement was no longer as important as the effect of movement. Typical Remington Indian-fighting scenes were transformed by his newly vigorous brushwork. Indian Warfare, for example, is an astonishing tableau of brown men and horses swirling past an island of blue, the rhythm so perfectly maintained that it is like watching a moving carousel as the warriors attempt to rescue a fallen brave without allowing their ponies to

It was his nocturnals that most freed Remington from his public image as the supreme portrayer of raw action. Guns flash in some of his night scenes, but on the whole they are mood pieces. They contain an inbuilt suspense as jagged shadows sprawl across the moonlit landscape hiding unseen dangers. More than ever before Remington managed in these works to involve his viewers in the meaning of the Wild West. In the past he had always been able to imagine himself at the center of the action and had effectively conveyed this impression to his audience. Now the land had been tamed, denuded of the perils that once made it so fascinating. The dream was over, and darkness concealed the mundane that Remington could never abide, restoring to the Wild West its rightful aura of mystery and suspense by locating it in the one safe refuge that remained—the minds of Americans, in which Apaches might still materialize like ghosts beneath a starry sky. In his nocturnals he occasionally played with the dramatic effects of the firelight flickering across the canvas. But more often he worked with the subdued effects of moonlight, which turned lines into patches of luminescence and shadow and welded figures and landscape together. He favored two approaches: a light-colored horse or some other object in the foreground would serve as a source of light, emitting a ghostly glow in the darkness; or else a silhouetted figure would move across a landscape bathed in dim light and often snow-covered to heighten the effect. In Bell Mare the lead horse and the packs on the mules provide highlights, while the pale, alert face of the rider, floating above the animals, catches the tension of a night passage through hostile country. In Hungry Moon jadegreen figures of Indian women bend over the carcass of a buffalo, finishing the butchering that will mean food in the lean times ahead suggested by the snow blanketing the ground. Remington found himself so at home in these nocturnals that perhaps half of his paintings in his later years were night scenes. They won both critical and popular acceptance and thus helped Remington realize an old ambition that had eluded him in the past: recognition not only as an illustrator but as an artist as well. Back in 1893 and 1895 Remington had held exhibitions

In his quest for acceptance as a legitimate artist Remington had begun exhibiting at the National Academy of Design as early as 1887, and by 1899, the year he discontinued the practice, he had hung a total of thirteen paintings. He was made an associate member of the academy in 1891 but otherwise received no special recognition. Then in 1900 a virtually unknown Hoboken, New Jersey, artist, Charles Schreyvogel, entered an oil entitled My Bunkie in the academy’s exhibition and on only his second try walked away with the coveted Thomas B. Clarke prize for the “best American Figure Composition.” To say that this galled Remington is to state the case mildly. He regarded Schreyvogel’s depiction of a cavalry trooper rescuing his fallen buddy as “falsehood and fake” and formed an obsessive loathing for his quiet, sensitive rival. Remington could be encouraging and kind to young artists seeking his advice and criticism where their relative stations were clearly understood; but he did not like direct competition and regarded others suspiciously as predators on his private preserve. Thus he lay in wait for Schreyvogel, nursing his grudge. In 1902 he tried unsuccessfully to interest Wister in drafting “a statement which must be made which will stop dead the fools who are trying to confuse the public, by their ignorance, into thinking that they too understand.” No mention was made of Schreyvogel, but it was clearly whom Remington had in mind, for seven months later, in April, 1903, he attacked. The occasion was the unveiling of Schreyvogel’s latest historical oil, Custer’s Demand , which had received a long, flattering

To add salt to Remington’s wounds President Roosevelt publicly admired Custer’s Demand and had Schreyvogel to lunch that November. He told him, “What a fool my friend Remington made of himself, … he made a perfect jack of himself"—remarks that Schreyvogel relayed in a letter to his wife but instructed her not to repeat. (The letter was published a few years ago.) The Schreyvogel affair was, all told, a sorry episode in Remington’s career. It undoubtedly cost him a certain amount of respect, but the sting was eased by the fact that his own paintings were finding an increasingly favorable reception. In 1900 Yale had awarded him an honorary Bachelor of Fine Arts, and in 1903 he signed a contract granting Collier’s Weekly exclusive reproduction rights to twelve paintings of his choice each year for four years. In return he was to receive a flat rate of a thousand dollars a month, thus providing him financial security without the drawbacks and deadline pressures of illustrating. Equally gratifying was the fact that public and critics alike approved the new impressionistic direction his work was taking. Prints of his Collier’s paintings were in popular demand, and after his 1909 show at Knoedler’s, where he had been exhibiting each year since 1906, Remington could crow in his diary: “The art critics have all ‘come down'—I have received splendid notices from all the papers. They ungrudgingly give me a high place as a ‘mere painter.’ I have been on their trail a long while and they never surrendered while they had a leg to stand on. The ‘Illustrator’ phase has become a background.” One month later Remington was dead.

Rum and that lifelong fondness for “good grub” had played havoc with Yale’s starting forward, the companion in saddle of army officers, cowboys, and Indian scouts. His weight had risen slowly through the iSgo’s—he weighed 240 in 1897—and by the end he was pushing 300. He could no longer mount a horse or stoop over to pick up a tennis ball, and even walking had become an effort. His friend Augustus Thomas remembered: The waning of his great strength was a more sensitive subject with him than his increasing weight, which produced the condition. Gradually in our Sunday walks, the hills grew steeper for him. His favorite ruse for disguising the strain on him was to stop occasionally and survey the landscape: “Look there, Tommy, how that land lies. I could put a company of men back of that stone wall and hold it against a thousand until they flanked me.” As with the Southern gentleman who used to look out of the window after passing the decanter to his guest, it was the part of friendship on these occasions to multiply details of the suppositious fortifications until the commander regained his wind. Children regarded Remington’s “big bottom” with awe when he came to visit (”… how that man would eat,” a waitress at an Adirondacks hotel later remembered. “My, my, my, how that man would eat!"), and Eva bluntly referred to him as “my massive husband.” There is something a bit pathetic in all this; throughout his life Remington had subscribed, rather noisily, to a rigorous code of masculinity. Thus his bloated condition was not just a matter of eating and drinking too much, it was a matter of self-indulgence and softening. It was, in brief, the defeat of a personal ethic. At forty-seven Remington

His remaining days, as it turned out, were sadly few. Remington had complained of “belly aches” periodically in 1909, and a particularly severe one a few days before Christmas brought the doctors out to perform an emergency appendectomy. It was too late to save him—peritonitis had already fatally damaged his system—but he was cheerful and able to open presents on Christmas morning. The next day he was dead at forty-eight. During a professional career spanning less than a quarter of a century Remington had left behind nearly three thousand works of art, including pencil and pen sketches, pastels, water colors, oils, and bronzes, as well as two novels and five collections of stories and essays—almost all of them concerned with his commanding theme, the Wild West. At the end he had attained his personal summit, recognition by his contemporaries not only as a gifted illustrator but also as an accomplished artist. It was not, for Frederic Remington, a bad time to leave the scene.