Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 5

Personal charm and affability are traits not commonly associated with revolutionaries, and rarely has an agent of social upheaval been held in such universal esteem by his contemporaries as was Dr. Joseph Warren. He seems to have been a man nearly everyone liked, and his qualities come down to us in those dignified adjectives of the eighteenth century—gentle, noble, generous. So it is difficult to know if it was because of these characteristics or in spite of them that he was one of a handful of provincials most feared by British officialdom.

Not without reason, Lord Rawdon called Warren “the greatest incendiary in all America”; with the possible exception of Warren’s colleague and intimate, Samuel Adams, the Boston physician did more than any other American to maneuver the dispute between Britain and her colonies into a revolution. For some years he believed that change could be accomplished within the system (he felt obliged to do “every thing in my power to serve the united interest of Great Britain and her colonies”), but by 1774 he had concluded that little hope lay in that direction, so intransigent were George in and his ministers. His goals and his determination had hardened: as he wrote to John Adams, “… the mistress we court is Liberty , and it is better to die than not to obtain her.

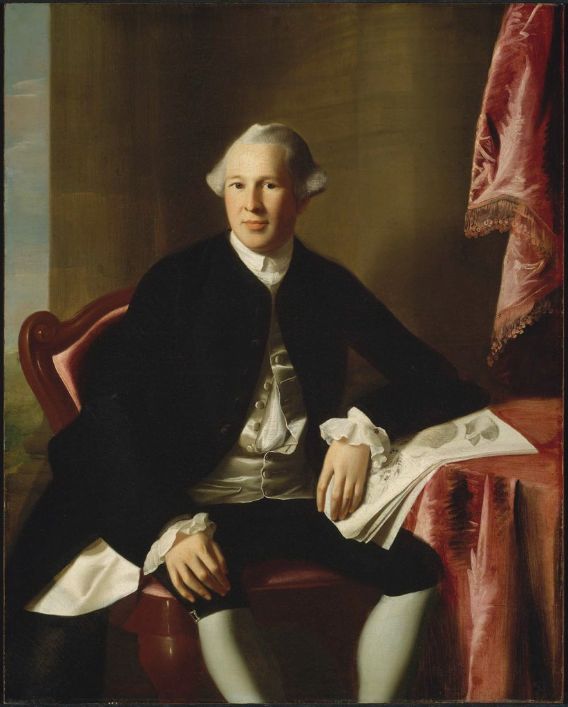

When John Singleton Copley painted his portrait in 1775, Warren was a fine-looking man of medium height, with large, wide-set eyes, full mouth, rather long, straight nose, and blond hair; although he was only thirty-four, there is in the fullness of the face and in his posture a hint that he was beginning to add a little weight. To look at the portrait is to accept the opinion of Warren’s contemporaries: that he was kind, friendly, entirely frank and open in all he said and did, scrupulously fair and humane in dealings with friend and enemy alike — a man universally trusted and admired. Born on a Roxbury farm in 1741, Joseph Warren made his way through Harvard, studied medicine with Dr. James Lloyd in Boston, and while still in his twenties was regarded as one of the town’s leading physicians. He was also known as a leader of the radical opposition, who was shaping public opinion in Boston against the Crown’s policies.

With Sam Adams, Warren initiated the Committees of Correspondence, which, as Governor Thomas Hutchinson wrote, brought Massachusetts from “a state of peace, order, and general contentment … into a state of contention, disorder, and general dissatisfaction.” He gave speeches, wrote articles, attended countless caucuses and meetings, petitioned and attacked the authorities, and was a dominant figure in the Boston Massacre trial and the Tea Party. A driving force in the Committee of Safety, he took the