Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 4

Authors: Stephen W. Sears

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 4

It would have taken considerable effort to locate an Allied fighting man on the battle line in Western Europe on September 10, 1944, who doubted that the end of the war was just around the corner. To American GI’S and British Tommies up front, heartened by six weeks of unrelieved victory, the chances of being home by Christmas were beginning to look very good indeed.

Those six weeks had been spectacular. Since late July, when the Anglo-American armies had burst out of their Normandy beachhead, the vaunted German army had fled for its life. Narrowly escaping encirclement at Falaise, nearly trapped against the Seine, harried out of Paris, driven pell-mell toward the Siegfried Line, which guarded the borders of the Third Reich itself, the German forces in France had lost a half million men and 2,200 tanks and self-propelled guns. It was a rout, a blitzkrieg in reverse.

The optimism buoying the combat troops was not entirely shared by the Allied High Command, however. Supplies were critically short, and the enemy showed signs of getting himself sorted out. A hot inter-Allied argument—soon to be christened the Great Argument - was raging over the next strategic step. On September 10 the debate hit one of its peaks. The setting was the Brussels airport, the scene the personal aircraft of the Supreme Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower. The principal debater was British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery.

The meeting went badly from the start. Eisenhower, who had recently wrenched his knee in a forced landing during an inspection flight to the front, was confined to his plane. On arriving, Montgomery arrogantly demanded that Ike’s administrative aide leave while his own stayed. Ever the patient conciliator, Eisenhower agreed. Montgomery then delivered himself of an increasingly violent attack on the Supreme Commander’s conduct of the war. Rather than continuing the advance on Germany on a broad front, Montgomery argued for a halt to all offensive operations except for “one really powerful and full-blooded thrust” in his own sector, aimed toward the great German industrial complex in the Ruhr Valley and beyond.

“He vehemently declared,” Eisenhower was later to write, “that … if we would support his 21st Army Group with all supply facilities available he would rush right on to Berlin and, he said, end the war.”

Eisenhower’s temper rose with Montgomery’s intemperance. Finally he leaned forward, put his hand on the Field Marshal’s

When he left the meeting, however, Montgomery carried with him Eisenhower’s approval of a plan code-named Operation Market-Garden. If he had gained less than he sought, Montgomery at least had in Market-Garden what British war correspondent Chester Wilmot has described as “the last, slender chance of ending the German war in 1944.”

In those early days of September the Allies had simply outrun their supply network. Armored units were stalled without gasoline. Replacements, food, ammunition, and spare parts were far below even minimum needs. Yet only by applying hard, continuous pressure on the enemy could the Allies hope to breach the Siegfried Line and win a bridgehead across the Rhine before winter—and perhaps even force a complete Nazi collapse.

Supply problems could not be solved overnight. The Allies had reached the German border 233 days ahead of their pre-invasion timetable, and it would take weeks for logistics to catch up. In Eisenhower’s view, just trying to reach the Rhine on the present supply shoestring was gamble enough. To approve Montgomery’s “full-blooded thrust” without a solid logistic base and without the capability of making diversionary attacks elsewhere on the front was to invite its destruction. Better to advance to the Rhine on a broad front, Ike believed, and then pause to regroup and resupply before plunging on into the Third Reich at full strength.

Ike conceded that the strategic opportunities in Montgomery’s northern sector were attractive — the vital Nazi arsenal of the Ruhr, the good “tank country” of the north German plain — and had granted supply priority to the 21st Army Group. Yet he was unwilling to rein in completely U.S. Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group to the south, whose advance was aimed at the industrialized Saar region.

The Supreme Commander also carried a burden of quite a different sort: mediating between two eccentrics of towering military reputation. On the one hand, spearheading Bradley’s army group, there was the flamboyant George

Then there was Bernard Montgomery, victor of El Alamein and Britain’s great hero, with an acrid manner and an insufferable ego that invariably grated on his American colleagues. To halt either Patton or Montgomery at the other’s expense might open a serious fissure in the Anglo-American coalition. Dwight Eisenhower was too good a student of coalition warfare to allow that to happen.

In any case the issues that September were clear: how to keep the pursuit from bogging down; how to break the barrier of the Siegfried Line; how to gain a bridgehead across the Rhine. Operation Market-Garden offered to resolve all three.

By September 10 the staging area for Market-Garden was secure. At dusk that day elements of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group crossed the Meuse-Escaut Canal in Belgium, close to the Dutch border. Most of Belgium was in Allied hands, including Antwerp, the great port so badly needed for logistic support of Eisenhower’s armies. Antwerp was useless, however, until German troops were routed from the banks of the Scheldt estuary that linked the port with the North Sea.

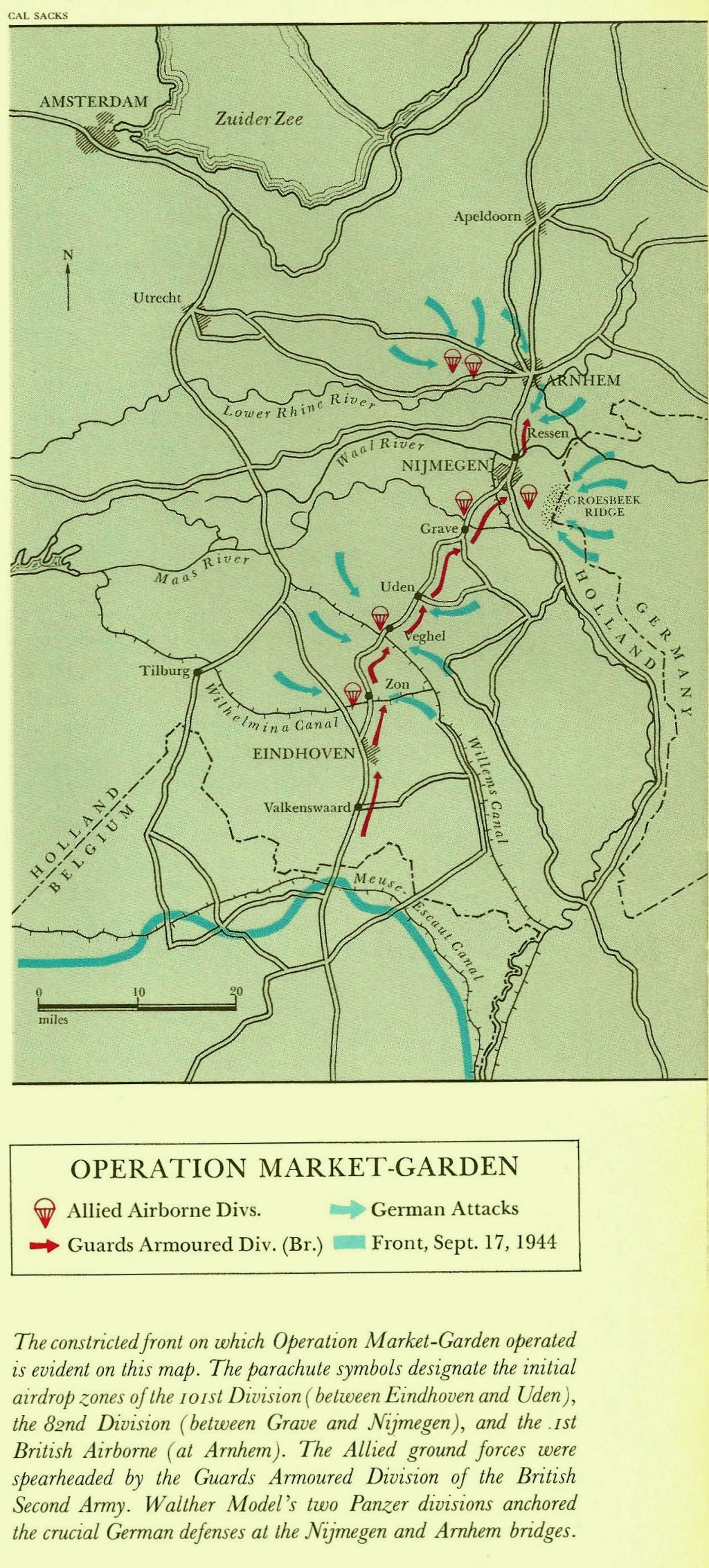

Operation Market-Garden, scheduled for September 17, involved a sudden, one hundred-mile thrust from the Meuse-Escaut Canal almost due north into Holland, crossing the Lower Rhine at the city of Arnhem and reaching all the way to the Zuider Zee. If successful, it would completely outflank the Siegfried Line and win a coveted Rhine bridgehead. In addition, it would cut Holland in two, trapping thousands of German troops and isolating the chief launching sites of the deadly v-2 ballistic missiles that were pummelling London.

With these objectives in hand Montgomery was confident that Eisenhower would have no choice but to fully support his plan to seize the Ruhr and drive on toward Berlin. Thus, the Field Marshal declared, the war could be won “reasonably quickly.”

Elsenhower was less sanguine. He cautioned Montgomery that the opening of Antwerp could not long be delayed. Much would depend on Market-Garden succeeding quickly and at minimum cost.

As bold as the plan itself was the technique designed to carry it out. The Dutch countryside was ideally suited to defense, marshy and heavily wooded and cut by numerous waterways: in the span of sixty-five miles the single highway running north from the Belgian border to Arnhem crossed no less than three canals, two small rivers,

Previous airborne operations had shown that the effectiveness of paratroops varied in inverse proportion to the time they had to hold their objectives; in a long fight they were invariably over-matched in firepower. On the face of it, then, laying down a carpet of paratroopers and glider-borne infantry up to sixty-five miles ahead of the ground forces, as Market-Garden proposed to do, was a very high-risk tactic. Eisenhower and Montgomery counted on the condition of the German forces in Holland to even the odds. Allied intelligence was confident that behind a thin crust of resistance along the Meuse-Escaut Canal, there was hardly any organized enemy at all.

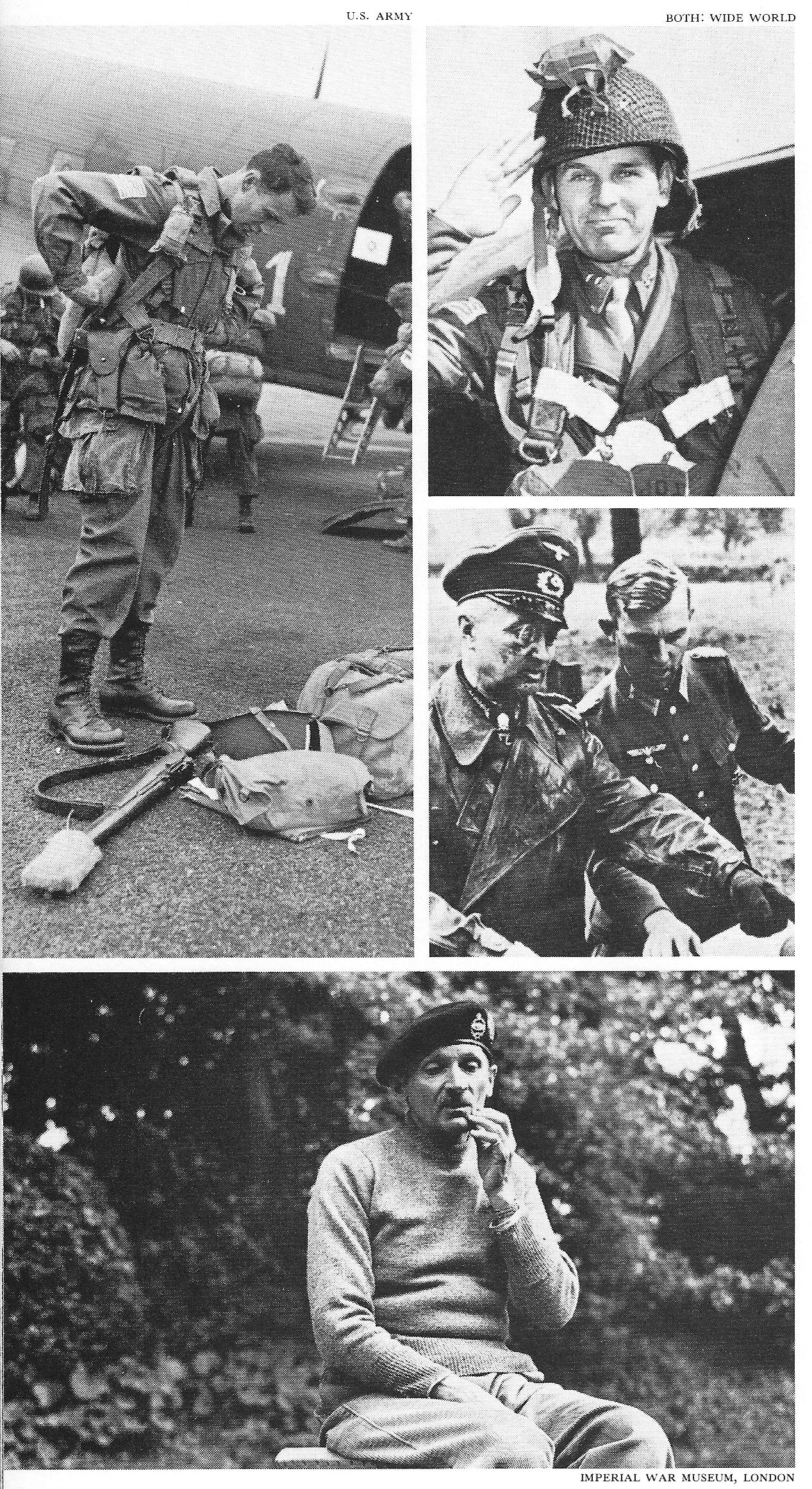

Opposing the Allies in this northern sector was Field Marshal Walther Model, working with his characteristic furious energy to patch together a defensive line. Model was a stocky, rough-hewn character, a favorite of Hitler’s who had performed well in crises on the Eastern Front and who liked to call himself “the Führer’s Fireman.” His command had been so badly shattered in France, however, that facing Montgomery in early September there was only a mixed bag of stragglers, garrison troops, and Luftwaffe ground units, braced by a few green paratroop regiments and some fanatical but inexperienced SS men. Line infantry and armor were in very short supply.

A few days before Market-Garden was scheduled to begin, fragmentary reports came in from the Dutch underground of two German armored formations that had just bivouacked north of Arnhem, apparently for refitting. Allied intelligence surmised that these must be the gth and i oth SS Panzer divisions. Both were known to have been decimated in the French debacle, and intelligence discounted them as a threat to the operation.

In England U.S. Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton’s First Allied Airborne Army, honed to a fine edge, was spoiling for a fight. The three divisions slated for Market-Garden—the U.S. Sand and ioist Airborne, veterans of the Normandy airdrop, and the ist British Airborne, which had fought in Sicily and Italy—had seen eighteen scheduled drops cancelled in a period of forty days as the ground forces advanced too fast to need them.

The mission of Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne was a drop near Eindhoven to seize that city and key river and canal bridges. Farther along the road to Arnhem would be James Gavin’s 82nd Airborne, assigned the big bridges over the Maas at Grave and over the Waal at Nijmegen, plus a ridge line to the east

In tactical command was British Lieutenant General Frederick Browning, dapper and brusque, the husband of novelist Daphne du Maurier. Browning had his reservations about the operation. Montgomery assured him he had to hold the Arnhem airhead only two days. “We can hold it for four,” Browning replied. “But I think we might be going a bridge too far.”

The ground forces, led by the Guards Armoured Division of the British Second Army, were to begin their northward push as the airdrop began. In command was Brian Horrocks, tall and white-haired and with something of the manner of a Biblical prophet about him. He had served Montgomery in North Africa and was both energetic and capable. Unlike Browning, Horrocks radiated optimism about the speed his forces would make. “You’ll be landing on top of our heads,” he warned the paratroops in mock seriousness.

Market-Garden lacked the “tidiness” — a substantial margin of superiority — that Montgomery usually demanded in an operation. There were few reserves in case of trouble and, with Patton embroiling the Third Army in battle to the south to keep his supplies coming, only minimum supporting stocks of gasoline and ammunition. Nevertheless, the plan was bold and imaginative; if the Germans were indeed on the brink of collapse, a victory at Arnhem just might provide the extra shove to keep the pursuit rolling and measurably shorten the war.

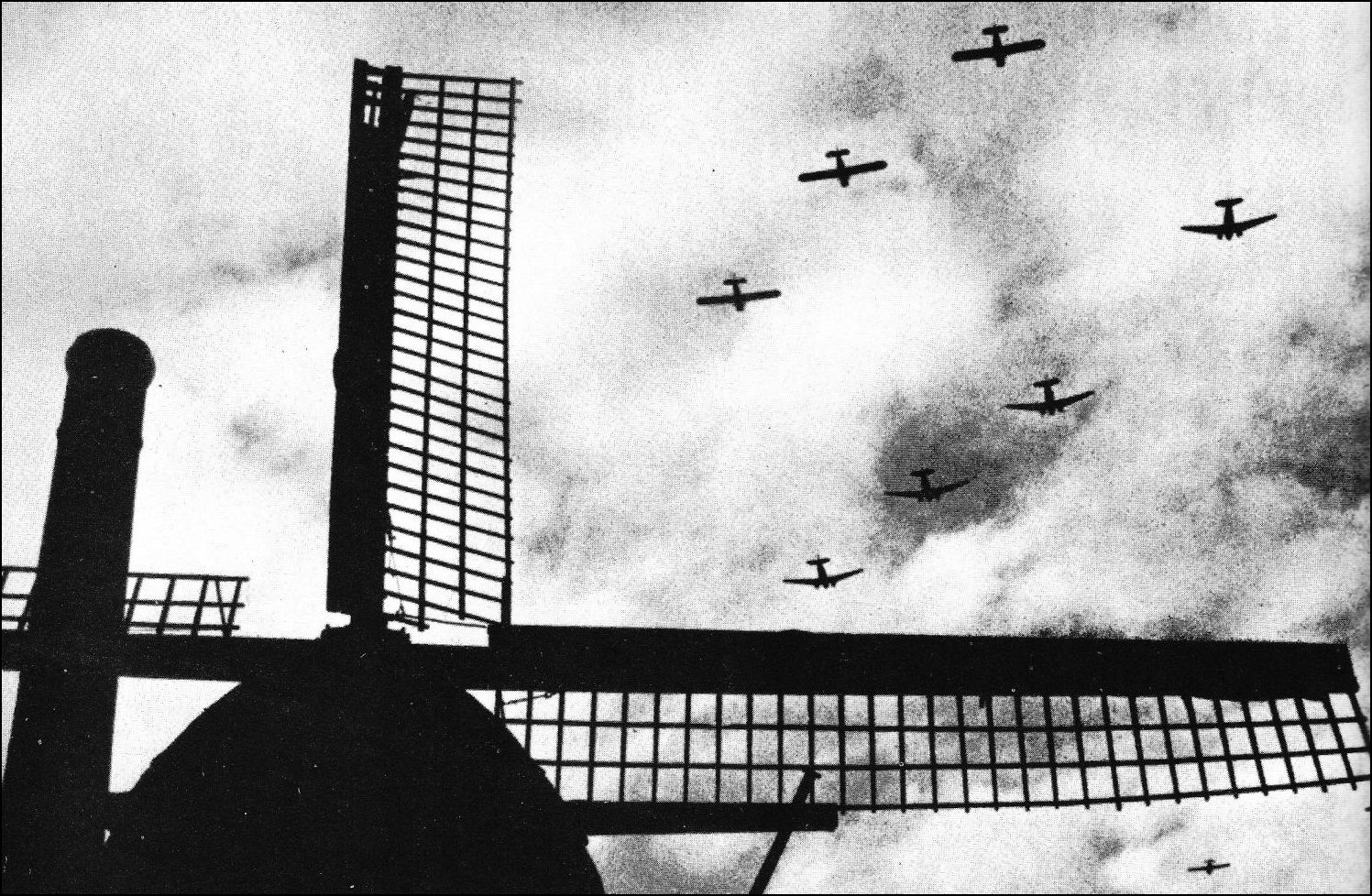

The opening phase of the largest airborne operation in history was, in the words of an RAF pilot, “a piece of cake.” D-day, September 17, 1944, was clear and windless, ideal for an airdrop. Shortly before 1 P.M. — following a softening-up of German defenses by 1,400 Allied bombers — some 1,400 transport planes and 425 gliders, plus swarms of escorting fighters, blackened the skies over Holland.

Edward R. Murrow had wangled a place in one of the 101st Airborne’s C-47’s to make a recording of his impressions for CBS Radio. “Now every man is out …,” Murrow reported. “I can see their chutes going down now … they’re dropping beside the little windmill near a church, hanging there, very gracefully, and seem to be completely relaxed, like nothing so much as khaki dolls hanging beneath green lampshades.… The whole sky is filled with parachutes.”

On the ground below, a few miles from the 101st’s drop zones, German General Kurt Student watched the sight with frank envy. Student was a pioneer of airborne warfare who had led the aerial assaults on Rotterdam and Crete. “How

Max Taylor’s 101st Airborne in the Eindhoven sector had been assigned the longest stretch of the Arnhem road — soon to be christened Hell’s Highway. Meeting little opposition, Taylor’s units formed up and seized their objectives one after another. However, as they approached the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal at Zon, a few miles north of Eindhoven, they were pinned down by the accurate fire of a pair of German 88-mm guns in a nearby forest. The 88’s were finally destroyed by bazooka fire, but the delay was costly. As the paratroopers tried to rush the Zon bridge, it was blown up in their faces.

Farther up Hell’s Highway Jim Gavin’s 82nd Airborne was also finding both success and frustration. The 82nd’s assault on the long, nine-span bridge over the Maas River at Grave was the most neatly executed strike of the day. Paratroopers landed close to both ends of the bridge. Using irrigation ditches as cover from the fire of a flak tower guarding the bridge, Gavin’s men worked their way to within bazooka range. Two rounds silenced the flak tower, and they rushed the bridge and cut the demolition wires. A second key bridge, over the Maas-Waal Canal, was taken in much the same manner. Gavin’s two regiments that dropped astride the dominating heights of Groesbeek Ridge southeast of Nijmegen dug themselves in securely on the wooded slopes.

The frustration came at 8 P.M. when, with the division’s three primary objectives in the bag, a battalion of the 508th Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Shields Warren made a dash into Nijmegen to try for the big highway bridge across the Waal. It ran head-on into a newly arrived battalion of the 9th SS Panzer Division. There was a sharp clash in the growing darkness. Warren’s men gained the building housing the controls for the demolition charges on the bridge, but the superior firepower of the Panzers drove them away from the span itself.

The Red Devils of the 1st British Airborne executed an almost perfect drop at Arnhem on D-day. It was here, however, that a serious tactical error on the part of Market-Garden’s planners caught up with them. The drop zones were six to eight miles west of the city. The need to hold the drop zones for later reinforcements — there were too few aircraft to deliver the full strength of any of the divisions in the D-day lift — meant that General Urquhart could spare but a single battalion to go after the bridge in Arnhem.

That evening five hundred men under Colonel John Frost slipped into the city along an unguarded road and seized the north end of the bridge. At

All in all, the airborne situation at the end of D-day was reasonably satisfactory. Montgomery’s red carpet was twenty thousand men strong. The landings had been unexpectedly easy, the easiest in fact that any of the divisions had ever made, in combat or in training. Except for the blown bridge at Zon and the failure of Gavin’s coup de main at the Nijmegen bridge, all objectives had been taken or, as at Arnhem, at least denied to the enemy.

The progress of the ground forces was less satisfactory, for the German crust beyond the Meuse-Escaut Canal was thicker and tougher than Allied intelligence had predicted. General Horrocks was forced by the marshy terrain to attack on the narrowest of fronts — the forty-foot width of Hell’s Highway. His armor was immediately in trouble. Concealed antitank guns knocked out eight of the Guards Armoured’s tanks in rapid succession. Infantry finally flushed the enemy from the woods on the flanks, but it was slow work.

Supported by rocket-firing Typhoon fighter bombers, the Guards battered their way forward, greeted in every village by the cheering Dutch. Portraits of Princess Juliana appeared magically in shop windows. But by nightfall the armored column was still a half dozen miles short of Eindhoven and a linkup with the 101st Airborne.

Heavy rain fell during the night, and in the morning of D-day plus 1 — Monday, September 18 — there were thick clouds over the Continent and fog over the Allied airfields in England, delaying the second day’s lift of glider infantry and supplies. By noon the 101st’s paratroopers had liberated Eindhoven, but not until seven that evening did the Guards Armoured link up with them. British engineers went to work building a prefabricated Bailey bridge to replace the blown canal bridge at Zon.

Model and Student began to put in counterattacks. Soon the two American divisions were embroiled in what Max Taylor characterized as “Indian fighting.” The fourteen thousand U.S. paratroopers had to control over forty miles of Hell’s Highway, which meant a constant scurrying from one threatened sector to another. An example was the fight for the big bridge at Nijmegen. This span was fast becoming the key to the whole Market-Garden operation, and both sides knew it.

The bridge across the Waal in Nijmegen was well over a mile long, with a high, arching center span. Five streets cut through a heavily built-up section of the city to converge on a traffic circle near the bridge’s southern entrance. Between the traffic circle and the bridge was a large wooded common known as Hunner Park, where elements of the

Just after dawn 82nd Division paratroopers deployed for their second attack on the bridge. The heavy-caliber German fire quickly drove them from the streets. Advancing through alleys and from doorway to doorway, the Americans worked their way to within a block of the traffic circle. That was as far as they got: reinforcements slated for the bridge attack had to turn back to meet a German thrust threatening to overrun the landing zones south of the city where gliders carrying Gavin’s artillery battalions were scheduled to land at any minute. The thrust was beaten off and the gliders landed safely — but the Nijmegen bridge remained in German hands.

A planned night attack on Hunner Park was cancelled by General Browning, who was disturbed by reports of a German buildup in front of Groesbeek Ridge to the southeast. If the Germans ever drove the thin line of paratroopers from the ridge, their guns would control both the Maas and Waal bridges, ending any chance of Market-Garden’s success.

Colonel Frost’s British troopers continued to cling to the north end of the Arnhem bridge, but the enemy repulsed every effort to reinforce the tiny bridgehead. The rest of the Red Devils were besieged at their landing zones west of the city. Communications had completely broken down. The first news from Arnhem was a clandestine telephone call placed by the Dutch underground. Recorded in an 82nd Division intelligence journal, the message was brief and blunt: “Dutch report Germans winning over British at Arnhem.”

The chief topic of conversation on the third day of battle, Tuesday, September 19, was the weather. A glider pilot complained of fog so thick that he could see “only three feet of towrope” in front of him. Less than two thirds of the reinforcements and supplies due the 101st arrived, and only a quarter of the 82nd’s. A resupply effort at Arnhem was a disaster. Model’s troops had finally driven the Red Devils from the drop zones, and a glider pilot on the ground watched in anguish as the C-47s came in and the flak caught them. “They were so helpless! I have never seen anything to illustrate the word ‘helpless’ more horribly,” he recalled. Over 90 per cent of the parachuted supplies fell into enemy hands.

As viewed by a Red Devil in the rear ranks, the situation at Arnhem “was a bloody shambles.” The bad weather scrubbed the scheduled drop of the Polish brigade at the south end of the bridge. Every

Guards Armoured tanks made good progress during the day, jumping off from the new Bailey bridge at Zon at dawn, linking up with Gavin’s 82nd Airborne, and reaching the outskirts of Nijmegen by early afternoon. Horrocks met with Gavin and Browning to work out a combined assault on the Nijmegen bridge. Time was a critical factor: the ground forces were now more than thirty-three hours behind the operation’s schedule.

The third attack on the Nijmegen bridge jumped off at 3 P.M. Gavin could spare only a battalion from his hardpressed forces on Groesbeek Ridge. The British contributed an infantry company and a tank battalion. A smaller force of paratroopers and tanks moved against a railroad bridge downstream.

This latter column fought its way through Nijmegen’s streets to within five hundred yards of the railroad bridge before it was halted by heavy enemy fire. Every effort to advance farther was stymied, and when an 88 knocked out one of the British tanks, the attackers withdrew.

Meanwhile, the battle for Hunner Park guarding the highway bridge reached its crescendo. Horrocks’ tanks had little maneuvering room in the narrow streets, and four of them were set ablaze by antitank fire. The German gunners kept the foot soldiers pinned down. In desperation, paratroopers attempted to advance along rooftops and through buildings, knocking out the connecting walls with explosives. But the enemy fire was too heavy and too well directed. As darkness fell, the third assault on the Nijmegen bridge sputtered out.

News from the loist’s sector to the south was ominous. Student was moving up powerful forces to try to cut Hell’s Highway behind Horrocks’ armored spearhead. In the late afternoon a squadron of Panther tanks broke through to the road and shot up a British truck convoy. General Taylor himself led a pickup force against the interlopers, and with their single antitank gun they knocked out two Panthers and drove off the rest.

That night the Luftwaffe made a devastating raid on Allied-held Eindhoven. “Half a dozen trucks carrying shells were hit directly,” reported war correspondent Alan Moorehead, “and at once the shells were detonated and began to add a spasmodic stream of horizontal fire to the bombs which were now falling at a steady rhythm every minute. Presently a number of petrol lorries took fire as well. … In the morning one saw with wonder how much of bright Eindhoven was in ruins …”

On Wednesday, September 20, the Market-Garden planners expected the Second Army’s tanks to be rolling toward the Zuider Zee. Instead they were stymied at Nijmegen.

Gavin’s plan was to force a crossing a mile downstream from the railroad bridge and take the defenders of both the railroad and highway bridges in the rear. A battalion of paratroopers of the 504th Regiment, commanded by Major Julian A. Cook, was picked to make the crossing. In concert with the amphibious attack, Gavin and Horrocks would hurl every man and tank they could lay their hands on against the southern approach to the highway bridge. H-hour was set for 3 P.M.

As the U.S. Army’s official historian phrased it,”… an assault crossing of the Waal would have been fraught with difficulties even had it not been so hastily contrived.” At this point the Waal is four hundred yards wide, with a swift, ten-mile-an-hour current. The assault boats were unprepossessing plywood and canvas craft nineteen feet in length. There were only twenty-six of them. German strength on the northern bank was unknown; in any case, the paratroopers could not count on surprise, for the crossing site was completely exposed to enemy observers.

Fifteen minutes before H-hour, Allied artillery, tanks, and mortars began to batter the German defenders on the north bank, climaxing their barrage with smoke shells. The wind blew the smoke screen to tatters. At precisely 3 P.M. the 260 men of Major Cook’s first wave waded into the shallows, hauling and shoving their awkward craft. They scrambled aboard and with paddles flailing pushed out into the deep, swift stream. Then the Germans opened fire.

Mortars, rifles, machine guns, 20-mm cannon, and 88’s thrashed the water until it looked (as a paratrooper described it) like “a school of mackerel on the feed.” Shrapnel tore through the canvas sides of the boats, knocking paratroopers sprawling. Of the twenty-six craft in the first wave, thirteen made it across.

Stunned by the ordeal, the paratroopers huddled in the lee of the north bank, retching and gasping for breath. But these men were veterans, trained as an elite force, and as they recovered physically they recovered their poise as well. Although unit organization was hopelessly scrambled, they took stock of the situation and began to move against their tormentors with deadly precision.

They raced forward to seize a sunken road, killing or scattering its German defenders and smashing machinegun positions with grenades. A pickup platoon stormed an ancient Dutch fortress that dominated the shoreline. With this strongpoint silenced, the paratroopers hurried along the roads leading to the rail and highway bridges.

Meanwhile, weary engineers

A mile and a half upstream, the Anglo-American attack on Hunner Park was well under way. During the previous night Model had reinforced the bridge defenders with a battle group from the 10th SS Panzer Division, and several 88’s were newly dug in along the north bank, sited to fire into the streets converging on Hunner Park. By now, however, the paratroopers had control of the buildings fronting on the park and were pouring a devastating fire down into the German weapons pits from the rooftops. About an hour and a half after the attack began, an all-or-nothing tank-infantry assault was launched. Charging two and three abreast, the British tanks burst into the park, closely followed by paratroopers. The stone observation tower and a heavily wooded piece of high ground were quickly overwhelmed. The defenders of the park began to withdraw.

It was now dusk, and in the dim light and drifting battle smoke an American flag was seen flying high above the north bank of the river. Taking this as a signal that the far end of the highway bridge was secured, five British tanks raced onto the bridge ramp. In fact the flag was flying from the northern end of the railroad bridge downstream, but no matter: paratroopers were just then overrunning the defenses of the highway bridge as well. German bazookamen hiding in the girders knocked out two of the tanks, but the remaining three clattered across the span, shot their way through a barricade, and just after 7 P.M. were greeted by three grinning privates of the 504th Regiment. The great prize was intact in Allied hands at last; as darkness fell, the final stretch of Hell’s Highway lay ahead.

However, the situation of the British paratroopers at Arnhem to the north had grown desperate during the day. Attempts to reinforce Colonel Frost’s men at the north end of the bridge were broken off; facing an estimated six thousand German troops, Urquhart could do no more than try to retain a bridgehead on the Lower Rhine a half dozen miles to the west of the city with the remnants of his force. That night a grim message from the Red Devils was received by the British Second Army: “Enemy attacking main bridge in strength. Situation critical for slender force.… Relief essential.…”

Arnhem is only ten miles beyond Nijmegen, but on Thursday, September 21, it might just as well have been ten light years away. The Guards Armoured Division was immobilized in Nijmegen due to shortages of ammunition, gasoline, and replacement tanks. It had virtually no supporting infantry. The 82nd Airborne was stretched near the breaking point containing attacks

Thus, the fifth day of Operation Market-Garden was frittered away, much to the frustration of the conquerors of the Nijmegen bridge. Only a trickle of tanks and other fighting vehicles crossed the hard-won span; Allied gains beyond Nijmegen were slight. And at Arnhem the last of Colonel Frost’s men, out of ammunition, had been routed from their strongholds and forced to surrender. Allied reconnaissance planes reported seeing German armored units and infantry convoys rolling south, headed toward Nijmegen, across the Arnhem bridge.

The road between Nijmegen and Arnhem runs some six feet above the low fields and orchards flanking it, making the British tanks that tried to advance northward on the next day, Friday, September 22, sitting ducks for the enemy gunners. The advance soon foundered at a roadblock in the village of Ressen, seven miles short of Arnhem.

Although the Germans now held the Arnhem bridge in strength, Horrocks believed a crossing of the Lower Rhine might still be possible by building a bridge downstream, where the Red Devils had their slender bridgehead. Horrocks’ troops eventually reached the river over back roads late in the day, but it was too late. German forces arrived on the north bank in too much strength for Horrocks to attempt a bridging operation.

Thirty miles to the south, Student’s tanks slashed across Hell’s Highway, bringing all traffic to a halt. Continued bad weather made aerial support and resupply impossible. “Waiting and waiting for the Second Army,” wrote one of the Red Devils in his diary. “The Second Army was always at the back of our minds. The thought of it made us stand up to anything.…”

On Saturday the Second Army refused to release the reserve division scheduled to be airlifted to the support of the Arnhem airhead. It is an old military maxim to reinforce success, but with each passing hour Market-Garden was looking less and less like a success. Paratroopers of the 101st Division and British tanks managed to reopen Hell’s Highway by afternoon, but not enough assault boats could be brought forward to the Lower Rhine to effectively reinforce Urquhart’s shrinking perimeter. The Red Devils were critically short of ammunition, food, water, and medical supplies; air resupply was all but impossible, although C-47 pilots repeatedly braved the German flak to try it.

On Sunday, as the Allied command groped for a way to save the battle slipping away from them, Urquhart radioed the Second Army: “Must warn you unless physical contact is made with us early 25 September [Monday] consider it unlikely we can hold out long enough.” That evening Student’s tanks cut Hell’s Highway once more.

At 9:30 A.M. on Monday Generals Browning and Horrocks made it official: Market-Garden had failed; the Arnhem airhead would be evacuated. When night fell the Red Devils began to slip away toward

Only 2,400 of the nine thousand Red Devils who had fought in and around Arnhem were rescued. When there was time for a count, it was found that in the nine days of fighting the 82nd Airborne had lost over 1,400, the 101st over 2,100. Another fifteen hundred men and seventy tanks were lost by Horrocks’ ground forces. Close to three hundred Allied planes were downed.

The Arnhem bridge — the last bridge — stayed firmly in German hands. There it would remain for seven months, until the final few weeks of the war.

Operation Market-Garden came tantalizingly close to success — a few hours saved here, a different decision made there, and everything might have been different. The weather was certainly an important factor in the failure, limiting aerial resupply and reinforcements and hampering air support. The decision to drop the Red Devils so far from Arnhem was a costly one. The pace of the Second Army’s rear echelons carrying supplies and reinforcements was hardly what Montgomery had in mind when he called for a drive of “the utmost rapidity and violence.” Allied intelligence fumbled badly in not taking reports of the presence of the two Panzer divisions more seriously. And there was pure misfortune in Market-Garden’s taking place on the very doorsteps of Model and Student, two of the most skilled German generals on the Western Front.

Most of all, however, Market-Garden failed because it was conceived on the assumption that the German army was about to collapse. The Nazis were not as close to the brink as they seemed: to push them over the edge required a far stronger force than Market-Garden was given. “Perhaps,” writes the military historian Charles B. MacDonald, “the only real fault of the plan was over-ambition.”

But if it was a failure, it was a gallant one. If boldness, imagination, and sheer raw courage deserve the reward of victory, then victory should have gone to the men of the First Allied Airborne Army. The fighting record of the ist British Airborne in Arnhem has been justly celebrated as an epic. Yet the exploits of the two American airborne divisions that defended Hell’s Highway against all odds and brilliantly won the great bridge at Nijmegen have too often been overlooked. AS General Brereton put it: “The 82nd and 101st Divisions … accomplished every one of their objectives. … In the years to come everyone will remember Arnhem, but no one will remember that two American divisions fought their hearts out in the Dutch canal country and whipped hell out of the Germans.”

“I think we might be going a bridge too far,”