Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 3

Authors: Henry Sturgis

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 3

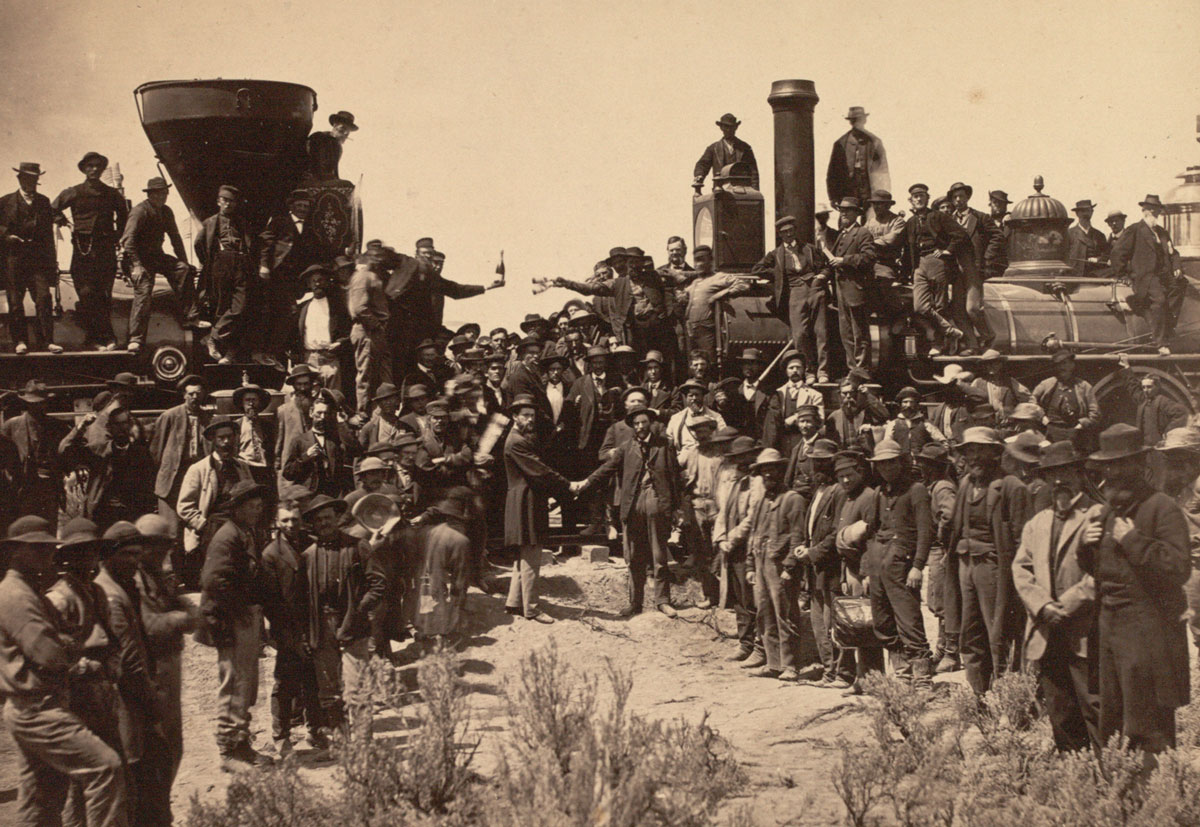

At Promontory, Utah Territory, on the raw afternoon of May 10, 1869, Leland Stanford, the beefy, pompous president of the Central Pacific Railroad, hefted a silver-plated sledge hammer while David Hewes, a dedicated railroad booster from San Francisco, stood by the golden spike he had donated to complete the laying of the nation’s first transcontinental rail line. At a nearby table sat a telegrapher, his hand on the key. Across the country lines had been cleared; when Stanford’s sledge struck the golden spike, cities on the shores of both oceans would know that America was finally and forever bound by a single spine of iron. A parade four miles long stood ready in Chicago, and at Omaha on the Missouri River, whence five years before the Union Pacific tracks had started west to meet the Central, one hundred cannon were primed for a thunderous salute. Before Stanford squared himself away to swing, a crew of Chinese tracklayers from the Central stepped forward witli the last rail of the 1,775 miles of line between San Francisco and Omaha. Just then a bystander, alive to the import of the scene, shouted to a cameraman, “Shoot!” The Chinese dropped the rail with a loud clang and scrambled for cover. It took several moments to round up the gun-shy Orientals and convince them that this shooting would not be like those they knew all too well from brutal months of pounding the line through a lawless wilderness. The rail was duly set in place.

Stanford drew back his hammer. A hush came over the assemblage—politicians, railroad dignitaries, track foremen, gaudy dancers, Irish and Chinese track hands, hunters, mountain men, gamblers, gimfighters, exconvicts, and nymphes du grade —massed in the heavy mud where the rails joined. The prevailing sounds were the hissings from the Central’s handsome locomotive Jupiter and the U.P.’s gleaming Number 119, standing one hundred feet apart at the junction point.

The telegrapher clicked the penultimate message: “All ready now. The last spike will soon be driven. The signal will lie three îlots for the commencement of the blows.” Leland Stanford swung, the silver hammer head flashing in the sun.

He missed.

The hammer thonked dismally against the tie, leaving the golden spike undriven; nonetheless the telegrapher signalled, “Dot, dot, dot.” Across the United States cannon fired, bells rang, parades went forward, prayers were said, men cheered, and ladies wept. Jupiter and 119, nswarm from headlamp to cab with shouting, bottle-waving men, nosed gingerly across the last rail until their cowcatchers almost touched. Bottles popped and champagne splashed. So far as everyone but Stanford and a group of discreet onlookers was concerned, the United States was now truly—physically—one nation indivisible. One

There had been a number of proposals earlier in the century for a transcontinental railroad, but most congressmen had found them foolish. Nevertheless, the idea gradually became more respectable. In 1845 Senator John M. Niles of Connecticut put before Congress a proposal, drawn up by his friend Asa Whitney, to set aside for a railroad 75,000,000 acres in a strip sixty miles wide from the Mississippi to the Columbia River valley. The project would finance itself from land sales, industrial development, and mining and lumbering along the route. Besides tying the northern free states to the New West, the route would be the fastest means of transshipment for ocean trade between Europe and the Far East—trade that now labored around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope.

European-Asiatic trade considerations aside, glowing reports were reaching Washington from explorers in the lush Mexican province of Upper California. There was mounting agitation for the United States to annex this splendid land and make it into a freesoil state, and that agitation gave prorailroad men yet another reason to urge the laying of a transcontinental line. But Congress failed to act favorably on the Whitney proposal. Such schemes sat poorly in the minds of southerners like Sam Houston, of the new proslavery state of Texas, and the wellconnected railroad promoter James Gadsden of South Carolina, who plumped for a southerly route to the Pacific. California was indeed a rich prize, made far richer by the discovery of gold in 1848. The only way to get there was still the Overland Mail’s seventeen-day stage ride from St. Joseph, Missouri, or the even longer sea voyage from New York to San Francisco with a Central American land-crossing en route. Men could sail around the Horn or go by oxdrawn wagon across the desert, but both ways took six months and neither could guarantee a safe arrival. Despite the need for a transcontinental line, attempts in the late eighteen forties and early fifties foundered on the question of route location—North or South?

In 1853 Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War, pushed Gadsden into the position

While such notions were being batted around in the great councils, a number of remarkably able young railroad men were at work in the Middle and Far West. Among them were Theodore Judah, Collis Huntington, Thomas Durant, and Grenville Dodge. In the fifteen years before the union at Promontory, each of them would play a crucial role in the realization of a transcontinental line. Ironically, the one whom fate would scorn was the real inspiration for the project. Ted Judah had just finished work as a location engineer for the Niagara Gorge & Erie rail line when promoters asked him to build a short line from Sacramento to FoIsom, California. The job called for only twentyone miles of local road, but Judah had something much bigger in mind—a railroad across America. “He had always read, talked, and studied the problem,” his wife, Anna, recalled years later. She remembered his saying more than once, “It will be built, and I’m going to have something to do with it.”

By August of 1855 the Sacramento-Folsom line was operative, and Jr.dah quickly moved to a series of new surveying jobs. He got to know a few of the right Californians, probed deeper and deeper into the Sierra Nevada to locate the magic route to the East—and tried to convince those who would listen that California’s destiny was bound up in his dream road.

He was so passionate and persistent that a number of people called him “Crazy Judah,” writing him off as a harmless if tiresome lunatic. They were wrong. He helped to inspire the Pacific Railroad Convention that met at San Francisco in September, 1859. A month afterward he set off for Washington, D.C. (via the trails-Isthmus route) as the convention’s lobbyist for a transcontinental road.

Judah did not get his great railroad charter from a Congress now preoccupied with slavery and possible secession, but he did set some sort of record low in expense-accountmanship. At the end of the six-month venture lie handed in his summary account: “For printing bill and circulars—$40.”

Back in California by the summer of 1860, Judah hurried to the mountains to resume his surveys, which carried him into the fall and early winter. Riding out of the mining camp of Dutch Flat one day, Judah came upon Emigrant and Donner passes, a pair of defiles about two miles apart through which an old wagon route crossed the Sierras from the Truckee River gorge

Judah charged back to Dutch Flat, went to his headquarters at the drugstore of Dr. Daniel Strong, and, on a piece of paper that was laid atop a counter, drew up “The Articles of Association of the Central Pacific Railroad of California.” He sold a few shares of stock to Strong, and left the doctor to solicit area residents (Strong peddled $46,500 worth of stock). Judah went chumming for bigger fish.

These he found early in 1861. After a number of fruitless talks with various San Francisco financiers, Judah called a meeting for a dozen prospective underwriters above a hardware store on K Street, Sacramento. Most noteworthy among them were Leland Stanford, a wealthy wholesale grocer and gubernatorial aspirant; Charles Crocker, a bull-shouldered adventurer who had made a quick pile in dry goods and now was looking for new, more exciting action; and the partners who owned the hardware store downstairs, Mark Hopkins and Collis Huntington. Hopkins was a quiet, sensible accountant, the inside man who kept the figures straight. Huntington, whom one observer later described as “a hard & cheery man, with no more soul than a shark,” was a manipulator, a money raiser.

Ted Judah was quite shrewd that night. He rightly guessed that these local merchants would not go for any pie-in-the-sky scheme about a railroad to the Missouri. So for once he suppressed his dream and sold them on the fat, short-term profits to be had by monopolizing the traffic to Nevada’s booming silver mines. Impressed, the merchants invested. Next morning a triumphant Judah told his wife at their Sacramento rooming house, “If you want to see the first work done on the Pacific Railroad, look out of your bedroom window; I am going to work there this afternoon, and I am going to have these men pay for it.” Anna’s somewhat sour rejoinder was, “It’s about time somebody else helped.”

The Central Pacific Railroad of California was officially incorporated on June 27, 1861. Its officers were Stanford, president; Huntington, vice president; Hopkins, treasurer; and Crocker, a director and chief of construction. By mid-September, Judah had completed his surveys for the line, and in early October the board resolved “that Mr. T. D. Judah, the Chief Engineer of this Company, proceed to Washington … for the purpose of procuring appropriations of land and U.S. Bonds from the Government, to aid in the construction of this road.”

Lobbyist Judah found that the Civil War, now well in progress, was a distinct asset: there were no southern legislators around to wrangle over the route or to block the bill; besides, such a line would help hold California and Nevada Territory—and their gold and silver—in the Union. Thus, at last, on July 1, 1862, President Lincoln

The act specified that two companies would build the Pacific line. The Central would lay track to the California-Nevada border, and a new concern called the Union Pacific Railroad Company was to build west from Omaha. Federal aid would include a rightof-way strip and ten alternate land sections per mile of route, on both sides of the line, for the entire distance. Furthermore, the government would lend each company—in the form of low-interest thirty-year bonds—$16,000 per mile of track in flat country, $32,000 in intermediate terrain, and $48,000 in the mountains.

A happy Ted Judah wired Sacramento: “We have drawn the elephant. Now let us see if we can harness him up.”

What Judah did not know was that, having planned the road and helped to guide the bill through Congress, he was no longer considered an asset by his colleagues in California. Crocker, Hopkins, Stanford, and particularly Huntington had decided that Judah was much too earnest—nay, passionate—an engineer to see that the real purpose of a transcontinental line was to make piles of money. He was bound to disapprove of their business meihods—anil sure enough, he did.

Stanford had been elected governor of California in 1861. By the freewheeling ethics of that era it was considered perfectly respectable for the governor to go right on being president of the Central Pacific as well. In his dual role, through some back-room arm twisting and by scattering money among voters on local bond issues, lie managed to take in well over a million dollars in public money to help get the railroad moving. Judah was horrified.

Next, Hunting-ton perceived that it was poor business to lay track at a base subsidy of $16,000 per mile it, with a little imagination, the payment could be trebled. He got a team of geologists to swear that the Sierras began at the limit of alluvial soil just outside Sacramento, rather than twenty-two miles east at the foothills. President Lincoln, distracted by the war, agreed, and the money rolled in at $48,000 to the mile. Judah was scandalized.

Finally, the “Big Four” created a company called the Associates, later renamed the Credit & Finance Company. This dummy concern was to build the railroad—at exorbitant rates. The cronies were, in effect, hiring themselves with an eye to overcharging themselves and pocketing the overage. (The device worked magnificently: it was later estimated that the directors took the government and other investors for about $36,000,000). The Associates were too much for Judah. He spoke his mind, and found himself excluded from a number of private conferences. After one such meeting the directors offered to buy him out for $100,000; alternatively, he was given the option of buying out the others if he could raise the money. Exhausted from six years of uninterrupted work and depressed with the turn of events, Judah once more boarded a steamer for the East, this time to

Before the act of 1862 was passed there had been no Union Pacific Company. Two and a half years later there still was not much of one. True, Durant had pasted together a company of which lie was vice president, general manager, principal stockholder, and prime mover. In the best Central Pacific style, Durant had devised a holding company called the Crédit Mobilier, whose function was identical to that of the Central’s Credit & Finance front.

By the spring of 1864, however, Durant had managed to lay not a single rail out of Omaha; but he did have some promising schemes afoot. For instance, Durant gave the construction contract for the first 100 miles to a crony named Herbert Hoxie. Hoxie then assigned the contract to the Crédit Mobilier at $50,000 per mile. (The U.P.’s chief engineer, Peter A. Dey, had made an honest per-mile estimate of $30,000.) Hoxie received $10,000 worth of U.P. bonds for being the stooge, and the men of the Crédit Mobilier pocketed roughly $20,000 a mile on this particular deal.

Just as the Associates’ manipulations had been the last straw for Ted Judah, so the Hoxie contract was the end for Dey. “I do not approve of the contract for building the first hundred miles from Omaha west,” he noted in a terse resignation, “and I do not care to have my name so connected with the railroad that I shall appear to endorse the contract.” Then to his friend Grenville Dodge he wrote, “I am giving up the best position this country has ever offered any man.”

Durant now began to look for a chief engineer who could lay plenty of track in a hurry, handle huge gangs of hard-handed men in the field, figlit Indians if necessary—and not worry about company finances. Hc didn’t have to look far. In return for a salary of $ 10,000 plus a packet of Crédit Mobilier stock (in his wife’s name), Grenville Dodge had the job. He also had a few tough words for Durant. “I will become chief engineer only on condition that I be given absolute control in the field,” he said. “You are about to build a railroad through a country that has neither law nor order, and whoever heads the work … must be backed up. There must be no divided interests.”

Though mildly set back, Durant was certain Dodge was the right man. Hc had surveyed all through Iowa and Nebraska and knew the land to the west. In 1859 Lincoln himself, visiting Nebraska, had consulted Dodge about a possible route for the western road. “He

When the Civil War broke out, Dodge entered the Union army as a colonel, and eventually was promoted to major general on the basis of his fighting abilities and his work in rebuilding war-torn railroads. In Washington in the spring of 1863 he had another talk with Lincoln about western railroading, in particular about the slow sales of Union Pacific stock. Dodge hinted that more government aid was indicated; this, along with some quick-footed lobbying by Durant and Huntington in 1864, produced an amended Pacific Railroad Act. The land grants were doubled, and the government loans were switched from a first-mortgage to a second-mortgage basis. The railroads now could issue their own first-mortgage bonds. Tlie gates were open for private investors. The government assumed all risks. It was the gravy train par excellence.

The stage was set for the actual driving of rails across the western half of the continent. For Dodge and the Union Pacific there were few critical engineering problems between the one-hundredth meridian and the Great Salt Lake. “There was never any very great question, from an engineering point of view,” Dodge wrote, “where the line … going west from the Missouri River should be placed. The Lord had so constructed the country that any engineer who failed to take advantage of that great open road out of the Platte Valley, and then on to Salt Lake, would not have been fit to belong to the profession.” There were, however, two major hazards: distance and Indians.

Dodge conquered distance by hiring a tough construction l)oss named Jack Casement and his brother Dan. The Casements put together an ingenious train that functioned as an assembly line on wheels, and—along with the shanty town that attached itself to the train—was nicknamed Hell on Wheels by the men who worked it.

The leading unit of the Casement train was a rail-laden flatcar. Up ahead of it, grading crews levelled the roadbed and dropped ties, five to the rail-length. Beside the llatcar, ten “iron men,” five for each 500-to-700-pound rail, pulled the iron from the car at the foreman’s command, “Away she goes!” Then, at the word “Down,” the rail boomed onto the ties with such precision that the track liners barely had to move it before the spikers and clampers fastened it into place. The llatcar also carried iron rods, steel bars, cable, rope, switchstands, and the like, as well as a complete blacksmith’s shop at the rear.

The number of cars in the train could vary. A reporter from the Salt Lake City Deseret News described a iweiity-two-iinit version: the flatcar; a feed store and saddler’s shop; a carpenter’s shop and wash-house; two sleeping cars; two eating cars; a combined kitchen, counting room, and telegrapher’s car; a general store; seven more sleeping cars; two private cars (one a kitchen, the other a parlor); another sleeper; a supply car; and two water cars.

So efficient was the Casement train and the supply system backing it up that from the outset, in the spring of 1866, the Union Pacific set a record by laying one mile of track a day. The pace was gradually stepped up to two and three and more in the final, frantic race with the Central.

As the construction crews moved west, they found to their considerable joy that they were being accompanied by a movable feast of gamblers, peddlers, and prostitutes, all eager to help them spend their money. These early camp followers posed no serious threat to the road’s progress, but by the time the rails had reached Julesburg, Colorado Territory, the pleasuremongers had been joined by a vicious auxiliary of pimps, bouncers, muggers, thieves, and gun-slingers. “Watchfires gleam over the sea-like expanse of ground outside the city,” wrote one correspondent, “while inside soldiers, herdsmen, teamsters, women, railroad men are dancing, singing, or gambling. I verily believe that there are men here who would murder a fellow creature for five dollars. Nay, there are men who have already done it, and who stalk abroad in daylight unwhipped of justice.”

“These women,” he reported of the Julesburg bawds, “are expensive articles, and come in for a large share of the money wasted. In broad daylight they may be seen gliding through the streets carrying fancy derringers slung to their waists.”

Gambling, wenching, and drinking were one thing, but shooting and knifing would not do: good track hands were too hard to find. Dodge ordered a cleanup, and Jack Casement, passing out rifles to a picked group of his toughest ironmen, walked slowly through town one summer night. Soon afterward General Dodge inquired, “Are the gamblers quiet and behaving?”

“You bet they are, General,” said Casement. “They’re out there in the graveyard.”

Cleanups had to be repeated at Cheyenne and Laramie, and once more at Corinne, Utah.

Farther west, Union Pacific workers ran into Indian trouble. Several small advance parties of grading crews were bushwhacked. In another raid an engine was derailed and the crew trapped, tomahawked, and tossed into the flaming wreckage. Occasionally a lone meat hunter or a careless stroller was scalped. But the Indians didn’t always win. One bold but not particularly bright party of braves tried to capture an iron horse alive. Taking a forty-foot leather rope that their medicine man had infused with magic, two braves lay on either side of the track, the rope slack as an engine approached. When the locomotive was a few yards away the Indians leaped up and strained against the medicine rope. The two Indians closest to the tracks were swept beneath the wheels, and the others limped home with their bruises.

Occasionally Dodge, who had a dramatic flair, issued such ringing pronouncements as, “We’ve got to clean the damn Indians out or give up building the Union Pacific,” but the fact was that the Indian trouble was more terrifying in the telling

While the work of road building continued, the work of money-making more than kept pace. The Hoxie contract remained in effect for the first 247 westward miles of track. It was superseded for the next 667 by the so-called Ames contract. Oakes Ames was a member of the Crédit Mobilier, brother of the president of the Union Pacific—and a United States representative from Massachusetts. Ames was to assign the contract to a group of men (brother Oliver among them) representing the Crédit Mobilier.

Actually, the first 228 miles of trackage under the Ames contract had already been laid, at a per-mile cost of $27,500. Nonetheless, the contract specified per-mile payments —by the Union Pacific to the Crédit Mobilier—of $43,500. The Crédit Mobilier, then, had realized a profit of $3,648,000 on the Ames contract even while the ink on it was drying.

The fact that Oakes Ames was a member of Congress was a great help, since it allowed him to distribute juicy chunks of Crédit Mobilier securities “where they will do the most good”—among his legislative peers. The securities went to such friends of the Union Pacific as Speaker of the House (and Vice President-to-be under Grant) Schuyler Colfax, to Representative (and future presidental nominee) James G. Blaine, and to Representative (and future President) James A. Garfield. A score of others were implicated.

The kited profits from the Ames contract and succeeding arrangements have been estimated at anywhere from fourteen to fifty million dollars. Durant should have been content to let more than enough alone. But he began tampering with Dodge’s road building, trying to make the route longer to get even more subsidy money. Dodge would have none of it, and one day shouted down Durant in front of the men. “You are now going to learn,” Dodge bellowed, “that the men working for the Union Pacific will take orders from me and not from you. If you interfere there will be trouble—trouble from the government, from the Army, and from the men themselves.”

Scraping up a pile of evidence on what he considered incompetence and nonfeasance, Durant gambled on an official showdown. The referee was none other than General U. S. Grant, Republican nominee for President.

On July 26, 1868, at Fort Sanders in Wyoming Territory, Grant heard the two men out. Durant charged that Dodge had selected a poor route, had wasted money, and had failed to get the line to Salt Lake. Grant said, “What about it, Dodge?”

“Just this,” said

Grant pondered, then spoke again, slowly. “The government expects the railroad company to meet its obligations. And the government expects General Dodge to remain with the road as its chief engineer until it is completed.”

That was plain enough. Durant leaped up, stuck out his hand to his chief engineer, and said heartily, “I withdraw my objections. We all want Dodge to stay with the road.”

Out in California the Central Pacific had had an entirely different set of problems. Once Judah was out of the way there was little but harmony within the line’s management. The Indians were no trouble at all—Crocker kept them happy by handing the chiefs passes to ride the day coaches and by letting the braves hitchhike on freight cars. The terrain, however, was another matter. The rugged defiles of the Sierras had killed off hundreds of pioneers; they claimed hundreds of railroad laborers before the Central got through.

The man chosen to lead the assault on the Sierras was Charley Crocker, who noted modestly that he “grew up as a sort of leader.” (Later he would boast, “I built the Central Pacific.”) Of all the people who had a hand in its building, Crocker certainly was the most colorful. Roaring up and down the grade ceaselessly, bragging, bullying, paying the men from a bag of gold coins slung from his saddle, Crocker drove the track layers toward the summit passes. Yet, amid all this energy would come sudden lapses into complete torpor. Flat on his back, with a Chinese manservant fanning him with a branch, he would not speak, get up, or even do paper work. Then, just as abruptly, he would be back in the saddle, full of bombast and shouting profane orders.

But the Central was having labor troubles. In the spring and summer of 1865, roughly ninety per cent of the white workers who had signed on in San Francisco deserted after a week or so at railhead—they had been looking for a free ride toward the gold and silver mines of the Sierras. Crocker considered replacing them with Mexican peons but finally brought in a trial batch of fifty Chinese from San Francisco. The other Central directors protested the scheme, and the remaining American laborers hooted at the tiny, pig-tailed coolies, most of them under five feet in height and averaging 110 pounds, padding along in their floppy blue cotton trousers.

The Chinese ignored the jibes, silently pecking at the grade with their shovels and wheeling away earth in modest barrowloads. At the end of the first day, to the embarrassment of the regular hands, the Chinese grade was smoother and the work-line farther advanced than any of the others. Better yet, instead of getting drunk, fighting, and generally disrupting the camp in the evening, the Chinese carefully bathed with buckets of hot water, boiled their

Crocker ordered up another group of Chinese, then another; by the winter of 1866–67 there were more than 2,000 Orientals in the Central’s work force. As the going got tougher so did the Chinese. These men were, as Crocker had pointed out from the start, descended from the people who built the Great Wall; the matter of building a rail line over the Sierras, at the cost of a few hundred lives, was barely to be noticed in the great scheme of things.

When the line hit a sheer wall of rock thirteen miles from the summit, the Chinese wove baskets of reeds, lowered themselves down the sides of the precipice to plant nitroglycerin charges, and then hauled quickly up the rock face while the nitro blew.

Crocker decided against using a steam drill on the summit tunnel because his one steam-power machine was already being used to hoist blasted rock. So the coolies stoically burrowed down through twenty-foot snowdrifts to chip away with hand chisels. They worked week after week in the frozen gloom of the shafts; sometimes progress was no more than eight inches a day through the solid granite.

In the fall of 1866 Crocker had come to feel that the Central’s slow progress was giving the U.P. a big advantage in the race for mileage (and government subsidies), so he decided to bypass the unfinished summit tunnel and try to lay track down the eastern slope of the Sierras before spring. Teams of five hundred Chinese hitched themselves to enormous log sleds and hauled three locomotives, forty cars, and enough iron for forty miles of track through the blizzards of the High Sierra. Avalanches swept through the work camps, carrying whole bunkhouses full of men to death in canyon bottoms; the Chinese offered quiet prayers, and waited for spring to retrieve their dead. The phrase “Not a Chinaman’s chance” was coined that terrible winter. It was just as applicable the next.

At last, by May 4, 1868, the Central’s rails reached the Truckee River at the Nevada border. The Sierra ordeal was over. There remained the safe though still arduous business of racing eastward to beat the U.P. out of as many $32,000 miles as possible. Since the government had never bothered to specify a meeting point, Crocker and the Casement boys spurred furiously ahead.

Whenever they came to rivers or ravines, both Central and U.P. gangs threw up flimsy trestles, promising to finish the job later. At the few remaining short tunnel sites, they carved out hasty bypasses and rushed on. Through the final winter of 1868–69, they flung down track on snow and even across river ice. At one point Dodge laid rail on a frozen stream bank so narrow and precarious that the track, together with an entire train, slid off into the water.

When the tracks finally approached each other on the great curve around the northern end of

In early April of 1869 President Grant informed Dodge that he had had enough of the nonsense and would do his best to withhold future bonds if the U.P. and the Central could not agree on a junction point. Dodge, Durant, and Huntington conferred. The Central agreed to stop at Promontory if the Union Pacific would sell its trackage thence east to Ogden. That was mutually acceptable, and Congress approved the agreement by joint resolution.

Even with the meeting place set and the money virtually counted, the rivals seemed unable to stop battling. U.P. crews had, at one point, set a one-day’s trackage record of eight and a half miles. Crocker, who could not stand to be beaten, boasted that the Central could lay ten. Durant bet $10,000 against it. On April 29 a handpicked gang of Crocker’s men did indeed lay 3,520 rails, with 55,000 spikes and 14,080 bolts, from sunup to sundown (including a brief lunch break) for ten miles and two hundred feet. The rewards, however, were slight: there is no evidence that Durant ever paid off.

Besides, the two U.P. officials had more to worry about than wagering. The day before the record was set Durant was kidnapped from his special train by workers striking for back pay. Dodge had to scramble to obtain nearly a million dollars from the East to placate the angry track hands.

On May 7 it began to rain, and for the next two and a half days it poured. Officers from each company squished through the mud to champagne parties in the various rail cars that had pulled in for the spikedriving ceremony. The track hands, meanwhile, were getting drunk in Promontory’s ramshackle saloons.

And then, on the tenth, the rails met, and Stanford swung his futile swing. In San Francisco young Bret Harte, editor of the Overland Monthly , jotted down a poem for use in his next editorial:

What they may have said was that this was one hell of a way to build a railroad. For in addition to all the haste, waste, and thievery, two of the reasons for rushing ahead with the road had evaporated—and a third was yet to come into being. In 1869 the Suez Canal opened, scrapping the European-Oriental trade route scheme. The Civil War had ended long since, and with it the serious North-South rivalry for political domination of the West. Third, although a railroad had indeed crossed the great American desert, there was precious little freight and

Within a few years the Union Pacific was sometimes hauling one lone passenger a day; it was soon on its way to receivership, where it duly landed. By 1872 the stench from Crédit Mobilier had finally become too much even for Congress; an investigation led to a vote of censure for Oakes Ames, and left spatterings of mud that could never be expunged from the coattails of the others involved.

But despite everything—the financial flop, the congressional scandal, the misplaced hopes for an Oriental trade route, the travail of the building work, the blizzards, raids, gunfights, and interminable wrangling—two decades after the line was completed, a continent had been transformed. The Indians, pushed back and hemmed in now by rail-borne troops carrying repeating rifles and Catling guns, began to sink into the despair of their impoverished reservations. The buffalo, too, were doomed by the railroad. Forever after the high plains and mountains would belong to the white man.

By 1880 three more lines had crossed to the Pacific, and parts of the prairie bloomed into food-growing regions as lush as any in the world. Desert shanty towns touched by track were transformed into shining cities. Boston and Philadelphia now dined on Colorado beef, and fresh-caught Pacific salmon became a delicacy in Minneapolis. Chicago grew to be the world’s busiest railhead, and America was becoming the most powerful industrial nation the world had ever seen. As one Gilded Age President put it for an audience at Hudson College in New York: “The railway is the greatest centralizing force of modern times.” And President James Garfield was something of an authority on the value of railroads.

CREDIT MOBILIER