Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

The North started winning the Civil War in January 1862, but nobody knew it yet. Hindsight hadn’t had time to kick in. Plus, it happened out in the middle of America, far from the conflict’s media-massed Virginia front yard. And the man who would lead the victory, from western Appalachia all the way to Appomattox in 1865, was the unlikeliest candidate then imaginable.

The West Point credentials of President Lincoln’s top commanders in late 1861 belied any intent of attacking the enemy. In front of Washington City, egocentric General-in-Chief George McClellan preened in dread, training and equipping the already first-rate Army of the Potomac while studiously avoiding combat with the undermanned Confederate States of America. He was outnumbered, he claimed.

In Kentucky, Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell acted similarly with his Army of the Ohio. Like McClellan, Buell ignored Lincoln’s orders to advance. And in St. Louis Lincoln’s other western chief, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, kept to the Planter House hotel and dispatched minions to chase guerrillas across Missouri. More focused on army politics than war, Halleck and Buell appeared determined to force the other to risk making the first mistake.

Enter an unloved Halleck subordinate.

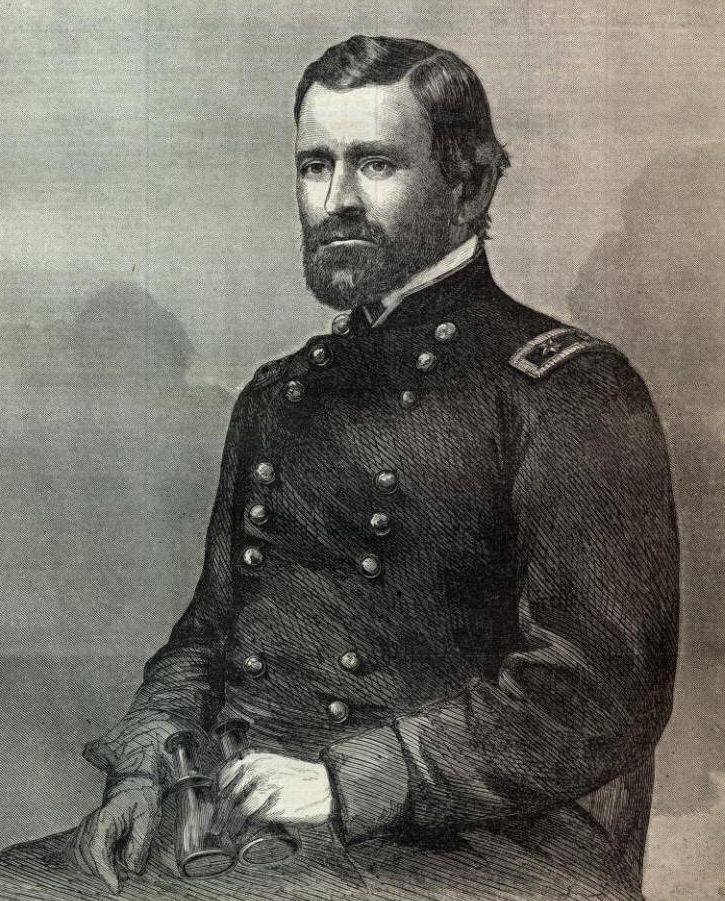

Ulysses S. Grant was an accidental brigadier general. When the war broke out, despite being a West Pointer and a veteran of the Mexican War, he barely got back into the army. Conventional military wisdom labeled him a sot. He had bailed out of the prewar U.S. regulars in 1854 under rumored threat of charges of drunkenness on duty—resigning, a friend later said, rather than have his wife find out. A couple of years later, ex-comrades saw him in shabby clothes on St. Louis street corners peddling firewood. Asked to explain, he said, “I am solving the problem of poverty.”

By any peacetime measure, Grant had been at best a middling officer. He had attended West Point unwillingly, cared little for his studies there, and possessed no martial ambition or pride in the uniform. Post graduation, he served in the antebellum army for 11 years because he saw nothing more promising to do. He rose only to the rank of captain—in part, no doubt, because his birth, compared to the upper-crust West Pointers of his era, had been humble. His father was a tanner.

So when the war came, he was ignored. He managed to re-enter the army only when the governor of Illinois named him to replace a colonel who had been unable to handle the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Yet within two months, the new colonel found himself a brigadier general, thanks to an Illinois congressman who wanted as many Illinois generals as he could get.

Grant soon commanded a 20,000-man army in the military district of Cairo, Illinois, which sat on the state’s southern tip looking down the Mississippi River. As the nation’s primary commercial highway, the Mississippi was a top Union preoccupation. Retaking its Confederate