Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2018 | Volume 63, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2018 | Volume 63, Issue 1

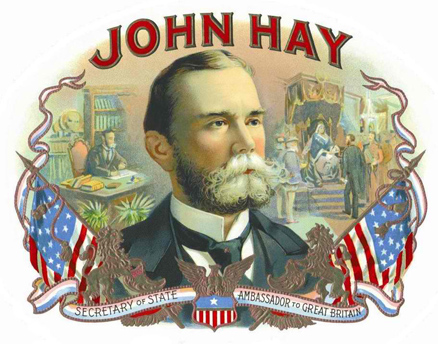

Less than three weeks before his death, John Milton Hay awoke in his cabin room on the RMS Baltic as the great ocean liner, still the jewel of the White Star Line, steamed a course from Liverpool to New York. He reached for his diary and composed one of its final entries.

It was June 1905. Electric lights and streetcars lined hundreds of American towns. Phonographs and telephones were quickly becoming common fixtures in middle-class living rooms, and for a nickel city folk could gaze into large wood and steel boxes and marvel at moving picture images of prizefighters, ballplayers, and ballerinas. John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie represented the extremes of American wealth and power. It had already been two years since the Wright brothers conducted the first manned test flight of an airplane. In Germany, the theoretical physicist Albert Einstein had recently published a paper on the “photoelectric effect” was fast at work developing his theory of relativity. In Vienna, Sigmund Freud published his path-breaking volume, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.

In his youth, John Hay could scarcely have imagined this world. A child of the western prairie, he was raised in the age of iron and grew to manhood in the age of steel. A noted poet and historian, former newspaper editor and railroad executive, Hay had served as U.S. ambassador to Britain and, since 1898, secretary of state—first under President William McKinley and then, after 1901, under President Theodore Roosevelt. He was one of the most powerful men in the world. But his bright spirit was fast burning out a frail body. In his final weeks, his Mind wandered back to the simpler world of his youth.

“I dreamed last night that I was in Washington,” Hay confided to his diary, “and that I went to the White House to report to the President, who turned out to be Mr. Lincoln. He was very kind and considerate, and sympathetic about my illness. He gave me two unimportant letters to answer. I was pleased that this slight order was within my power to obey. I was not in the least surprised at Lincoln’s presence in the White House. But the whole impression of the dream was one of overpowering melancholy.”

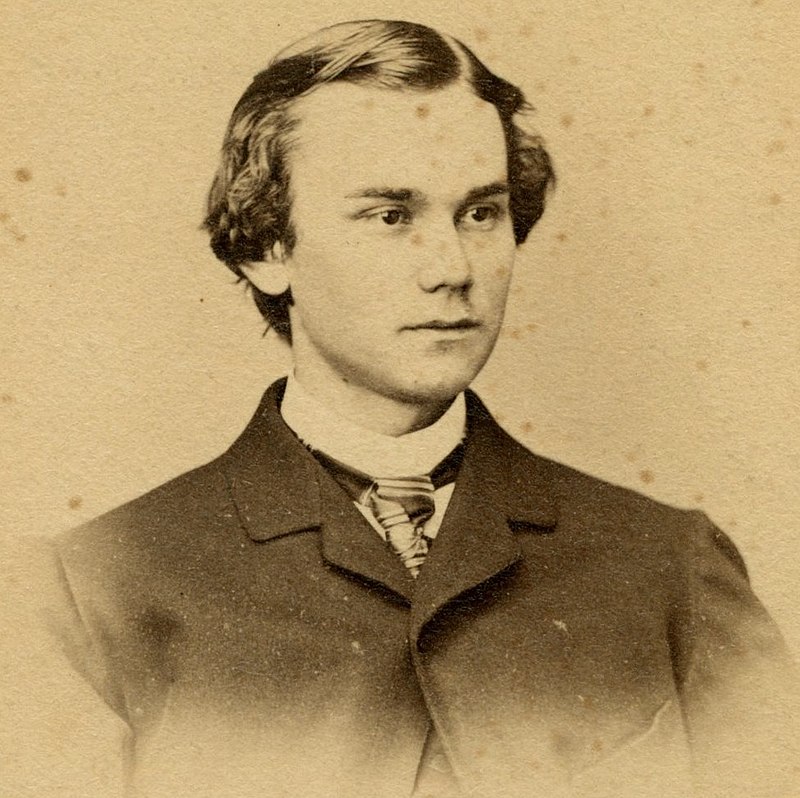

him to be his assistant in the White House. " data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="91cd3c62-1da1-4fd7-8a04-da6eeb088a45" height="335" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/John_George_Nicolay_c1855-65.jpg" width="268" loading="lazy">

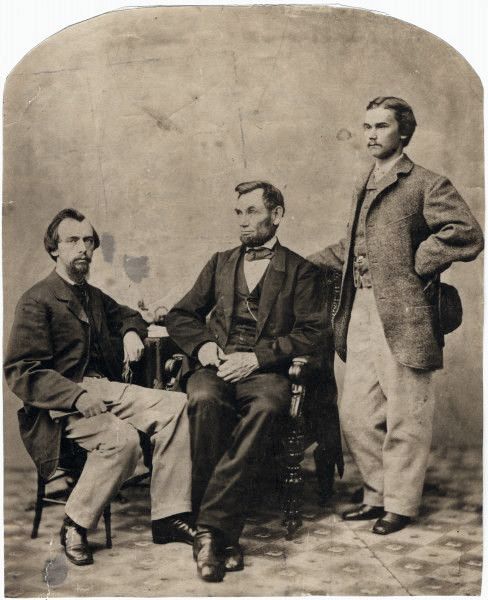

John Hay and John Nicolay were prairie boys who met in 1851 and forged a close friendship that endured over a half century. Fortune placed them in the right place (Springfield, Illinois) at the right time (1860) and offered them a front-row seat to one of the most tumultuous political and military upheavals in American history, then or since.

As Abraham Lincoln’s private secretaries, they became, both literally and figuratively, closer to the president than anyone outside his immediate family. Still young men in their twenties, they lived and worked on the second floor of the White House, performing the roles and functions of a modern-day chief of staff, press secretary, political director, and presidential body man. Above all, they guarded the “last door which opens into the awful presence” of the commander in chief, in the words of Noah Brooks, a journalist and one of many Washington insiders who coveted their jobs, resented their influence, and thought them a little too big for their britches (“a fault for which it seems to me either Nature or our tailors are to blame,” Hay once quipped). “These . . . Secretaries are young men,” Brooks grumbled, “and the least said of them the better, perhaps.”

In demeanor and temperament, they could not have been more different. Short-tempered and dyspeptic, Nicolay cut a brooding figure to those seeking the president’s time or favor. William Stoddard, an assistant secretary under their supervision, later remarked that Nicolay was “decidedly German in his manner of telling men what he thought of them . . . People who do not like him—because they cannot use him, perhaps—say he is sour and crusty, and it is a grand good thing, then, that he is.”

Hay cultivated a softer image. He was, in the words of his contemporaries, a “comely young man with peach-blossom face,” “very witty—boyish in his manner, yet deep enough—bubbling over with some brilliant speech.” An instant fixture in Washington social circles, fast friend of Robert Todd Lincoln’s, and favorite among Republican congressmen who haunted the White House halls, he projected a youthful dash that balanced out Nicolay’s more grim bearing.