Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2018 | Volume 63, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2018 | Volume 63, Issue 2

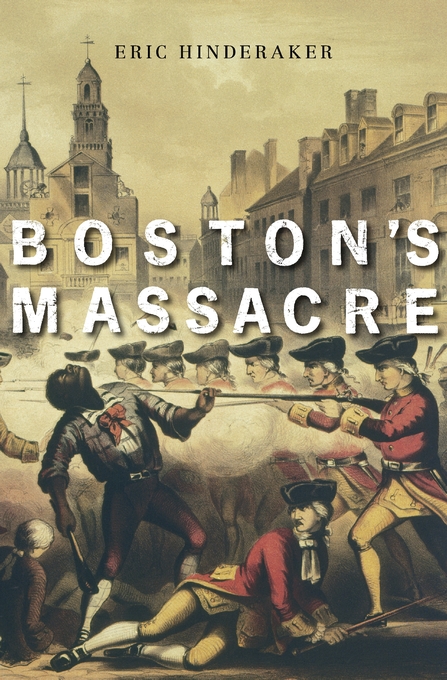

A little after 9:00 p.m. on March 5, 1770, a detachment of British soldiers fired into a crowd of townspeople on King Street in Boston, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The result—the “Boston Massacre”—has echoed through the pages of newspapers, pamphlets, and history books ever since. It is perhaps the most densely described incident in early American history (with more than two hundred eyewitness accounts), yet the descriptions are sufficiently contradictory to make the unfolding sequence of events surprisingly hard to pin down. To say what happened would seem to be a straightforward task, but, in many ways, the Boston Massacre remains an irreducible mystery.

The human mind does not simply recall everything it sees, recording an objective and unerring account of events as they happen. Instead, in moments of stress, it picks up patches of highly subjective impressions. Only through narrative—only by subsequently devising a story that threads those patches together into a meaningful pattern—do the instantaneous effects of a dramatic episode like the shootings in King Street acquire a form that can be recalled, interpreted, and argued for. The Boston Massacre offers an unusual opportunity to observe impressionistic flashes gradually take on the shape of competing narratives, and then to trace the evolution of those narratives across a long span of time.

In the abundant literature on historical memory, most of the attention has been given to momentous events. One large body of work in memory studies relates to the place of catastrophe—especially the Holocaust (known in Israel as the Shoah)—in the historical experience of Jews. In U.S. history, memory studies have paid close attention to the ways in which the Civil War is remembered, especially among southerners.’ The Boston Massacre is very different from the Holocaust and the Civil War. In a critical way, it is precisely their opposite: while those later occurrences were so monumental in scale and implication that it was difficult to assimilate their meanings, the Boston Massacre was, by comparison, an inconsequential skirmish. Similar scrapes occur often, and are just as quickly forgotten. But the shootings in King Street were not forgotten. They were amplified and politicized in ways that made the Boston Massacre seem to be an event of transcendent importance. This use of historical memory differs dramatically from the cases that dominate the literature on the subject, and it deserves careful and extended consideration.

Simply to call the Boston shootings a “massacre” was to make a claim for the event’s significance. Townspeople immediately referred to the shootings as the ‘bloody massacre” in King Street; within weeks, that phrase had repeatedly cropped up in print. Though it is inflammatory, the term “massacre” is also vague. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, its primary definition