Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue | Volume 63, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue | Volume 63, Issue 3

In many ways, 1918 is closer to us than we are inclined to think.

Look at Fifth Avenue in New York (or Regent Street in London, or the Champs-Elysées). Many of their present buildings were there a century ago. Automobiles, telephones, elevators, electric power, electric lights, specks of droning airplanes in the sky—there they were in 1918. Now count back a hundred years from 1918. That was 1818, when just about everything looked different. Everything was different: the cities, their buildings, the lives of the men and women outside and inside their houses, as well as the furniture of their minds.

But many of the ideas current in 1918 are still current today: Making the World Safe for Democracy; the Self-Determination of Peoples; the Emancipation of Women; International Organizations; a World Community of Nations; “Progress.” The twentieth century was a short century, having burst forth in 1914, formed and marked by two world wars and the Cold War, ending in 1989.

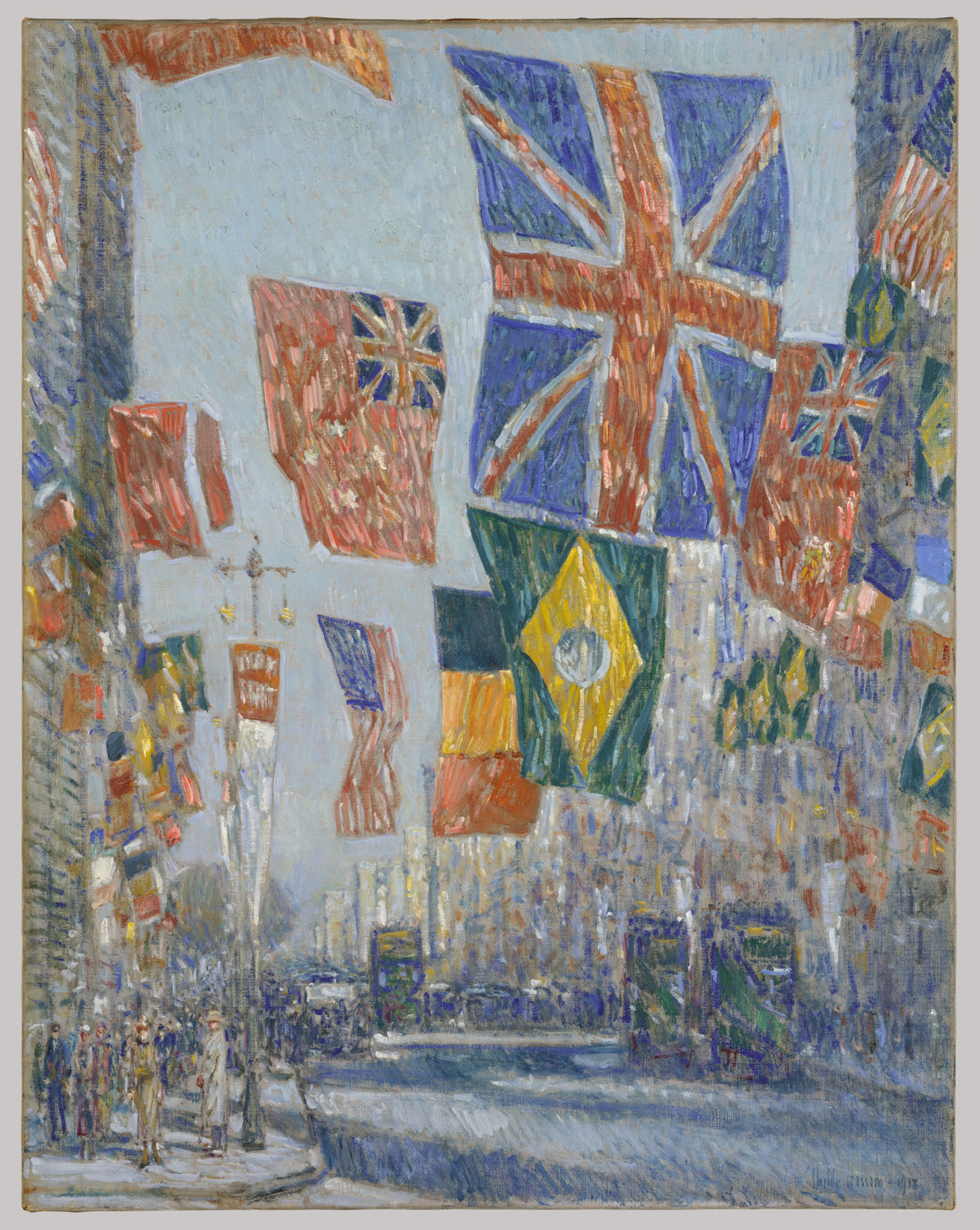

In many other ways, 1918 is farther from us than we are inclined to think. After taking comfort—and, more important, pleasure—from a picture of Fifth Avenue in 1918 (I am thinking of that splendid painting by Childe Hassam, with all those Allied flags waving, dramatic poppies in a wheat-colored field of sun-bleached architecture), look closer; lean downward; try to look inside. The people are different from us, and I do not mean only the difference of two or three generations: They look different, because their composition and their clothes and their manners and their attitudes and aspirations are different. So are the interiors of those still-standing buildings, what there is and what goes on inside them: their furnishings, in most cases not only their inhabitants but the functions of their rooms. Yes, Fifth Avenue is different, New York is different, America is different, the world is different. The twentieth century is gone.

It was, in many ways, the American century. In 1898 the United States became a world power—not because of some kind of geopolitical constellation, not because of the size of its armed forces, but because that was what the American government and the majority of the American people wanted. Before 1898 the United States was the greatest power in the Western Hemisphere. Twenty years later the United States chose to enter the greatest of European wars (the very term world war was an American invention, circa 1915). In 1918 it decided the outcome of the war. By Armistice Day the United States was more than a World Power; it was the greatest power in the world.

That was more than a milestone in the history of the United States. It was a turning point: the greatest turning point in its history since the Civil War and perhaps the greatest turning point since its very establishment. For more than three centuries the colonists and Americans were moving westward, away from Europe. The trickle, and later the flow, of immigrants moved westward too, across the Atlantic, away from Europe. When foreign armies crossed the Atlantic, it was westward, from the Old World to the New. Now, for the first time in history, this was reversed. Two million American soldiers were sent eastward through the Atlantic, to help decide a great war in Europe.

That was an event far more important—and decisive—than was the Russian Revolution in 1917, both in the short and in the long run. In early 1918, Russia dropped out of the war. The United States entered it. Russia abandoned its European allies. The United States came in to join them. In 1918 the Allies were able to defeat Germany and win the war, even without Russia (something that would not be possible in another world war). The presence of an American army on the battlefield proved to be more decisive than the absence of the Russians. In the long run, too, the twentieth century turned out to be the American century, on all levels, ranging from world politics to popular democracy and mass culture. Compared with this, the influence of communism and the emulation of the Soviet Union were minimal. The exaggeration of the importance of communism blinded, willfully, not only many intellectuals but many Americans, pro-Communists and anti-Communists, developing into a popular ideological view of the world. In 1967 I was astonished to find how here, in America, article after article, book after book was devoted to commemorating and analyzing the importance of the Russian Communist Revolution on its fiftieth anniversary, while hardly any notice was paid to the commemoration of the American entry into World War I in 1917.

For a long time, Americans believed that the destiny of their country was to differ from the Old World. Beginning in the 1890s, and culminating in 1918, this fundamental creed changed subtly. Many Americans were now inclined to believe that it was the destiny of the United States to provide a model for the Old World. For a while these two essentially contradictory beliefs resided together in many American minds. In 1918 the second belief had temporarily overcome the first. This was the result of a revolution of American attitudes that—on the popular, rather than on the political, level—still awaits a profound treatment by a masterful historian. In 1914 not one American in a thousand thought that the United States would, or should, intervene in the great European war. In less than three years that changed. By 1917 most Americans were willing—and many were eager—to go Over There, to decide