Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

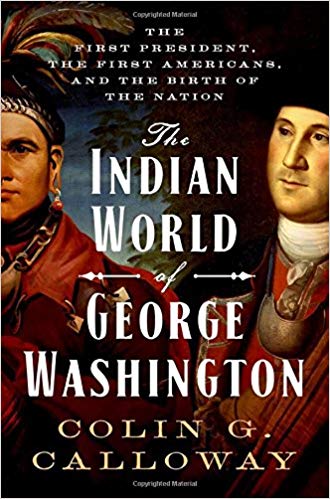

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist The Indian World of George Washington, by Colin Calloway (Oxford University Press).

On Saturday afternoon, June 14, 1794, Washington welcomed a delegation of 13 Cherokee chiefs to his Market Street home in Philadelphia. They were in the city to conduct treaty negotiations, and the members of Washington's cabinet — Jefferson, Hamilton, Knox, and Colonel Timothy Pickering — were also present.

In accordance with Native American diplomatic protocol, everyone present smoked and passed around the long-stemmed pipe, in ritual preparation for good talks and in a sacred commitment to speak truth and honor pledges made. The president delivered a speech that had been written in advance. Several of the Cherokee chiefs spoke. Everyone ate and drank “plentifully of cake & wine,” and the chiefs left “seemingly well pleased.”

Four weeks later, Washington met with a delegation of Chickasaws he had invited to Philadelphia. He delivered a short speech, expressing his love for the Chickasaws and his gratitude for their assistance as scouts on American campaigns against the tribes north of the Ohio, and referred them to Henry Knox for other business. As usual, he puffed on the pipe, ate, and drank with them.

The image of Washington smoking and dining with Indian chiefs does not mesh with depictions of the Father of the Nation as stiff, formal, and aloof, but it reminds us that in Washington's day the government dealt with Indians as foreign nations rather than domestic subjects. The still-precarious republic dared not ignore the still powerful Indian nations on its frontiers. In dealing with the Indians, Henry Knox advised the new president, “Every proper expedient that can be devised to gain their affections, and attach them to the interest of the Union, should be adopted.”

Deeply conscious of how he performed in his role as the first president, and an accomplished political actor, Washington engaged in the performative aspects of Indian diplomacy, sharing the calumet pipe and exchanging strings and belts of wampum-purple and white beads made from marine shells and woven into geometric patterns that reinforced and recorded the speaker's words. New York Indian commissioners explained