Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Steve Inskeep, the host of NPR's Morning Edition, has recently published Imperfect Union: How Jessie and John Frémont Mapped the West, Invented Celebrity, and Helped Cause the Civil War, from which this essay was adapted.

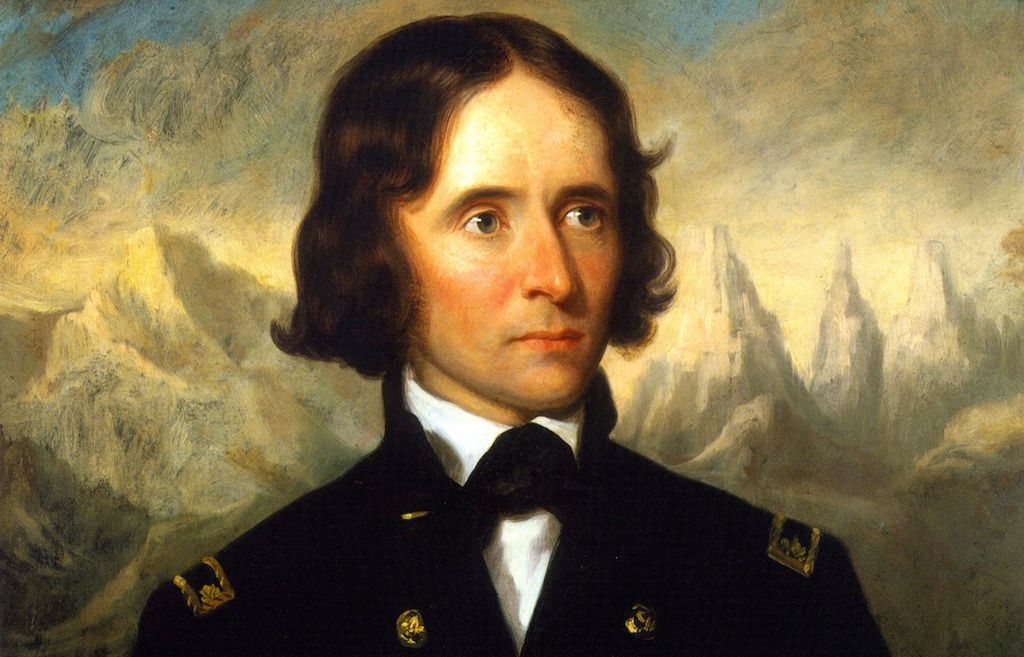

Of the many times John C. Frémont visited St. Louis, the most auspicious came in 1845. He was a 32-year-old U.S. Army captain with shoulder-length hair and a thoughtful expression. Arriving on a steamboat from the east on May 30, he disembarked at the crowded waterfront with two companions: Jacob Dodson, a son of free black house servants from Washington, D.C.; and William Chinook, an Indian from the faraway land called Oregon. It was fitting that Captain Frémont reached St. Louis with men from far to the west and east. His mission was to connect the Atlantic world to the Pacific, surmounting the natural barriers between.

Frémont served in an army unit called the Corps of Topographical Engineers, which had assigned him to draw maps of travel routes through the Louisiana Purchase. Twice in the preceding three years he had recruited small groups of skilled civilians to join him on expeditions that ranged across thousands of miles of prairies, mountains, and deserts. Each time their starting point was St. Louis, the commercial hub of Missouri, which was the westernmost of the United States. Now Frémont was about to command his third expedition, and his preparations in St. Louis should have been routine. He needed to hire men and buy supplies — camping equipment, rifles, food, brandy, and coffee. (The coffee was vital; he had run out once on the prairie, a painful mistake he would never repeat.)

But something happened as Captain Frémont made his customary rounds. His arrival was mentioned in a local newspaper, which created an unmanageable situation. James Theodore Talbot, a twenty-year-old aide who joined him in St. Louis, described Frémont’s problem in a letter to his mother.

“He was assailed by people anxious to accompany him” on his expedition, Talbot wrote. “Wherever he goes he gathers a little train.” The job seekers would not let him alone. Declining to stay with Talbot at the Planter’s House Hotel, where he might be spotted, the captain “hid himself in some French house down the City.” So many men asked for him at the hotel that a clerk vowed to put up a sign reading, “Captain Frémont Did Not Stay Here.”

Frémont spread the word that he would meet potential recruits at a warehouse, where he might stand on a barrel packed with tobacco leaves to address them. But when he arrived before ten o’clock on the morning of June 2, he found an unruly mass. “You ought to