Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 3

GALVESTON, TEXAS, June 19, 1865 — A balding, brush-bearded officer in Union blue steps onto the balcony of the finest villa in this coastal town. On the plaza below, hundreds of Texans, black and white, wonder what this is all about. Major General Gordon Granger holds out a parched paper and begins.

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. . .”

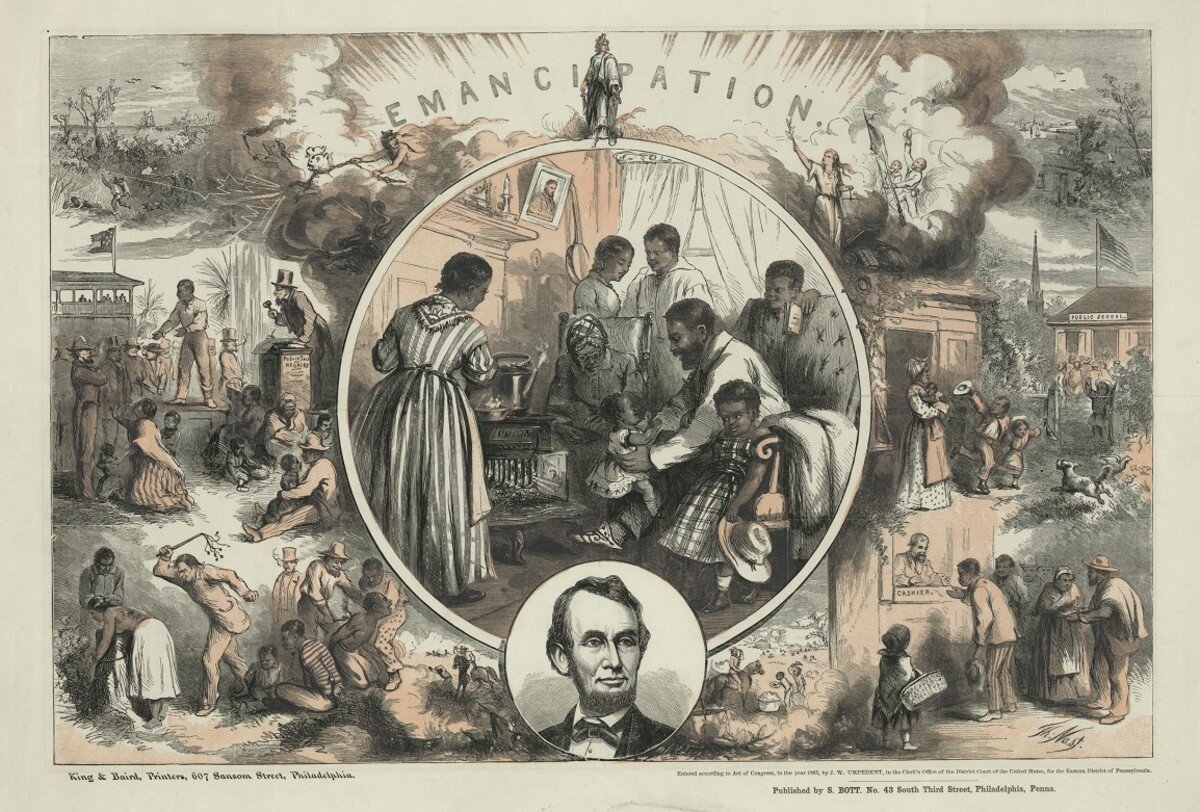

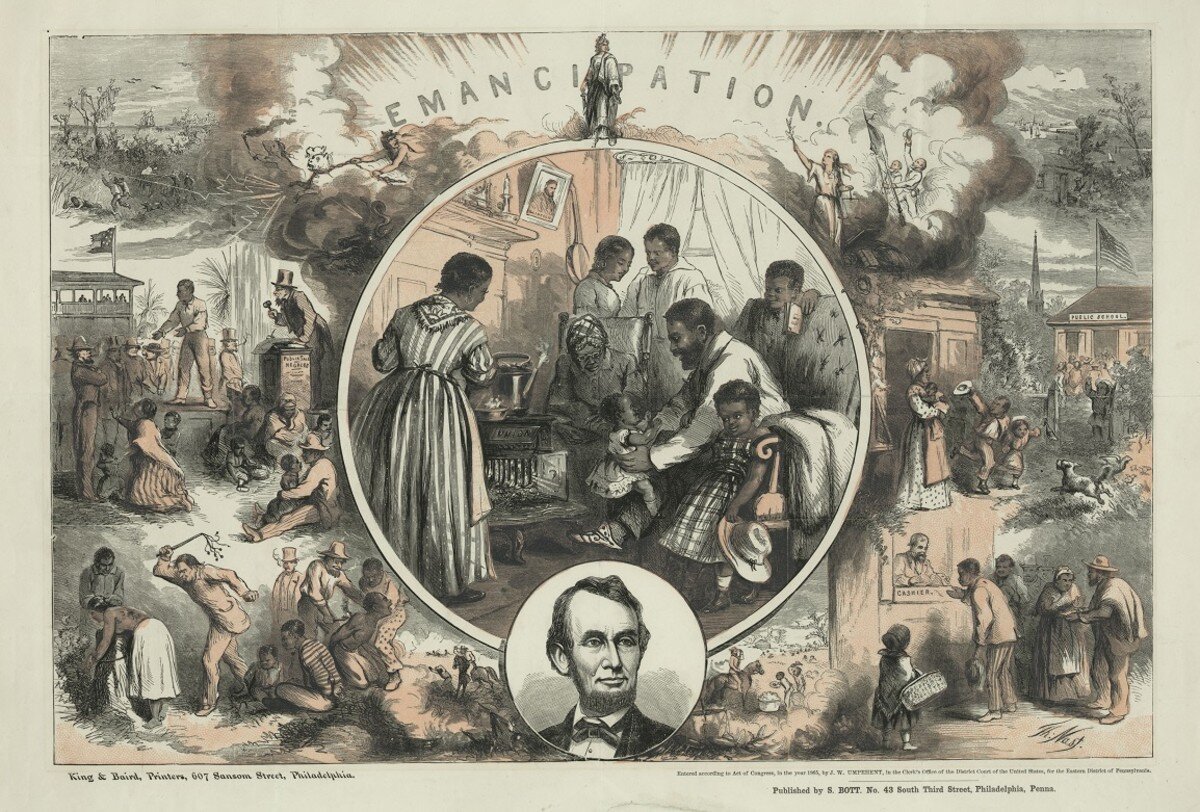

The story goes that Lincoln freed the slaves. In 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation. Hallelujah. But the decree meant nothing without enforcement, and slaves across the South remained in bondage until Union troops arrived, plantation by plantation. Slaves called their liberation “the breaking up.”

Many stories are told about why freedom took more than two years to reach Texas. Perhaps a messenger bringing the glorious news was shot down. Or slaveholders, wanting one more harvest, withheld news of the war’s end back in April. But when the word finally reached Galveston, slavery’s last stronghold fell. Free at last!

Major General Granger continues reading but no one is listening. The celebration has begun. Some shout and dance. Others fall to their knees and weep. A few freely enter former masters’ homes and put on their clothes. Song. Spirit. Jubilee. And the date goes down in history — June nineteenth, soon shortened to Juneteenth.

"Juneteenth is a day when we pray for peace and liberty for all.”

For the rest of the century, former slaves remembered. Each Juneteenth, they gathered to share stories, scripture, spirituals. Barbecue and baseball. And until Jim Crow laws arose, Juneteenth featured instructions on how to vote. When white landowners resisted, denying ex-slaves turned sharecroppers their day off, freedmen pooled meager wages, buying parkland to host the annual revelry. Emancipation Park in Houston and Austin. Booker T. Washington Park elsewhere. And then. . .

Beginning about 1900, Confederate statues arose from Richmond to New Orleans. Novels and movies rewrote the past. Seems all those slaves had been contented, well cared for. “Never was there happier dependence of labor and capital on each other,” recalled Confederate president Jefferson Davis. In the war’s wake, Reconstruction became “the tragic era,” freed slaves raping and pillaging, a government run by Negroes, the South only “redeemed” by the heroic Klan. See “Birth of a Nation.” See “Gone With the Wind.” On second thought, don’t.

Faced with myth and rising violence, Juneteenth laid low. Only in the 1940s did its embers stir. Then came the Civil Rights Movement, too busy to celebrate. Finally, in the 1970s, Juneteenth came alive again.

On January 1, 1980, Texas declared Juneteenth a holiday. And today, although 46 other states have since followed suit, Juneteenth is more than just a holiday. It is a cultural touchstone, Independence Day for those whose history recalls the time when each Fourth of July, as Frederick Douglass said, revealed “the gross injustice and cruelty” of slavery.