Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Authors: Eleanor Jones Harvey

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Eleanor Jones Harvey is a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She organized the recent exhibition on Humboldt at the museum and was one of the authors of the book, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture (Princeton University Press), in which portions of this essay appeared.

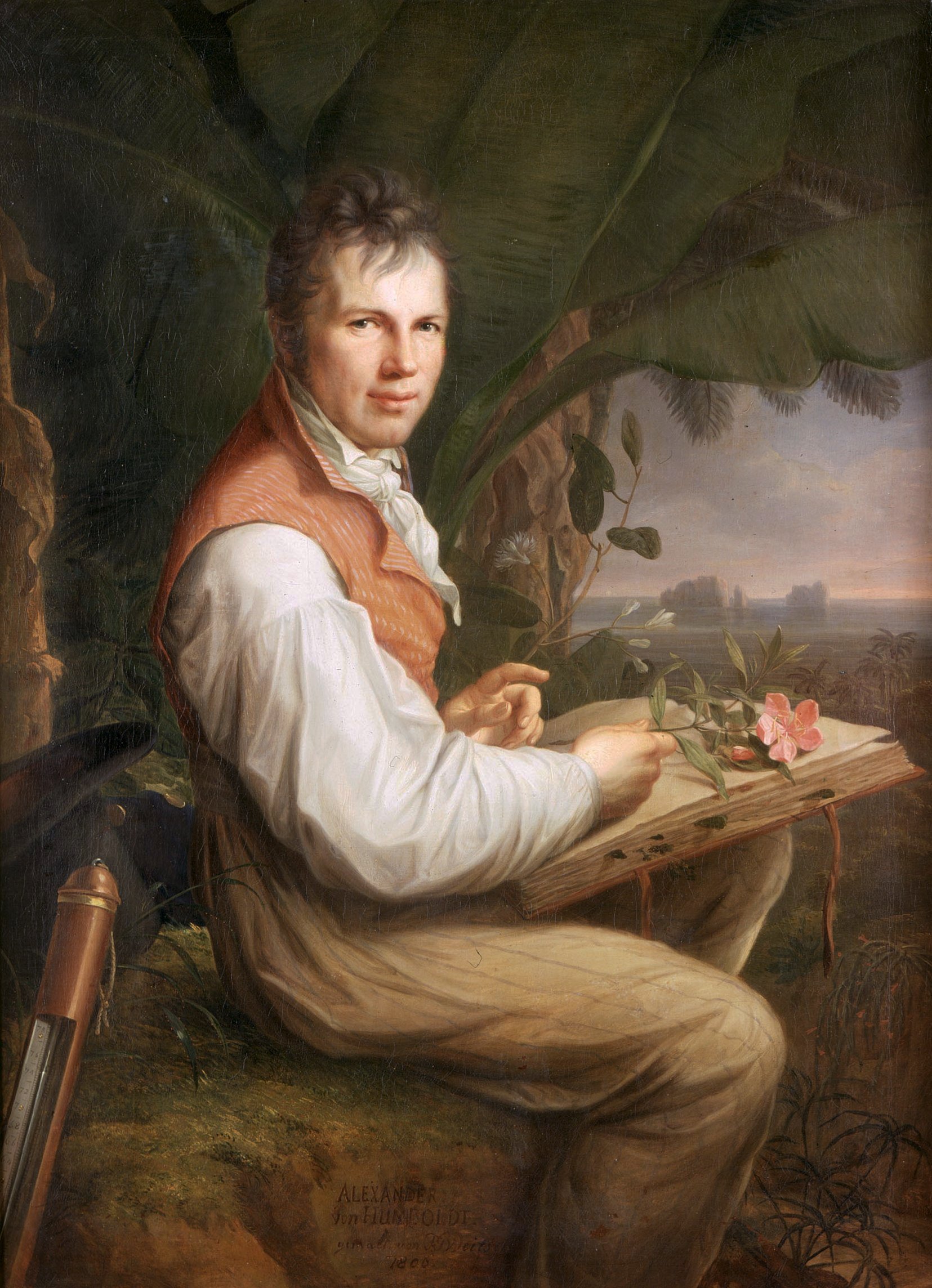

Alexander von Humboldt is best remembered as an extraordinarily driven and omnivorously curious Prussian naturalist, whose radical ideas and prolific writings made him arguably the most important natural philosopher of the 19th century. Today, more than 300 plant species are named for him. Open a terrestrial atlas and you will find features named for Humboldt on every continent; open a celestial atlas and you will find his name attached to two asteroids and to a lunar mare (the Mare Humboldtianum) on Earth’s moon.

At first glance, Humboldt would not seem to have much relevance for American art and culture. But Humboldt understood the deep connections between his passion for science and the aesthetic gratification he derived from nature. He traveled with more than 40 scientific instruments; among them was a cyanometer, an invention designed to determine which of 52 shades of blue accurately matched the color of the sky as seen at different altitudes. He believed that artists needed to know enough natural history to render their sketches and paintings with great accuracy and that scientists needed to embrace an aesthetic appreciation for the natural world. In the second volume of his magnum opus, Cosmos, he spent a third of the narrative giving advice to landscape painters, drawing on historical examples of the genre while encouraging artists to seek subjects beyond the familiar Mediterranean region. He believed that the awe-inspiring features of the hemispheric American landscape were worthy corollaries to their European counterparts and to the man-made wonders of the Old World.

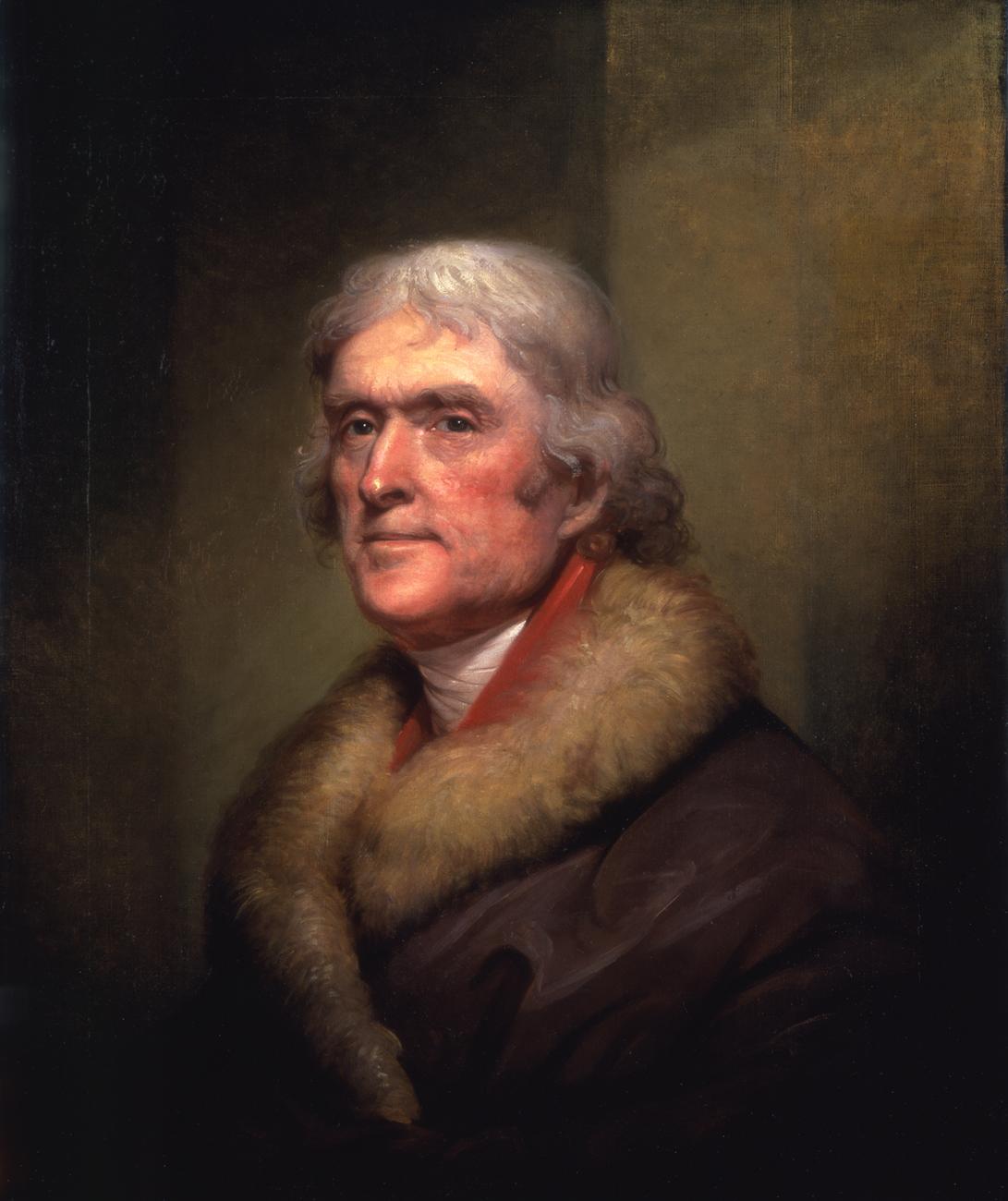

Alexander von Humboldt’s six-week visit to the United States between late May and early July of 1804 led to downstream consequences for the next 50 years, underscoring American art as a way of understanding the roots of this country’s deep cultural identification with nature. Humboldt’s primary goal during his trip was to meet Thomas Jefferson, then president of the United States, to share ideas with a man he suspected was his intellectual equal. His interest in the United States reflected his fervent desire to see its democratic style of government flourish, to extend his South American explorations into the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, and to harness North American data in his emerging picture of the world’s ecosystems.

Humboldt’s brief stay in Philadelphia and Washington came at exactly the right moment to articulate the scientific and cultural promise of the United States. “This country that stretches to the west of the

Jefferson had marshaled considerable data of his own to refute this theory in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, published first in French in 1785 and an American edition three years later. Humboldt had read Jefferson’s book and, after seeing for himself the impressive topography of New Spain, along with its rich biodiversity and sophisticated pre-Columbian artifacts, he joined Jefferson in articulating a very different assessment of New World cultures. By seeing virtue in the distinctive features of the country’s landscape and its inhabitants, he sped the United States along the path of deploying nature—and by extension landscape painting—as a core component of its cultural identity.

Read more about Jefferson's debate with European natural scientists

in “A Moose for the Misinformed: Jefferson and Natural History,” by Mark Coburn

Proclaiming himself “half an American,” Humboldt’s influence on the United States was immediate, sustained, and profound. For more than 50 years, when an American invoked Humboldt, it was to call on an unimpeachable authority on virtually any subject. Although his primary reputation rested on the ideas he developed from his scientific travels and experiments, Humboldt embraced the United States for more than its potential to enhance scientific knowledge. Humboldt envisioned the United States as an instruction manual for democracy, modeling its founding ideals for the rest of the world. His encouragement extended to the broader liberal arts and into American politics.

WHY HUMBOLDT?

Who was Alexander von Humboldt? Why and how did his life affect the United States to such a great extent? Despite the enormity of his influence during the nineteenth century, Humboldt’s name and reputation faded in the United States after his death in 1859. Many of his new ideas simply became an accepted part of what we know about this planet; others were superseded by his colleagues and successors.

However, between the 1820s and 1850s he had become one of the best known and widely admired public figures in the world. He lived into his ninetieth year, traveled on four continents, wrote more than 36 books and 25,000 letters to a network of correspondents around the globe. He had an infectious personality and boundless curiosity, surrounded himself with some of

Charismatic, annoying, exuberant, caustic, but undeniably relevant, he straddled the Enlightenment penchant for wanting to know everything about everything and the establishment of modern scientific methods designed to query that accrued knowledge. He claimed to sleep only four hours a night and called coffee “concentrated sunbeams.”

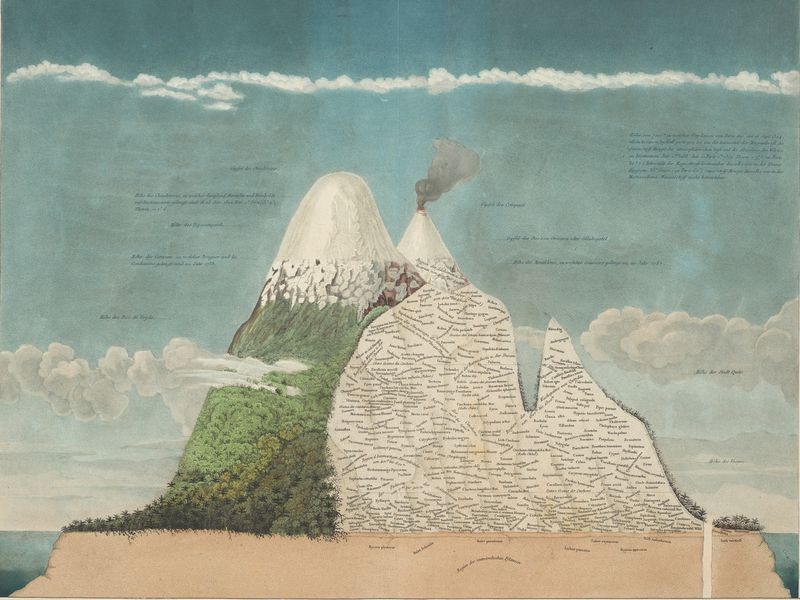

Among his many scientific achievements, Humboldt theorized the spreading of the continental landmasses through plate tectonics, mapped the distribution of plants on three continents, and charted the way air and water move to create bands of climate at different latitudes and altitudes. He tracked what became known as the Humboldt Current in the Pacific Ocean and created what he called isotherms to chart mean temperatures around the globe. He observed the relationship between deforestation and changes in local climate, located the magnetic equator, and found in the geological strata fossil remains of both plants and animals that he understood to be precursors to modern life forms, acknowledging extinction before many others. Over the course of his adult life he developed a revolutionary theory that all aspects of the planet, from the outer atmosphere to the bottom of the oceans, were interconnected — a theory he called the “unity of nature.”

It is hard to overstate how radical an idea this was in its day. After spending more than thirty years amassing data and testing ideas, Humboldt delivered a series of lectures in Berlin in 1827, describing theories that electrified his audience. From these lectures, he began drafting the book that would cement his lasting significance, as he described to his close friend, Varnhagen von Ense, in 1834:

Humboldt’s singular text grew to fill five volumes, which were written in the last decade of his life to summarize all that he had learned in his

Some of the brightest minds and prominent scientific thinkers of the era embraced Humboldt’s expansive thinking: inspired by Humboldt’s early publications, Charles Lyell drew confidence in outlining his Principles of Geology; Charles Darwin idolized Humboldt, whose encouragement contributed to Darwin’s developing theories regarding the evolution of species. Humboldt’s friend Goethe proclaimed that he learned more from an hour in Humboldt’s company than he did spending eight days reading other books.

For Humboldt’s U.S. audience, it was his travel narratives rather than his scientific monographs that ignited the imagination. Before Cosmos, Humboldt had published 34 other volumes, all sharing an evolving articulation of his underlying premise of the unity of nature. His Essay on the Geography of Plants was published in 1805, followed by Aspects of Nature in 1808. His seven-volume Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, during the years 1799–1804, is a compendium of his travels through the Americas. In 1826 he published the Essai politique sur l’île de Cuba (Political Essay on the Island of Cuba) and, after that, several books stemming from his 1829 trip across Russia. On top of that, interspersed with these travel volumes he produced separate monographs devoted to astronomy, botany, geology, mineralogy, and zoology.

Humboldt’s innate curiosity and restless intellect were shaped by his early training with some of the best minds in Europe, including his mentors, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and Christoph Daniel Ebeling, and explorer Georg Forster. When Humboldt traveled to England with Forster in 1790, he met a young chemist named James Smithson, who became another part of Humboldt’s expanding network and, later in his life, was the founding benefactor of what became the Smithsonian Institution. It was Forster, who had sailed with Captain Cook on his second voyage, who inspired Humboldt to travel widely and pursue evidence to support his unity of nature idea.

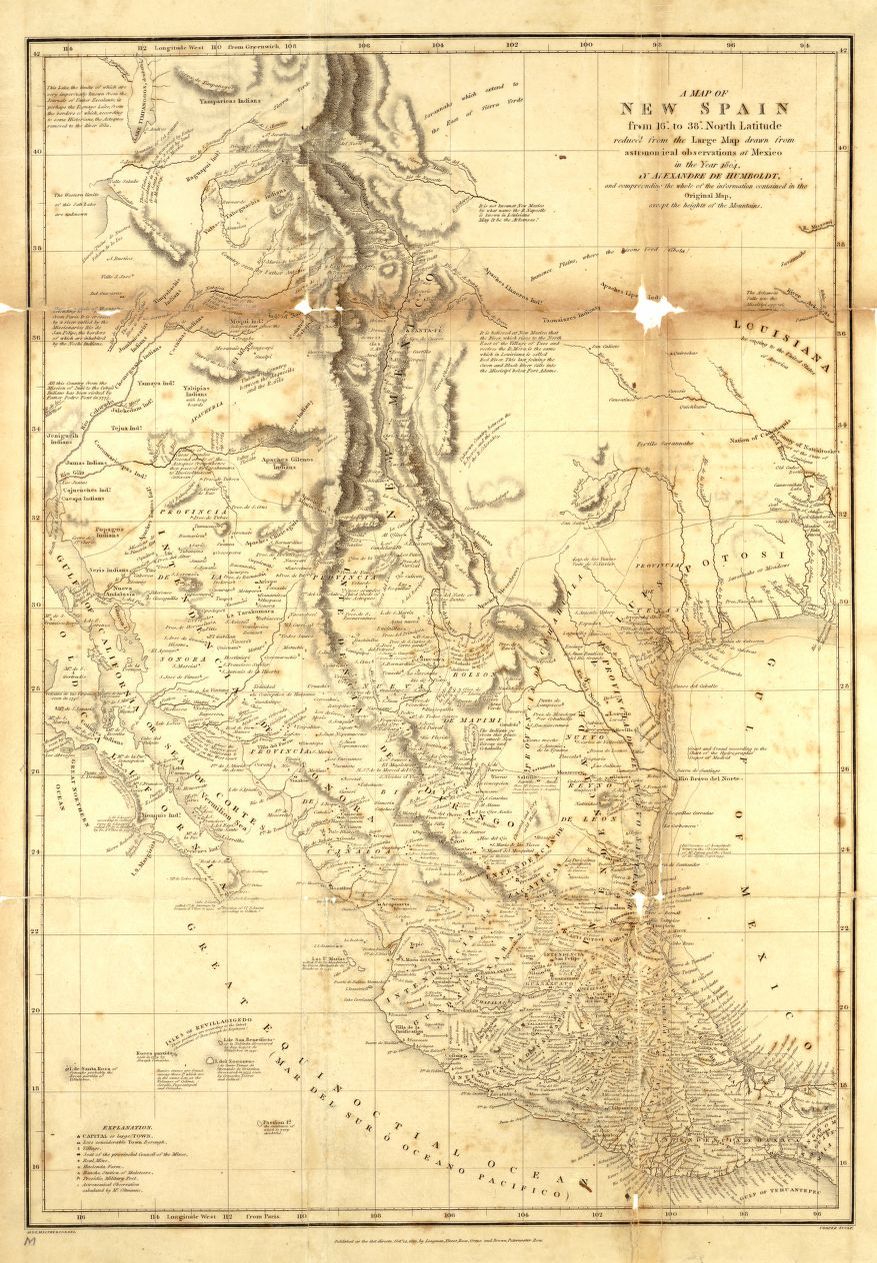

Humboldt spent five years traveling across South America, Mexico, and Cuba between 1799 and 1804. Along the way Humboldt did more than gather plant specimens and artifacts; he witnessed the Transit of Mercury and discovered the location of the magnetic equator. That signature measurement allowed him to recalibrate his equipment and take the most accurate readings to that point of longitude and latitude in the Americas.

Humboldt’s trip corrected the location of numerous cities across South America and Mexico, literally recalibrating American cartography. On top of that, he constructed the most detailed map of central North America, extending north from Mexico to the Canadian border. Sharing that map with Jefferson may have been the single most significant contribution Humboldt made to American geopolitics.

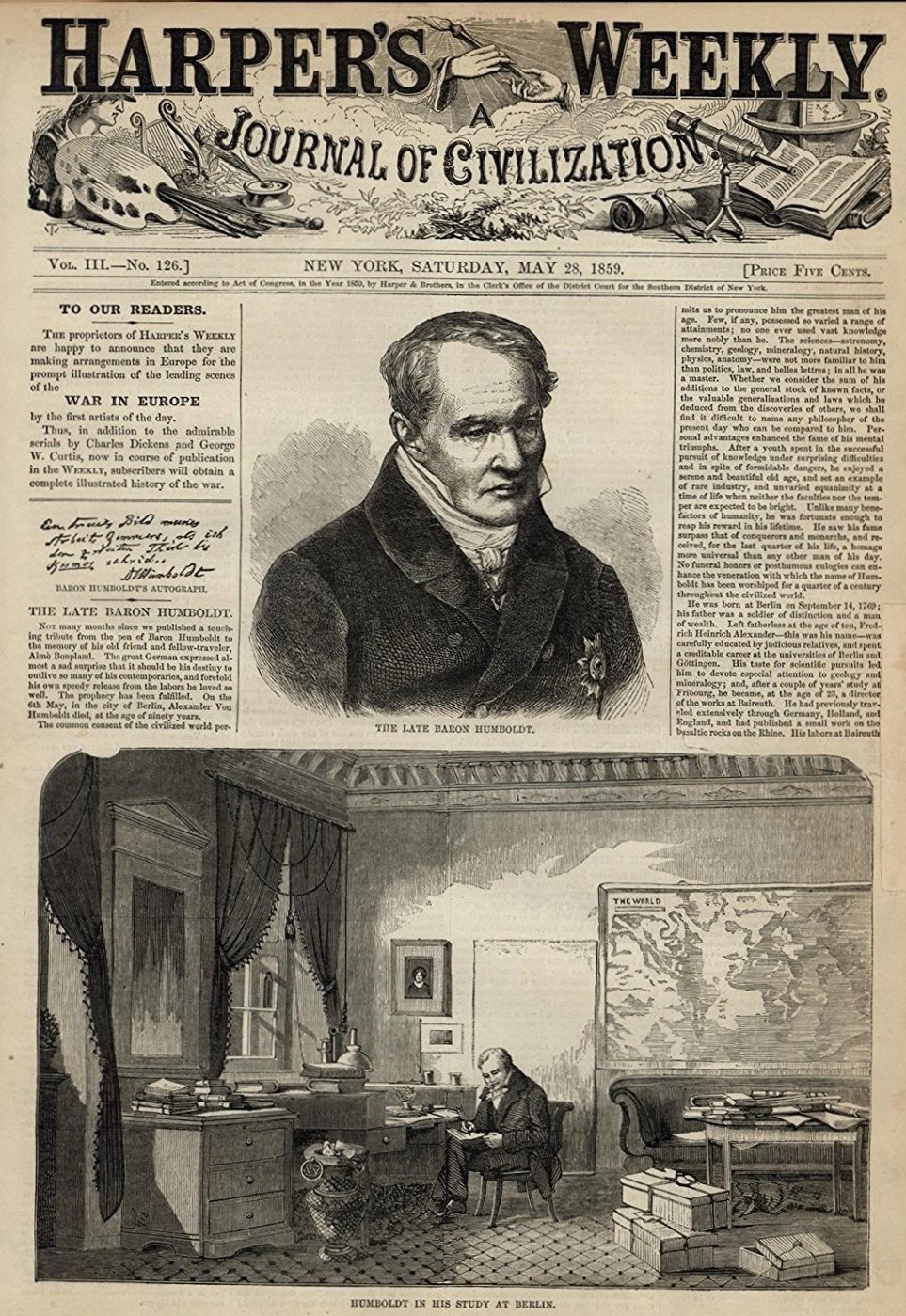

One measure of Humboldt’s deep impact in the United States is the outpouring of grief when news of the eminent naturalist’s death spread across the globe in 1859. In the United States, the New York Times and Harper’s Weekly devoted their entire front pages to his eulogy, enumerating Humboldt’s achievements, extolling his significance, and amplifying the emotional response to news of his death.

Ten years later, in 1869 — the centennial of Humboldt’s birth — the world again gave itself over to celebrating Humboldt’s name and reputation and remarking on the progress others had made standing on his broad shoulders. Once again Humboldt dominated the front page of American newspapers. The New York Times devoted extensive coverage to what was being called the “Humboldt celebration.” In Boston, Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, perhaps the leading scientist of his generation and a Humboldt protégé, delivered a heartfelt address and choreographed a program of eulogies and inspirational speeches by the leading authors and scientists of the day. It was clear, both in 1859 and in 1869, that this country owed much to Humboldt’s curiosity, writings, support, and international networks of influential people.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, who spent more than 30 years reading Humboldt, was among the speakers at the 1869 Boston celebration. In his description, we get a sense of how even Emerson struggled to express the magnitude of Humboldt’s accomplishments:

Emerson set the tone for the continued appreciation of Humboldt, eliding Cosmos with its author as he spoke of the overwhelming importance of the man and his signature accomplishment.

CHANNELING HUMBOLDT IN THE UNITED STATES

Humboldt’s brief stay in the United States in 1804 established the foundation of his extensive network of friends and admirers there. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had just embarked on their exploration of the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase, and Jefferson was in the midst of contentious international negotiations with France and Spain over the new southern and western borders of the United States. Humboldt arrived with maps and statistics that helped Jefferson and his cabinet think strategically about those negotiations. The Prussian traveler’s effusive personality and unbounded curiosity about American geography, culture, and politics sparked lifelong friendships with some of the key figures of American history.

Beyond politics, Humboldt inspired artist Charles Willson Peale to resume his dormant painting career to paint Humboldt’s portrait for his museum. In Philadelphia he was feted by the scientific community. His early publications already graced the shelves of the library of the American Philosophical Society, which made him a member. However, it was after this visit that Humboldt would become a force of nature himself. For the remaining fifty years of his life, people in the United States became part of Humboldt’s global network of friends, allies, and scientific partners.

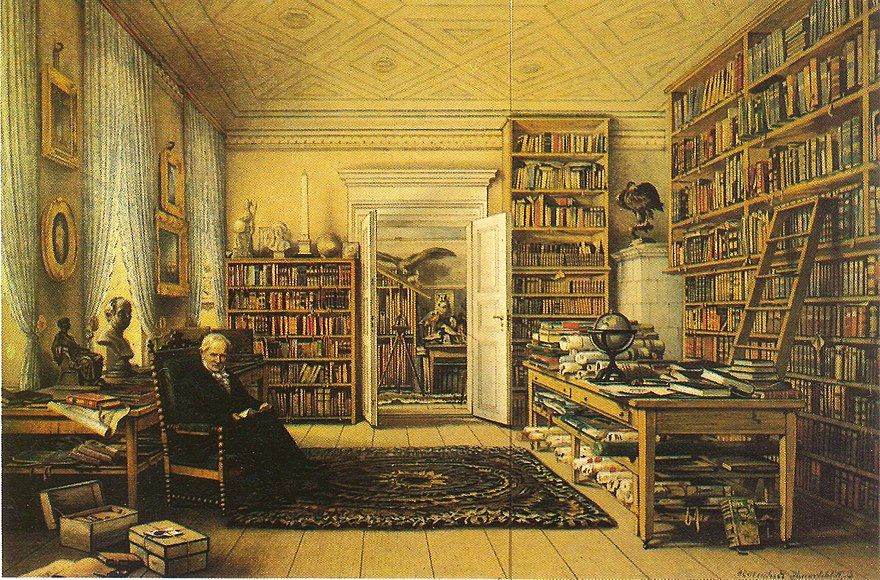

Those alliances helped define the nation; America’s presence on the international stage shone brighter with Humboldt’s approbation, an imprimatur many in the United States assiduously cultivated. Humboldt’s lectures and books established his reputation as a leading mind in the natural sciences. His eagerness to absorb the new information from the United States added another dimension to American exploration. American explorers knew their maps, measurements, statistics, and expedition narratives would make their way into his hands. Updated maps and illustrated books were the lingua franca of expedition reports. Each American contribution to this international enterprise found its way into Humboldt’s growing library, and details from them appeared in the Prussian baron’s works.

Further, Humboldt encouraged the addition of artists as members of those expeditions. In particular, Stephen Harriman Long and John C. Frémont conducted expeditions using Humboldt’s ideas and books as their inspiration. The published report from the Long Expedition later served as a foundation for literary descriptions of the American interior that would in turn become an important aspect of the Hudson River school landscape aesthetic. Frémont’s narratives helped create his persona as the Pathfinder and earned him the appellation among explorers of “the American Humboldt.” During the nineteenth century, the scientific journey became an epistolary venture in which distance became a metaphor for reach.

Humboldt had always intended to return to the United States, but each successive venture he undertook and each new volume he published delayed and ultimately defeated that goal. Thus Humboldt cultivated proxies — explorers who traveled to the United States in his stead and with his support. The information assembled from these journeys flowed directly to Humboldt — population statistics, ethnographic information and artifacts, natural history specimens, and cartographic measurements.

All of this was designed to fill the gaps in his increasingly comprehensive understanding of landforms; the global distribution of plants, animals, and people; and how climate operated as a force on everything. This path to the increase and diffusion of knowledge — something of a buzzword during the Enlightenment — was navigated through lavishly illustrated publications. The market for these books crested with the wave of popularity experienced by Humboldt as he wrote, illustrated, and published volume after volume based on his five years in the Americas — an enterprise that ruined him financially but contributed to his global fame.

Humboldt believed that the New World should not be measured using the standard of architectural wonders found in the Old World. Europeans looked to the built environment—like cathedrals and universities— as evidence of cultural significance. As such, they saw the Americas as continents devoid of history. Instead Humboldt argued, “Nature herself is sublimely eloquent,” applying aesthetic theory and vocabulary to descriptions of the natural monuments boasted by the New World. His embrace of nature as an impressive attribute symbolic of cultural prowess encouraged the development of a wilderness aesthetic in the United States.

As early as the 1780s the nascent United States of America had tentatively adopted a nature-inflected sense of identity thanks to Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, which was read widely in French and English among the literary and scientific elite on two continents. In this slim volume, Jefferson enumerated the myriad ways American geography, agriculture, commerce, and people were in no way inferior to their European counterparts. His narrative and statistics refuted the statements made by the influential European naturalist George-Louis Leclerc, the comte de Buffon, that all aspects of the New World were smaller, weaker, and more degenerate than their European counterparts. The discovery of the bones of mastodons— at that time recognized as the largest terrestrial creature known on the planet—in present-day Kentucky and upstate New York seemed further proof that Buffon’s theories were at best false and pernicious.

Jefferson’s book staked out the position that America’s cultural prospects were tied to the awe-inspiring scale and uniqueness of the very things found within its borders. He further argued that features like Virginia’s Natural Bridge and New York’s Niagara Falls were evidence of American geographic superiority. In doing so, he laid a foundation for erecting a cultural identity grounded

If Humboldt’s books were guides to the New World, he was one of the principal destinations for travelers to the Old World. Following the War of 1812, the vogue for visiting Humboldt in Europe grew. He became the center of an interconnected web of correspondents, colleagues, and admirers, many of whom were Americans. From his perch in Paris, Humboldt played a central role in French scientific societies. With each publication, the world took greater notice of Humboldt’s ideas. By the 1820s Humboldt’s words and images became an integral part of the American school curriculum, and lengthy excerpts from his books appeared frequently in the leading literary and scientific journals. The litany of American luminaries who beat a path to his door is an astounding array of politicians, statesmen, authors, intellectuals, artists, and scientists.

Here we encounter Humboldt, “half an American” by his own reckoning, as a man who admired and espoused American ideals. In Paris, Humboldt and the Marquis de Lafayette stood at the center of a group of liberal thinkers who supported the United States and welcomed American travelers. Both men saw in American democracy a template for saving Europe from monarchical and dictatorial ruin. Humboldt’s liberal politics and outspoken support of America endeared him to this country while placing him at odds with the French emperor.

The mutual dislike between Humboldt and Napoleon serves as a framework for understanding how and why Humboldt sought faster and more reliable networks of communication across Paris, the continent, and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean. He befriended Americans who were able to enhance the establishment of those relays. Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Samuel F. B. Morse formed part of that network. Humboldt’s eagerness to advocate for Morse’s telegraph and subsequently, the laying of the transatlantic cable, spoke to his desire to be in contact with his allies and advocates instantaneously and without Napoleonic interference. For Humboldt, knowledge was intended to be shared— disseminated as

Humboldt’s advocacy for the United States was not uncritical. He held an unequivocal stance on the one issue on which he and the United States parted ways: American slavery. An adamant believer in racial equality, Humboldt railed against colonial rule and enslavement. He associated nature with an inherent right to individual freedom for all humankind, and he believed societies and governments must protect that right. Although he sidestepped engaging directly with Jefferson on the issue, he spared little anger in his correspondence with those in his close circle. As early as 1825 he feared that the perpetuation of slavery in the United States would be the country’s undoing, prescient thoughts that he shared with many in his American network.

Humboldt’s fervent desire to see America as an exemplar of a true democracy kept him close to this country’s leading figures but simultaneously left him frustrated at his inability to gain traction on this most important issue. That engagement with American politics peaked with Humboldt’s vocal support for John C. Frémont’s 1856 presidential campaign as the first Republican candidate, running on an abolitionist platform inspired by Humboldt. Frémont had conducted five of his own expeditions into the American West, displaying his admiration for Humboldt by naming as many landscape features for the explorer as he could. Frémont also played a role in California politics during the final push toward statehood. California unexpectedly entered the Union in 1850 as a free state, and the California landscape—notably that of Yosemite—became the emblem for the promise of liberty in a nation soon plunged into civil war.

Before he had left the United States, Humbolt also expressed concern for the cultural well-being of America’s native populations, quizzing Jefferson on his relationship with the various nations. Humboldt’s travels in South America had convinced him that the indigenous people he encountered were descendants of advanced civilizations destroyed by generations of Spanish colonial rule.

Democracy, in Humboldt’s mind, should extend to all inhabitants of a nation, regardless of race or standing. Humboldt’s increased concern following President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830 fueled his interest in fellow Prussian naturalist Prince Maximilian zu Wied’s trip to the United States from 1832 to 1834 with artist Karl Bodmer. Prince Max, as he was often called, had trained with Humboldt’s professors at Göttingen. Inspired by Humboldt, he spent two years in Brazil writing a highly acclaimed ethnography of the Botocudo (Aimoré) tribe. Prince Max and Bodmer’s journey through the United States provided

The publication of Cosmos made Alexander von Humboldt perhaps the best known public intellectual figure anywhere on the globe. In the United States Cosmos inspired Frederic Church’s enthusiastic embrace of science and art, Emerson’s seminal essay Nature, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, and Walt Whitman’s poetic self-portrait in Leaves of Grass. During the 1850s there was a conscious effort on the part of these men to frame Humboldt as a distant mentor.

Humboldt’s ideas inflected every aspect of Church’s artistic production, including subjects far removed from the artist’s South American subject matter. Church gladly embraced the opportunity to adopt a Humboldtian mantle for his artistic persona. In so doing he reaffirmed the significance of landscape painting as the genre most capable of conveying America’s cultural ambitions.

THE ABSORPTION OF HUMBOLDT

American explorers across Humboldt’s lifetime repaid his generosity in sharing his map and information with Jefferson — through the dissemination of maps, journals, published reports, and visual images. The movement of ideas and data from Humboldt out through his network of correspondents — and the return of new information to Humboldt, feeding his hunger for knowledge and the development of new theories — was a collaborative and reciprocal system. In his 1869 eulogy, Emerson remarked that where Humboldt walked, an entire scientific academy marched in his shoes.

It was an apt metaphor, for Humboldt traveled across four continents and an ocean in search of the experiences and measurements that would anchor his ideas. He seemed happiest when he was working in the company of talented colleagues, remarking to fellow scientist Joseph Gay-Lussac that he did his best work when surrounded by those who were doing better work than he.

Humboldt’s willingness to distribute his massive collection of field specimens to a network of trusted colleagues demonstrated his genuine passion for sharing knowledge and his pragmatic acceptance that alone he would not have the time to do all of the research himself. Humboldt spent his lifetime increasing knowledge, and as that knowledge diffused, so too did the connection to his name. During the nineteenth century, towns, counties, and streets across the United States bore his name; in the decade following his death,

Louis Agassiz noted in 1869 that Humboldt’s name was invoked less and less as the years passed, though his ideas continued to circulate widely. In his centennial address he remarked that every school child in America had been taught by Humboldt without ever knowing their teacher’s name. Ticking off a litany of areas in which Humboldt had revolutionized our understanding of the planet, Agassiz noted how others had been inspired by his writings to further investigate his observations. As the once unified field of “natural philosophy” branched into the full canopy of the individual physical and biological sciences, Humboldt was not claimed by any one discipline. Instead his work formed a foundation layer on which his friends, rivals, colleagues, and successors built the modern edifices of scientific inquiry and learning.

Although Humboldt’s name and reputation was eclipsed in the United States, he was not forgotten elsewhere. He remains to this day a revered figure in South America, remembered for his friendship with Simón Bolívar, the Liberator. He is credited with inspiring the young revolutionary to return from Europe to free his homeland from Spanish rule.

In Mexico, Humboldt was granted honorary citizenship for his contributions to the archaeological rediscovery and appreciation of pre-Columbian civilizations. In Germany he and his equally famous brother, Wilhelm, were honored by conferring their name upon what is now Humboldt University in Berlin.

In the United States, although Humboldt’s name had vanished, his ideas did not. When Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring in 1962, her argument for saving the American bald eagle by banning the use of DDT drew on the same logic of interrelated downstream consequences Humboldt had postulated regarding local human-induced climate change at Lake Valencia in Venezuela in 1800.

With the rise of the environmental and conservation movements of the twentieth century, Humboldt’s ideas have gained renewed traction and gradually his name has become re-associated with those once radical ideas of planetary interconnectedness and the emergence of climate science in this era that some have designated as the Anthropocene. Alexander von Humboldt is experiencing a renaissance with this rise in eco-awareness, visible in contemporary fine arts practice as well as across the sciences, as befits his own broad reach.