Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

Editor’s Note: Bruce Watson is a Senior Editor of American Heritage and writes a popular history blog at The Attic. He is the author of six books of history and biography.

Last week, the governor of Illinois activated the National Guard to protect the state capitol a few blocks from where Abraham Lincoln spoke. Similar sights — armed guardsmen outside capitol buildings — greeted Americans across the country and in the Nation’s Capital.

But no government “of the people, by the people” can be held together by guardsmen or police. As Lincoln taught us, the sole guardian of democracy is “the people.”

On a late fall day in 1837, hundreds of howling men with blazing torches surrounded a warehouse as darkness fell in Alton, Illinois, a small town on the Mississippi across from St. Louis. Inside sits their target — the printing press of Elijah Lovejoy. a Presbyterian minister and abolitionist.

This is not Lovejoy’s first encounter with a mob. Three times his presses, guilty only of printing attacks on slavery, have been thrown into the Mississippi. Now another mob. . .

Someone puts a ladder up. A boy climbs to set the warehouse roof on fire. Lovejoy emerges, topples the ladder, retreats.

But when the ladder goes up again, he steps into the crossfire. The murder, says John Quincy Adams later, “is a shock as of an earthquake to this country.”

Weeks later, on a wintry Saturday evening, a tall, skinny man rises to speak before the Springfield Lyceum. The Lyceum has one rule for speakers — no politics. But mobs, regardless of their cause, are not “politics by other means.” Mobs, the speaker knows, are the opposite of politics. His topic: “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions.”

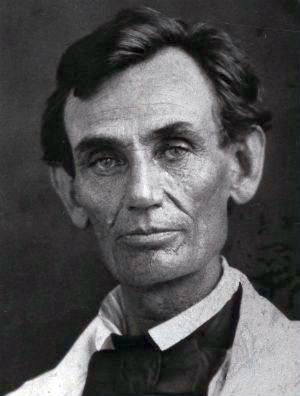

Few in the audience know him. A recent arrival in Springfield, Abraham Lincoln is a “prairie lawyer,” riding horseback to try cases throughout central Illinois. Awkward and ungainly, he also has, a friend says, “a gloomy and melancholy face,” a face etched with loss. At 28, he has already buried his mother, infant brother, sister, and first love.

“In the great journal of things happening under the sun, we, the American People. . . find ourselves in the peaceful possession of the fairest portion of the earth.” We did not earn this blessing, Lincoln continues. Our democracy is an inheritance, and our task is preservation.

“How then shall we perform it? At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall