Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2021 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2021 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Editor’s Note: David Michaelis is the author of seven books, including the bestselling biography, N. C. Wyeth. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent monumental biography, Eleanor, the first one-volume biography in six decades of the longest-serving First Lady.

Eleanor Roosevelt always wanted things to happen faster.

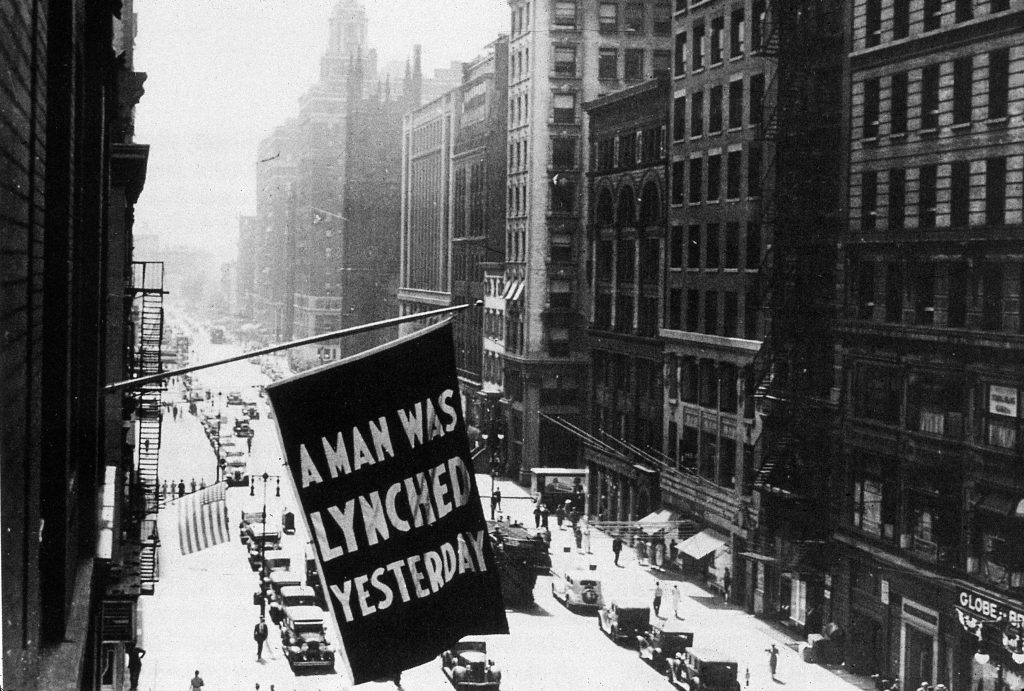

In 1934, her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, wouldn’t take a stand on anti-lynching legislation. The Democratic Party, with many conservative Dixiecrats in positions of power, was ducking any issue that confronted African American segregation or injustice. So Eleanor felt it became her duty to respond, beginning with questions of discrimination in New Deal relief programs.

Eleanor had not recognized the depth of institutional racism during the New Deal until she became involved with the Subsistence Homesteads Division, an agency intended to help the unemployed return to farming. When she urged the agency to admit African Americans to Arthurdale, an experimental West Virginia community created a year before to provide opportunities for local miners and farmers, her intervention failed – as had every appeal she made to FDR to deal with the country’s terror crisis and champion anti-lynching legislation.

Joining the DC chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Eleanor made common cause with the national executive secretary, Walter White, the one determined crusader for racial justice in New Deal Washington. She now invited White, Clarence Pickett of the American Friends Service, and the presidents of six African American universities to the White House to discuss the Arthurdale situation.

At eight in the evening on Friday, January 26, 1934, Eleanor opened the problem of race in the homesteads to the group. One of the educators, Robert Russa Moton, a Virginia-born son of former slaves and the president of the Tuskegee Institute, had been the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, where he had been kept apart from the other speakers and made to sit alone. Five years later, Moton, a lifelong advocate of accommodation in race relations, made a deal and supported Herbert Hoover, Coolidge’s secretary of commerce, then receiving highest praise for his handling of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which had cost more than half a million blacks their homes.

Hoover won the traditionally Republican black vote in 1928, but as soon as the Great Engineer had claimed his prize, he refused even to acknowledge Moton. Blacks turned on Hoover in