Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 7

Editor’s Note: Fergus M. Bordewich has written eight books of history. Portions of this essay were adapted by the author from his most recent book, Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America.

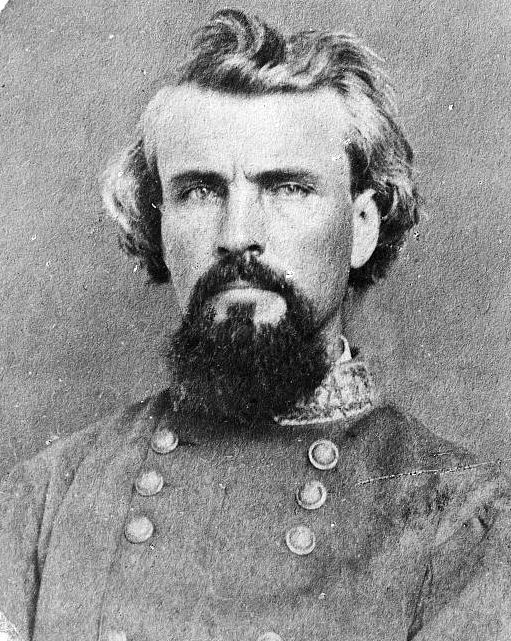

On April 12, 1864, a hard-riding Confederate force of between 1500 and 2000 cavalry under General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a wealthy prewar slave trader and the South’s most enterprising and skillful cavalry commander, surprised the garrison of Fort Pillow, 40 miles north of Memphis.

Forrest, goateed and gimlet-eyed, was known to Confederates and Federals alike for bold strikes and a knack for seizing decisive victories against overwhelming numbers of the enemy. At Fort Pillow, however, numbers were on Forrest’s side. The attack came at the climax of a daring raid that had taken Forrest’s men deep inside Union lines through Tennessee and Kentucky as far as Paducah, close enough to Illinois to stir panic north of the Ohio River.

Fort Pillow was a complex of earthworks and gun emplacements sprawling along bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, on the western edge of Tennessee across from Arkansas. Built by the Confederates in 1861, it was captured by the Union the following year. Its river-facing defenses were formidable, but the handful of poorly situated field guns and howitzers that were meant to protect the landward side overlooked a maze of deep gulches that blocked the defenders’ view. The garrison included a total of about 550 men from two black artillery units, and a white Unionist regiment of Tennessee Cavalry.

Forrest, whose reputation for ruthlessness preceded him, warned the defenders that he wouldn’t be responsible for what happened to them unless they surrendered immediately. Then, under the cover of a white flag, he infiltrated men through the gulches until they were immediately beneath the fort.

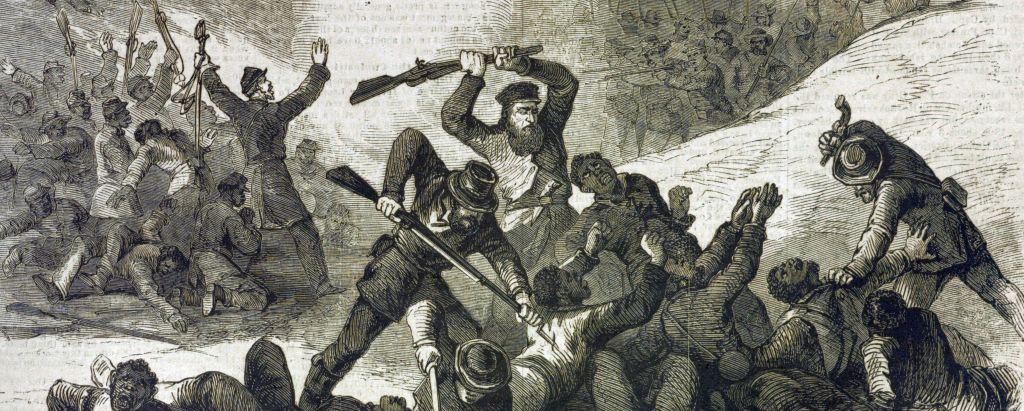

The attack was ferocious, the defense chaotic. The broken land made it difficult, and soon impossible, for men from one part of the garrison to help those who were overrun. A sniper’s bullet killed the fort’s commander, and the white Tennesseans broke and fled. Most of the blacks resisted spiritedly until they were overwhelmed. The end was swift and horrific.

Forrest’s Confederates cried, “No quarter!” and “Black flag!” — that is, take no prisoners. Soldiers, whites as well as blacks, who tried to surrender were shot, hacked with sabers, and beaten to death with rifle butts. Wounded men were murdered where they lay. Several were burned to death in huts. Others were thrown into pits with the dead and buried alive. Fleeing men slid, fell, and jumped over the edge