Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Editor’s Note: Justin Martin is the author of five books, including A Fierce Glory: Antietam —The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery, from which he adapted this essay.

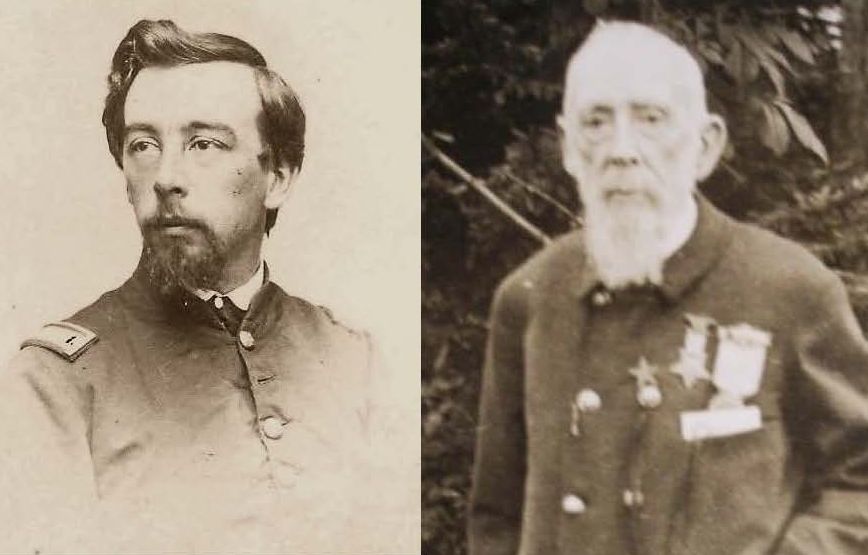

John Mead Gould spent a single day at Antietam. The battle consumed him for the rest of his life.

On September 17, 1862, Gould fought on the Union side as a lieutenant with the 10th Maine. Pandemonium reigned in the close confines of the Western Maryland valley where the battle took place.

So many soldiers fired so many weapons with such urgency that the field was soon thickly shrouded in smoke, and the air swam with projectiles, seemingly coming from all directions.

The sheer volume of noise was overwhelming. Cannon rumbled; bullets zinged. There were the shrieks of falling men, the whinnies of falling horses.

Antietam was more intense by far than anything Lt. Gould had ever experienced. It would continue to hold that grim distinction, though he’d fight in many subsequent battles until the end of the Civil War. Antietam was simply different from other contests: more heated, more savage, more consequential.

The battle occurred during an especially demoralizing stretch for the Union, filled with military losses, one coming fast on another. The Confederacy had grown increasingly bold, to the point of marauding into Maryland.

This was the war’s first Southern incursion into Northern territory. Achieve victory here, and the Rebel army could storm across Union territory and strike who-knows-where — Philadelphia, Baltimore, even Washington, D.C. No place would be safe. “Jeff Davis will proclaim himself Pres’t of the U.S.,” wrote a panicked New Yorker. “…The last days of the Republic are near.”

Even if an attack on a major city didn’t immediately follow, a Confederate victory promised to spark a political disaster. The Southern plan was to sow chaos and more chaos, and some of the ploys were remarkably subtle. For example, a Union loss at Antietam might prompt skittish Northerners to vote Lincoln’s Republican party out of Congress. In would sweep the Democrats, a politically conservative party at the time that might be more amenable to a negotiated settlement of the war. Perhaps a Democrat-controlled Congress would bypass Lincoln, recognizing the Confederacy’s independence.

Or maybe the states that had seceded would be invited to re-enter the Union with slavery