Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Editor's Note: David S. Brown teaches history at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. He is the author of The First Populist: The Defiant Life of Andrew Jackson, from which this essay was adapted.

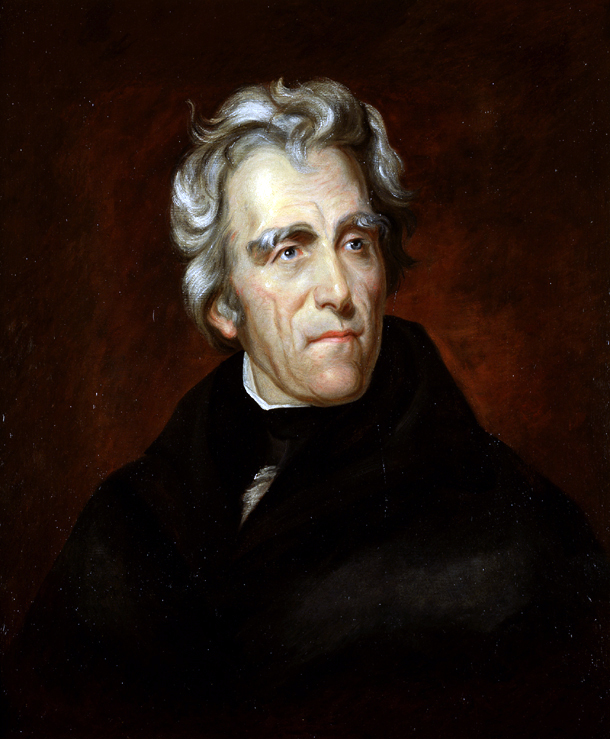

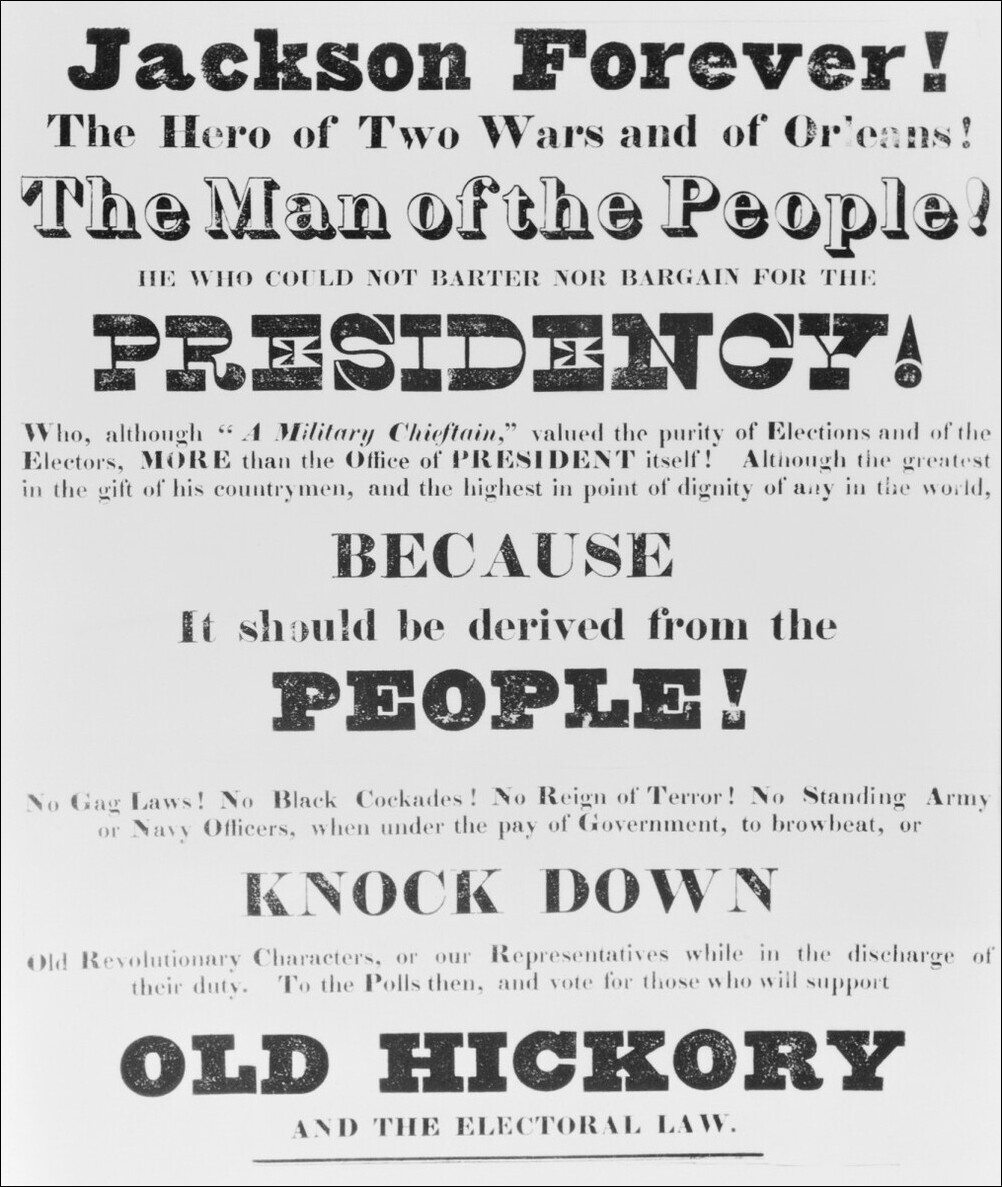

Andrew Jackson, the first president to be born in a log cabin, to live beyond the Appalachians, and to rule, so he swore, in the name of the people, refuses to fade away. Controversial in his own day, he remains unrepentant.

Some identify Jackson as the common man’s crusader in chief, a defender of farmers and wage-earners who, with a single lethal veto, is said to have saved the republic from a rapacious Money Power by quashing a government-chartered national bank that catered to economic elites. Others are far less willing to accept as a hero a slaveholder, an architect of Indian removal, and a critic of abolitionism. The epithets “racist,” “white nationalist,” and “ethnic cleansing” now vie with the Bank War and the Battle of New Orleans in reckoning with Jackson’s fluctuating reputation.

On one point, however, all sides can perhaps agree—Old Hickory, the first president to come from neither Virginia nor Massachusetts, broke up the long train of coastal executive aristocrats, embodying in his improbable ascent the promise of western frontier peoples negotiating a natal age of expanding political participation.

More precisely, Jackson, a cotton nabob, master to hundreds of slaves in several states, in fact straddled two sections. As the country’s fifth Southern president, he aligned as well with the interests of an entrenched squirearchy, having sought entry into its environs from an early age. The orphan of impoverished Scots-Irish immigrants, Jackson strove to ape the gentry and become a gentleman among Tennessee’s self-anointed blue bloods. Along the way, this parvenu acquired a plantation, bought and sold slaves, engaged in land speculation, and bred racehorses. He pushed for military appointment, fought in class-affirming duels, and adopted a distinctly southern notion of honor that elevated the landed nobility over mere citizens.

Two reflections on an aged Jackson by British women—the visiting writer Harriet Martineau and the expatriate actress Fanny Kemble—offer contrasting but retrospectively revealing judgments. The former depicted the general as fundamentally ill-informed and uneducated, a poorly postured eminence betrayed by a trace of depression:

Kemble more amiably emphasized the courtly, martial side of her subject, whom she described as:

Jackson, of course, cultivated both impressions. While Martineau stressed the unlettered side of her subject, Kemble, once described by the writer Henry James as having “seen everyone and known everyone . . . in two hemispheres,” noted a natural patriarch, an air still more abundantly asserted by a cotton oligarchy committed to the appearance of chivalry in the practice of slavery.

Martineau highlights the surprising frailty of Jackson through most of his life. The general’s cadaverous physique idled in pain and discomfort; his many ink-stained letters are filled with references to internal afflictions, ailing teeth, and weak lungs. But he was hardly a hypochondriac. Jackson paid with his body for the chain of military campaigns—from the American Revolution to the War of 1812 to the subduing of the southern Indians—and ritual affairs of honor that secured his reputation. He suffered from dysentery, dyspepsia, and bronchiectasis; contracted chronic diarrhea; battled pulmonary infection and malaria; and may have had intestinal parasites. Two bullets were lodged in his body - one from a duel and the other during a brawl. The cavities were prone to infection, and the lead from them leached steadily over the years into his system. Jackson bore the aches and inconveniences of these infirmities for much of his life, and they must have exacerbated his tendency to be quick-tempered.

Jackson’s splenetic cast of mood and attitude, “formidable” in Martineau’s rendering and “very obstinate” in Kemble’s, is perhaps Jackson’s defining attribute. He could be a devout and fierce hater, inspiring in turn the devout and fierce hatred of others. A series of pre-presidential episodes—ordering the deaths of deserting militiamen, killing a Tennessee dandy in a duel, and overseeing