Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Jon Meacham is a renowned presidential historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose latest books include The Soul of America and And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, from which this essay was adapted.

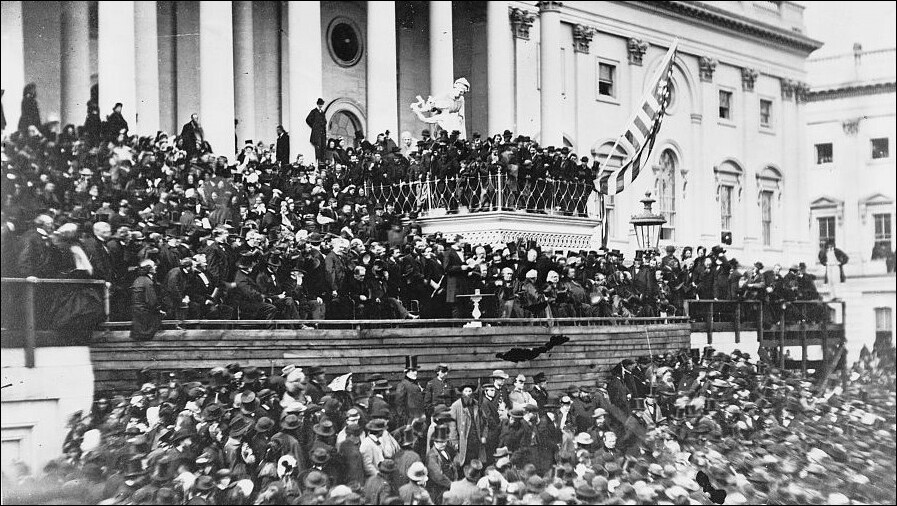

The day of Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration, gales of wind and sheets of rain roared across the Potomac and struck Washington, destroying trees and soaking the city. Pennsylvania Avenue was a sea of mud, thick and soggy. It had already been raining for two days running; the Army Corps of Engineers considered constructing pontoon bridges to make the city’s main thoroughfare passable. A foot could sink as deep as a knee in the ooze.

The wet wartime capital was at once festive and solemn. Willard’s Hotel, next door to the Treasury Building, was packed with 1,008 guests, and The Daily National Republican reported that twelve hundred inauguration-goers had swarmed the hotel’s dining tables. “The other hotels in the city were also full, not being able to accommodate another boarder,” the newspaper wrote.

What the journalist Noah Brooks, an intimate of President Lincoln’s, recalled as the “dark and dismal” weather improved slightly as the crowds slogged to the Capitol for the inaugural ceremonies. Completed in the war years, the building’s cast-iron dome loomed above Washington. The president had made sure that the project continued even as the struggle unfolded. Workers, many of them enslaved until Lincoln had signed the bill for emancipation in the District of Columbia in 1862, stayed on the job.

“It seemed a strange contradiction to see the workmen...going on with their labor,” The New York Times had written, “the click of the chisel, the stroke of the hammer” amid “the tramp of the battalions drilling in the corridors.” Lincoln understood the significance of perseverance. “If people see the Capitol going on,” he had said, “it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on.”

And it had. Now, Lincoln stood again where he had stood four years before, at the East Front of the Capitol. Hundreds of thousands of Americans who had been alive on March 4, 1861 were dead, slain by one another’s hands. Innumerable others were wounded and maimed in body and in spirit. Everything had hung in the balance since Fort Sumter. “We are now on the brink of destruction,” Lincoln had said after the late 1862 Union defeat at Fredericksburg. “It appears to me the Almighty is against us, and I can hardly see a ray of hope.”