Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

Authors: David Dean Barrett

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

Editor’s Note: David Dean Barrett is a military historian, specializing in World War II. His first book, 140 Days to Hiroshima: The Story of Japan's Last Chance to Surrender, was published in April of 2020.

By the summer of 1944, U.S. military power in the Pacific Theater had grown spectacularly. Beginning days after the D-Day invasion in France, American forces launched their largest attacks yet against the Japanese-held islands of Saipan on June 15, Guam on July 21, and Tinian on July 24. Situated 1,200 to 1,500 miles south of Japan in the crescent-shaped archipelago known as the Marianas, they were strategically important, defending the empire's vital shipping lanes from Asia and preventing increased aerial attacks on the homeland.

Over the next sixty days, each of the three islands fell to the Americans. During grueling land and sea campaigns, U.S. forces killed 60,000 Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen, while the Japanese inflicted just under 30,000 total casualties on the Americans, killing 5,500.

On June 19 and 20, west of the Marianas, the American and Japanese navies fought one of the greatest air-sea engagements of World War II, the Battle of the Philippine Sea — also known as The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. In the course of the two-day battle, American aviators decimated their Japanese counterparts, shooting down nearly four hundred aircraft. The additional destruction of three Japanese aircraft carriers forever prevented Japan from using carriers to conduct offensive operations in the war.

The losses also made clear to Japan’s military leaders that there was no chance of victory; their only remaining options would lie within the terms of peace, if the Allies were willing to negotiate. With Japan’s failed defense of the Marianas, the war journal of Imperial Headquarters concluded in July of 1944:

In the aftermath of the battles, American Seabees

The fall and early winter of 1944 saw the fall of Peleliu, six hundred miles east of Mindanao, along with the invasion of the Philippines, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which was the largest naval engagement in history, and then the relocation of the strategic bombing campaign against mainland Japan from China to the Marianas.

As 1945 opened and the war in the Pacific entered its fourth and decisive year, the United States had fought its way across the vastness of the world’s largest ocean and had begun its assault on Japanese territory, but at an ever-greater cost. From the summer of 1944 to the war’s end in August of 1945, America suffered nearly two thirds of its total Pacific War casualties, including over half of the men killed in action.

More than 70,000 men in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine divisions invaded Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945. In anticipation of the most intense ground fighting of the war — what the U.S. knew would be a fiercely determined opposition — the assault was supported by 800 ships and 220,000 naval personnel.

Located midway between the American B-29 bomber bases in the Marianas and the main islands of Japan, the tiny speck of volcanic earth was invaluable in the vast Pacific Ocean, its runways representing salvation for crippled B-29s returning from their bombing missions. Taking the island and eliminating its enemy radar station also deprived the Japanese of an early-warning system for attacks on the home islands, and eradicated the risk of any further attacks by Japanese planes against Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, as well.

In the thirty-six days of combat it took to wrest the eight-square-mile island from its 20,000-plus defenders, 19,217 Americans were wounded and a further 6,822 killed — 853 men for every square mile. Japanese losses were nearly total.

The new air offensive from the Marianas — which began in late November of 1944 — was a huge logistical improvement over the India-China operations, but it remained ineffective. To take advantage of the newest, most sophisticated, and expensive heavy bomber in America’s arsenal — the B-29 — the bombs were being dropped from over 25,000 feet during the day. The bombs were often miles off target, primarily due to the persistent existence of the jet stream and cloud cover over Japan.

Things quickly changed when, on January 20, 1945, a rising star in the United States Army Air Forces, thirty-eight-year-old Curtis LeMay, nicknamed Old Iron Pants, took control of the XXI Bomber Command headquartered at Harmon Field on Guam. A veteran of nearly two years of aerial combat with the Eighth Air Force in England, LeMay had helped develop the “combat box” formation used over Europe. The configuration protected heavy bombers against fighter attack by maximizing the defensive firepower of all the .50 caliber machine guns of the planes in the formation, while at the same time concentrating the bomb pattern on the target.

Future Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara described LeMay as “the finest combat commander of any service I came across in the war.”

Sent to the Pacific to get big results, throughout February and into the first week of March, LeMay and his staff worked on plans that radically altered the XXI’s bombing tactics. No longer would the B-29s bomb from a high altitude. Instead, they would fly at less than 10,000 feet, under the cover of darkness. The lower altitude reduced the amount of fuel required for missions, while also easing the stress on the plane’s finicky R-3350 engines. And, in an extreme effort to reduce all possible weight, all the B-29s’ .50 caliber machine guns were removed, except for the twin .50s in the tail of the plane. Less weight translated into bigger bomb loads.

To minimize the exposure of aircrews to flak and fighters, LeMay introduced a concept he called “compressibility,” the bombers “forming up and concentrating over the target in minimum time to overwhelm the defenders.”‘ LeMay, who had flown a number of missions in Europe, wanted to lead this attack using the new tactics with his men, but he had been grounded for the sake of security after being briefed about the atomic bomb.

The B-29s’ primary weapon would be the

Tokyo, the first target for LeMay’s ten-day mini-blitz, would be the recipient of half a million such bomblets. In the lead-up to the raid on Japan’s most populous city on March 9 and 10, 13,000 men on three Pacific islands worked nearly non-stop for thirty-six hours to ready the fleet of planes for its mission. At 5:36 p.m. on March 9, 1945, the first B-29 crews started rolling down Guam’s runways and continued, one at a time, in fifty-second intervals. At the same time, planes began taking off from Saipan and Tinian.

After six hours of flight, at about 11:40 p.m., the lead elements of 325 B-29 Superfortresses from the 73rd, 313th, and 314th Bombardment Wings approached the coast of Japan. The crewmen donned flak vests and helmets and strapped themselves into their seats as tightly as possible. Only the dim light of a crescent moon and the stars above brightened the dense blackness.

Spread out over more than two hundred miles, the planes looked like giant roller-coaster hills horizontally staggered left and right of a center line, and vertically in steps at altitudes from 5,000 to 7,900 feet. Ironically, crewmen from the 73rd Bombardment Wing listening to Radio Tokyo on their flight to the city heard, among other selections, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” “My Old Flame,” and “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire.”

Just south of the Chiba peninsula, the great armada split in two. From there, the 314th flew parallel to the coastline of Tokyo Bay. The 73rd and 313th soared past the eastern side of the peninsula and then turned northwest.

At 12:07 a.m. on March 10, the lead pathfinders, sweeping in low and fast at nearly 300 miles an hour and at right angles to each other, unleashed their white phosphorous M47 bombs to mark the primary target. With superlative navigation, the crews managed to ignite a fiery cross on the ground to literally show that X marked the spot. The part of downtown Tokyo chosen for the attack measured about three by four miles, and was located between the southwest corner of the city’s main rail station and

Despite the evacuation from cities of great numbers of Japanese, including children, a huge population of essential laborers remained. The target area teemed with life: an estimated 750,000 workers crammed into the twelve square miles of low-income housing and family-operated factories. It may have been the most densely populated place on Earth. As more pathfinders flew over the target and released their payload, searchlights pierced the night sky, and succeeding planes quickly encountered both those beams of light and the anti-aircraft fire.

One of the lead aircraft was hit almost immediately and plunged like a ball of fire into the ground at 12:16 a.m. With the target area now clearly marked, planes from the main group started dropping their E-46 clusters onto a swiftly growing fire. From the ground, Father Gustav Bruno Maria Bitter said that the M69 bomblets reminded him of “a silver curtain falling, like the lametta, the silver tinsel that we hung from Christmas trees in Germany. And where these streamer touched the earth, red fires would spring up.”

Houses and buildings flared like the fuses of a firework as they were hit. Smoke rising from the city quickly infiltrated open bomb bays, and crewmen picked up an uncharacteristic odor — the sickening, sweet smell of burning flesh.

The thick smoke also created the potential for midair collisions. In one instance, two B-29s had begun their bomb runs at almost the same time, but at two different altitudes. As they converged on the city, the distance between them had become dangerously close. As the lower of the two planes was making final preparations, the co-pilot looked up and saw catastrophe in the making — a B-29 emerging from the smoke directly above them, its bomb bay doors already open. The co-pilot screamed the warning to the pilot, who immediately pushed the throttle forward and accelerated out from under the second B-29.

About an hour into the assault, the number of planes over the city had grown significantly, and the drone of their radial engines had become ever-present. The scene greeting these airborne crews was beyond anything they could have imagined. A wall of flames stretched across the horizon; it looked like Hell on Earth, a city engulfed in fire rising hundreds of feet into the air.

Powerful thermals belched from the ground, some as high as 20,000 feet. One collided with a plane, suddenly pushing it upward a thousand feet. Just as abruptly,

Another black column of billowing smoke rose from the surface and hit the right wing of one of the B-29s, completely flipping the plane into a 360-degree aileron roll, plunging it toward the burning city. Miraculously, the pilots managed to regain control seconds before the plane would have hit the ground.

Searchlights endlessly swept the sky looking for the massive bombers. Japanese crews manning the searchlights attempted to get multiple lights onto a single plane. When successful, the effect created what looked like an inverted cone above the plane. B-29s unlucky enough to get caught in the illumination cones were quickly subjected to concentrated Japanese machine-gun fire. The red, green, and yellow tracers streaked across the sky in long arcs, most falling below the planes.

Anti-aircraft batteries joined the torrent of fire, spewing flak shells that sent deadly shards of steel into the paths of the incoming B-29s. Shrapnel from the exploding flak shells sounded like pebbles rolling off the plane’s aluminum skin. The lethal barrage also included sporadic phosphorus shells that created blinding white flashes which momentarily incapacitated pilots in the night’s darkness. By far, the most numerous were the more common flak shells often seen in the European air war that looked like puffs of black smoke as they burst.

However, the Japanese added a fascinating variant to their flak shells. In an apparent effort to more rapidly establish the altitude of aircraft, the shells were chemically treated to burn green, red, and purple. The effectiveness of this practice, when paired with the illumination cones, proved fatal for at least one unfortunate B-29 and its crew.

Already trapped between two searchlights, a purple flak shell exploded just in front of the nose of one of the B-29s. Anti-aircraft crews quickly spotted the proximity to the bomber and followed it with several more rounds of purple flak. The next tore into the cockpit, instantly killing the pilots. More of the purple shells ripped into the crippled bomber. Seconds later, the plane rolled over and began a slow death spiral to the earth, crashing and exploding in a huge fireball.

While not in large numbers, Japanese aircraft attempted to defend the city against

Still flaming, parts of the two planes cartwheeled in the air and slammed into the ground. The tail section of the B-29 blazed across the sky before smashing into a field. One of the engines crashed into a hillside and disintegrated; the other three bounced and rolled, tearing up large swaths of earth. One massive piece of the wing, with flaming gas tanks inside, slowly circled like a spent and twisted red and orange boomerang, finally plummeting into undergrowth. The bodies of some of the crew, still strapped in their seats, lay scattered amongst the twisted wreckage.

An entirely different story unfolded at street level. The city had become a mass of flames, smoke, and explosions that rocked its inhabitants. The crescendo of air raid sirens blared in groans and wavering, high-pitched whines, mixing with blood-curdling screams.

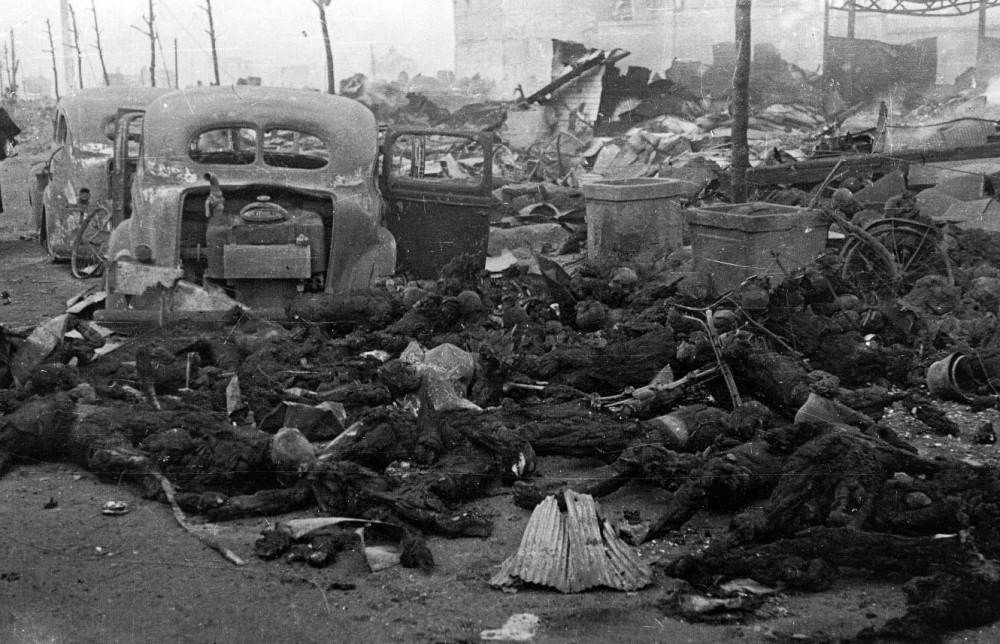

A few of the better-off inhabitants fled to the concrete shelters that they had buried in the ground around their homes. The fire’s roar sounded like a great freight train. Walls collapsed and large piles of rubble that once were buildings and homes burned out of control. Charred, blackened bodies lay everywhere. Thousands of firemen battled in vain to extinguish the inferno, in some cases using static water tanks. Rubble in the streets made it even more difficult for the fire crews to move equipment between the city’s crowded buildings.

Whipped by stiffening winds, fires spread quickly. Enormous balls of flame jumped from building to building with hurricane force, creating a tidal wave of flame. As the historian Barrett Tillman noted, “In those frightful hours, humans watched things happen on a scale that probably had never been seen." As superheated ambient air boiled the water out of ponds and canals, rains of liquid glass flew, propelled by cyclonic winds. Temperatures reached 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, melting the frames of emergency vehicles and causing some people to spontaneously combust. Exploding gas tanks blew buildings apart.

People were momentarily paralyzed by the awesome sight of the planes blanketing them like huge dragons — greenish from the searchlight beams, crimson from the glare below. Most people had no protection and ran around frantically to escape the heat, smoke, and flames; many were on fire. Some writhed on the ground in torment; others ran naked through the street, their clothing burned off. Some jumped into small containers of water intended for firefighting, only to be scalded to death. Thousands more crouched terrified in their wooden shelters, where they roasted alive. Large numbers of people attempted to flee to the great Buddhist temple in Asakusa; it

One mass of people crowded together in the street, staring at the flames. Firemen shouted to them to run for the bridge across the Kanda River, but a wall of fire blocked their path. Suddenly, a young man leapt up and led the way, jumping over tree trunks that burned like logs in a mammoth fireplace. Soon, others followed in a single file. Momentarily blinded by the intense light, he gasped for breath and stumbled, near the end of his endurance. Through the roiling smoke, he finally spotted the concrete bridge, which was crowded with squatting people. He ran to them and to his salvation.

The center of Tokyo glowed incandescent like the sun. Billowing clouds of smoke surged up, illuminated from below by orange flames. Scorched trees and telephone poles lay strewn across streets like giant matchsticks, their warped lines snaked out along the ground.

Not even the Gobunko, a bunker complex built into the hillside near the Fukiage gardens within the Imperial Palace compound, primarily for the protection of the royal family, escaped harm completely. Shortly after midnight, as the raid was just beginning, the emperor was still on duty in his underground command post, half-asleep and awaiting two important phone calls — one about the Japanese army’s final takeover of the puppet government in Saigon, Vietnam, the other about the birth of his first grandchild.

Unable to sleep due to the horrifying sounds of the raid, Hirohito remained safely sequestered inside his royal bunker. Eventually, the firestorm’s high winds reached the palace, dropping burning embers on the shrubs and camouflage surrounding the bunker, with starting several fires. Palace guards and other staff had only pails of water and branches to put out the flames, and, as they struggled to do so, its acrid smell infiltrated the space where Hirohito's family took refuge.

Sometime after 3:00 a.m., the hum of B-29 engines and the sound of air-raid sirens ended. Scattered clouds continued to glow, reflecting the flames of the burning city. Searchlights dimmed. As dawn broke, the light of day spread over the city and revealed a blackened and ashen landscape. Smoke curled into the sky as fires punctuated the now-practically-barren panorama.

Some of the worst killing grounds were the schools, according to Hidezo Tsuchikura, who, along with his two children, took refuge on the roof of the Futaba School. For ninety minutes, they took turns dousing each other’s clothing from a tank of water as their garments caught fire. Finally, after consuming the surrounding neighborhood, the fire receded. But, by then, only Tsuchikura, his children, and twelve other people remained alive.

He remembered that "the entire building had become a huge oven three stories high. Every human being inside the school was literally baked or boiled alive in the heat. Dead bodies were everywhere in grizzly heaps. None of them appeared to be badly

People ran to the Sumida River and leapt through walls of flame to dive into the water and onto the riverbanks. Layer upon layer of people all attempting to escape to safety crushed the early arrivals, and when the torrent of flames came, anyone holding their head above water risked being choked by smoke or seared by flame. The all-consuming fire sucked up the oxygen, suffocating thousands.

The captain of one fire company was stunned by the scene he found on the Ryogoku Bridge, “a forest of corpses’ packed so closely that they must have been touching as they died. They had returned to humanity’s carbon existence, crumbling at the touch.”

The entire river surface was black as far as the eye could see, black with burned corpses, logs, and who knew what else, but uniformly black from the immense heat that had seared its way through the area as the fire dragon passed. It was impossible to tell the bodies from the logs at a distance. The bodies were all nude, the clothes had been burned away, and there was a dreadful sameness about them - no telling men from women or even children. All that remained were pieces of charred meat. Bodies and parts of bodies were carbonized and absolutely black.

As the waves along the riverbanks receded, more bodies revealed themselves: stacked in neat precision, as though by some machine ... row upon row of corpses. The tide, which had come and gone since the firestorm passed by, left rows of bodies like so much cordwood cast up on the beach. How many bodies had washed out to sea was impossible to tell, but they must have been in the thousands, for there were tens of thousands in the river.

Incendiary bombs had rained down on Tokyo for nearly three hours. The raid caused an urban conflagration, a firestorm much like the one that had destroyed Dresden, Germany, just a few weeks earlier,

While American bomber crews sustained losses, a little less than five percent of the force, casualties were slightly lower than expected, and were deemed acceptable. LeMay’s new tactics were an unmitigated success, in terms of the damage inflicted on the capital. They also exposed the vulnerability of Japanese air defenses and the inadequacy of their firefighting facilities, which were totally overwhelmed.

Three and half years earlier, General George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, told news reporters in an off-the-record briefing on November 15, 1941, three weeks before Pearl Harbor, that “if war with the Japanese does come, we’ll fight mercilessly. Flying Fortresses’ (B-17s) will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There won’t be any hesitation about bombing civilian. It will be all-out.”

Marshall's prediction had now been seared into the fabric of the war against Japan (and with Germany well before March 10). And, by 1945, the military had the concurrence of the American public. Time magazine, for example, described LeMay’s firebombing of Tokyo as “a dream come true” which proved that “properly kindled, Japanese cities will burn like autumn leaves.”

In the aftermath of the attack that morning, Tokyo Radio broadcast the following message: “During an air attack on the city of Tokyo last night, our imperial forces destroyed over one hundred American planes. It was a great victory for our forces, who will continue to fight for the honor of our emperor and until our enemies are driven away.”

The actual number was just fourteen. The bombing also precipitated an exodus from the capital, with more than a million people leaving on their own accord in the weeks following the raid. And, regardless of the positive spin Japanese propaganda attempted to put on the event, no one living in or visiting Tokyo could fail to understand the attack for what it was—a catastrophe greater than the city had ever seen. They also knew that, if the Americans were able to project such a powerful force, it. meant they would be back, likely soon.

Nine days after the firebombing of Tokyo, Emperor Hirohito decided to see for himself the destruction wrought by the air raid. That morning, his small entourage of just two cars drove slowly through the remains of Tokyo. The first car was flanked, front and rear, by two motorcycles, each with sidecars. The second car, occupied by the monarch, was a large, two-toned, crimson

As the vehicles moved through the ruins, the view in every direction was of a vast, flattened wasteland dotted by stone statues, concrete pillars and walls, the skeletal steel frames of buildings, and a scattering of telephone poles. Nearby, small groups of civilians in ragged clothing dug through the rubble for anything of value, most with empty expressions on their faces. They watched the visitors with reproachful eyes as the tiny motorcade passed.

Occasionally, the cars pulled off to the side of the road, and Hirohito, carrying a cane, got out with his doctor, chamberlain, and several men in military uniforms to speak with local officials. In one ward alone, only fifty of 13,000 homes remained intact, and more than 10,000 residents were either dead or injured. Ultimately, it would take four weeks to dispose of all 84,000 corpses.

By the time Hirohito visited the devastation brought to his capital by LeMay’s new tactics, the American general had already conducted a mini-blitz against Japan, hitting the cities of Nagoya (twice), Osaka, and Kobe. In a period of only ten days, the Americans flew 1,595 sorties and dropped 9,373 tons of bombs, destroying thirty-one square miles at a cost of just twenty-two airplanes.

The pace, scale, and ferocity of the attacks shocked the Japanese. And LeMay was just getting started. By war’s end, he would obliterate 40 percent of Japan’s sixty-six largest cities, destroy 2.3 million homes, and render homeless approximately 30 percent of the entire urban population of the nation. After another attack on Tokyo in late May, the emperor and his family would be forced to move from their residence to the Gobunko.

Still, during the final months of the war, Japan’s leaders would never leave their capital, which would be bombed several more times before the end of the conflict. It would have been seemingly incomprehensible to ignore the magnitude and relentlessness of LeMay’s aerial assaults, and to harbor any doubt about how powerful their enemy had grown, or what its intentions, were as long as Hirohito and his supreme war council refused to surrender.