Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

As the Allied armies closed in on the German capital in 1945, the complications for ending the war in Europe paled, in comparison with the difficulty of forcing a Japanese surrender. For the Japanese military, the concept was unthinkable, a state of mind confirmed by the hundreds of thousands of Japanese servicemen who had already been killed, rather than giving up a hopeless contest.

For the Japanese leadership, the whole strategy of the Pacific war had been predicated on the idea that, after initial victories, a compromise would be reached with the Western enemies to avoid having to fight to a surrender. Switzerland was thought of as a possible neutral intermediary; so, too, the Vatican, for which reason a Japanese diplomatic mission was established there early in the war.

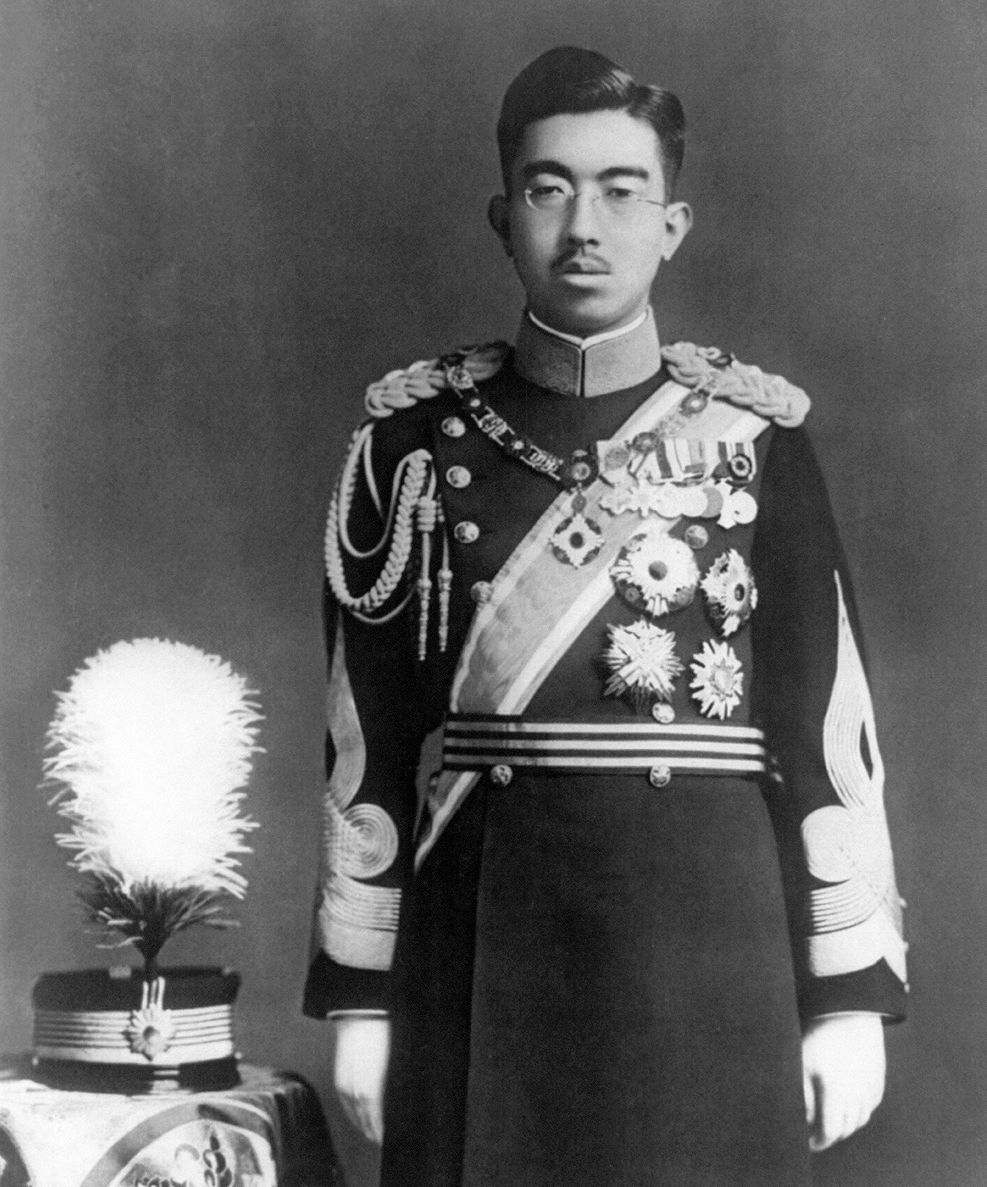

The Japanese government watched the situation in Italy closely, when General Pietro Badoglio became prime minister after the fall of Mussolini's fascist regime, and remained in power after the Italian surrender in 1943. If Badoglio could modify unconditional surrender by retaining the government and Victor Emmanuel as king, then a “Badoglio” solution in Japan might ensure the survival of its imperial system.

When a new cabinet was formed in April 1945, after months of military crises, the new prime minister, 78-year-old Kantaro Suzuki, announced on the radio that “the current war has entered a serious stage in which no optimism whatsoever is permissible.” After hearing the broadcast, the former premier, Hideki Tojo, told a journalist, “This is the end. This is our Badoglio government.”

Suzuki was appointed after discussion with the emperor and the Council of Elders because he was among the influential in Japan who favored finding a way to end the war on acceptable terms, but, like Badoglio, he also endorsed the continuation of the war to satisfy the military hardliners in the government who would brook no prospect of surrender. Throughout the months leading to the final capitulation, Japanese politics remained torn between the desire for peace and the imperative to fight if peace proved too costly.

Formal and informal approaches were made to both the United States and the Soviet Union to test whether a negotiated peace might be possible, even though the serial rejection of all Japanese efforts since 1938 to reach a compromise peace agreement with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government ought to have dampened expectations. In April 1945, feelers were put out to see if the same Swiss avenue could be used for Japan. The Japanese naval attaché in Berlin sent his assistant, Fujimura Yoshikazu, to Switzerland, where he succeeded in meeting America's OSS