Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

Editor’s Note: Benjamin Banneker was born free in 1731 in Baltimore County, Maryland in an environment in which abject deference to white people was not as deeply embedded as it was farther south. He was gifted in the sciences and became a naturalist and almanac-maker. In his 60th year, he wrote a letter to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, challenging the famous espouser of liberty – and owner of over 200 slaves – to get beyond the doctrine of white supremacy and to support racial equality in the new nation.

Edward J. Larson is the author of seven books and won the Pulitzer Prize in History for Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. His latest book is an important look at the twin strands of liberty and slavery in our nation’s founding, American Inheritance: Liberty and Slavery in the Birth of a Nation, 1765-1795, from which this essay was adapted.

“I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion,” Benjamin Banneker wrote to Thomas Jefferson in August 1791, “when I reflect on that distinguished, and dignified station in which you stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.”

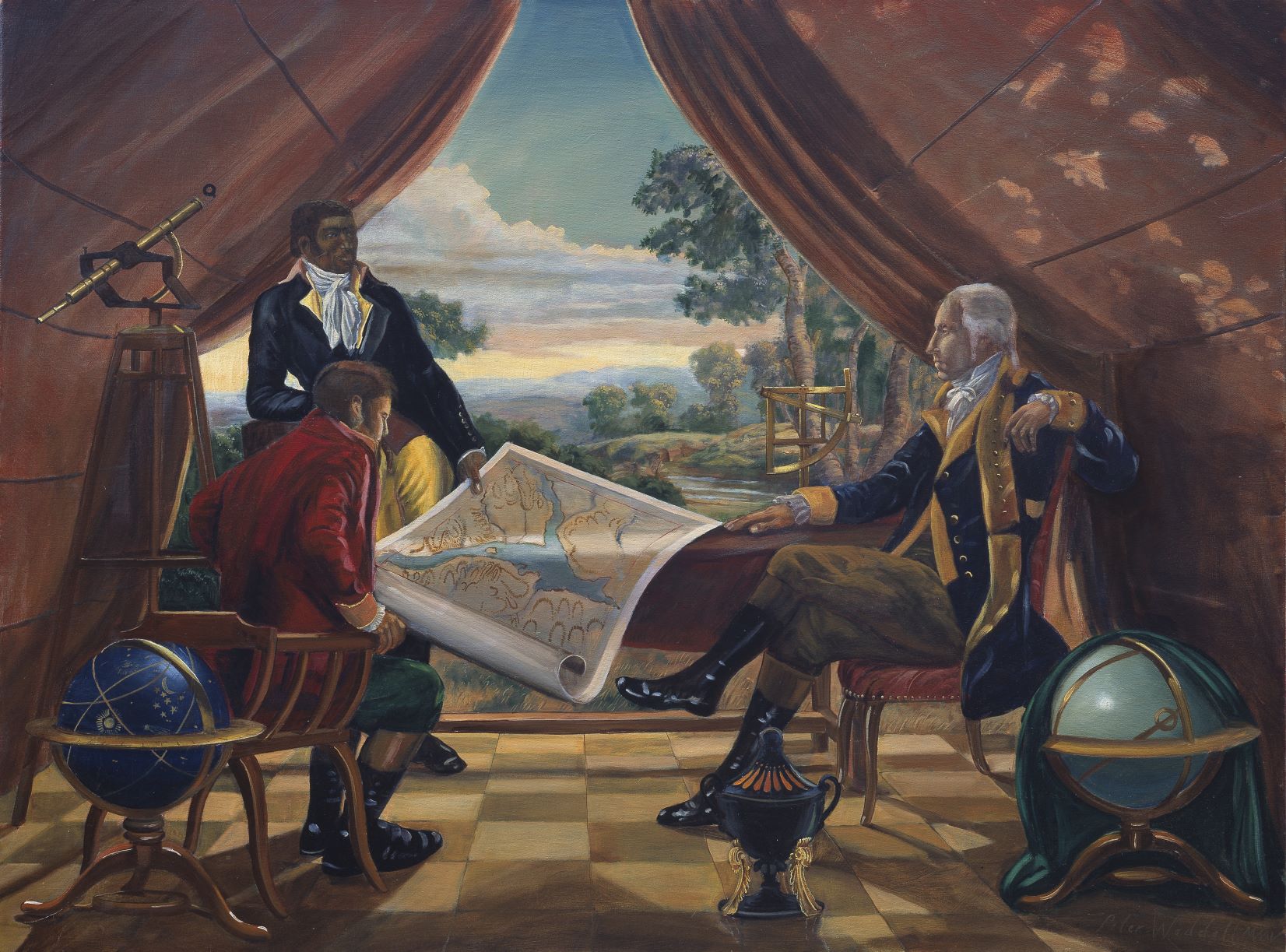

Jefferson was serving as America’s first secretary of state, with duties that included overseeing a boundary survey for the new federal district in Maryland and Virginia. Earlier in 1791, Banneker, a free black farmer and almanac-maker from rural Maryland, briefly assisted the Quaker land surveyor Andrew Ellicott with the federal district survey. Banneker lived near the Ellicott family gristmills, and Andrew Ellicott’s cousin had encouraged Banneker’s talent for computing the local times for future sunrises, sunsets, and other celestial phenomena.

When Banneker sent a table of his calculations for 1792 to Andrew Ellicott, who also made such ephemerides, Ellicott forwarded it to Pennsylvania Abolition Society president James Pemberton. He then shared it with Philadelphia astronomers and mathematicians as evidence of the reasoning ability of black people at a time when comparative anthropology was in its infancy.

The relative intellectual abilities of blacks and whites had emerged as an issue in the Revolutionary-era debates over slavery. In his 1776 Dialogue Concerning Slavery, the abolitionist-minded New England theologian Samuel Hopkins complained that white Americans viewed blacks as fit for slavery because “we,” as whites, “have been used to look on them not as our brethren, or in any degree on a level with us; but as quite another species of animals.” Slavery would end, he wrote,