Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

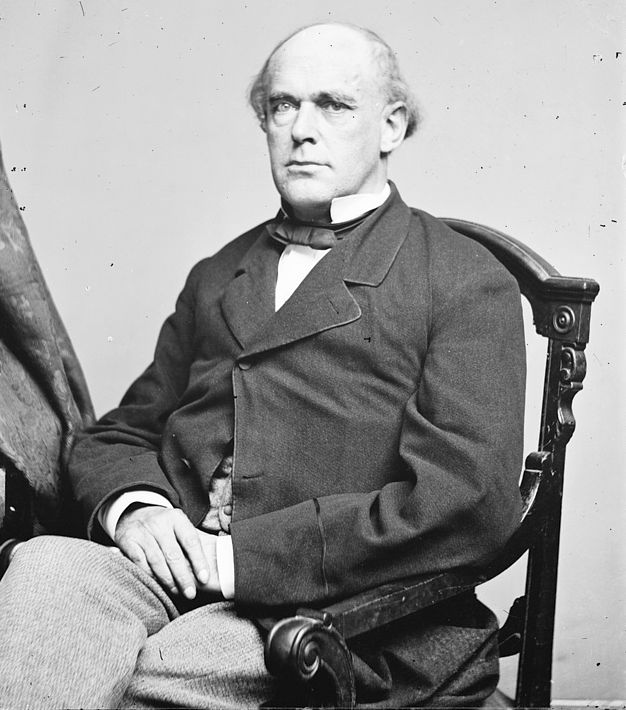

Editor's Note: Walter Stahr is a historian whose essay “The Struggles of Edwin Stanton” appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of American Heritage. His most recent book is the widely praised Salmon P. Chase: Lincoln’s Vital Rival, in which portions of this essay appeared.

Zion Church, the largest black meeting house in Charleston, South Carolina, was packed for a political meeting on the afternoon of May 12, 1865. Most of the five thousand people there had started their lives enslaved and gained their freedom only a few weeks earlier, when the Union army finally arrived in town.

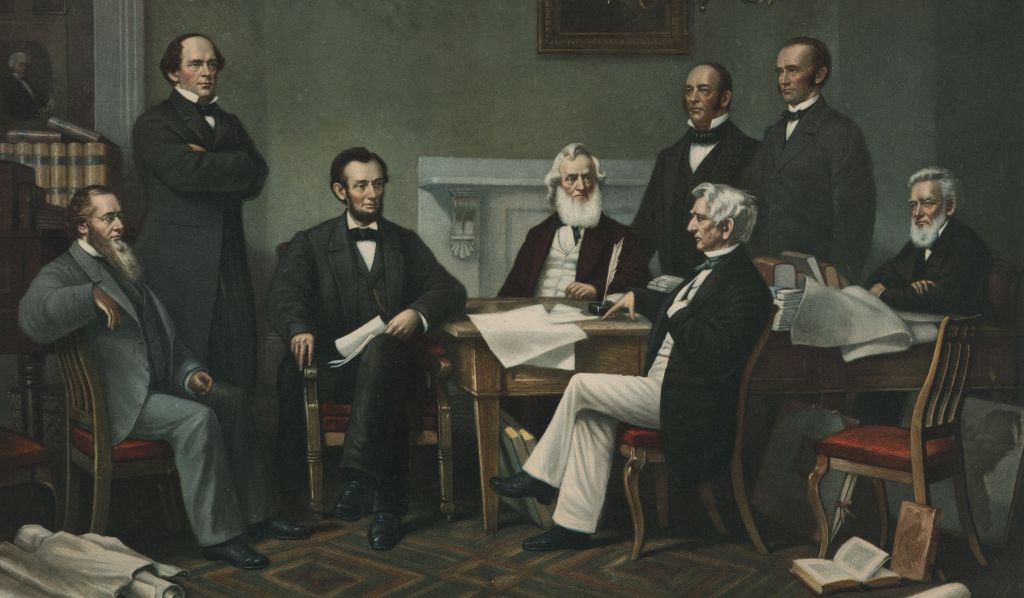

The main topic of this meeting, as the last rebel die-hards fought the last battles of the Civil War, was reconstruction — the process of forming new state governments in the South, and whether blacks, as well as whites, would participate in the process. The afternoon’s first speaker, a white Union general, said that blacks had earned the right to vote through their service during the war. The remarks of the second speaker, a black army major, were interrupted by the arrival of the Chief Justice of the United Stares.

The black crowd stood and cheered, and the military band played “Hail to the Chief,” as Salmon Portland Chase walked down the aisle and up to the platform. “More than anyone else, he looked the great man,” one of his friends recalled: six feet tall, solid, strong, clean-shaven, nearing sixty.

The crowd cheered him not because of his work on the Supreme Court (he had been chief justice for only a few months) or because of his work as Treasury Secretary during the Civil War (although some called him “Old Greenbacks” for his role in creating the new green paper currency and putting his own face on it). No: the black Charleston crowd cheered because Chase was known as a lawyer who had defended fugitive slaves, and a leader who, in his various government roles, who always argued against slavery and in favor of basic rights for blacks.

Chase did not disappoint his audience. He said that their future was at last largely in their own hands. “Let the soldier fight well, let the preacher preach well, let the carpenter shove his plane with all his might, and the planter put in and gather in as much corn or cotton as he can.... Act thus, and I have no fears for your future.” He told them that he had been speaking for black voting rights for twenty years, since he had given a similar speech in Cincinnati, but he cautioned that mere