Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

Authors: Derek Leebaert

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

Editor’s Note: Derek Leebaert is the author of several books on American history and the military, including Unlikely Heroes: Franklin Roosevelt, His Four Lieutenants, and the World They Made. He is a founder of the National Museum of the United States Army.

A short article in the Sunday New York Times of March 9, 1930 reported a lecture to the American Society of Agronomy by one Henry Wallace, 42. Apparently, his experiments in the scientific breeding of corn promised a huge increase of productivity for Midwestern crops. The Times was glimpsing what would become the Green Revolution after World War II, which multiplied the world’s food supply to save over a billion lives by 1975, a decade after Wallace’s death.

For three generations, Wallace’s staunchly Republican family had run the important weekly, Wallaces Farmer, out of Ames, Iowa. The Great Depression drove their paper into the hands of creditors, while Henry struggled to keep alive a biotech company. Yet he campaigned for Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, although politicians found Wallace remote. That said, any man who combined brilliance, lonely idealism, involvement with the land, and an element of desperation was likely to appeal to another very unusual man, Franklin Roosevelt.

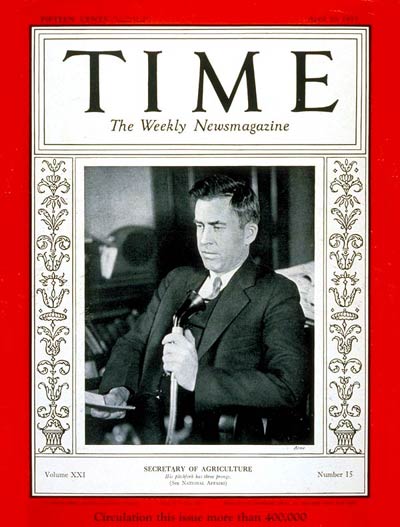

FDR appointed Wallace to head the Department of Agriculture, the biggest federal agency, and The Times then profiled him in depth. It described Wallace’s total recall for numbers, his brain a “machine powered by curiosity,” and acclaimed him as an astute administrator. Altogether, The Times observed, his intellect was “freakish.”

Wallace was nearly six feet tall, weighed 175 pounds, had a lean face, chiseled features, blue eyes, thick reddish-brown hair, a starchy voice, and the mild untidiness of a man who was happiest in his fields. He became one of only four hands-on operators to remain at the top from spring 1933 until FDR died in April 1945. The others were Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, and Harry Hopkins, the de facto secretary of public welfare until he became FDR’s political-military alter ego during World War II.

The four became friends. Together, they composed the tough, enduring, liberal core of this presidency — and were indispensable to FDR’s achievements in peace and war.

Beginning in 1933, it was Wallace who launched the programs that transformed the political economy of American agriculture. Much went wrong with a brutal conservative approach that enforced scarcity by paying farmers not to farm. Big landowners benefitted,

In conversation, Henry Wallace dealt nearly as an equal with Albert Einstein when they received honorary degrees at Harvard in 1935. He also enjoyed illuminating dialogues with John Maynard Keynes, the British mathematician who founded modern macroeconomics. Among politicians, one of the few men able to engage with Wallace’s intellect was Roosevelt.

FDR was not the insouciant Edwardian gentleman he pretended to be. His French was fluent, of course, and he also read Spanish easily and enjoyed chats in Dutch. Wallace concluded from their intense conversations that FDR’s knowledge of climate and geography was unsurpassed. The president, he observed, also excelled at handling logistics — in time, a critical attribute for a war lord. And each man was absorbed by the planet’s vast unopened spaces like Brazil, central Asia, and Siberia.

During FDR’s second term, Wallace began to eye the presidency, and addressed himself to America’s altering world role. His German was as proficient as FDR’s, and each recognized Hitler as a madman. Still, Wallace felt compelled to advise Roosevelt that attempting diplomacy with Hitler would be like “delivering a sermon to a mad dog.” Nor should the president keep fomenting political quarrels over class. National unity, cautioned Wallace, would be vital for rearmament, not least against Japan.

FDR had dispatched his shrewd, tough vice president, John Garner, to face Emperor Hirohito in Tokyo. That visit had deterred nothing, and, by the late 1930s, the Imperial Japanese Army had pushed deeply into China.

In Europe, war erupted on September 1, 1939, which opened the unprecedented opportunity of a third term for Roosevelt. He said nothing about his intentions. By December, Garner, of Uvalde, Texas, declared his candidacy. He was the greatest legislative strategist of his generation, and he led the Texas delegation in Congress, which was the most powerful that any state has ever sent to Washington. That said, Roosevelt never wanted a VP like Garner again.

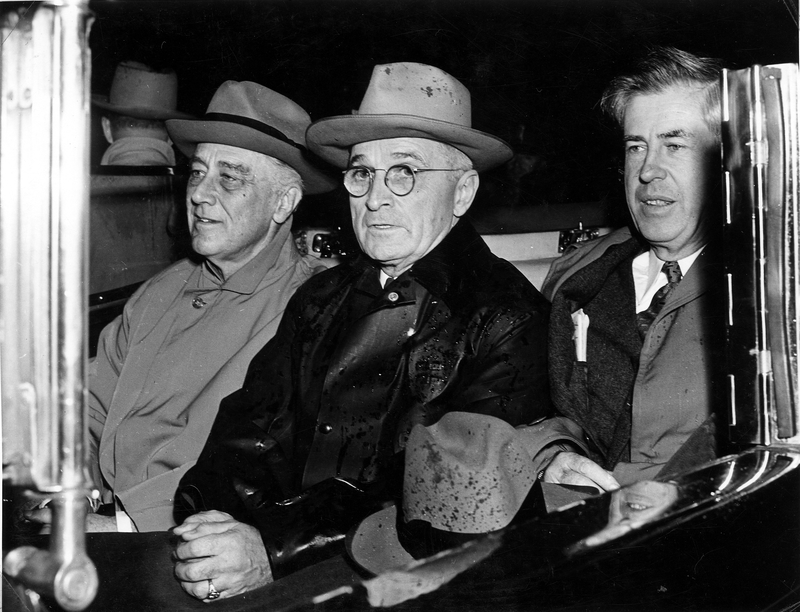

By July 1940, Roosevelt told the Democratic Party convention that, this time, Henry Wallace had to be his running mate. The delegates objected: Wallace was unsociable, and not a joiner with the boys on Capitol Hill. FDR was unyielding because, Frances Perkins recalled being told, he liked “the way Henry thinks.” Another reason was that

Wallace applied his astonishing intellect to become the most powerful of America’s vice presidents, at least into 1943. He was pivotal during America’s run-up to war, though historians tend to overlook this. Roosevelt sure hadn’t “aroused the country,” Harold Ickes concluded. Nor could that daunting Interior Secretary try doing so himself: everyone knew that Ickes had long wanted to attack Japan, Germany, and any dog that barked. As for the secretaries of war and of state, each was too low-key.

Throughout 1941, Wallace’s speeches, interviews, and writings made military intervention respectable at a time when people still saw the prospect of war as playing into the hands of Jews, Wall Street, the British empire, and other “globalists” of the day. He spoke with the passion of a man of the soil from the isolationist heartland who imparted moral authority to the sacrifices that the crusade to come would exact. All this carried weight across the Midwest, and any deep shift in Midwestern opinion would, to some degree, pull the whole nation with it.

FDR gave Wallace additional hands-on operational duties once America entered combat, which was unprecedented for a vice president. Yet Wallace contributed much more to the cause than managing economic warfare.

In May 1942, he delivered one of this country’s great speeches. He told the world of the republic’s war aims, proclaiming “the Century of the Common Man.” America now stood against the devil and all his demons to exert Christian “social justice.” The New Deal had to be spread through the world because all people are made in the image of God: spread to the Middle East, to India, and Africa. So motivated, he argued, the American people would fight with relentless fury: “The Götterdämmerung has come for Oden and his crew.”

It was the “most moving and effective thing produced by us during the war,” said the cerebral columnist, Walter Lippmann. The speech was translated into twenty languages, distributed worldwide, and turned into Paramount’s Oscar-nominated The Price of Victory. The purpose of the United States was clear.

Right after the cabinet meeting of February 19, 1943, Wallace wrote that evening in his diary that Roosevelt had told him “about the necessity of someone of Cabinet rank visiting Russia.” The president had urged Wallace to do so, and to “demonstrate to Stalin why he could not expect too much from us.” The Soviet Union had become an ally after Hitler’s June 1941 invasion, yet FDR had never met the tyrant. At this juncture, Roosevelt needed to send the highest-possible emissary to explain why America and Britain

Despite the president’s request, Wallace appraised the world differently. It seemed more important to first shore up U.S. ties in Latin America, which was exposed to Nazi subversion. FDR was persuaded, and he spoke instead of Wallace seeing Stalin over the summer. Speaking excellent Spanish and Portuguese, Wallace therefore flew south in mid-March, rather than to Moscow, as the president initially had hoped.

On the home front, FDR kept proving himself a dreadful administrator. Wallace snorted about Roosevelt and Hopkins “trying to cook up one of their typical overall reorganizations,” except, in the summer of 1943, Wallace got ensnared in their latest juggling of personnel. He lost much of his hands-on authority over economic warfare, but barely noticed. Now, he had more time for speeches, and he was turning into an impressive politician. Moreover, he was championing the New Deal, while the president had to focus on the war. Getting into FDR’s sunlight to that extent was supremely risky.

Finally, in May 1944, Henry Wallace flew to the Soviet Union on a goodwill mission. But this time, FDR did not want him to visit the Kremlin. There was no need. FDR and Stalin had finally met the previous December in Tehran.

Instead, Wallace journeyed to Russia’s far-eastern regions. Roosevelt and Wallace each believed that Siberia and central Asia had vast potential for postwar U.S. trade, perhaps enough to offset a return of the Great Depression once the stimulus of military spending had ended. And, while in the Far East, FDR suggested, Wallace should also visit China, another sprawling U.S. ally.

Wallace returned to Washington a week before the Democrats convened in July to nominate Roosevelt for a fourth term. Polls showed decisive grassroots support for Wallace to remain Vice President. Yet Roosevelt quietly got the party’s big-city bosses to throw Wallace off the ticket. Historians keep debating why. One reason stands out. By this point, Wallace had turned into a high-powered politico with his own national constituency. He had become the voice of both the New Deal and of America’s postwar vision. For FDR, that degree of prominence in a VP was anathema. He instead found a comfortable alternative: decent, middlebrow, machine-backed Harry Truman, who was popular in the Senate.

Therefore, 82 days after Roosevelt’s fourth inauguration, it was Truman who became president. Wallace had told FDR that he was happy to instead serve as secretary of commerce, and Wallace kept that role under Truman. At least until September 1946, when Truman fired him over a foreign-policy dispute involving Secretary of State James Byrnes concerning how closely America should cooperate with the British empire. Wallace finally ran for president in 1948 as a Progressive. He

Wallace left politics and returned to the research which was set to transform the world. When history is written a century from now, one of the outstanding 20th century figures will be the plant geneticist Henry Wallace, with Wallace the politician being a blip. Even today, fellow tech moguls recall this supposedly quixotic leftist as a mega-entrepreneur who turned that struggling startup of 1932 into a colossus, which, in time, his family sold to Dupont for $9.4 billion.

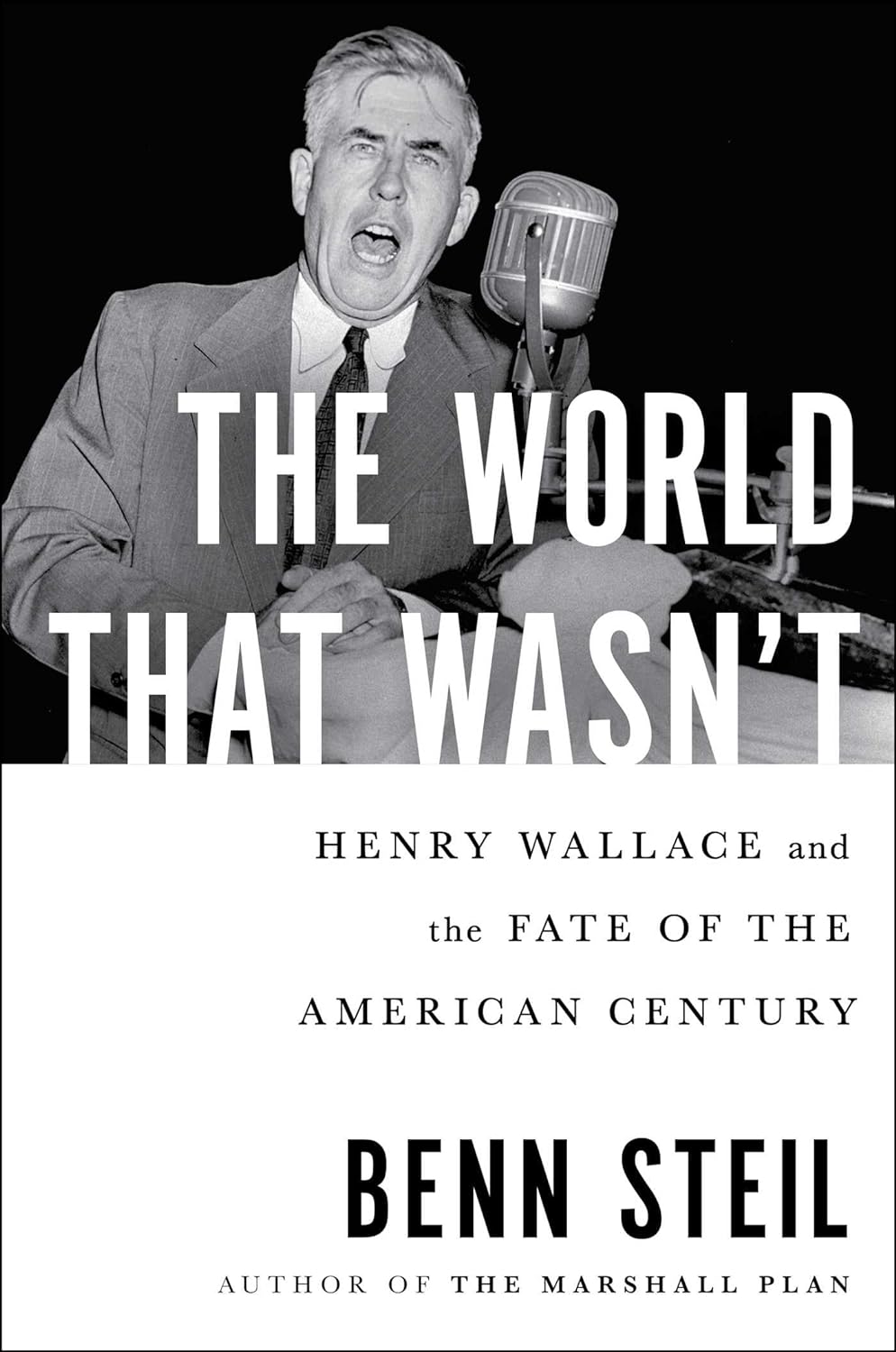

Nearly 60 years after his death, Wallace merits a large, fresh biography. It’s offered by Benn Steil, the prize-winning author who is the senior fellow and director of international economics, as well as historian in residence, at New York’s venerable think tank, the Council on Foreign Relations. The World That Wasn’t: Henry Wallace and the Fate of the American Century, is full of well-mined sources, novel interpretations, and documents from the Russian State Archives.

Steil argues that Wallace was neither heroic nor a well-meaning visionary, and he berates previous biographers for their “credulous treatment” of Wallace. In his telling, the world would have been disastrously different had Wallace become president in 1945, let alone been elected to a full term in ’48. The World that Wasn’t has arrived in early 2024 with impressive blurbs and reviews from top historians.

Steil admires Wallace’s intelligence and passion, and he notes his important contributions to science. Still, he regards Wallace as self-absorbed, hungry for office, and ready to use Soviet influence to further his ambitions.

What is this “world that wasn’t” which Steil believes was averted by a whisker? After history’s worst war ended in 1945, “there would have been no Truman Doctrine, no Marshall Plan. No NATO. No West Germany. No policy of containment.” Therefore, Stalin would have dominated Northern Iran, Greece, and the Turkish Straits, all of Germany, the Korean peninsula, and Hokkaido.

As a private citizen, Henry Wallace had indeed opposed these building blocks of what became known as the “American Century,” a term coined in 1941 by publisher Henry Luce, who had advocated American political-military preeminence following the war, to be backed at gunpoint. Wallace, as we’ll see, had his reasons.

From the start, Steil builds his case for Wallace’s self-serving encounters with Moscow, about which, at best, Steil claims, he was “lacking in candor.”

Except for the outlines of Wallace’s career and some notable events — like the

Only four of the book’s eighteen chapters concern Wallace during the New Deal era before 1940, and 62 pages of those chapters address an oddball episode that went on from 1933 through 1935. It involved bizarre characters whom the State Department speculated were “Russian agents.”

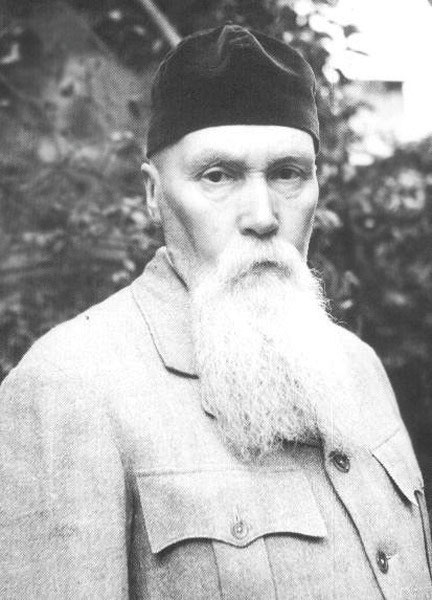

Nicholas Roerich, or the “Guru” to his disciples and a slice of New York society, was a Russian-born artist, amateur archeologist, and shave-headed cult leader who yearned to establish a theocratic state in central Asia, with Kremlin support for his “New Country.” Perhaps the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture could help.

Wallace was a man who had long felt isolated and had sought spiritual support. He consulted an astrologer and spiritualists in 1929, having turned to theosophy; he called upon an occultist and a Native American medicine man in 1930. In 1931, he dropped Presbyterianism to join the Episcopal Church. There he found solace. For fifteen years, he and his wife Ilo would worship on Sundays with Frances Perkins at St. James Church on Capitol Hill. Still, we read that Wallace at this juncture had a “cult-addled mindset.”

Wallace backed the Russian artist and intellectual Nicholas Roerich’s expedition to Mongolia with government money. Scientists from the Agriculture department accompanied the trek to collect drought-resistant plants for study. Yet Roerich had his own nation-building ambitions. Soon, Cordell Hull, FDR’s secretary of state, complained about private adventurers and people from the Department of Agriculture intruding into a delicate region over which Stalin loomed.

Before long, the expedition’s quasi-political activities were getting bad press, too. Wallace felt betrayed by Roerich, and he smashed him. Steil does not report that Wallace asked the nation’s preeminent banker, Winthrop Aldrich at Chase National, to cut off every public and private means of funding to the Russian and his team, thereby stranding the travelers in the middle of nowhere.

Wrapping up this episode, Steil shows Wallace dodging criticism by writing a letter for the record: the Roerich expedition’s purpose was to find plants, nothing more, and surely not to create a cockamamie central Asian polity. This letter underscores Wallace’s “dishonesty and moral cowardice,” says Steil.

He uses Soviet sources for this lengthy tale, provided by a researcher in Moscow. Yet there was another player among Roerich’s two “most important American recruits.” That was Roosevelt who, it’s said in passing, received

The World That Wasn’t then leaps to 1940, except for a bridge that shows Wallace’s department to have been penetrated by Soviet spies like Alger Hiss. Steil doesn’t report that, in 1936, Hiss segued to the State Department, nor that Soviet spies had penetrated almost every federal agency, plus the White House staff. He only spotlights Henry Wallace’s Agriculture Department.

The jump to 1940 is unfortunate because — when examining vistas that were and weren’t — there’s much to say about how Wallace, Frances Perkins, and Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles struggled in the late 1930s to convince FDR of the validity of Keynes’s theories of stimulative spending. As it was, the Depression gripped America until the mailed fist of military Keynesianism — huge government outlays for rearmament by 1940 — finally revived the economy.

Wallace asked the formidable John Garner to swear him in on January 20, 1941. By then, Steil insists, “no one thought more highly of Henry Wallace’s abilities than Henry Wallace.” As VP, he continues, Wallace took “a philosophical path” that led him to regard Stalinist Russia on the same moral plane as the United States.

However, the war years were a time when even Walter Lippmann spouted hopeful nonsense about the Soviet ally, like claiming that the future of world peace lay in the “movement of opinion within the mass of the Russian people who are now much waked up.” Pressed on by the vox populi to believe Lippmann, Roosevelt and Stalin might have developed a noble friendship.

Yet Steil portrays Wallace as an outlier on communism. For instance, he’s shown speaking in 1942 at a sold-out Congress of Soviet American Friendship rally in Madison Square Garden — and declaring that “democracy” thrived in both lands. All of which sounds ominous, except for the fact that Lt. General Leslie McNair, commanding general of the Army Ground Forces, joined Wallace on the podium to say much the same thing.

Steil becomes truly eccentric when assessing Wallace’s epic “Common Man” speech. To him, it is “meandering and, at points, strange.” By this point in the book, other problems of fact are accumulating.

It’s immaterial that Steil sees Wallace as having little “administrative talent,” while leaving “the grind work of actual policymaking” to deputies. Except, as The Times’ profile understood, that’s how effective leaders run big organizations. Yet we then read that Wallace “loathed” Harold Ickes, which is absurd. So too is the notion that Harry Hopkins was “Roosevelt’s most trusted friend.”

First, Ickes and Wallace were

A graver matter is how Steil presents Wallace’s response to Stalin’s 1939 invasion of Finland. He writes that Andrei Gromyko, just arrived as counselor at the Soviet embassy, cabled Moscow in 1942, asserting that Wallace had claimed “the Soviet Union was right” to have invaded three years earlier. If true, Wallace’s opinion would have been despicable. Yet it is extremely unlikely that Wallace held this opinion. His sister, Ruth, who was married to Sweden’s ambassador, lived with her family in Helsinki during the invasion, which Steil seems unaware of. Ambassador Wijkman, his wife, and Wallace himself were all outraged. And why believe Gromyko’s reports?

The difficulty of using Russian archives, when an author doesn’t read the language, is that contractors can make it difficult to see what’s significant, or reliable. The problem is apparent in Steil’s long story about Nicholas Roerich. Original Soviet-era sources are piled on to little purpose. Moreover, authors yearn to believe the substance of whatever a costly researcher might dig up from tantalizing, recently hidden state papers. Clearly, as in this example of Finland, Gromyko was relaying hearsay. He would rise to become the Soviet ambassador to the U.N., and The World That Wasn’t cites scores of his secret cables, memoranda, and impressions. Starting with his report to Stalin about Wallace and Finland, readers begin to doubt the value of this new-found cache.

“Since the heady early days of the Roerich expedition,” Steil continues, Wallace saw his calling in foreign affairs. As Vice President, he importuned an “incredulous” FDR to send him to Moscow in 1944 because, Steil adds, “Wallace craved an audience with Stalin.” Steil never mentions that, a year earlier, it was FDR who had urged Wallace to see Stalin, and that Wallace had declined.

To include that detail would torpedo Steil’s thesis that “for years, Wallace had pined for an audience with Stalin.” No, Wallace had not “pined for an audience,” let alone to further a reckless ambition for shaping the world with Soviet assistance. Otherwise, he would have gone to Moscow in March 1943, rather than to South America.

As it was, FDR and Wallace poured over a map in the spring of 1944 and gauged the weather for Wallace’s 51-day journey through Siberia, Mongolia, and into China. (Roosevelt loved planning other people’s trips.) Biographers have described this journey before. Moreover, it defies belief, contrary to what Steil claims, that FDR was

Steil contributes pages of Russian-language references about Wallace’s trip, yet they add little beyond anecdotes. Wallace delivered speeches in Russian, as Steil doesn’t add, and the wartime press acclaimed his journey. Just by showing up in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, to add a new detail, Wallace helped to keep Buddhism alive during the Stalinist oppression, as monks today will attest.

Nonetheless, Wallace found himself deceived by Stalin’s head of State Security Far East, NKVD Colonel-General Sergei Goglidze, who was masquerading as a civil administrator. The gulag’s chief executioner showed off Potemkin villages of robust settlers joyfully developing the frontier. Guards in work clothes had been substituted for the starving prisoners of Kolyma’s death camps. Wallace unwittingly lauded the settlers’ pioneering spirit and Stalin’s leadership. Years later, Wallace would blame himself for falling prey to this maskirovka (“disguise”) operation, an art at which the Soviets were superb.

Yet Steil is harsh. Wallace, who “presumably” knew that 13,000,000 of Stalin’s subjects had died from collectivization, was “willing to be fooled” by a landscape of “mines and factories manned by slaves.” In China, we’re to understand, Wallace dealt with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government “in a manner decidedly friendly to Soviet interests.”

Steil and his Moscow-based researcher again rely on Soviet archives, all of which they assume to be accurate. Meanwhile, endnotes can be incomplete. One example is the claim that Wallace believed those millions of dead were “necessary” for the Soviet Union to industrialize. No source exists for such calumny. Altogether, Steil explains that “an ongoing postwar partnership with Russia was, curiously, at the heart of Wallace’s foreign policy.” That such a “partnership” was likewise at the heart of Roosevelt’s foreign policy goes unnoticed.

FDR told his cabinet that he expected more trouble from the British empire after the war than from Moscow. Wallace agreed. He was no more naïve about the Soviet Union, nor more ignorant of its vast prison-labor complex, than was Roosevelt. As the Red Army smashed into Eastern Europe in 1944, however, it was the nonchalant president who convinced himself that he could handle Stalin as swimmingly as he did the Democratic party bosses.

Overall, The World That Wasn’t is dated in its understanding of how FDR’s presidency functioned. Steil is unaware of what Roosevelt scholar Susan Dunn calls the “collective leadership” that existed under FDR’s scrutiny. Much of Wallace’s accomplishments as Secretary of Agriculture, and then as Vice President, were in league with the goals of Ickes, Perkins, and/or Hopkins. Yet they barely appear.

Acute critical speculation can be helpful when writing history, and The World That Wasn’t provokes readers to picture President Wallace in the White House starting on April 12, 1945. But “what if’s?” point both ways, and the Oval Office tends to transform its occupants, as it did Harry Truman. Why believe that a

Wallace was capable of radical disillusion, as over Nicholas Roerich’s expedition. It’s equally likely that an angry President Wallace — privy to official intelligence — would have responded ferociously to Stalin’s predations in Eastern Europe. Steil is oblivious to this alternative possibility, despite seeing Wallace as a compelling figure “for counterfactual history.”

Wallace could recognize a totalitarian regime when he saw one. He had done so early on with Hitler. In 1945, he might have appointed the bellicose Ickes as secretary of war, which FDR had considered doing in 1940. Wallace might have pushed immediately in 1946 to develop a thermonuclear weapon, rather than wait until 1950, as actually occurred. (His estimates of R&D timelines for atomic development were uncanny.) And a President Wallace might also have bonded by autumn 1945, as did Ickes, with Britain’s daunting foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, who was set for war with Stalin — irrespective of the United States — over Iran in 1946 and Berlin in 1948.

Leave aside the “counterfactuals,” Wallace as VP and then as Commerce secretary, dreaded a resurgent Depression, as did FDR and then Harry Truman. Nonetheless, Steil singles out Wallace’s “gloomy, hectoring rhetoric” about the Depression’s expected return, and he speculates that Wallace “may have believed this dark warning, but he may also have been trying simply to reclaim his lost relevance on economic policy.” A reader wouldn’t know that Henry Wallace’s forecasting reflected the consensus opinion among experts. For instance, MIT economist Paul Samuelson offered his own “dark warning” of a postwar depression.

The World That Wasn’t is dated, as well, in its grasp of the early Cold War. After Japan’s defeat, we are to believe, the sprawling British empire gave up being a global imperial power. Thus, a rich, confident, well-armed America undertook leadership of the West. This notion assumes that voters beyond the better drawing rooms of the Northeast coast suddenly dropped their prewar insularity — and their fears of an imperiled economy — to have America become the world’s policeman.

In fact, U.S. forces demobilized immediately. Despite the atomic bomb, Americans recognized their overseas capabilities to be limited. The country in which Wallace was a private citizen after September 1946 had far less agency than is commonly believed. Only in 1956, a decade later, would Vice President Richard Nixon assert, speaking for Dwight Eisenhower, that the United States had finally “taken over the foreign policy leadership of the free world.” Meanwhile, from 1946 to 1951, a banged-up, yet determined imperial Britain — as embodied by Ernest Bevin — was shaping all too many key U.S. decisions.

Wallace had reason to worry about Britain’s postwar designs, as had FDR, and about the skill of its Foreign Office, which had long alarmed Roosevelt, too. In contrast to Britain’s expertise and focus,

Wallace opposed the Truman Doctrine in March 1947, to be sure. There were reasons, which are clear today. For better or worse, Britain wasn’t remotely considering a “global retrenchment,” as Steil believes. Contrary to the view in panic-stricken Washington, Bevin had no intention to withdraw 40,000 troops from Greece, where they were upholding a quasi-fascist monarchy against communist-backed rebels. Saying so to Washington was a bluff to get U.S. support.

Sure enough, the Americans stormed in with checkbooks and military advisors. Unthinkingly, Washington pledged to assist “free peoples” in their struggles against “terror” and “terrorist activities” — and not for the last time.

Wallace was spot-on to charge that “the president had allied himself with ‘fascists’” in Greece, and to predict that, in time, such emergency-driven responses would “bankrupt us morally.” Soon, for instance, the United States would be sponsoring France’s colonial war in Vietnam. The British, in turn, could redeploy their bulked-up Mediterranean forces to uphold imperial interests in the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia, besides.

Similarly, Steil reviles Henry Wallace for challenging the Marshall Plan, which had been proposed that June. In fact, Treasury Secretary John Snyder stopped this initiative cold within two weeks of Secretary of State George Marshall’s famous speech at Harvard.

Truman had to referee between Marshall and John Snyder, who was the administration’s most powerful figure from beginning to end, other than the president himself. A much-constrained Marshall Plan would proceed, yet it never met Congress’s key requirement of compelling the recipients of U.S. largesse to combine themselves into a strong, self-reliant European federation. Bevin vetoed that American dream.

Case by case, there were credible reasons for Henry Wallace, like other Americans on the left and right — and within government, like Secretary Snyder — to worry about the administration’s slapdash handling of foreign affairs.

Elsewhere, Benn Steil has written capably about the world’s postwar terrain. When he is addressing Wallace, however, his interpretations again become eccentric. Why believe that Stalin “must have” valued Wallace as a Soviet “stooge”? Or that Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet ambassador to the UN by 1948, “must have” been shocked by Wallace’s “breathtaking conceit”? Or that Wallace spoke pro-Soviet “code” (allegedly, four times) when he called for U.S. non-interference in the domestic affairs of other nations?

Steil devotes the last five chapters of this long book to Wallace as commerce secretary and then to Wallace as a speechifying private citizen. Commerce secretaries and ousted politicians are unlikely to have the fate of the world in their hands. Even

Steil is generous in his acknowledgements at the end of The World That Wasn’t. He thanks a Council on Foreign Relations study group of policy experts and scholars (“pedigreed historians”) for refining his work. Yet no one involved with this project seems to have advised the author on how the “collective leadership” of the Roosevelt administration worked, nor on the clout which the British superpower exercised after World War II. Both issues are vital to placing Wallace in the context of his times.

Nor does anyone in the study group appear to be an entrepreneur, and only one scientist is included among these dozen authorities. It’s a lack of perspective that helps explain how Henry Wallace can be so seriously misgauged.

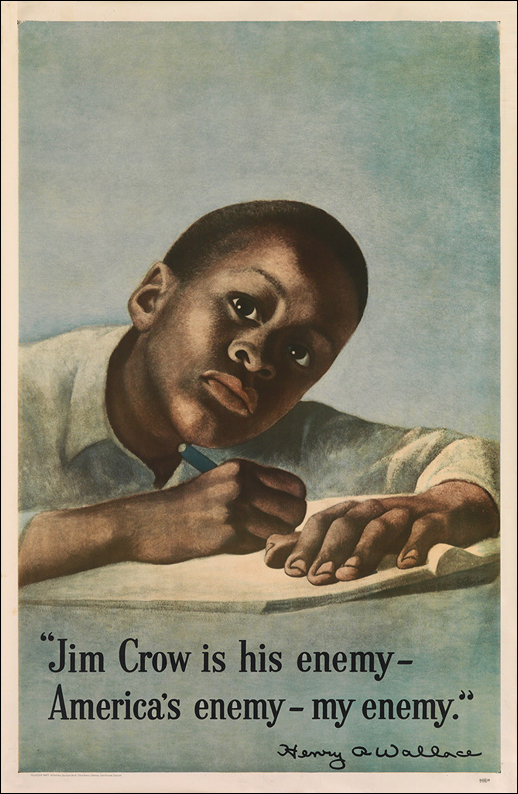

All involved with the Council on Foreign Relations project have spent an enormous effort examining Wallace’s 16-year “blip” in politics. Except, in the end, Wallace did indeed shape the so-called American Century: he helped to create a more abundant world, and also a world in which the United States had to attempt to live up to its ideals, as in his championing of civil rights.

In the end, Wallace did indeed shape the so-called American Century: he helped to create a more abundant world, and also a world in which the United States had to attempt to live up to its ideals, as in his championing of civil rights.

Even before starting his political journey in 1933, Wallace had taken steps that would lessen hunger and privation—in Eurasia, Africa, Latin America—through better agriculture. Human progress has been advanced by sustainable agriculture and global food security; as Wallace understood, such achievements deliver their own political benefits. Ultimately, it is Wallace’s impact upon science and enterprise that is profound, and makes his life worthy of an epitaph by Swift:

“Greater than kings and warriors is the man who has made two blades of grass grow where one grew before.”