Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 2

Editor's Note: Michael Wolraich is a journalist and author based in New York City. The following was adapted and condensed from his recent book, The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age.

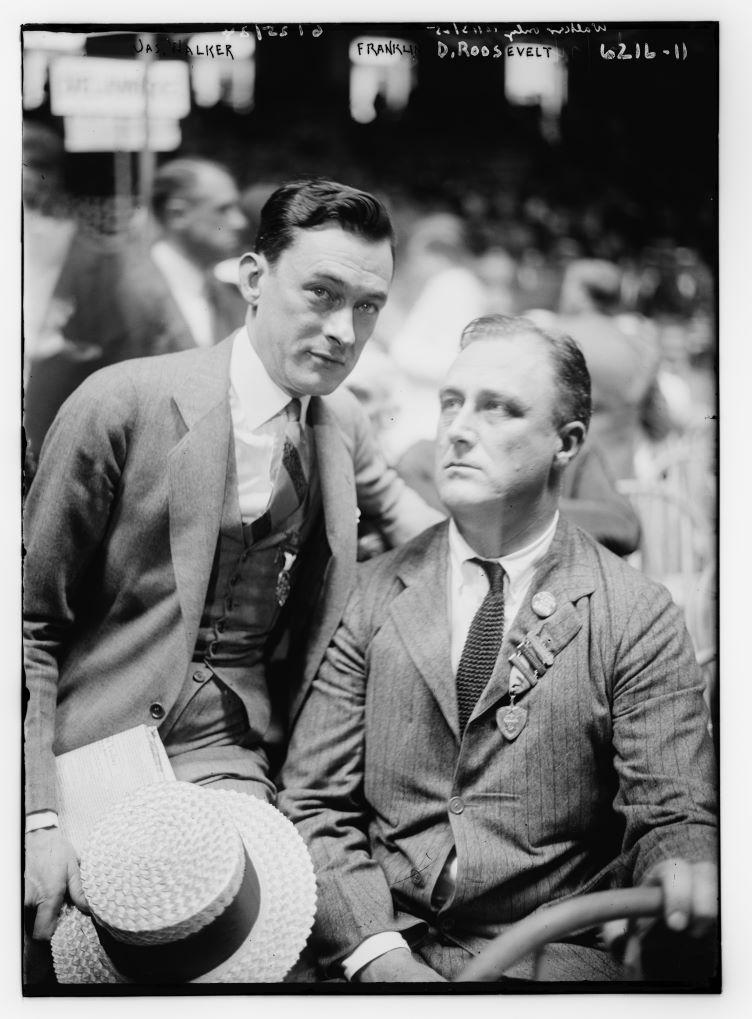

In the summer of 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then governor of New York, faced a dilemma. His presidential ambitions depended on a precarious alliance with Tammany Hall, the political machine that ruled New York City. Though eager to separate himself from the corrupt Tammany bosses, he needed their support to win his home state, the largest in the nation.

Two years earlier, he’d made a show of independence by initiating a limited state investigation into allegations of bribery by city officials. But the man he chose to lead the investigation, an imperious former judge named Samuel Seabury, uncovered something more sinister—a conspiracy to frame innocent women for prostitution. After one of Seabury’s witnesses, Vivian Gordon, was murdered, outraged New Yorkers demanded a full investigation of Tammany Hall.

Bowing to the political pressure, FDR reluctantly expanded Samuel Seabury’s authority. With his new powers, the tenacious investigator pursued the trail of graft up the political hierarchy, ultimately uncovering a million-dollar slush fund controlled by New York City’s flamboyant, wise-cracking mayor, Jimmy Walker.

Seabury’s stunning allegations magnified Roosevelt’s predicament. As governor, he had the authority to remove Walker for corruption, but deposing the popular mayor would infuriate Tammany’s bosses. He deferred his decision until after the Democratic national convention in Chicago, which allowed him to secure enough Tammany delegates to win the presidential nomination. But, when he returned to Albany, he could no longer avoid the predicament.

Over the next few weeks, Roosevelt received a flood of entreaties and unsolicited advice about the Walker problem. Some warned that, if he removed the mayor, he would certainly lose New York and likely Massachusetts, New Jersey, Illinois, and Connecticut. Others insisted that, if he didn’t remove Walker, he’d lose independents and progressive Republicans, which could jeopardize the western states. Roosevelt’s campaign manager, Jim Farley, who counted Walker as a personal friend, also urged FDR to spare the mayor.

In response to these conflicting appeals, Roosevelt vacillated. “On one occasion while talking over the subject,” his adviser, Raymond Moley, recalled, “Roosevelt said, half to me and half to himself, ‘How would it be if I let the little mayor off with a hell of a reprimand?’ Then suddenly, as if answering himself, Roosevelt said sharply, ‘No. That would be weak.’”