Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Editor's Note: Michael Mandelbaum is professor emeritus at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and the author most recently of The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How They Made History and the History They Made, a study of Wilson, Lenin, Hitler, Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gandhi, Ben-Gurion, and Mao, just published by Oxford University Press, from which this essay was adapted.

A century after he died in 1924, Woodrow Wilson remains a major presence in American foreign policy. One distinguished historian of American foreign relations, Robert W. Tucker, wrote that “in the history of America’s encounter with the world, Woodrow Wilson is the central figure.” According to another, George Herring, “Wilson towers above the landscape of modern American foreign policy like no other individual – the dominant personality, the seminal figure.” What accounts for this posthumous prominence?

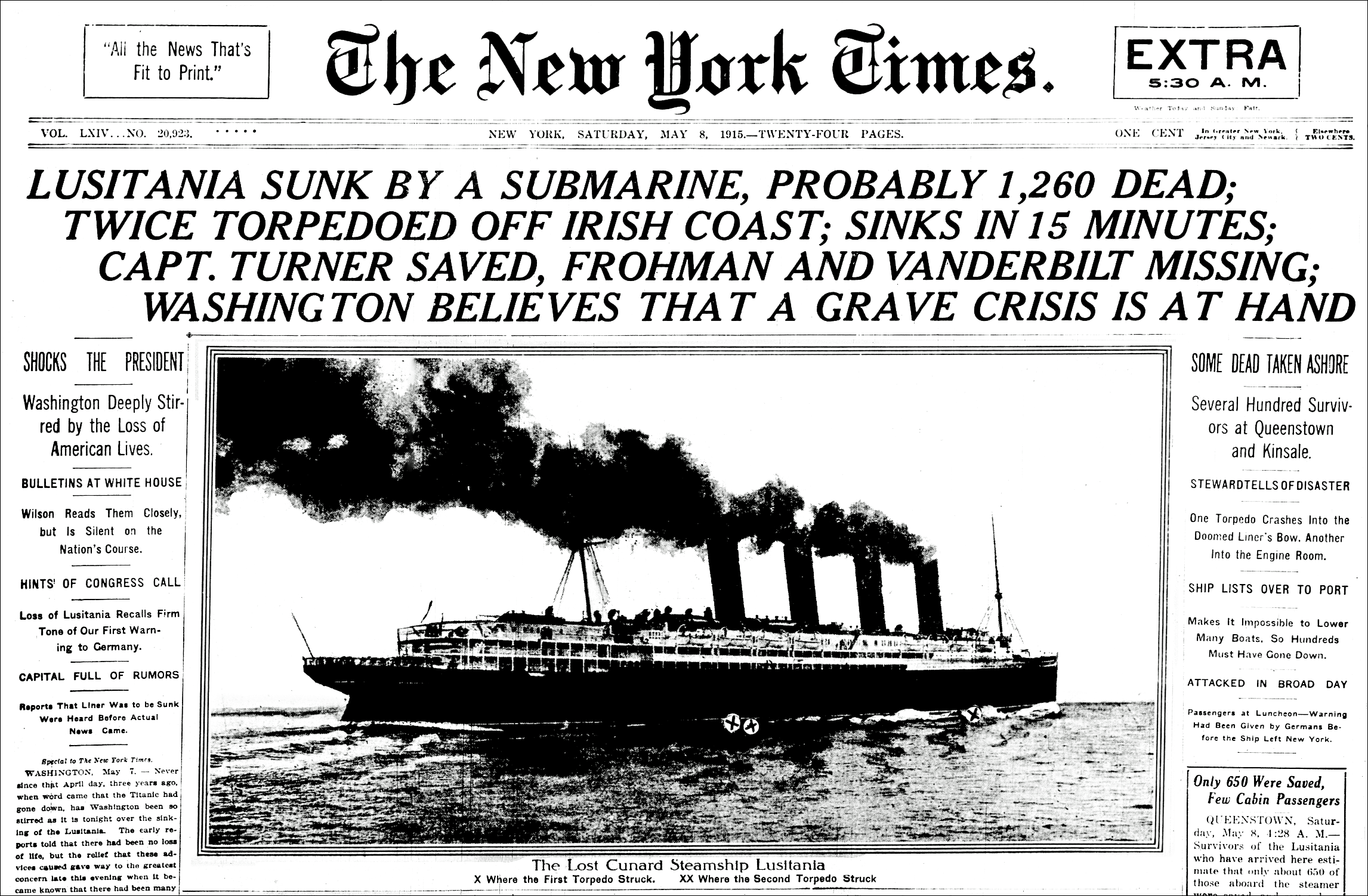

It does not stem from any resounding successes which American foreign policy achieved during his presidency. While he presided over the country’s participation in World War I, compared with other wartime presidents, he played a relatively minor role in that conflict. Unlike Franklin D. Roosevelt and World War II, Wilson himself did little to propel the United States into the war: the country was swept into it by public outrage at German submarine warfare. Also, unlike his successor, Wilson made no major wartime strategic decisions comparable to Roosevelt’s emphasis on the European, rather than the Pacific theater, or his designation of the timing of the Allied invasion of France in June, 1944.

In fact, American entry into the war may be seen as a significant, albeit inadvertent, failure of Wilson’s foreign policy. He wanted his country to remain strictly neutral, with the definition of neutrality including trade with both sides in the conflict. Britain used its naval superiority to try to starve Germany and Austria-Hungary into submission. Its blockade of enemy ports made American neutrality effectively pro-British.

In response, the Germans conducted submarine warfare in the Atlantic, which eventually pushed the United States into the war on Britain’s side.

Wilson did play a major role in the Peace Conference at