Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 71, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 71, Issue 2

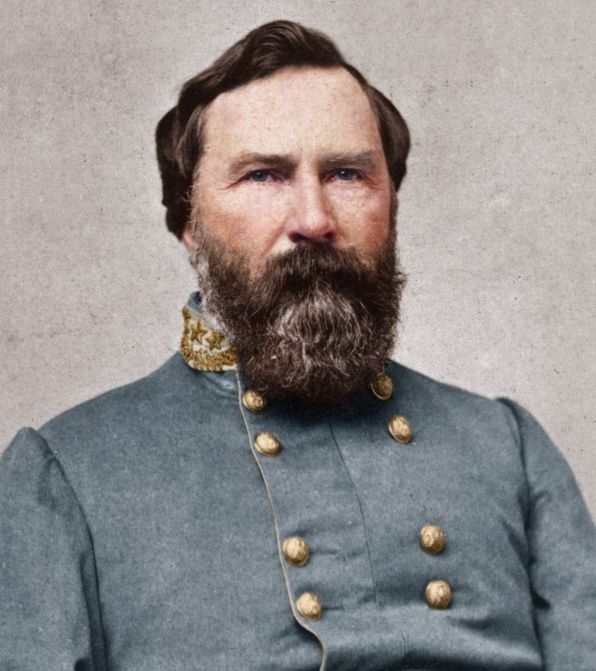

Editor’s Note: Elizabeth R. Varon is a professor of American History at the University of Virginia. She recently published a landmark biography of one of the Confederacy’s most intriguing military leaders, Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South, from which portions of this essay were adapted.

James Longstreet was one of the most respected and tenacious generals in the Confederate Army, the right hand of Robert E. Lee, who called him his “Old War Horse.” There were many good reasons for that moniker. Longstreet played a critical role in the Seven Days Battle, driving George McClellan’s army from Richmond, and then routed the Union at the Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas. At Antietam, another Confederate officer said Longsteet fought “like a man god.” Later he was a central leader at Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, the Wilderness, Petersburg, and Appomattox Court House.

After the war, a Federal grand jury indicted Longstreet for high treason because of his role as a wartime leader. President Andrew Johnson refused to pardon him, telling the former general: “There are three persons of the South who can never receive amnesty: Mr. Davis, General Lee, and yourself. You have given the Union cause too much trouble.” But Ulysses S. Grant interceded for his old friend from their days at West Point, and Longstreet was eventually paroled. He settled in New Orleans.

Then came one of the most remarkable about-faces in American history. Longstreet became to support Reconstruction and voting rights for black men, and joined the integrated post-war government. In March, April, and June 1867, he published four letters expressing his support for Congress’s newly announced program of Reconstruction. That legislation was a dramatic turning point in the nation’s history; it was also a crossroads for Longstreet, who, in the spring of 1867, very consciously chose a different path from that of most former Confederates.

His letters two years after the South’s defeat changed the course of his life forever. In writing them, this icon of the rebel cause chose not only to weigh in on national policy, but to wade into the turbulent waters of Louisiana’s highly factionalized politics. Divisions there dated back to the wartime occupation of New Orleans and the surrounding southeastern parishes by the federal army in the spring of 1862.

The Lincoln administration regarded the state as a promising test case for a policy of amnesty that would draw Southerners back into the Union. New Orleans was the South’s largest, wealthiest city. It also had a unique blend of