Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

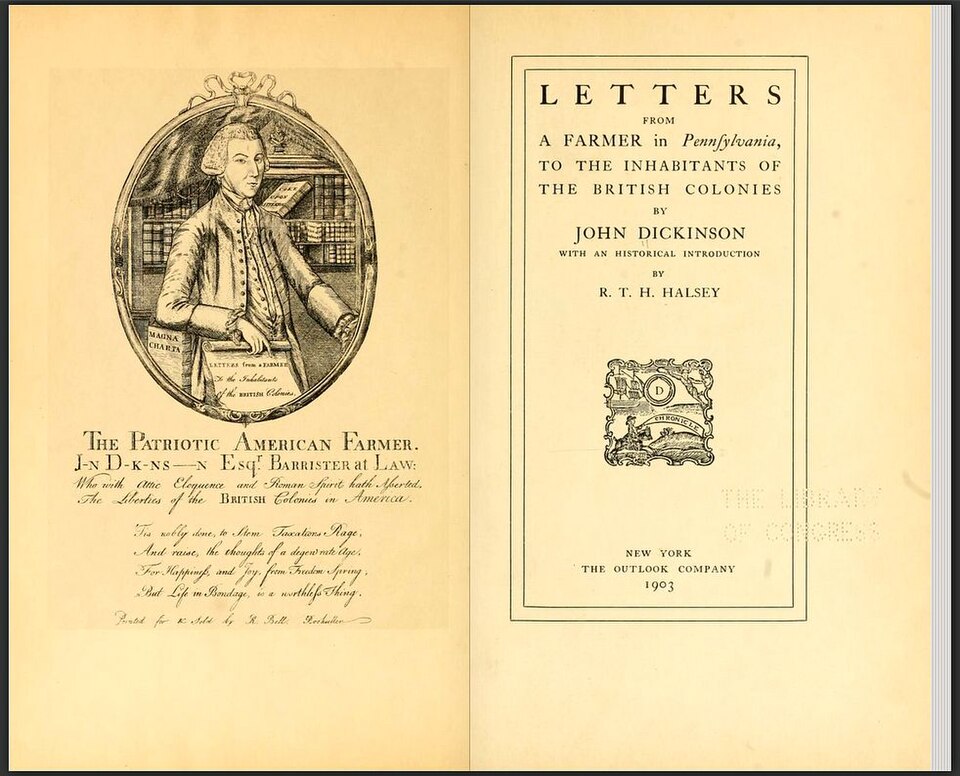

Editor's Note: Jane E. Calvert is the founding director and chief editor of the John Dickinson Writings Project. She is also the author of the first complete biography of Dickinson, Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson, which won the 2025 James Kirby Martin History Prize and is a finalist for the Herbert J. Storing Prize and the George Washington Book Prize. The following essay is adapted from that book.

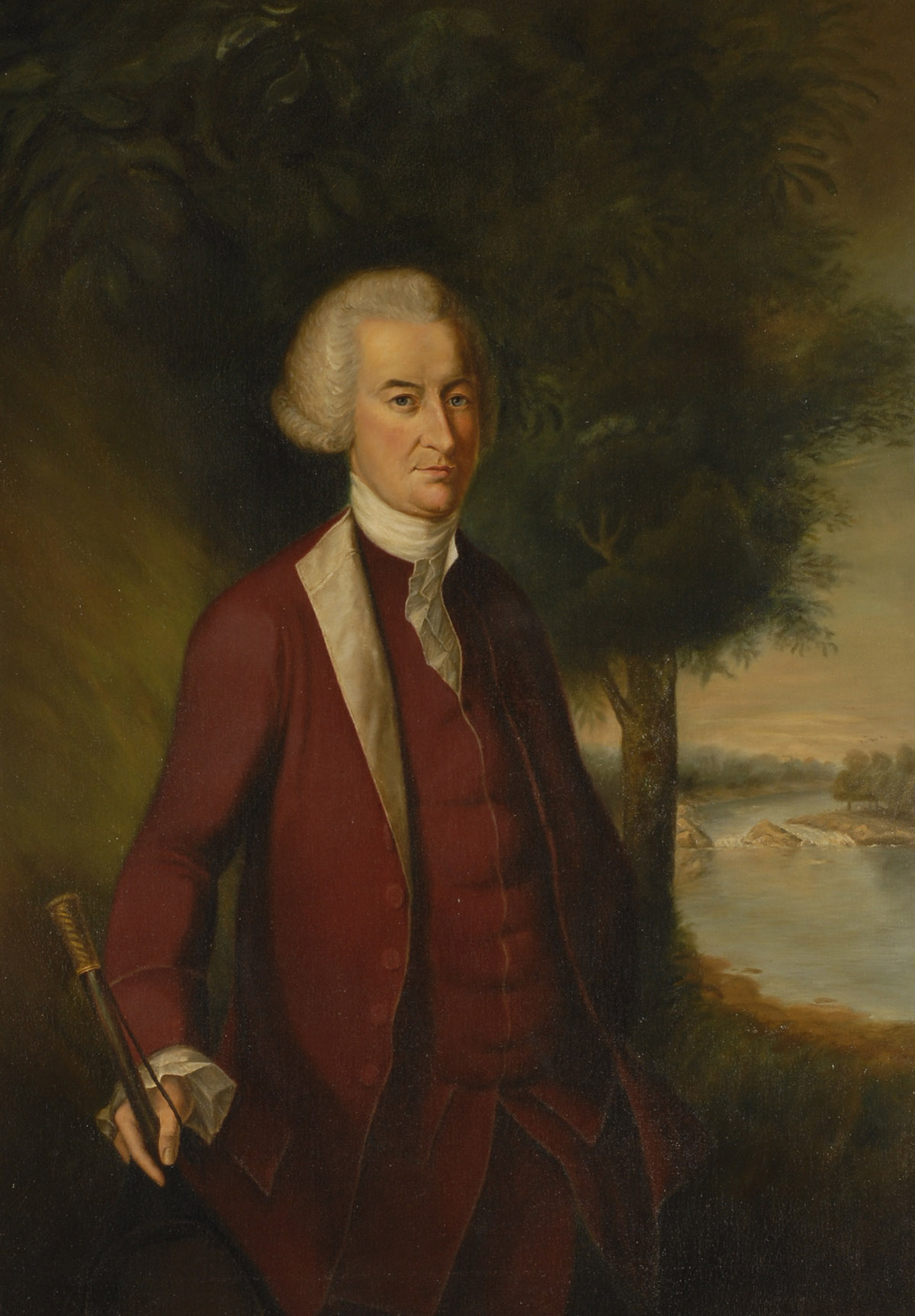

Most of America’s leading Founding Fathers are familiar to Americans: George Washington is the “Father of Our Country.” James Madison is the “Father of the Constitution.” John Adams is the “Atlas of Independence,” while Thomas Jefferson is the “Father of the Declaration of Independence.” Benjamin Franklin, the “First American,” is the wise embodiment of American ingenuity. Alexander Hamilton is the plucky immigrant who established our economic system.

Although some of these men have become controversial in recent years, these are the “Big Six” whom most Americans know and revere. But there is a seventh. And he is perhaps the most important Founder for us now, in this politically polarized moment. His name is John Dickinson.

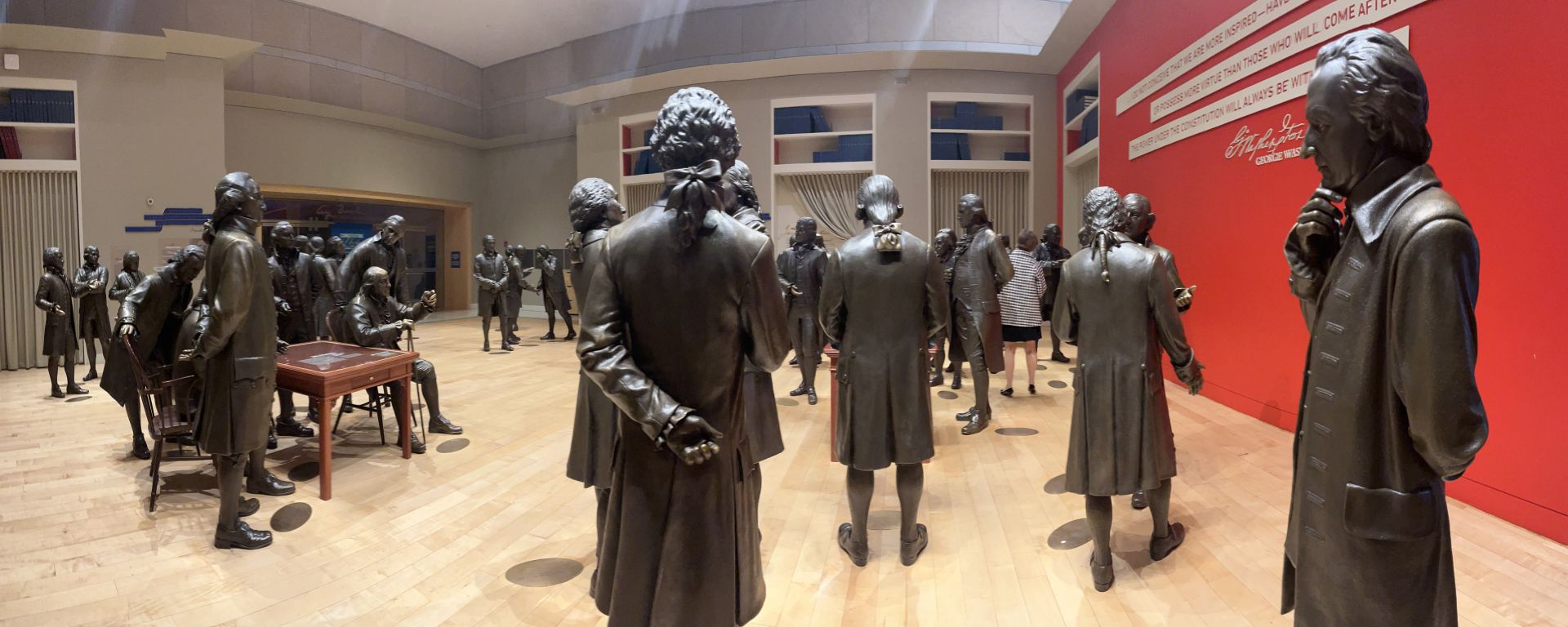

In Signers’ Hall at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, the statue of Dickinson stands alone in a corner, hand pensively on chin, apart from the action of the Federal Convention. The clear message is that he was too reserved, or perhaps too timid, to engage. He appears to be modeled on the Roman general Fabius, called “the delayer” for his caution in battle.

This is how Americans think of Dickinson—if they think of him. Alternatively, they might imagine him in the manner of the musical 1776, strutting across a stage, ever to the right, never to the left, with ruffles aflutter, singing jubilantly about his conservatism. There he at least possesses the virtue of energy. Or they could imagine him as HBO’s pale, sweaty, scowling disbeliever in the American cause, opposite a stalwart John Adams. But none of these images of him is accurate.

For more than two