Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 1

Authors: Todd Belt

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Todd Belt is a Professor and Director of the Political Management Master's Program at George Washington University. He is the co-author of four books, including The Presidency and Domestic Policy: Comparing Leadership Styles, FDR to Biden, the third edition of which was released in 2024.

For the past 25 years, I have taught courses on the U.S. presidency, emphasizing a fundamental principle: the president is not a king. While most of Americans don’t want a king, they do want a more active chief executive — and a more effective government.

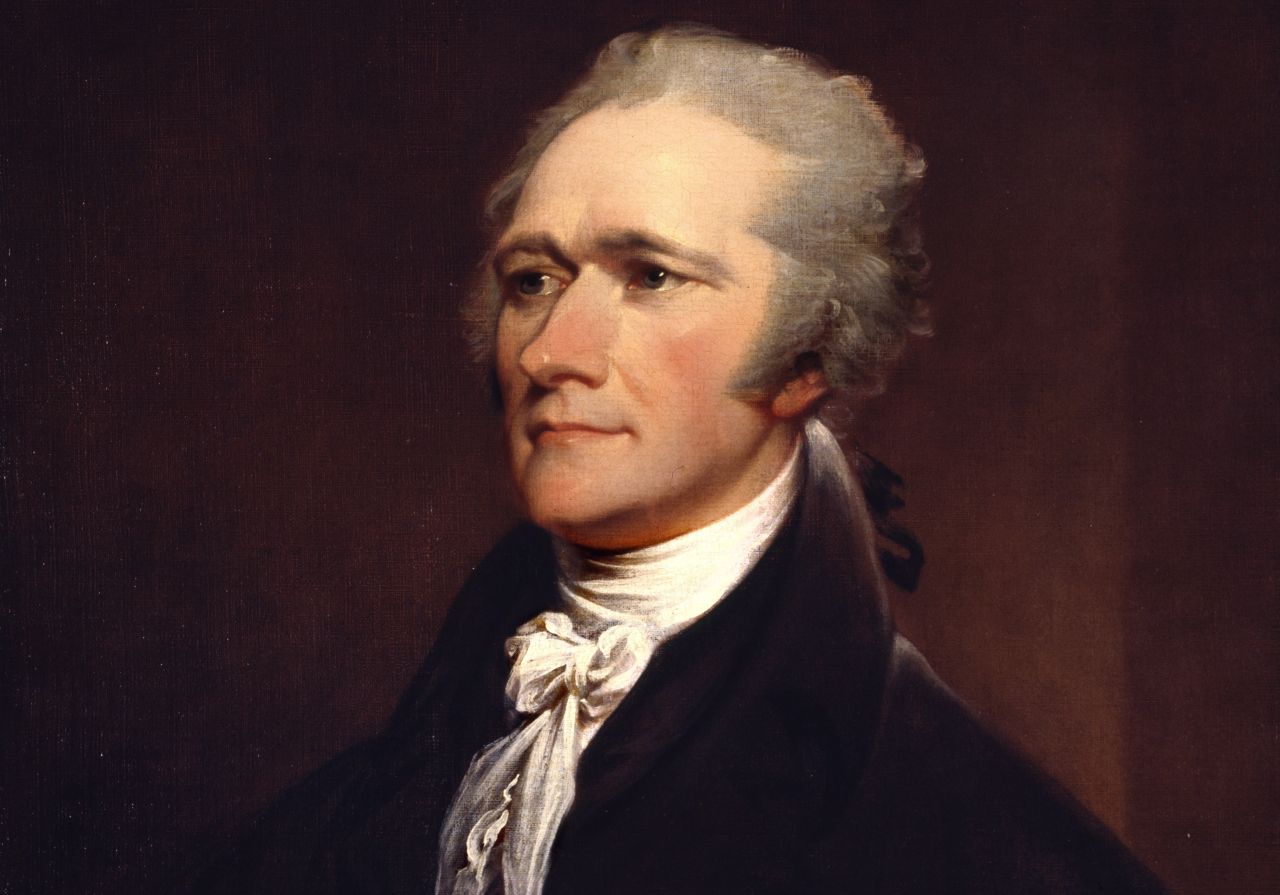

As Alexander Hamilton noted in Federalist 70, the energy of government is in the executive (branch), and that is where we expect it to originate. In popular culture, we often laud presidents who find a way to get things done. In the TV show House of Cards, for example, President Frank Underwood resorts to emergency powers to get his employment program (called AmWorks) implemented.

Some see our governmental system as sclerotic and in need of a push. Others are concerned about consequences that could result if pushed too hard. That’s why it is crucial for us to consider what history reveals about presidents who have pushed the system and some of the tools they have used – from Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus to Franklin Roosevelt’s court-packing plan to Richard Nixon’s assertion of executive privilege. More recently, Donald Trump has tested the limits of executive power in unprecedented ways.

Understanding these moments in history helps us navigate our country’s ongoing tension between strong leadership and the constitutional limits designed to prevent an imperial presidency.

The president’s powers are often unclear, with limited direct constitutional authority. Article II of the Constitution, which addresses the presidency, was written to be deliberately vague. The authors of the Constitution knew they wanted a president because the Articles of Confederation weren’t working. They needed a head of state who could exert executive power. But they also knew they didn’t want a king. To strike a balance, they left it largely up to the discretion of the office holders to define the office over time.

We have a system of government with checks and balances, shared powers, and federalism (the division of the powers between the states and the federal government). As Congress has given away more and more power to the presidency, states have increasingly used the federal courts to block presidents’ actions. Trump’s quick use of executive orders in the first week of his second term generated numerous and nearly immediate challenges in the federal courts.

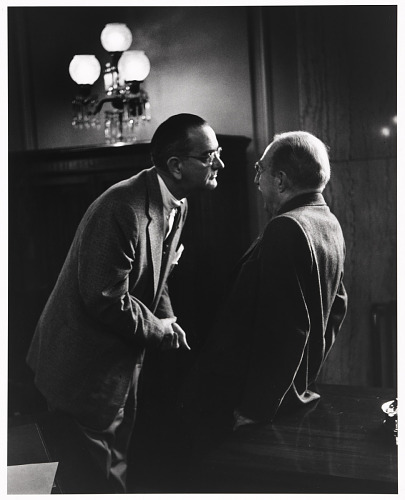

All of these potential roadblocks can make things difficult for a president trying to exert power. As presidential scholar Richard Neustadt noted, unlike the specific authority grated to congress in the Constitution, a president’s true influence lies in the ability to persuade, achieved through bargaining and even personal pressure. A perfect example is the famous photo of Lyndon B. Johnson’s giving his signature “treatment” to Senator Theodore Green of Rhode Island, a display of power and persuasion from Johnson’s days as Senate majority leader. LBJ continued to use his powers of persuasion in the White House to push his legislative agenda effectively. Other less direct avenues for persuasion and pressure exist through mass media (exemplified by Ronald Reagan) and social media (exemplified by Donald Trump), whereby the public is rallied to pressure the president’s targets. We know that presidents face different levels of opportunity. To use a baseball metaphor, presidents aren’t starting pitchers; they are relief pitchers who come in midway in a game facing different situations. Barack Obama inherited two wars. Joe Biden inherited a COVID pandemic. President Donald Trump inherited two crises, one in Ukraine and one in Israel. Opportunities for presidents to leverage their power comes in various forms. The mood of the public is one factor that shapes their opportunities. Sometimes people want the president to do something. When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933 during the Great Depression, for example, many Americans were desperate for government action. At other times, the public has wanted presidents not to do something. In 1980, for instance, voters elected Ronald Reagan, who championed limited government and deregulation. Back then, government was seen by many as the problem, not the solution. In considering President Trump’s opportunities in his second term, it’s important to recognize that the public mood in the election was one of change. In terms of public support, he claims an electoral mandate for change, having won all seven swing states, but he only secured 49.8% of the popular vote. It’s possible that President Trump is not merely overstating his mandate but also misreading it, since it remains unclear whether his voters supported some of his most radical policy priorities since taking office, such as acquiring Greenland or the Panama Canal Zone. If presidents can bring in new members of Congress from their own party and secure a favorable balance of power in the House and the Senate, those opportunities can significantly enhance

In terms of promising issues for Donald Trump in his second term, Congress quickly passed the Laken Riley Act, which authorized federal authorities to detain illegal immigrants who have committed certain crimes. So, the President could take a very quick victory lap with that. Overall, the legislative setting is favorable for Donald Trump, although he didn’t help himself by selecting three House members for his cabinet, reducing his party’s margin to two in the House. A further obstacle to President Trump’s opportunity to implement his budget priorities and tax cuts is the resolve of House members who previously challenged Speaker Kevin McCarthy and Speaker Mike Johnson to closely scrutinize federal spending. These members want budget cuts, and as they delve into President Trump’s budget package, the process could become contentious. As the March government spending deadline approaches, these House members don’t want to rely on any more temporary extensions. Meanwhile, Speaker Johnson has had to make a series of promises to these Republicans, who believe that they were sent to Washington D.C. specifically to be disruptive to what they perceive to be an unresponsive government. But working in President Trump’s favor is his influence over Congress through the potential to recruit and promote challengers to members of his own party in future primary elections. An example is Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa, who faced such “primary threat” pressure to vote in favor of the nomination of Pete Hegseth, the President’s nominee to lead the Department of Defense, after she initially refused to commit to supporting Hegseth. A president’s resources, including economic conditions, can also affect their power. Members of Congress may resist spending and raise budget deficit concerns, limiting presidential action. Although counterintuitive, presidents generally have more power when the economy is bad, rather than in times of prosperity. A struggling economy creates opportunities for a president when they enter office because people are looking to them for change and other political actors are more likely to defer to the president for decisive action. In terms of President Trump’s resources, the country’s economic conditions and the high federal budget deficit, both of which he wants to address, are a challenge to his power. Trump inherited an economy that was good by many metrics (such as growth and unemployment), but poor in terms of inflation, which is notoriously difficult to tame except by measures that stunt growth. Funding of Trump’s proposed tax cuts while offsetting the revenue losses will be incredibly difficult if he is to reduce deficits,

As mentioned above, President Trump faces two foreign policy crises in Ukraine and Israel. These will divert time and energy from his preferred domestic policy goals. Much depends upon the president’s skill level, including the quality of the people they recruit to work for them. To get things done, a president needs to cultivate four skills in particular. First, the choice of advisors is absolutely critical in shaping options and decisions. When considering effective presidential advisory processes, FDR’s “brain trust” that helped craft the New Deal or President John F. Kennedy’s “best and the brightest” inner circle often come to mind. At the same time, as Kennedy learned through the Bay of Pigs fiasco, when few in his inner circle challenged the feasibility of the invasion, presidents need people willing to challenge their assumptions. Advisers must be willing to shoot holes in ideas; an inner circle full of “yes” people can cause potentially disastrous mistakes. As for President Trump’s advisers in his second term, there could be areas of concern. In President Trump’s early administration during his first term, he was surrounded by people he didn’t know, didn’t trust, and who told him “no” more often than he wanted to hear. In his second term, he is prizing loyalty from many of his nominees as well as their ability to defend him effectively in the media. Thus, there is the potential that some advice he’s receiving from some advisors raises the risk that certain executive orders are unconstitutional. The second key skill is deals with administration: selecting and directing staffing in the executive branch. As hirer-in-chief, the president must fill 4,000 executive branch positions, making selecting and managing those personnel critical to carrying out presidential policies. As the saying goes, “personnel is policy,” since people appointed by the president shape what government does and how effective it is. And of course, the president’s congressional leadership is another skill, as we have seen with LBJ’s active engagement with Congress. During President Trump’s first term, he did not engage in significant congressional leadership, holding very few meetings with members of Congress and leaving most engagement to others. But this term will be a different Trump presidency in terms of his relations with Congress. He is already meeting with members of Congress and will continue to be more active in engaging with Congress because he knows that any legislation it passes will last longer than his executive orders. The fourth important skill a president must exert is public leadership. A president with good public leadership

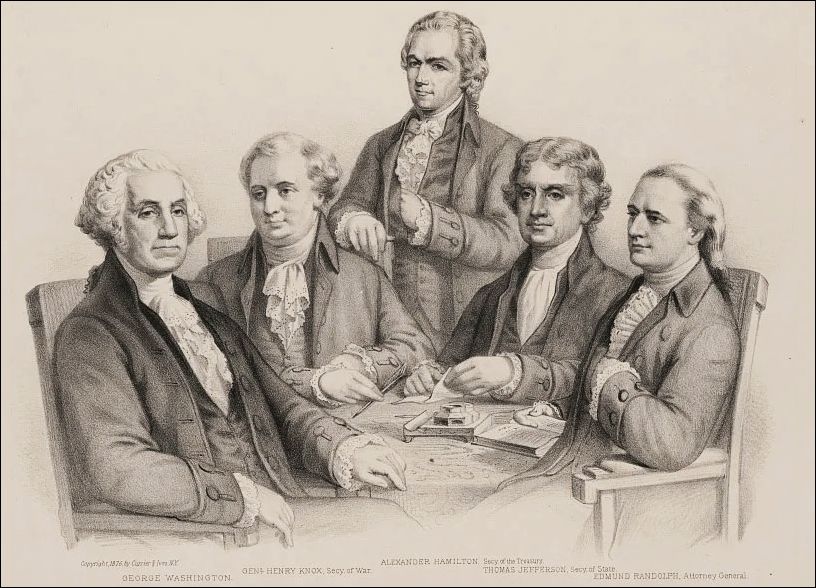

In addition to these skills, it is also important to understand the perspective and character that presidents bring to the office. James David Barber’s book, The Presidential Character: Predicting Performance in the White House, examined different types of presidents, based upon their psychological profile. Are they active-passive? Are they positive or negative in their outlook and in how they exert the job? Usually, presidents who find new ways of getting things done tend to be adaptive – they approach the office with a very positive view of what they can do for the country and are able to be willing and flexible. But there are also active presidents who have more of a negative perception. They see enemies everywhere, and they become more compulsive in their approach to the presidency. They will continue to push their power forward, instead of trying to find new, lasting ways to exert presidential power. Many historians think of Richard Nixon in this regard. Our first president, George Washington, helped structure what we think of the presidency through what he called “prudence.” He liked to say, “I walk on untrodden ground” because he knew that he would set precedents and establish the norms for the office. These included the development of the cabinet and the idea that the president can propose legislation. Importantly, the “Decision of 1789” established the president as having the power to unilaterally fire executive branch officials. When the Constitution was first written, Senate confirmation for a number of high-level officials was required. Senators thought their “advice and consent” on these positions extended to removal from office. Congress ultimately affirmed that the president has the unilateral right to remove executive officials without Senate approval. This greatly augmented the power of the president and led to Andrew Jackson’s “spoils system” approach of wiping out and replacing federal employees. Congress has since put requirements on removal of officials appointed to certain semi-independent agencies, as well as terms of office that don't overlap with the president’s term of office (such as the Federal Reserve Board). History provides numerous examples of how presidential power can be expanded. The Insurrection Act of 1807 allows the president to use federal troops to enforce federal law in cases of insurrection or obstruction of federal law, or when states are unable to enforce the law properly. Unfortunately, key terms like “insurrection” and “rebellion” were left undefined. The Act has been invoked several times since, most recently by President George H.W. Bush during Hurricane Hugo in 1989 and the 1992 Los Angeles riots. President Trump reportedly has threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to use the military as a domestic police force (active military have recently only served in a support role for local police). During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus, the doctrine of which guarantees an individual’s right to challenge their detention by appearing in court. Lincoln used it in a limited way for those he considered enemies of the union. It was challenged immediately, and the Supreme Court ruled that only Congress could give the president that power. As a result, Congress passed legislation authorizing Lincoln to do so, and he later exercised that power more broadly. This is an example of taking a small, limited action, then using the legal challenge as an opportunity to make a public case defending the need for an action before the Supreme Court. The court then adjudicates how Congress can give the president the desired power, and then Congress does just that. This approach could significantly influence how President Trump navigates legal and constitutional boundaries. During the Biden Administration, there was talk about “court packing” – adding justices to address the six-three ideological split in the U.S. Supreme Court. Of course, FDR believed he could have more support from the Supreme Court after his landslide re-election in 1936 if he packed it with justices who were more amenable to his decisions. The idea turned out to be highly unpopular, and Congress never pursued it, as it fell under congressional. However, President Trump might consider the idea if some of his actions are struck down as unconstitutional. The controversial internment of Japanese Americans during World War II authorized by Executive Order 9066 was upheld by the Supreme Court in the landmark 1944 Korematsu v. United States case. The rationale came from the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a component of the Alien and Sedition Acts. Some provisions of the Acts expired over time, others did not. President Trump has designated foreign drug cartels as terrorist organizations, and analysts suggest that some of the language that he has used suggests he might be using the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as authority to exert more presidential power in this regard. The presidential use of war powers has been

Over time, presidents have sought authorization under the War Powers Act. In emergency situations, presidents are allowed to commit forces for 30 days, plus an additional 60 days for an orderly withdrawal. In this case, they must consult “in every possible instance before” introducing forces. Alternatively, presidents can seek direct statutory authority from Congress for the use of force. Presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush used this provision, and Barack Obama continued to use the authority provided to his predecessor. We also saw Barack Obama use force in ways that seemed to be in violation of the War Powers Resolution. One was use of force in Libya in during the NATO-led operation against Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. Keep in mind that President Obama didn’t call that an “intervention” or the “use of force.” It was termed a “kinetic military operation,” which could seem to be merely a rhetorical device were it not involving life and death. We’ve seen Donald Trump refer to illegal immigration as an “invasion,” which may foreshadow a similar approach. It appears that President Trump’s advisors have informed him that he has impoundment power to stop congressionally authorized expenditures. This position is at odds with the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, which stipulates that the president does not have the power to impound money. Only Congress has the power of the purse, and the president must obtain Congressional approval to do so. But Trump may ignore and/or challenge the Act to override spending plans he feels are unnecessary or wasteful. Finally, there is the issue of agreements and treaties. In recent history, presidents have redefined executive power by labeling certain international commitments as “agreements” rather than “treaties” in order to bypass Senate ratification, which requires a super majority. That can be difficult to achieve in a closely divided Senate. So, President Obama referred to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal as an “executive agreement.” But a downside to executive agreements is they are easily terminated by a successor because they don’t have the full weight of the Constitution behind them that a Senate-approved treaty does. Trump has removed the US from numerous agreements and may make use of this “agreement” process to fast-track those of his own through the Senate. During Richard Nixon’s administration, we saw the president sending troops to Laos and Cambodia and carrying

We’ve seen a ceding of authority from Congress to the presidency in foreign policy, especially in allowing the president to make international agreements. At the same time, foreign policy expertise among members of Congress has declined since the 1990s. There are a number of reasons for this. Over time, the Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees in the House as well as the Foreign Relations Committee in the Senate have held many fewer committee hearings, resulting in less supervision of the executive branch. There has been significantly more turnover in Congress and increased committee assignments, meaning that representatives have needed more breadth of expertise than depth. This poses a challenge for international affairs because depth of knowledge is needed in order to understand the complexities of world affairs. This has all worked to the advantage of the president. There was much concern about signing statements during President George W. Bush’s administration. Consider the Detainee Treatment Act, passed by Congress, which the president asserted did apply during wartime. Bush asserted the “unitary executive” theory in the signing statement – meaning that greater powers to the president accrue during time of war. In his first term, Donald Trump often claimed, “I have Article II that allows me to do what I want.” What he was referring to was the unitary executive theory that the “take care” clause of the Constitution provides him with expansive powers. The Supreme Court’s July 2024 decision significantly expanding presidential immunity further reinforces this rationale for his ability to act with fewer legal constraints than previous presidents. In terms of his electoral coalition, Donald Trump sees himself as bringing into the electorate a new group of white working-class voters who had previously been alienated by the dysfunction of a nonresponsive Washington. Trump didn’t get the most votes in 2016, but he got them in the right places by cobbling together this coalition. In 2024 he was able to rebuild his coalition, expanding it to include more working-class Hispanic voters, as

One approach that President Trump likes to take is to use emergency declarations to reprogram money. When a president issues an emergency declaration, it opens up 130 statutory provisions in the US code that give the president significantly more authority. The so-called legislative veto – where Congress overturns an executive order – is a check that Congress is supposed to have against the president for what it perceives to be falsely declared emergencies. In the 1983 Supreme Court case, Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha, the court ruled that the legislative veto required approval by both chambers of Congress, and that the president could veto the legislative veto, since it was ordinary legislation. This means that if Congress wants to override the president’s veto, it would take a two-thirds vote in both chambers. This means that once a president has asserted the power of an emergency declaration, it becomes much more difficult for Congress to check him. President Joe Biden extended the emergency declaration during the COVID pandemic to include the Higher Education Relief Opportunities For Students (HEROES) Act to forgive student loan debt. But the Supreme Court ruled in Biden v. Nebraska (2023) that this action went too far beyond the president’s emergency powers. It’s possible that Trump will consider invoking the National Emergencies Act. He has also considered using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) for his tariffs. Signed into law by President Jimmy Carter in 1977, the IEEPA gives the president the authority to regulate international commerce and financial transactions during a national emergency. President Trump has ignored statutory language in the past; for example, when he exerted certain emergency powers in his first term. He is disregarding it again in his second term, although there have been times where President Trump has unintentionally hindered his own progress in pursuing these actions due to omissions or oversights. In firing seventeen inspectors general, he was supposed to give a thirty-day notice to Congress. His failure to do so is being challenged in the courts. President Trump has ignored statutory language in imposing tariffs using the authority in the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This act which allows him to impose tariffs on imports that threaten the national security of the U.S., and in his first term

Old precedents, even from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, will be used by Trump as justification for some presidential actions. In pardoning the January 6th insurrectionists, President Trump referred to pardons issued by President Biden at the end of his term. And in some of his executive orders, he has referenced older historical precedents. In his first week, Donald Trump signed 36 executive orders, memoranda and proclamations – putting him on a record pace compared to previous presidents. One of these orders revoked 78 of Biden’s executive orders, so the breadth of action is staggering. So why such a fast start this time? President Trump learned from his mistakes in his previous term. The traditional method presidents use for executive orders when they come into office is a controlled process involving the Office of Management and Budget and the Department of Justice. This process helps to clarify these executive orders and provide a robust legal justification. Instead, this time the process has been conducted by a team of private lawyers prior to the president taking office. This way, he could issue them on the first day of his administration, as he had promised. However, the justifications, rationale, and clarity may make the orders subject to legal challenges since they may not be as robust as the traditional process. When thinking about what Trump will do, it is important to think about the historical precedents he adopts, the opportunities and limitations he faces, his skill level at governance, and his own personal proclivities. It’s probable that the president will resume building the U.S.-Mexico border wall. It was his biggest applause line when he first ran for office, and he will likely find the funds to complete more, if not all of it. He believes that the wall represents his follow-through on his signature campaign issue of immigration. Trump knows that immigration is key to holding together his constituency. This is one of the reasons he signed an executive order revoking birthright citizenship, in clear disregard of the 14th Amendment. This action was immediately challenged and temporarily struck down by a Reagan-appointed federal judge.

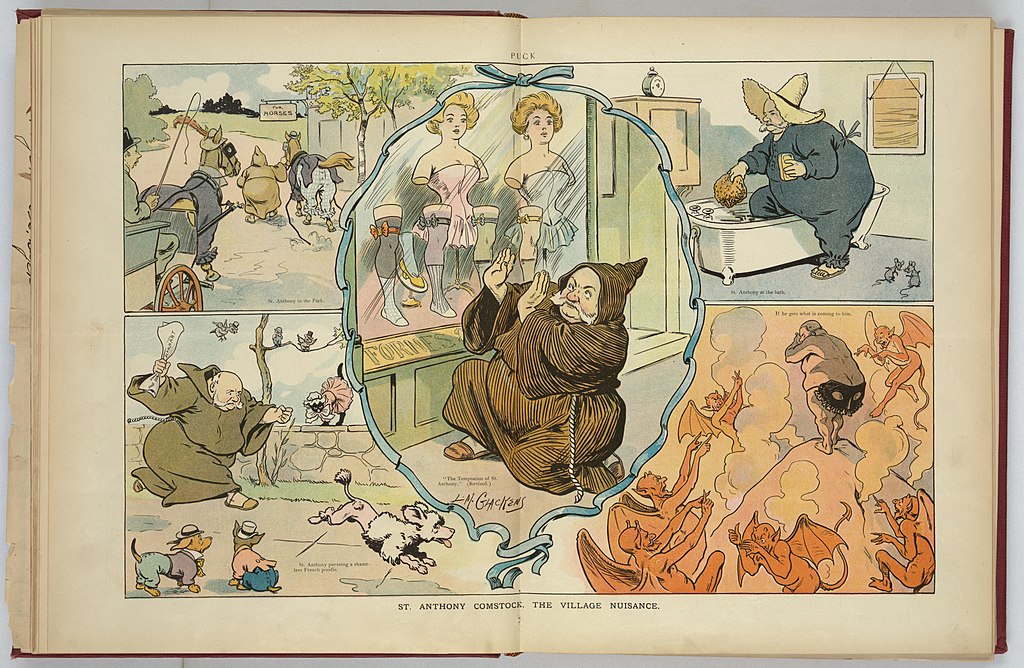

Presidents try to maintain their coalition so they can have a real power with Congress. As a consequence, it’s possible that, out of concern that he is losing some evangelical Christians who carried him to victory, President Trump will invoke the 1873 Comstock Act. This act prohibits the mailing of obscene materials, including contraceptives, abortion-related materials, and any items deemed “immoral.” While he pointed out to his coalition of evangelicals that he “gave” them the Supreme Court Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade, and that it should settle the abortion issue, many evangelicals are now saying they want additional action against abortion. President Trump will likely go after certain abortion drugs, including Mifepristone, and may support other measures to align with his coalition. President Trump’s executive order to temporarily pause Tik-Tok’s ban in the U.S. is another example of his disregard of statutory language. Trump claims that when Congress passed the legislation, it gave the president 90 days to make a deal. But the law actually says that the president can have 90 days if a deal is pending. But, in President Donald Trump’s mind, he had a deal and possessed the legal authority. This is similar to his assertion that he can declassify documents just by thinking about it. I would expect more of this sort of rhetorical sleight-of-hand in order to muddy the legal waters. There is a possibility that there will be military intervention in Mexico. As we saw, President Trump has been pushing the classification of foreign drug cartels as terrorists. That said, military action in Mexico will be extremely difficult, with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo vehemently opposed. Of course, as we have seen, there are constitutional limitations on a president, such as the 14th Amendment when it comes to birthright citizenship. States are already filing lawsuits citing the Constitution on a number of President Trump’s actions. But Donald Trump doesn’t follow normal procedures – he plows ahead. At the end of his first term, President Trump attempted to impose Schedule F reclassification, which turns more civil servants into presidential appointees, making it easier to hire and fire them. His action failed, but in his second term, he has moved forward with Schedule F again, which will produce more presidential appointees who are less subject to civil service protections. In his second term, one of President Trump’s first showdowns with an international leader was with Colombian President Gustavo Petro, who first stood up and then stood down on the issue of

What President Trump will build in the long run remains to be seen. But it’s important to remember that what he does now will set the tone for his successors. Many are waiting in the wings, but whether or not they can hold together his coalition remains to be seen. It is entirely possible that Trump's coalition has more to do with his personality than his policies.

Opportunity often shapes Presidencies

An important question is also perception: do the people around President Trump, and do members of Congress, believe he has that public support? And are they concerned about his level of support? Importantly, do sitting members of Congress believe the president’s level of support is particularly problematic for their electoral future? Effective processes depend on Presidential character and skill

Examples from history set the tone

Reviving the Imperial Presidency

Trump’s approaches to expanding authority

Likely actions that President Trump will take