Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 2

Authors: John Ferling

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 2

Editor’s Note: One of the leading historians of the American Revolution and Founding era, John Ferling is a professor emeritus at the University of West Georgia and the author of two dozen books. His most recent is a major, global reappraisal of the Revolutionary War on its 250th Anniversary, Shots Heard Round the World: America, Britain, and Europe in the Revolutionary War, from which portions of this essay were adapted.

America’s Revolutionary War might have been avoided, but it wasn’t, and the American insurgency might have been crushed within a year or so of fighting, but it wasn’t. What began as a civil war within the British Empire continued until it became a wider conflict involving nations in Europe and affecting peoples and countries far from Great Britain and North America. Long after the soldiers laid down their arms, future generations in America and in distant corners of the world were touched — sometimes favorably, sometimes adversely — by the American Revolution and the fallout from its war.

The stirrings that led to the conflagration were set in motion in the 1760s, when Great Britain embarked on a striking departure in its colonial policies. It was a multifaceted divergence that stepped on many toes, including those of the most powerful residents in the 13 North American colonies. Britain tightened its regulation of imperial trade, hoping to eliminate smuggling by urban merchants who trafficked in outlawed foreign commodities and sought to avoid paying duties on legitimate commerce. Imperial authorities also mandated a temporary halt to western migration beyond the Appalachian Mountains, antagonizing land speculators — mostly wealthy and influential colonists — and land-hungry farmers.

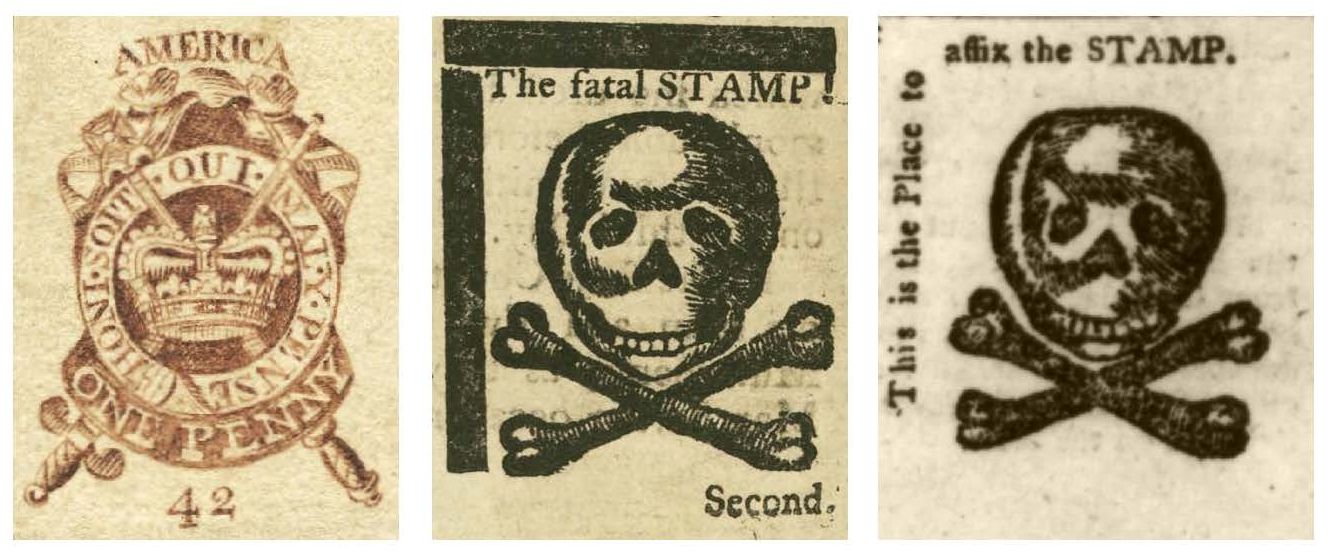

With the Stamp Act, in 1765, Parliament for the first time sought to levy taxes on its American subjects. It subsequently turned to other forms of taxation. To many colonists it seemed, as it did in 1774 to the Virginia planter and businessman George Washington, that Great Britain was pursuing “a Systematic ascertion of an arbitrary power” in violation of “the Laws & Constitution of their Country, & to violate the most essential & valuable rights of mankind.”

Many colonists harbored grievances other than those concerning regulations and taxes. Some people in some provinces were unhappy with having to pay tithes to the established Church of England. Ambitious colonists resented the fact-of-life limitations that faced them. Confronted with an unspoken but all-too-real second-class rank within the British Empire, aspiring colonists recognized that the door was closed to their sitting in Parliament, gaining ministerial and diplomatic posts, or rising to

Britain had fought three wars in the three-quarters of a century down to 1763, and the American colonists had been dragged into each conflict. Many colonists viewed these as Europe’s wars that were of little concern to them, and they were eager to escape the talons of faraway leaders who made the wars and expected the participation of the American colonists. Doubtless, too, there were a great many ordinary colonists such as Levi Preston, a farmer in Danvers, Massachusetts, who in 1775 expressed in crystal-clear terms what troubled him: “we had always governed ourselves and we always meant to,” but the British government “didn’t mean we should.”‘ Like Preston, a great many colonists thought the time had come for Americans to control their own destiny.

Widespread protests against Britain’s new colonial policies flared in the 1760s. Colonists remonstrated with petitions, pamphlets, economic boycotts, and sometimes violence. A succession of British governments during the next several years backed and filled. Some measures were repealed; others were recalibrated. However, Parliament held intransigently to the position that it possessed the power to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

In 1768, convinced that Massachusetts was the epicenter of the turmoil, London redeployed three regiments of its army from the western frontier to Boston to cope with the unrest. Long since convinced that standing armies were tools of oppression and toxic threats to liberty, some colonists interpreted the arrival of the troops in Boston as yet another indicator that the British government was in the clutches of brutish tyrants. There was talk of armed resistance when the British regiments landed in the city, but nothing came of it. In fact, tensions eased after 1770 when Britain again repealed some of its troubling legislation and removed most of its troops from Boston, housing them in barracks outside the city.

Tranquility coincided with the creation of a ministry head by Frederick, Lord North in 1770. In his late 30s when he became the prime minister, North was astute, witty, anything but haughty, and given his unflattering and uninspiring bearing — one observer described him as “booby-looking” – scarcely charismatic. He had sat in Parliament and the ministry for years. Economic matters were his primary concern. Colonial affairs were of secondary interest to him, and during his early years as prime minister he sought to keep the Americans quiet by avoiding new inflammatory measures, hopeful that subsequent generations could discover a peaceful solution to the imperial dilemma.

North’s passivity worked for a time. However, in 1773 surging protests erupted once again, this time against a tax on tea, a parliamentary measure that antedated North’s ministry and had neither been enforced nor rescinded. When North’s government found reasons for implementing the legislation, three colonies — Pennsylvania, New York, and South Carolina — prevented ships carrying dutied tea from docking and unloading their cargoes. Protest leaders in Massachusetts, having failed to stop the vessels bound for their colony, staged the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, dumping today’s equivalent of several million dollars’ worth of tea into Boston Harbor. The extent of colonial defiance, and the wanton destruction of private property, brought the possibility of war to the forefront.

Such rage swept across England that further appeasement was out of the question. “[W]e must risk something,” Lord North avowed. His government contemplated an assortment of responses, including the use of force to crush the American rebels. Although the ministers foresaw little trouble in suppressing the insurrection, in 1774 they opted instead for peaceful coercion, something that had hardly been tried previously. Singling out Massachusetts for punishment, the ministry hit the colony with the Coercive Acts, measures that included a fine, closure of Boston Harbor until restitution for the tea was made, significant changes in the province’s 80-year-old charter, and an act that authorized sending arrested colonists outside the colony for trial.

The colonists learned the details of the acts in the spring of 1774. Although the legislation applied only to Massachusetts, it sparked outrage elsewhere. Many thought that London was pursuing a policy of divide and conquer. Today Massachusetts would taste repression; tomorrow it would be the turn of another colony. Though many outside Massachusetts disapproved of Boston’s destruction of the tea, a ubiquitous fear existed that if a faraway imperial government could alter the charter of one colony, it could transform the charters of all colonies. Such a step could radically change the structure of the provincial governments and even endanger cherished religious traditions.

Anger and apprehension were plentiful, but every American activist understood that to defy the Coercive Acts in all likelihood meant war. The point of no return had come. Parliament held inflexibly to the position that it could make any law that it wished for the colonies. American insurgents just as unwaveringly maintained that there were limits to Parliament’s power over the colonies, and some colonists insisted that Parliament had no power over the colonists. They recognized only the authority of the British Crown. It appeared to activists on both sides that the time had arrived when the alternatives were colonial submission or war.

Samuel Adams, Boston’s flinty, tireless, undaunted, and never-overawed popular leader, advocated that each colony embargo British imports until the Coercive Acts were repealed. However, a majority of provincial assemblies urged a conclave of all the colonies to determine a uniform American response. Such a body, they reasoned, was necessary to discover whether the will existed to implement a national embargo. Moreover, if defiance led to war, only a national assembly could determine if there was sufficient unity among 13 separate colonies to wage war with Great Britain. It was the prospect of hostilities more than any other factor that led the colonies to agree to meet in Philadelphia in September 1774 in what came to be called the First Continental Congress. It would determine how to respond to the Coercive Acts and answer the question of whether armed resistance was feasible. Some even saw a congress as the best hope of escaping war, thinking that a demonstration of colonial unity might cause London to back down again.

Every colony but Georgia sent delegates. The congressmen convened at a Philadelphia tavern on September 5, but quickly moved to Carpenter’s Hall, where they met several days a week for seven weeks. It was soon evident that the “Commencement of Hostilities is exceedingly dreaded here,” as John Adams, a delegate from Massachusetts, put it. Many congressmen were “fixed against Hostilities and Ruptures,” he said, unless they “become absolutely necessary, and this necessity they do not yet See.” War, those delegates believed, “might rage for twenty year, and End, in the Subduction of America, as likely as in her Liberation.”

Dread of war led to differences over how resolute Congress could afford to be. Some delegates, convinced that the colonies must continue to have “the Aid and Assistance and Protection of the Arms of our Mother Country,” held stubbornly to the belief that “we must come to Terms with G. Britain.” But a majority agreed with Congressman George Washington. He believed that the colonies should never under any circumstances “submit to the loss of those valuable rights & privileges which are essential to the happiness of every free State.” The divisions led the delegates “to steer” what John Adams called a “middle Course between Obedience and open Hostilities.”

Congress refused to create an army or acquire arms and munitions, though it encouraged the colonies to ready their militias for the possibility of war. It also agreed to an immediate national boycott of British imports and a year later, if necessary, a suspension of colonial exports within the British Empire. In a major concession by the hard-liners, Congress agreed that Parliament might regulate imperial commerce. Otherwise, Congress resolved that Parliament was powerless

Some delegates, convinced that Congress had laid the groundwork for war, were gloomily apprehensive as they left Philadelphia. Others, like Samuel Adams, were delighted by Congress’s determined stand. The delegates, he said, had manifested “the Spirit of Rome or Sparta.” Few, if any, thought the steps taken by Congress would bring an end to the imperial crisis, and a great many likely would have agreed with John Adams’s assessment: “We are ... at the Brink of a Civil War.” Every delegate knew that the decision for war or peace now rested with Great Britain, and in all probability most shared Washington’s outlook: If London pushed “matters to extremity,” more “blood will be spilt” than in all of America’s previous wars combined.

Once England learned in the summer of 1774 that an illegal American congress would meet, some officials foresaw the inevitability of war. That was how George III saw things. The “dye is now cast,” the monarch said, adding, “Blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent.” He also advised Lord North, who at times needed bolstering, that “we must not retreat.”

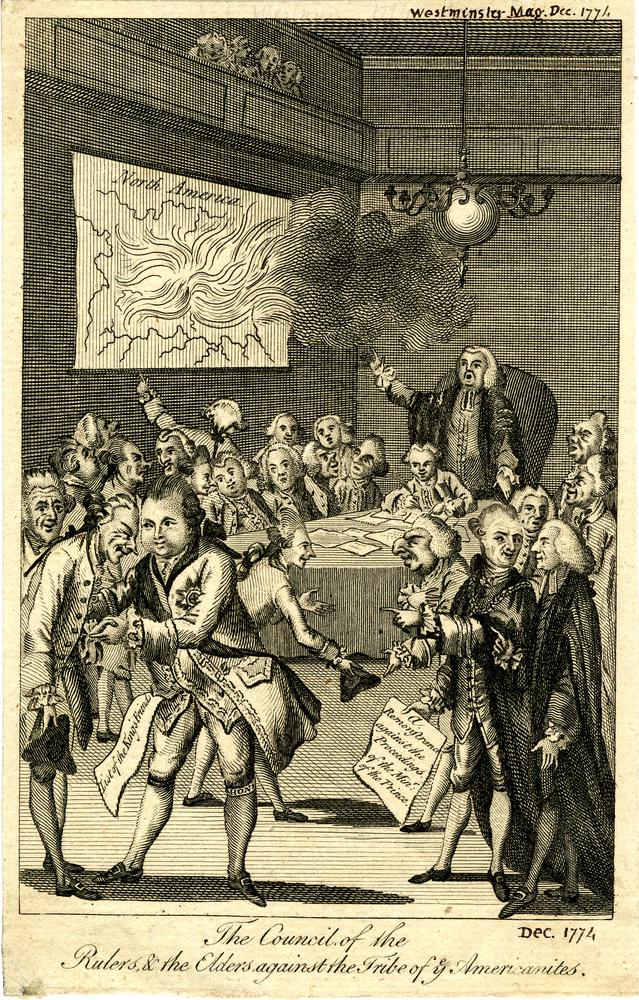

Official word from Congress itself at last reached London early in December 1774, but acting on the instructions of the king, who counseled that the decision of how to respond must be one of “reason not passion,” North’s ministry waited a month before beginning its deliberations. Throughout those 30 days most English newspapers truculently assailed the Continental Congress’s “defiant stand.”

The ministers took up the American question in January. Their discussions spun out for several days, but from the first it was clear that the overwhelming majority felt the time for negotiations and concessions had passed. The prevailing mood was to crush the insurgency by force. Few anticipated much trouble coping with the rebels, who possessed neither a national army nor a navy. Every colony had a militia system, but it was presumed that untrained and inexperienced militiamen could not put up much of a fight against Britain’s professional soldiers. Nearly all thought the war would be short. Some believed the colonists would capitulate the minute they understood that Britain was prepared to use force. Most anticipated a battle or two, but expected the colonists to lay down their arms once they tasted defeat. A lengthy war was not foreseen.

Even if the colonists somehow persisted after a couple of

The ministers clutched to the belief that most colonists remained loyal and that outside New England, and especially beyond Massachusetts, little sentiment existed for the rebellion. Some potentially troubling possibilities were raised. A lengthy conflict accompanied by heavy rates of attrition would cause acute distress, for heavy losses would necessitate finding more and more replacements, and that, in turn, could bring on social and economic troubles. However, virtually no one envisaged prolonged hostilities. Others wondered whether the army could successfully campaign in the backcountry, but most thought the capture of coastal cities would bring the colonists to heel. Of greater concern was the possibility that France and Spain might aid the colonists or enter the war against Britain, but most thought hostilities would be over before the Bourbons could act.

Throughout the crisis set in motion by the Coercive Acts, the ministry had received excellent advice from General Thomas Gage, who was both the royal governor of Massachusetts and commander of Britain’s army in America. Now in his mid-50s, Gage had soldiered for more than 30 years and had seen combat on numerous occasions. He had a solid education and when chosen to be a colonial chief executive in 1774 was looked on as honest, prudent, and discerning. Given his position as the army’s commander, a post he had held for the past decade, Gage was in the best position of any royal official in America to see the big picture. In a series of reports to London he warned that the rebellion was widespread, the colonists were preparing for war and might be capable of fielding a large and worthy military force, and backcountry residents would “attack any Troops who dare to oppose them.”

Gage also cautioned that New England’s soldiers would not be “rabble.” They would be “freeholders and farmers of the country,” and they would be “numerous.” As a consequence, he would need “a very respectable force” to cope with armed resistance.

In communiqués that reached London before Lord North’s government learned of the steps taken by the Continental Congress, Gage spoke often of the “violent party” and “hot leaders” in Massachusetts who were “spiriting up the people ... to resistance.” At the very moment that Massachusetts’s congressional delegates set off for Philadelphia, Gage wrote that “the popular fury” within the province

Despite his earlier admonitions, Gage, in the aftermath of Congress, still hoped against hope that war could be avoided. He advised that if London sent additional troops and arrested the “most obnoxious” rebel leaders, “the government will come off victorious,” possibly without having to use force. However, if the ministry chose war, it must send quite a large army to America. Britain’s army, in 1774, totaled 48,647 men, but Gage possessed a mere 3,400 troops in Boston. In October, he told London that if he could have 20,000 men, it would save Great Britain both “Blood and Treasure.” Gage also cautioned that the first engagement would be crucial. If the British force was too small to perform effectively, American defiance would stiffen. But if he possessed the numbers to utterly destroy the rebel army in the initial engagement, America’s will to continue fighting would crumble.

Toward the end of January 1775 the ministry made the momentous decision to use force. It voted to send Gage 3,000 additional troops, far fewer than he had warned would be needed, and with the knowledge that reinforcements could not possibly reach America before the first blow was struck. However much the ministers may have been influenced by Gage’s counsel, they clearly ignored his sage advice to defer hostilities until Britain’s army possessed the strength to overpower whatever military forces the insurgents could field.

Lord North then directed the American secretary, the Earl of Dartmouth, one of the few ministers who had opposed the decision for war, to draft the order to Gage to use force. Dartmouth’s communique of January 27 ordered “a vigorous Exertion of ... Force.” Gage was not to shrink from sending men into the backcountry and he was to arrest the “principal actors & abettors” of the rebellion in Massachusetts.

Summarizing what his fellow ministers had been saying in coming to this decision, Dartmouth told his commanding general that any resistance offered by the rebels “cannot be very formidable,” as they were “a rude Rabble without a plan, without concert.” Hostilities should end with “a single Action,” he predicted. Even so, Dartmouth added that a cavalry regiment, three infantry regiments, and 700 marines were being sent.” Less than a month later, Dartmouth notified Gage that “should it become necessary,” four regiments from Ireland, an additional 1,700 men, could be sent.

Near the time that Dartmouth’s order to use force

A month after Lord Dartmouth’s order was sent, Lord North finally addressed Parliament. Already the Earl of Chatham, William Pitt, an iconic figure in England given his heroic leadership in guiding Britain to victory in the Seven Years’ War, had spoken against war. A week before Dartmouth drafted his message to General Gage, Chatham, old and infirm, afflicted with rheumatism, gout, depression, and probably cardiac issues, appeared before the House of Lords and spoke while leaning on a cane for support. Chatham gallantly urged Parliament to acknowledge the right of the colonists to legislate for themselves in internal matters and to embrace the American Congress’s willingness to accept London’s regulation of imperial trade. He urged his colleagues to choose “concord, peace, and happiness,” and by all means to avoid hostilities. To go to war would be to embark on a fool’s errand, he said, adding that Britain could not win the war. The army could seize towns and colonies, but it would never have the numbers to control “the country it left behind” as it tramped from province to province.

Pitt warned that America was 1,800 miles long and filled with “valorous” citizens who cherished liberty and could never be brought to heel. France and Spain, he added, were watching and “waiting for the maturity of your errors” before they pounced. “Let us retract when we can, not when we must,” beginning with the immediate recall of Britain’s army.

North went before Parliament on February 20 to speak at length about the American crisis, but he divulged neither that his government had decided on war nor that the order to use force had gone out. Even so, it was generally presumed that the ministry was committed to war. Weeks before North spoke, Edmund Burke, a young Irishman who a year earlier had made the principal speech in the Commons in opposition to the Coercive Acts, correctly advised correspondents in New York that the government would “embrace no conciliatory measures.” The king had already opened the session in January by urging a “firm” response to American defiance, a stance that members of North’s faction in Parliament parroted. Some even insisted that taking a hard line did not mean war. It was “romantic to think the colonists would fight,” they maintained, given that American men were “cowardly.”

North spoke frequently that winter, but his initial speech set the tone. If the colonists refused to accept the sovereignty of Parliament, he promised, “we can meet no compromise.” He burnished his tough talk with a feigned “peace plan.” He told the king in

One of his admirers proclaimed that the prime minister’s statesmanship would “render Ld. North’s name immortal in our English history.” However, fearing that increased taxation at home would foster opposition to the coming hostilities, North had already reduced the navy. In 1775, he turned a deaf ear to the entreaties of the Earl of Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty, who urged wartime mobilization of the Royal Navy. Expansion of the navy would not begin until October 1776 and comprehensive mobilization was not launched until January 1778.

North’s actions brought on the final prewar parliamentary debate on the American crisis, and once again it was Burke who made perhaps the most important speech against going to war. He had moved from Ireland to England years earlier to study law, but politics became his calling and by 1775 he had sat in the Commons for 10 years. Portly, with dark wavy hair, and habitually in debt from living above his means, Burke had long since become a luminary among the foes of Britain’s American policies. Echoing Chatham, Burke in March told the Commons that it was madness to pursue “peace through the medium of war.” Peace must be “sought in the spirit of peace.” If force was used, there was “no further hope of reconciliation” and Britain would lose America, where the “fierce spirit of liberty is stronger .. than in any other people of the earth.” He hinted at refashioning the British Empire along the lines of a commonwealth system in which the nearly autonomous colonists were bound by loyalty to the king. It was a radiant and rational address, and it largely fell on deaf ears.

General Gage, in Boston, had been busily preparing for war since he’d learned that an American congress was to meet. The arrival of a smidgen of reinforcements, as well as units that he’d redeployed from Halifax, Philadelphia, and New York, had brought his troop strength up to roughly 6,000 men by the spring. Aware that many of his men were young and inexperienced—one-third had served for less than three years and next to none had ever experienced combat, prompting one senior officer to moan that this was an “army of children”—Gage stepped up training exercises. He had his men

When one such mission to Salem in February came within a whisker of provoking armed resistance, Gage confessed that the undertaking had been a “mistake.” Thereafter, he abandoned these initiatives. He desperately wished to avoid responsibility for triggering hostilities. It would be better if the decision to fire the first shot was made in London and even better if the American rebels were the first to open fire. Gage’s long wait for a war that he suspected was inevitable ended on April 14 when HMS Nautilus arrived bearing Dartmouth’s order to vigorously exert force. Gage had earlier prepared a plan for this eventuality, a strike against a rebel arms depot in Concord, about 20 miles west of Boston. He chose that target because its proximity to the city meant the operation could be concluded rapidly before many Massachusetts militiamen responded, but also because he wanted to get his hands on two insurgent ringleaders, Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were known to be in Lexington, which lay astride the road to Concord.

Military plans are notorious for going awry, and Gage’s went off the rails. He knew that surprising the colonists was essential to the success of the undertaking, but the insurgent’s spy network in Boston had learned of his plan. Before the British soldiers moved out, dispatch riders, including Paul Revere, galloped into the hinterland to warn as many village militia units as possible that the regulars were about to march on Concord. Gage also contributed to the looming disaster by sending too few men. He chose companies of grenadiers and light infantry, the cream of his army, but fewer than 900 men were dispatched, barely 15 percent of the troops in Boston.

The march was uneventful until the troops reached Lexington. Upon entering the hamlet, they discovered that the local militia company awaited them. Heavily outnumbered, the militiamen offered no resistance, but when ordered to disperse, a shot rang out. No one knew who fired that shot or whether it was accidental or deliberate. But in the tension-packed atmosphere on Lexington Green, that gunshot precipitated a burst of shooting that spilled blood on both sides. No British

Seven militiamen were killed, two in the first volley and five others before British officers reestablished control of their frenzied troops.