Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Matthew Spalding is Dean of the Van Andel Graduate School of Government at Hillsdale College’s Washington, D.C., campus, and the author of several books including We Still Hold These Truths: Rediscovering Our Principles, Reclaiming Our Future, in which portions of this essay appeared. His most recent book is The Making of the American Mind: The Story of our Declaration of Independence.

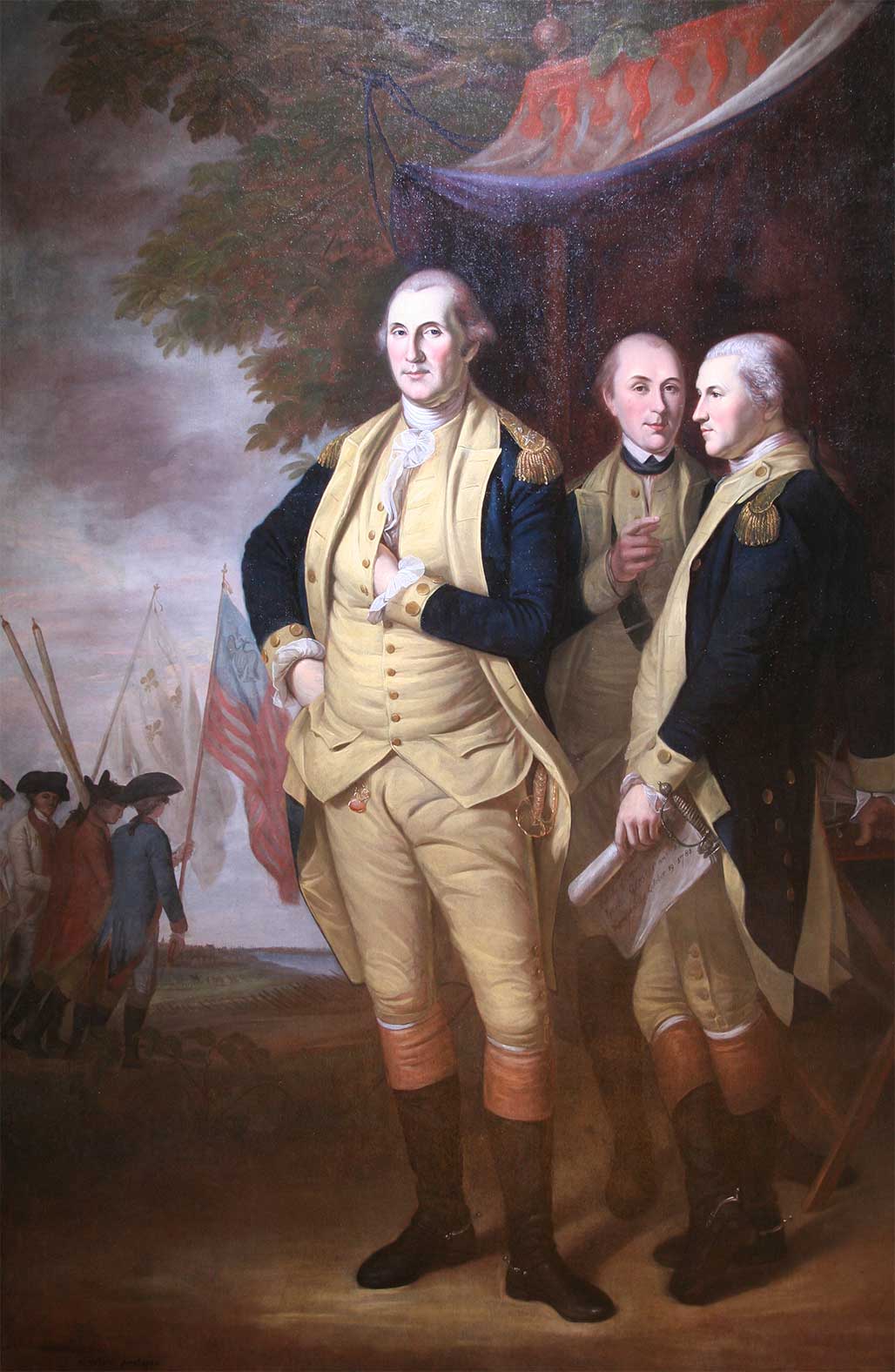

In 1783, after the Battle of Yorktown had been won but before the treaty of peace was concluded, General George Washington sent his last report as commander of the Continental Army to the state governors. In his final Circular Address, as it was called, Washington observed that Americans were now free and in possession of a great continent rich in “all the necessities and conveniences of life.” The potential of the new nation was virtually unlimited, given the times and circumstances of its birth. Washington captured the significance of the moment in powerful language:

One can hardly imagine a better beginning. “At this auspicious period, the United States came into existence as a Nation.” Under such circumstances, it would be hard not to be optimistic about the future. But then, as when a symphony abruptly shifts to the strains of a minor key, Washington struck a jarring note: “and if their Citizens should not be completely free and happy, the fault will be entirely their own.”

With the war won, the hard work of constructing a nation was upon them. It would be up to the American people, Washington warned, to decide for themselves whether they were to be “respectable and prosperous, or contemptable [sic] and miserable as a Nation.”

What they did now would determine whether the revolution would be seen as a blessing or