Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities and Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University. He is the author of several award-winning books on Lincoln, including his most recent, Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment, from which portions of this essay were taken.

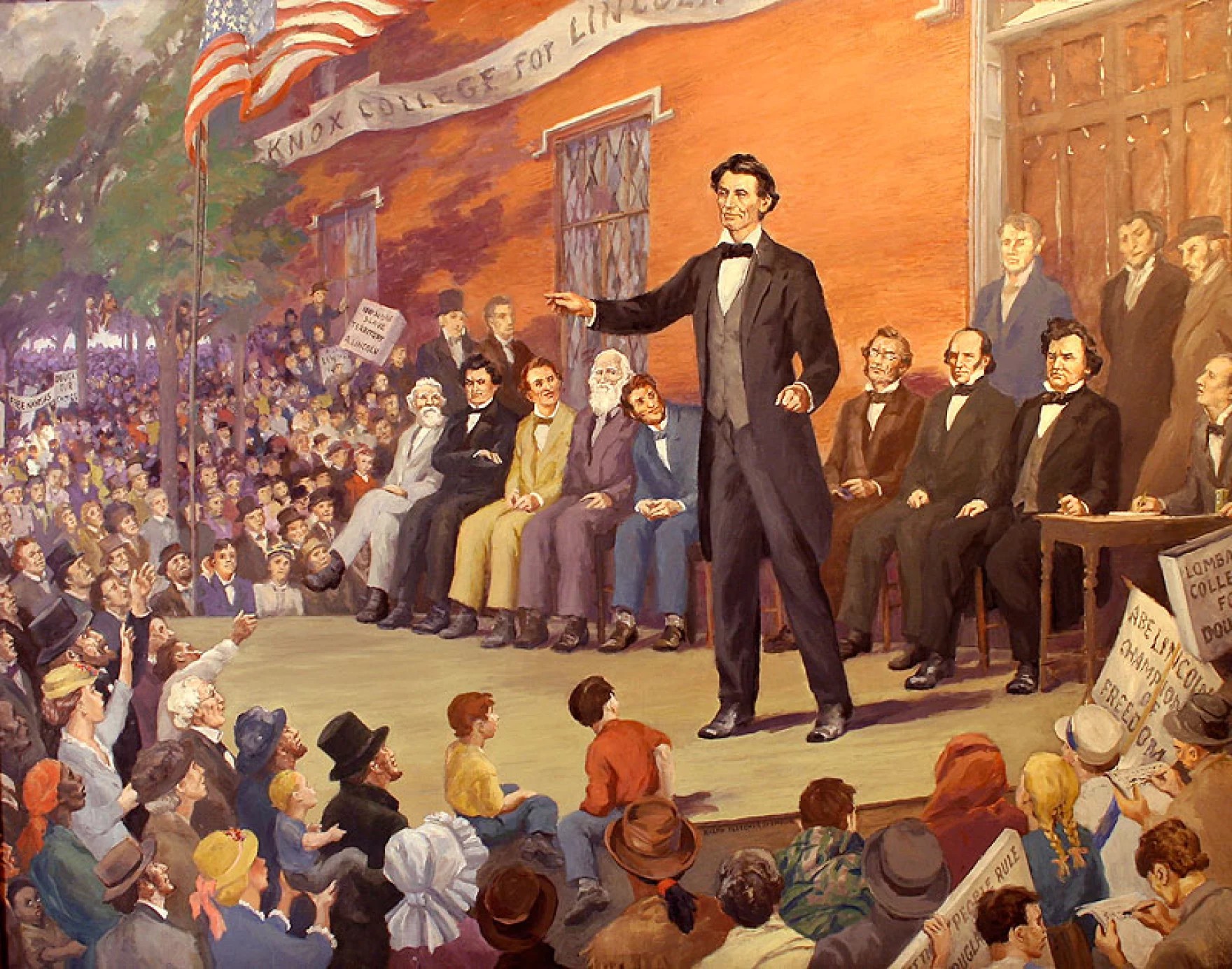

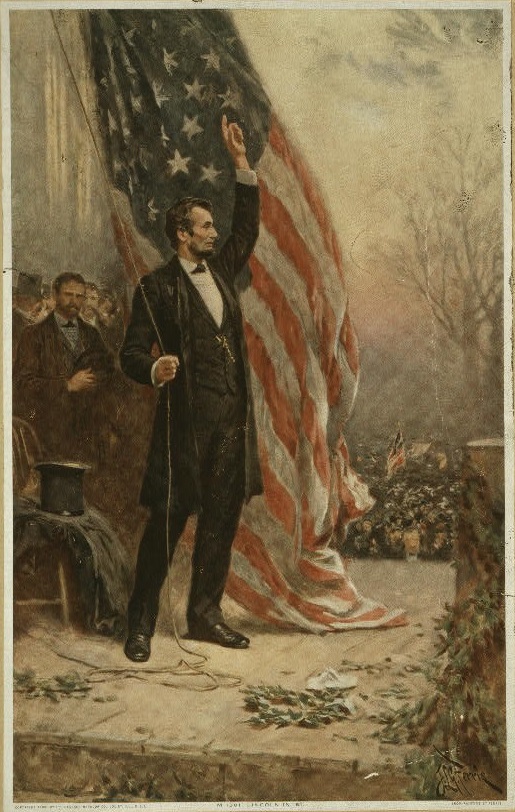

The word “democracy” occurs only 137 times in the collected writings of Abraham Lincoln. But no other word described what he saw as the most natural, the most just, and the most enlightened form of human government. Nothing, he said, could be “as clearly true as the truth of democracy.” And nothing demonstrated that truth more clearly in Lincoln’s mind than the American democracy, which embodied “the great living principle of all Democratic representative government.’”

Lincoln’s confidence in democracy was based on three evidences, beginning in the plainest terms with what it had done for him. His own experience illustrated how the absence of a permanent hierarchy in American life permitted anyone to transform themselves. “The principle of ‘Liberty to all’” was “the principle that clears the path for all – gives hope to all – and, by consequence, enterprize, and industry to all.”

As soon as he had entered into adulthood, Lincoln was intent on taking that path and “cutting entirely adrift from the old life” he had known on his father’s farm. He was “not ashamed to confess” in 1860 “that twenty-five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat boat – just what might happen to any poor man’s son.” Not ashamed, because in America, there were no artificial restraints of class, birth, or hierarchy: “every man can make himself.”

Lincoln had been “a strange, friendless, uneducated, penniless boy,” but in the democratic air of America, “the prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him.”

He could even aspire to the highest office of that democracy. “I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House,” he told an Ohio regiment that he reviewed outside the Executive Mansion in August 1864. “I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father’s child has. It is in order that each of you may have through this free government which we have enjoyed, an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence; that you may all have equal privileges in the race of life, with