Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Sven Beckert is a professor of history at Harvard University and winner of the Bancroft Prize for his previous book, Empire of Cotton: A Global History. His recently published book, Capitalism: A Global History, is a comprehensive history of capitalism in a wide geographical and historical framework, tracing its history during the past millennium and across the world. Beckert’s research draws on archives in six continents. Portions of this essay appear in that book.

In 2016, a writer at Salon made a radical argument: Capitalism had reached a point at which “its complete penetration into every realm of being” had become a distinct possibility. No imperial or totalitarian project has ever come close to capitalism’s success at nestling into the nooks and crannies of human life. No religion, no ideology, no philosophy, has ever been as all-encompassing as the economic logic of capitalism.

In the twenty-first century, that energy continues to propel economic life. There are the almost quaint frontiers of the old-fashioned kind with commodities such as sugar, soy, tea, coffee, and oil palm. At the cutting edge are deep-sea mining and mining on celestial bodies, bringing private property rights into the world’s oceans and outer space.

Commodification – the turning of things into products that can be bought and sold on markets – pushes into yet more surprising spaces as well. Sports, for example, has been radically commodified, with soccer becoming a multibillion-euro industry where everything is for sale – players, images, clubs. Our very attention has become a commodity, too, with social media companies working to lure and hook our preferences in order to sell them.

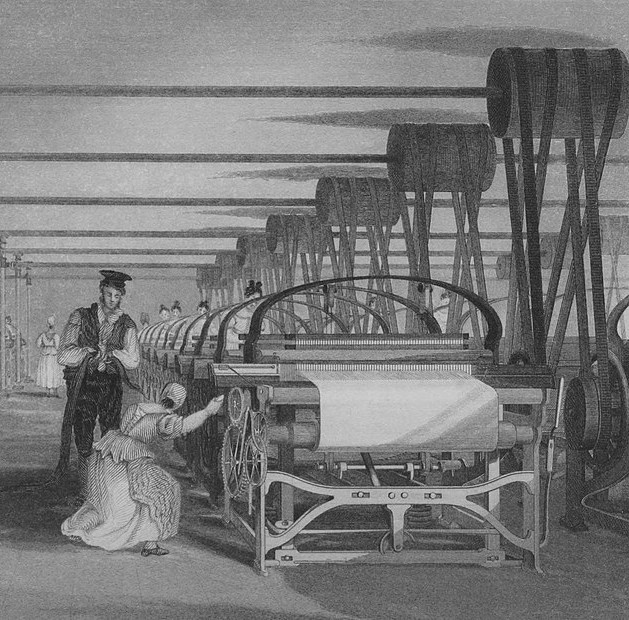

In many ways this process began in late eighteenth-century Britain when something radically new emerged: Capital owners began to locate production in factories, employing wageworkers to operate sophisticated machinery, first powered by water, later by steam. In these places, industrialists gained an entirely novel degree of control over manufacturing, one akin to what they had realized earlier on plantations. The capitalist revolution shifted its cutting edge from commerce and agriculture to industry, thus sparking the Industrial Revolution.

Before, capitalism had been a “vast but weak” system as Fernand Braudel has described it. Proto-industrialization had spread around the world, and in scattered places became full-blown industrialization by harnessing the revolutionary energy of capital to the endless possibilities of technology. Industrial capital gained tremendous strength in what historians have called the Great Divergence: the moment at which a small part of humanity concentrated in Europe became much wealthier than anyone else.