Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

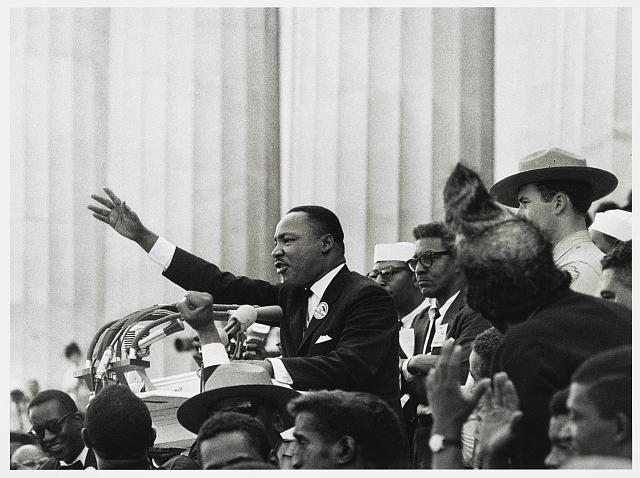

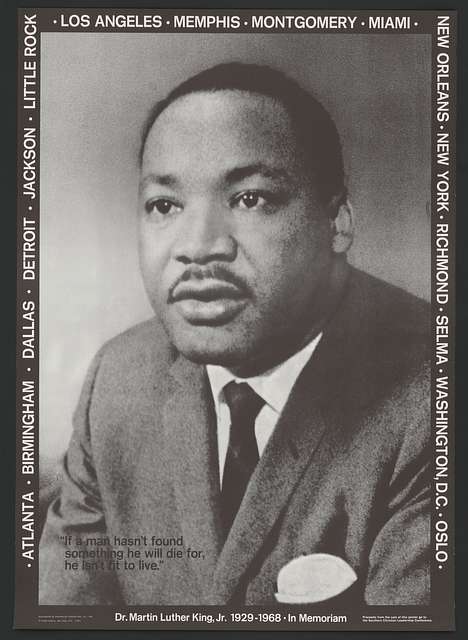

This month we celebrate another birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the civil rights hero who was gunned down in Memphis in April 1968 at the age of 39. Since King’s death, historians and others across the political spectrum have hotly contested the meaning of his legacy. Who’s right?

Over the years, many conservatives have vocally laid claim to King’s intellectual and political bequest. William Bradford Reynolds, who served as Ronald Reagan’s assistant attorney general for civil rights, and who waged a long battle against affirmative action, claimed that “the initial affirmative action message of racial unification — so eloquently delivered by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. . . . was effectively drowned out by the all too persistent drumbeat of racial polarization that accompanied the affirmative action preferences of the 1970s into 1980s.” Ward Connerly, the conservative black businessman who spearheaded California’s Proposition 209, barring affirmative action, announced that his group was “going to fight to get the nation back on the journey that Dr. King laid out.”

In their effort to lay claim to King, much as generations of politicians strove to “get right with Lincoln,” conservatives have presented an ahistorical portrait of him as an absolutist on the question of race and public policy. By their estimation, King’s “I have a dream” speech should be taken literally: He espoused a civic order where governments made no distinctions between citizens based on race. Hence he would have opposed compensatory set-asides, quotas, or timelines and targets aimed at redistributing jobs and economic resources.

The problem with this version of history is that it ignores much of what King said. In his book Why We Can’t Wait, he wrote that “no amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America down through the centuries. Not all the wealth of this affluent society could meet the bill. Yet a price can be placed on unpaid wages. The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of the labor of one human being by another. . . . The payment should be in the form of a massive program by the government of special, compensatory measures which could be regarded as a settlement in accordance with the accepted practice of common law. . . . I am proposing, therefore, that, just as we granted a GI Bill of Rights to war veterans, America launch a broad-based and gigantic Bill of Rights