Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Edward J. Larson is s professor at Pepperdine University and the University of Georgia, where he has taught for twenty years. His many books include Summer for the Gods, winner of the 1998 Pulitzer Prize in History, and most recently Declaring Independence: Why 1776 Matters, in which portions of this essay appeared.

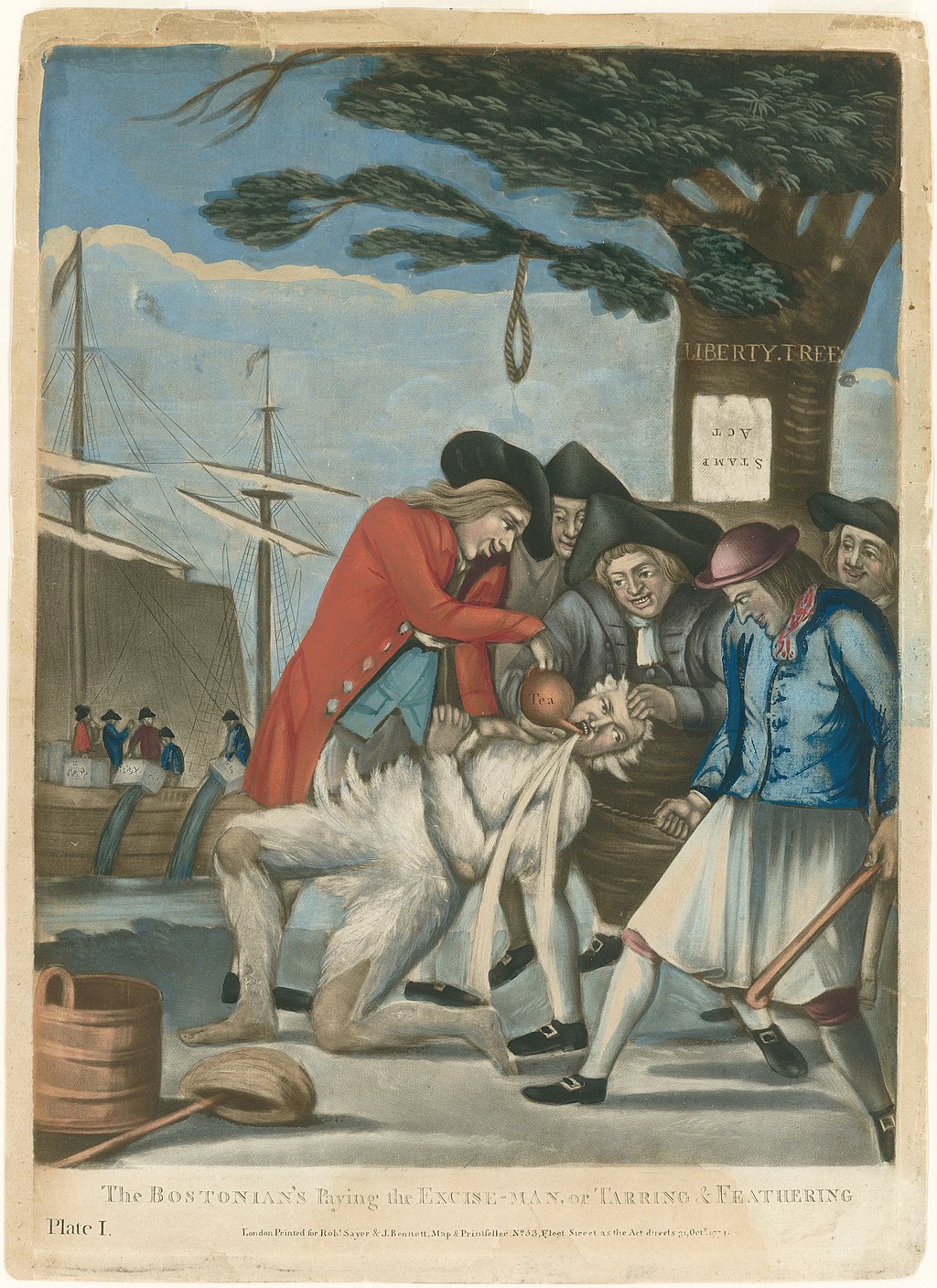

America’s year of independence, 1776, began with virtually all those living in Britain’s thirteen North American colonies content to remain under royal rule so long as they could enjoy the basic rights of British subjects. By year’s end, most Americans who had a position on the matter favored separation from Britain. Although it was a year of intense fighting, much that mattered in 1776 happened away from the front lines of combat. Deeds on the battlefield were punctuation for inspiring words of liberty written and spoken throughout the colonies. The full history of 1776 sheds light on what mattered to Americans then and the legacy it left thereafter.

The year did not see a fundamental change in the contours of the fight for freedom. The storied battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill occurred during the spring of 1775. In June 1775, the Second Continental Congress named George Washington to lead a newly formed American army composed of colonial militias that were besieging British forces in Boston, and it adopted the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms a month later. Even the American conception of liberty did not change in 1776.

The individual rights declared in the state constitutions of 1776 echoed the Anglo-American rights demanded of Parliament in earlier petitions by the colonies and Congress. Slavery did not end in any state during 1776. Native Americans gained no legal rights, a woman’s status remained much the same, voting continued to be mainly the prerogative of property-owning males, and no state addressed economic inequalities.

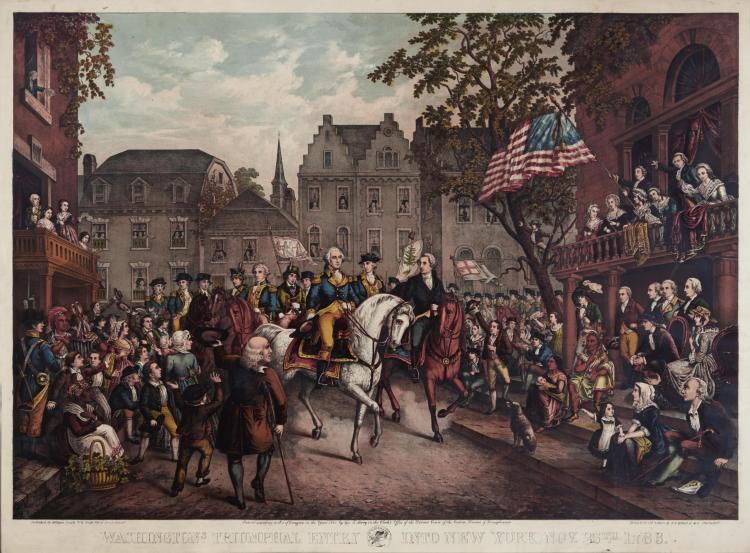

On the military front during 1776, the Americans drove the British from Boston and kept them out of Charleston, South Carolina, but lost New York City, Newport, and Canada. On balance, despite a small but inspiring year-end victory at Trenton, the Americans ended the 1776 military campaign in a weaker position than they began it. Defeat in the Battles of Long Island and Fort Washington left thou-sands of American prisoners of war in British prison hulks, and the remains of Washington’s army huddled in Morristown, New Jersey, while the British Army settled into winter quarters in New York City.

The fighting that occurred during 1776 mattered at the time mainly because it kept the Americans in the war, but battles fought at Saratoga and Yorktown in 1777 and 1781 brought American victory. What changed in 1776 was Americans’ embrace of