Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

In the opening months of the Revolutionary War, America’s ragtag militias and jerry-built Continental Army squared off against the most professional army then on the planet. The battles of Lexington and Concord demonstrated that Americans would fight, and fight hard.

Two months later, they won respect at Boston’s battle of Bunker Hill, yielding the battlefield but inflicting punishing casualties that staggered British officers. Thirteen thousand New Englanders raced to surround Boston and seal off the enemy forces from the rest of North America. The Royal Navy would be forced to evacuate those troops.

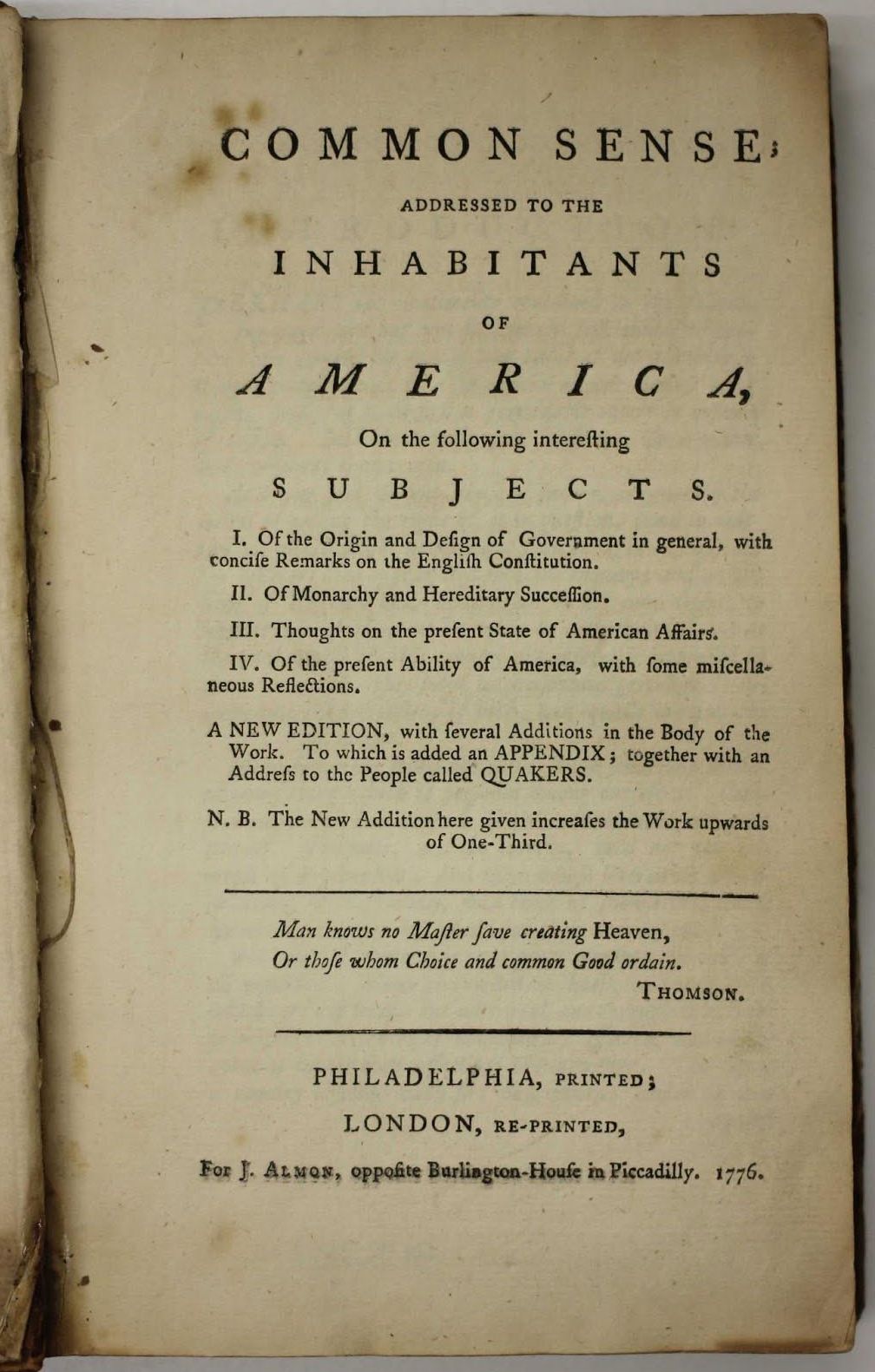

But British power soon took its toll. A multi-pronged American invasion of Canada ended ignominiously. Some Americans wavered, uncertain whether their goal should be independence, or simply winning greater respect from British officialdom, or peace at any price. At the end of the year, a pamphlet by a recent immigrant from England brought focus to that choice, persuading great swaths of colonials that only independence would do.

In 1775, few thought thirty-eight-year-old Thomas Paine was on the cusp of great achievement. The son of an Anglican mother and a Quaker father, he knew only a few years of schooling. His first wife died in childbirth. A second, childless marriage dissolved. He sailed for a few months on a privateer in the English Channel, occasionally taught school, and unsuccessfully took up his father’s trade as a maker of stays for ladies’ corsets, instruments of quiet torture designed to shape female bodies to hourglass proportions.

Paine became one of the King’s tax collectors, an occupation often despised on both sides of the Atlantic.. Twice discharged from the tax service – once for unexplained absences, once for apparent irregularities – he petitioned the British government for improved pay and conditions for collectors. His petitions didn’t succeed, though he fell in with English radicals who questioned the Royal government.

When Paine sought out Benjamin Franklin in London in 1774, the American sage suggested crossing the Atlantic to America. The former collector soon would become the voice of America’s founding tax rebellion.

In the New World, Paine found work as a writer and editor in Pennsylvania. Sensing that America’s revolutionary ardor might wane, Paine recognized that the rebellious colonies faced a momentous choice. Did they simply want lower taxes? Or perhaps to win a colonial legislative body that would be subordinate to Parliament in London, while remaining within the British Empire? Or should they aim higher? The unknown scribbler chose the most audacious goal, rallying American spirits by explaining that they must oppose monarchy and repression.

In the most popular version of Common Sense, Paine opened with a soaring