Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1959, Summer 2025 | Volume 10, Issue 5

Authors: John Dos Passos

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1959, Summer 2025 | Volume 10, Issue 5

Editor's Note: Architecture was not the least of Thomas Jefferson’s formidable talents. In his designs there was much of the monumental dignity of the classical models which all his life he sought to emulate. Could not America revive the glory that was Greece and Rome? In the early years of the Republic, his aspirations—and those of the men he so profoundly influenced—were focused increasingly on the sprawling tract of Maryland farm country where a national capital would one day rise. How these aspirations took shape is told in the following chapter from John Dos Passos’ book, Prospects of a Golden Age, to be published in October by Prentice-Hall.

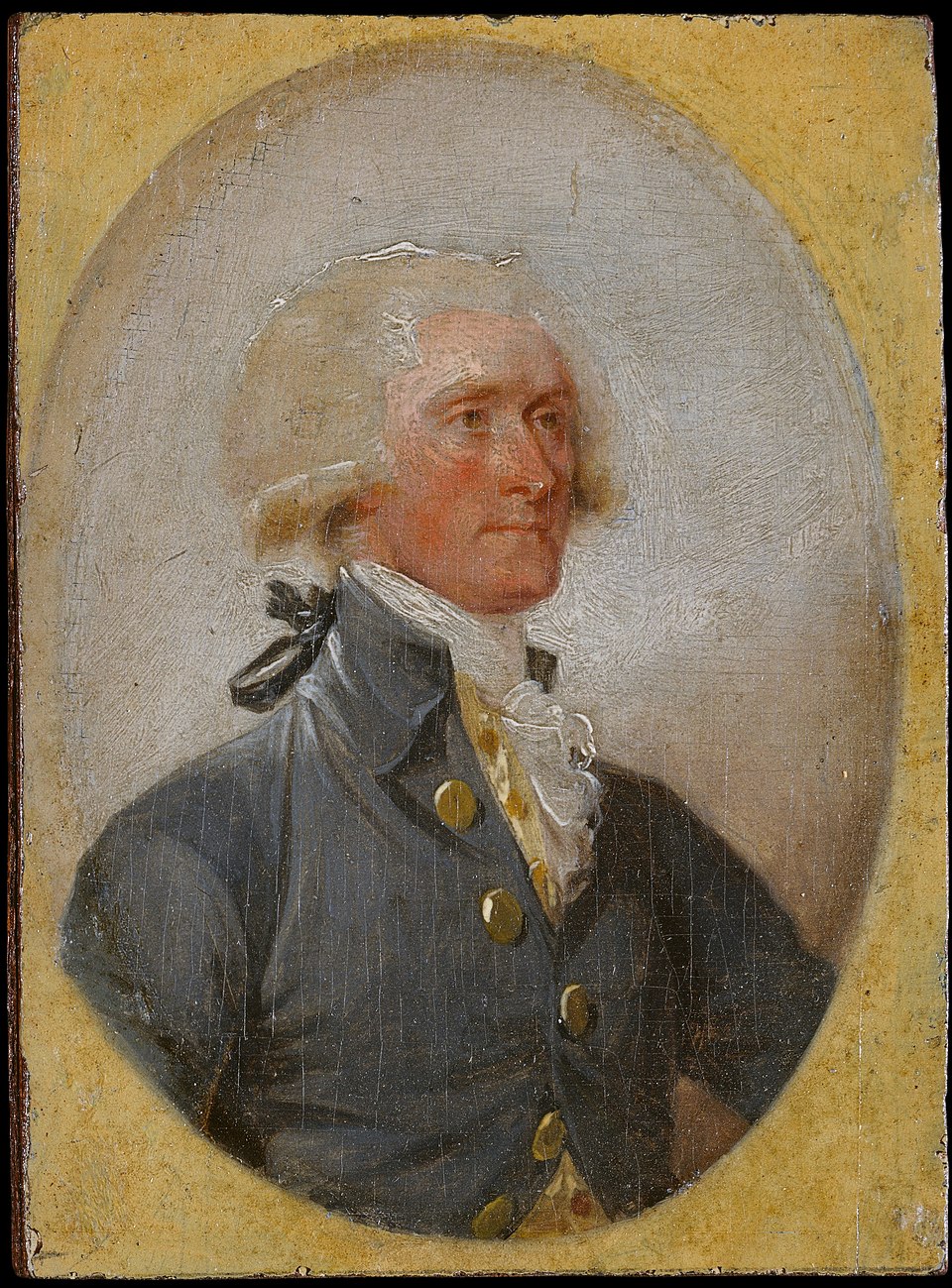

Thomas Jefferson used to say that he considered architecture the most important of the arts “because it showed so much.” Jefferson was responsible, more than any other single man, for the introduction into America of the Greek Revival style. As the state-builders searched the histories of the Greek and Roman republics for models for their institutions, the architects studied the classical forms so lately rediscovered by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and his school of Roman archaeologists. They wanted to put up dwelling houses and public buildings that would express the ambitions for human dignity and social order which so many of them felt. For them the style of the Greek Revival stood for those “prospects of a golden age” on which they had set their hopes for mankind.

Jefferson became one of the leading architects of his day. His influence did a great deal to form the architectural ideas of men like William Thornton and Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Robert Mills. In all his designs, from his forgotten work at Williamsburg to the final establishment of a distinctive style in the University of Virginia, he sought always proportions that would enhance the human figure.

His mind was already full of plans for building when, in 1766, during the summer of the repeal of the Stamp Act, he took time off from his law studies with George Wythe in Williamsburg to drive to Philadelphia in a two-wheel chair. The pretext was to get himself inoculated against smallpox. An eager, curious young man, he wanted to see the world. In his pocket he carried a letter from his friend Dr. George Gilmer to Dr. John Morgan, a Philadelphia physician freshly arrived from Europe.

Dr. Morgan was just the man Jefferson needed to put him in touch with everything and everybody. The young physician, already among Philadelphia’s bestknown, had traveled to England armed with that indispensable letter from Dr. Franklin. After some

“Laureated” by the town fathers of Edinburgh, Dr. Morgan crossed to the Continent for the grand tour. In Rome he visited the museums and antiquities and made careful notes, which survive with a fragment of his journal to this day. He met the painter Angelica Kauffmann, and all the cognoscenti of Winckelmann’s group. Dr. Morgan treated “Miss Angel” for some ailment, and in return she not only presented him with her portrait but painted his.

As full of enthusiasm for painting and architecture as for medicine, he collected paintings as he traveled, bought copies of Titians and Veroneses and drawings attributed to the great masters, and jotted down what he was told about the architectural proportions of the colonnades and the rules of fenestration. On his way north from Padua he went to Vicenza, visited palaces built by the great Renaissance architect, Andrea Palladio, marveled at his triumphal arch and at his magnificent reproduction in wood of a Roman theater. He procured, so he noted, “a pretty exact plate” of Palladio’s theater.

Dr. Morgan arrived home bursting with the beauty of classical ruins. He settled in a fine house and unpacked his collection of paintings and, what must have been particularly interesting to Jefferson, his architectural drawings, which included a temple façade by Mansart and a plan of a country house.

As he visited Dr. Morgan’s collections, undoubtedly Jefferson’s soul was struck and his ideas expanded by this glimpse into the European world of fashion and science and elegance and evolving thought. Morgan’s talk of the marvels of the antique background must have stirred up all Jefferson’s longings to travel abroad. With the family at his Albemarle County birthplace, Shadwell, dependent on his management of the estates now that his father was dead, and his way to make as a lawyer, that was now out of the question. The notion may have started sprouting in his mind that here in America, on the shaggy hills of his own Virginia, a civilization could be built, new, separate, and superior. This was the aim to which, more explicitly than any other man of his generation, he was to dedicate his life.

A civilization meant a setting. Man’s setting was architecture. Jefferson was already familiar with some of the builders’ manuals so much in use at the time. As early as the summer of 1763 his thoughts had turned to building himself a house of his own in WiIliamsburg. “No castle, though, I assure you,” he

Not long after Jefferson returned home from his trip up the coast, he started to build himself a house. He was already steeped in Palladio when he designed the first version of Monticello. It was typical of his radical and personal approach to everything he handled that he immediately worked his way through the superficially fashionable elements of English Palladianism and came to grips with the basic problem.

He wanted a manor house that would afford airy rooms and plenty of windows through which to look out on the big Virginia hills and the blue plain that moved him as much as music. He wanted a manor house which would combine under one roof the barns, storehouses, harness rooms, butteries, pantries, kitchens, tool sheds, stables, and carriage houses that were essential to the functioning of a plantation.

Palladio’s villas were a combination of dwelling house and barn.

When the style was adapted for the British noblemen (of whom Jefferson’s schoolmaster James Maury had written that their vast annual revenue ranked them with, “nay set them above many, who, in other countries, claim the royal Style and Title”), the practical features that attracted the frugal Italians were forgotten. Jefferson’s design for Monticello went back to PaIladio’s practical villa, which was essentially a farmhouse flanked by sheds; and by skillful use of his hilltop managed to go Palladio one better by establishing the working part of the building in the wings built into the hill and lighted by loggias—roofed open galleries—which could be used to shelter his equipment. Their roof he used as a terrace from which to enjoy his unobstructed view.

See also: "Monticello," by Robert A.M. Stern in the Fall 2017 issue

Thus Monticello embodied in its structure the basic plan of his life, and of the lives he wanted for his friends and neighbors: a combination of practical American management of plantations large or small with the freedom enjoyed by the British noble, which warranted (to quote again from Maury’s letter)

Jefferson threw into the building of Monticello all his capacity for original planning and for meticulously detailed work. Whether or not he had already designed the porches at Shirley and the Randolph-Semple house at Williamsburg, as Thomas Waterman suggests in his Mansions of Virginia, by the time he tackled the plan for the first version of Monticello late in the 1760’s, he was enough of an architect to make innovations in his own right.

The war, public service, his beloved wife’s death, the difficulties of a widower trying to raise a brood of small girls—everything took Jefferson’s mind off architecture during the stormy decade that followed. It wasn’t until 1785, when he was established in Paris as American minister, that he found the leisure to study the art that “showed so much.”

Outside of the diplomatic grind, he had been entrusted with two commissions that gave him real pleasure to execute. One was to find a sculptor worthy of carving a statue of Washington, and the other was to furnish Virginia with plans for a new capitol.

For the sculptor he immediately picked Jean Antoine Houdon, whose seated figure of Voltaire was already famous. Houdon at 44 was undoubtedly the best sculptor in Europe. He had won the grand prize at the Beaux Arts at eighteen and hurried off to Rome and Winckelmann. After ten years of studying fragments of Roman copies of Greek fragments, through which artists were beginning to re-imagine the cool purity of the Attic style, Houdon carved a Diana so thinly draped that she caused great scandal when she was exhibited at a salon in the Louvre. Catherine of Russia, who was the patron of the avant-garde arts of the time, carried the naked lady off to St. Petersburg. As a result Houdon found himself with orders from all the “enlightened” European courts.

When Jefferson went to see him, he consented to leave the statues of kings unfinished and to make the hazardous voyage to America to do a head of the greatest man of the age. They agreed it was absurd to try to work from a portrait when the original was at hand at Mount Vernon.

A certain amount of republicanism already went along with a taste for the Hellenic. Attracted by George Washington’s glory, Houdon agreed to do a bust for considerably less than he charged royalty, but insisted that his life must be insured at ten thousand livres for the benefit of his family in case

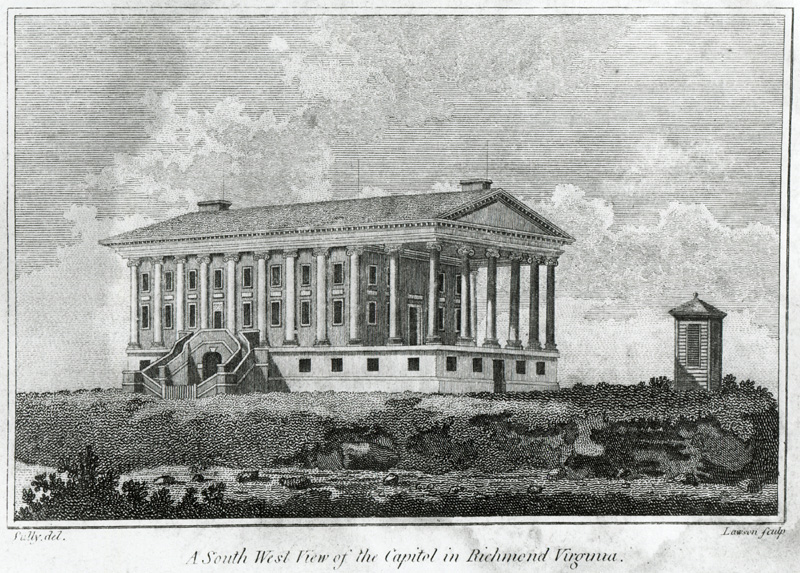

In the execution of his second commission, a capitol for Virginia, Jefferson found himself embarked on the full current of the same classical revival that had helped clear Houdon’s style of baroque angularities during the years he studied in Rome. Ever since Jefferson had drawn up the first bill for the removal of the Virginia capital from Williamsburg to Richmond he had been exercised about what sort of buildings would be constructed there. He had slipped into his bill the clause which he hoped he could turn into something new and fine: “said houses shall be built in a handsome manner with walls of Brick or stone, and Porticos, where the same may be convenient or ornamental.”

At some early date he had already been experimenting with a tentative sketch of a plan to transform the governor’s palace in Williamsburg into a temple-form building with columns in front and back. From the moment he first opened a copy of Leoni’s Palladio he must have been taken with Palladio’s drawings and measurements of the “Maison Quarrée” (he always followed Palladio’s spelling of Carrée) at Nîmes.

As Jefferson pondered an architecture that would express the essence of the young republic, his mind settled more and more on the Maison Carrée. Now in Paris he discovered a man who had recently published a set of drawings of the Augustan temple even more carefully measured than Palladio’s had been.

Charles-Louis Clérisseau was dean of the academy of painting and sculpture which had its seat in a set of apartments in the Louvre. He had returned from Rome after years of study. Under Winckelmann’s influence he had measured the ruins at Nîmes, and crossed the Adriatic to Spalato on the Dalmatian coast to sketch Diocletian’s gigantic palace there.

The capitol at Richmond was to plant this classical revival in the New World. Both in England and America, and in Russia too, the style in its various forms stemmed directly from Clérisseau’s album of archaeological drawings.

When Jefferson went around to Clérisseau’s studio, soon after arriving in Paris, the elegance and balanced strength of the Greek temple form burst on him anew. Immediately

At Clérisseau’s for the first time, Jefferson found himself with the resources of a proper architect’s drafting room. Modelers and draftsmen were ready to put his amateur’s improvised sketches into a form usable by a contractor. He learned to work with a hard pencil. Henceforth his architectural drawings had a professional air. He bought enough co-ordinated paper in Paris to last him most of his life. In Clérisseau’s portfolios he could thumb through pictures of about what had been so far unearthed of the Greek and Roman heritage. He kept coming back to the Maison Carrée.

He was choosing Roman architecture at the moment when it was nearest to Greek. “We took for our model,” he wrote Madison of Montpelier,

“Would have,” he wrote, in the past tense, because he had received the news that the contractors appointed by the Assembly were already laying the foundations for a capitol, and was afraid that they would go ahead with the building without waiting for his plans, which Clérisseau’s draftsmen were at that moment drawing up.

Clérisseau seems to have been surprised and delighted to find in this tall, angular envoy from the Virginia mountains un vrai amateur de l’antiquité . He furnished the archaeological information, but the plan was essentially Jefferson’s. For simplicity, or perhaps because he despaired of getting Corinthian capitals properly executed in America, he changed the order of the porch to Ionic and thereby helped give the whole school of architecture that was to follow in the United States its distinctively Ionic flavor. He designed the interior chambers for the House and Senate and the conference room between, which the constitution called for. The arrangement of the windows was Jefferson’s, and it was he who insisted against the Frenchman’s advice on following exactly the proportions indicated by Clérisseau’s own measurements of the actual temple at Nîmes.

It is likely that Clérisseau sketched a good deal of the decorative detail. His draftsmen polished up Jefferson’s drawings, and to make sure the contractors in Virginia wouldn’t

The drawings and the model were finally shipped off to James Monroe in Virginia, who was urged to make sure they were executed even if it meant tearing down some of the work already done. “Do my dear friend exert yourself to get the plan begun on set aside,” Jefferson wrote Madison, “Sc that adopted which was drawn here. It was taken from a model which has been the admiration of sixteen centuries; which has been the object of as many pilgrimages as the tomb of Mahomet; which will give unrivalled honor to our State, & furnish a model whereon to form the taste of our young men.”

Jefferson never quite admitted that he was the author of this first adaptation of the classical temple form to modern uses. He tried to give the impression that he had merely made suggestions to an established European architect who had drawn up the plan. Patrick Henry was governor of Virginia, and although their correspondence was polite, rightly or wrongly Jefferson suspected that the “great whale” and his friends would oppose any project of his just because it was his.

He had reason to be uneasy because he was far in advance of the taste of his time. His design anticipated by 22 years Napoleon’s rebuilding of the Church of the Madeleine in imitation of a Roman temple. Although there had been small models of temples on the great English estates, as in the gardens at Stowe, the temple form was not put to practical use in England until well along in the nineteenth century. In America, the capitol at Richmond became the prototype from which developed the style of the early republic.

In spite of the efforts of Madison and Monroe, Jefferson’s original plan was changed by the commissioners in charge of construction. The pitch of the roof was altered, a bastard type of Ionic capital was used on the porch, the fluting was left off the columns, and three ugly windows were put in the pediment to give light to the attic. Even so, in its essence the transformed temple remains to this day as Jefferson planned it. From Latrobe’s water color of Richmond in 1796 you can get an inkling of how elegantly the capitol with its high white porch stood guard on its hill over the clapboard houses and the log huts and the shanties and the rattletrap fences of the raw little town at the falls of the James. Monsieur Clérisseau could never have guessed how admirably, translated into wood in the years to come, the Ionic style would express the civic dignity of the republican frontier.

When Jefferson returned from Europe in 1789 his plan was, after settling his daughters with their cousins and aunts, to sail

From his brother-in-law’s home at Eppington he wrote his former private secretary William Short, whom he had left as chargé d’affaires in Paris, to describe the new buildings at Richmond. Way’s new bridge across the James, carried on pontoons and boats, was 2,200 feet long; the locks on the Westham canal were completed. “Our new capitol, when the corrections are made, of which it is susceptible, will be an edifice of first rate dignity, whenever it shall be finished with the proper ornaments belonging to it (which will not be in this age) will be worthy of being exhibited alongside the most celebrated remains of antiquity, it’s extreme convenience has acquired it universal approbation,” he added with understandable pride. It was stirring to see that the building he had worked so hard on had already taken form in stone and mortar.

When instead of returning to Paris Jefferson accepted the post of Secretary of State, he found Congress sitting in New York in L’Enfant’s remodeling of the old statehouse. The adventurous Frenchman’s adaptation of the Louis Seize styles of his native Versailles to the American scene for Federal Hall, as it was called, was to be the forerunner of one trend in American building, as Jefferson’s Richmond capitol was the forerunner of another. In Washington City both styles were to fuse.

Though Jefferson’s political differences with George Washington multiplied as the years went on, the two men found it easy to agree on one subject. That was in the establishment of a capital city below the falls of the Potomac.

As early as his term in the Continental Congress just before he went to France, Jefferson had argued in favor of a federal capital on one of the waterways flowing into the Chesapeake. As soon as he joined Washington’s administration he went to work with the same end in view. On June 20, 1790, he was writing Monroe: It is proposed to pass an act fixing the temporary residence of ia or 15 years at Philadelphia, and that at the end of that time it shall stand ipso facto & without further declaration transferred to Georgetown. In this way, there will be something to displease & something to soothe every part of the Union, but New York, which must be contented with what she has had.

Once the residence bill had passed, Jefferson felt there was no time to lose. He and the President needed no bargains to make them work together for Washington City. They were both Virginians. Always happiest when they looked to the West, they both believed the Potomac valley was the natural route to the Mississippi. Washington, as a dealer in western lands, an accomplished merchant of town lots, and an able promoter, was deeply involved in the Potomac and Ohio canal. Jefferson’s vocation as an architect, his local patriotism, and his conviction that if the eastern and western states were to remain united, a cheap and easy passage through the Appalachians must be opened at once, combined to involve all the great enthusiasms of his life in the project.

When Congress adjourned in August to meet in Philadelphia in the fall, Jefferson and Madison, who was still a bachelor, traveled home together. These jaunts in Jefferson’s phaeton were getting to be increasingly important to both men as their intimacy increased. They could talk as they drove. They studied the flora and fauna. They examined the buildings. They stopped at the best inns. The care with which they chose their meals did not escape the eyes of their political enemies, who would soon be accusing them of scorning their “native victuals.”

They pushed on to Georgetown, where Congressman Daniel Carroll took them riding, with a cavalcade of the local landowners, over the tract of farmland and meadow that lay between Rock Creek and muddy little Goose Creek, which Jefferson already was glorifying by the name of Tiber. After dinner they rowed in a boat up to the Little Falls and admired the romantic beauty of the river. It’s quite possible that, looking back from the water at the richly wooded lands of the saucer-shaped depression which his imagination was already filling with the white-columned porches and the noble domes of the federal city-to-be, Jefferson was able, against the blue highlands of Washington County that hemmed it about, to count seven hills.

When they drove down to Mount Vernon, they were well primed with the lay of the land. The plan of the city was the chief subject of their conversation with Washington. The three of them seem to have agreed that the best site on the Maryland shore was somewhere between the wharves of Georgetown, at the head of navigation of the tidal estuary of the Potomac, and the Eastern Branch, for which Jefferson soon dug up the old Indian name of Anacostia. Jefferson wanted the city laid out in squares (on the plan of Babylon, he said), like Philadelphia, though he wondered whether that city’s ordinance placing the houses at a certain distance from the street didn’t tend to produce “a disgusting monotony.” It is likely that for this conversation with Washington he sketched out the little plat that has come down to us of a gridiron of streets fronting on

Jefferson was in favor of a certain conformity of height and of a harmony of style. He had shipped home from France—now somewhere among the immense number of crates that were headed for Philadelphia—a collection of engravings of the best modern dwellings he had seen in Europe, where he felt builders and architects would be able to find hints for the style of private houses. The public buildings should be modeled on the antique, either in the spherical forms that stemmed from the domed buildings of the Romans, or the cubical that originated in the colonnaded and cunningly proportioned temples of the Greeks. The water front along the shallow Tiber should be preserved for public walks and the houses for government officials.

Washington, as he had shown in his rebuilding of Mount Vernon, had a taste for architecture himself and gloried in the spacious laying-out of grounds. The following month he himself rode round the edges of the marshes and up under the great trees on the hills between Rock Creek and the Eastern Branch to establish definitely where the limits of the city should be. He chose for the federal district a region ten miles square straddling the Potomac. The southern point of the square would include Alexandria and its wharves as far south as Hunting Creek. He hoped to find a way of taking in Bladensburg to the east. As the reporter for the Times and Patowmack Packet of Georgetown put it, the President “with the principal citizens of this town … set out to view the country adjacent to the river Patowmack in order to fix on a proper selection for the Grand Columbian Federal City.”

Next day he rode over the hills toward the northern right angle of the square in the direction of Elizabeth Town (now Hagerstown), where he was received by enthusiastic citizens on horseback and saluted by a company of militia presenting arms amid the ringing of church bells. Bonfires blazed and the windows were illuminated. At a supper served to him at the tavern, the President presented the toast, “The River Potowmac. May the residence law be perpetuated and Potowmac view the Federal City.”

To the Virginians it must have seemed too good to be true. Washington, never sanguine that his dearest hopes would be fulfilled, wrote of his gloomy apprehensions. Jefferson agreed with him that there was a danger that Congress might change its mind. There was no time to be lost.

As soon as he was back in his office on High Street in Philadelphia, Jefferson drew up for the President’s attention a highly characteristic document that stretched Congress’ vague enactment to the point where it could be put to practical use.

Speaking of his conversations with local landowners he wrote:

He went on to suggest various methods which could be used to pay the owners for the land turned to public use without needless expenditure of public funds. He was for playing on their hopes of rising values once the city was a going concern.

Meanwhile the President was appointing a board of commissioners to superintend the work, and a surveyor was being found to lay out the boundaries of the district. As early as February 2 of the following year Jefferson wrote Andrew Ellicott, one of the ablest surveyors of the time, instructing him in professional language how to make his preliminary rough survey along the lines President Washington had decided on. A few days later, in spite of the wintry weather, Ellicott was writing back that he would soon submit a plan “which will I believe embrace every object of advantage which can be included within the ten miles square.”

Ellicott had hardly started to carry his lines across the wooded hills overlooking the Potomac when Washington and Jefferson, in a fever to get sod turned for the foundations, sent frothy Major L’Enfant after him to draw a plan for the “Grand Columbian Federal City.”

Pierre Charles L’Enfant arrived in America at his own expense as a volunteer to fight the British. The son of a court painter, some of whose vast seascapes and battle pieces still hang in the gray light of the royal palaces, he was brought up at Versailles. The father drew designs for the Gobelin tapestry works. The son was trained as a painter.

In America L’Enfant served with credit in the artillery, was wounded in the assault on Savannah under Colonel John Laurens, and discharged with the rank of major. Washington thought highly of him. He was thick with the leaders of the Society of the Cincinnati, who, after the war, sent him back to France to have manufactured for them from his own design the gold eagles which were their emblem.

He was a man of grandiloquent notions with a sense of scale that appealed to Washington. In the Federal Hall in New York he made the first essay toward a distinctive American style. In decoration he was a brilliant innovator, but he doesn’t seem to have had the necessary training as an architect to execute his grand ideas.

As soon as he arrived he wrote Jefferson that he’d reached Georgetown in spite of the sleet and the mud, “after having travelled part of the way on foot and part on horseback leaving the broken stage behind … As far as I was able to judge through a thick fog I passed on many spots which appeared to me rarely beautiful and which seem to dispute with each other who

L’Enfant had with him Jefferson’s modest sketch with its suggestion of an open mall between the President’s house at one end and the house for Congress at the other. As soon as he saw Jenkins’ Hill far to the east, he seized on that as a site for the Capitol, and placed the President’s house about on the spot Jefferson had indicated. He immediately tripled the scale of Jefferson’s sketch. Jefferson had furnished him with maps of a number of European cities, but freshest in L’Enfant’s mind was the plan of Versailles. It was in Versailles that he had spent his youth. So he took Jefferson’s gridiron and imposed on it the arrangement of broad avenues branching out from round points, like the claws in a goose’s foot, which the royal city planners of France most likely copied from the goosefoot of streets branching out from the Piazza del Popolo in Renaissance Rome.

L’Enfant was so impressed by the grandeur of the work and with his own importance as the founder of the city that he quite lost his head. He wouldn’t cooperate with the commissioners. He wouldn’t explain his plans. He suddenly and without warning ordered his men to tear down a house one of the Carrolls had started to build in what L’Enfant decided was the middle of one of his favorite avenues. Before long, to the horror of Jefferson and Washington, who wanted to have the city an accomplished fact before there was too much talk about it, he had managed to flush every local vested interest so that the Georgetown people and the speculators who had laid out lots at Hamburgh on the Eastern Branch and the great tribe of Carrolls were all at sixes and sevens. There appeared a L’Enfant faction and an anti-L’Enfant faction.

He became so embroiled that although Jefferson had sent him Clérisseau’s drawings for the Richmond capitol from which to study details, he never found time to prepare plans for the federal buildings. He had them in his head, he told Jefferson. “I rest satisfied the President will consider,” he wrote,

Houses for the accommodation of government Jefferson and Washington were determined to have. The foundations must be laid before some faction reared up in Congress and squelched the whole grandiose scheme. After some further urging that L’Enfant present the plans he kept talking about but never divulged, they decided to hold a competition. In March, 1792, Jefferson drew up an announcement that the commissioners would offer !500 for a suitable plan for the President’s house.

When few architects appeared to take part in the competition, Jefferson submitted a drawing of his own, in which he set a skylighted dome, similar to the dome that had so intrigued him on the Paris grain market, on a version of his favorite Villa Rotonda. He signed it with the initials A.Z. and kept the secret of his authorship so close that for years the sketch, which remained among the papers of his friend Latrobe, was attributed to an Alexandria builder, Abraham Faws.

The prize was awarded to James Hoban, a young Irish immigrant who had won a fine arts medal in Dublin and been induced to come out to Charleston to design the first South Carolina statehouse. The drawing he presented was eminently practical and had a pleasing modesty which immediately attracted Washington, and Jefferson too. Jefferson was not the man to push his own project. It was part of his gentleman’s code, already quaintly archaic in his lifetime, that a gentleman didn’t claim authorship of designs for a building any more than he used his own name when he wrote in the newspapers or published books. But neither was Jefferson a man to neglect making his influence felt. Much of the architectural character of the White House as it stands today depends on those later additions such as the terraces and the curved south portico which Jefferson either designed or had built under his direction.

When the time came to open the competition for the Capitol, Jefferson wrote the commissioners, as usual putting his own ideas in another man’s mouth, that the President felt that instead of facing the buildings with stone of different colors as had been suggested, he would prefer them faced with brick, possibly above a stone water-table, and using stone for ornament and trim.

“The remains of antiquity in Europe,” he added, “prove brick more durable than stone.” He gave the exact dimensions of the flat Roman bricks. He had measured them himself. “The grain is as fine as our best

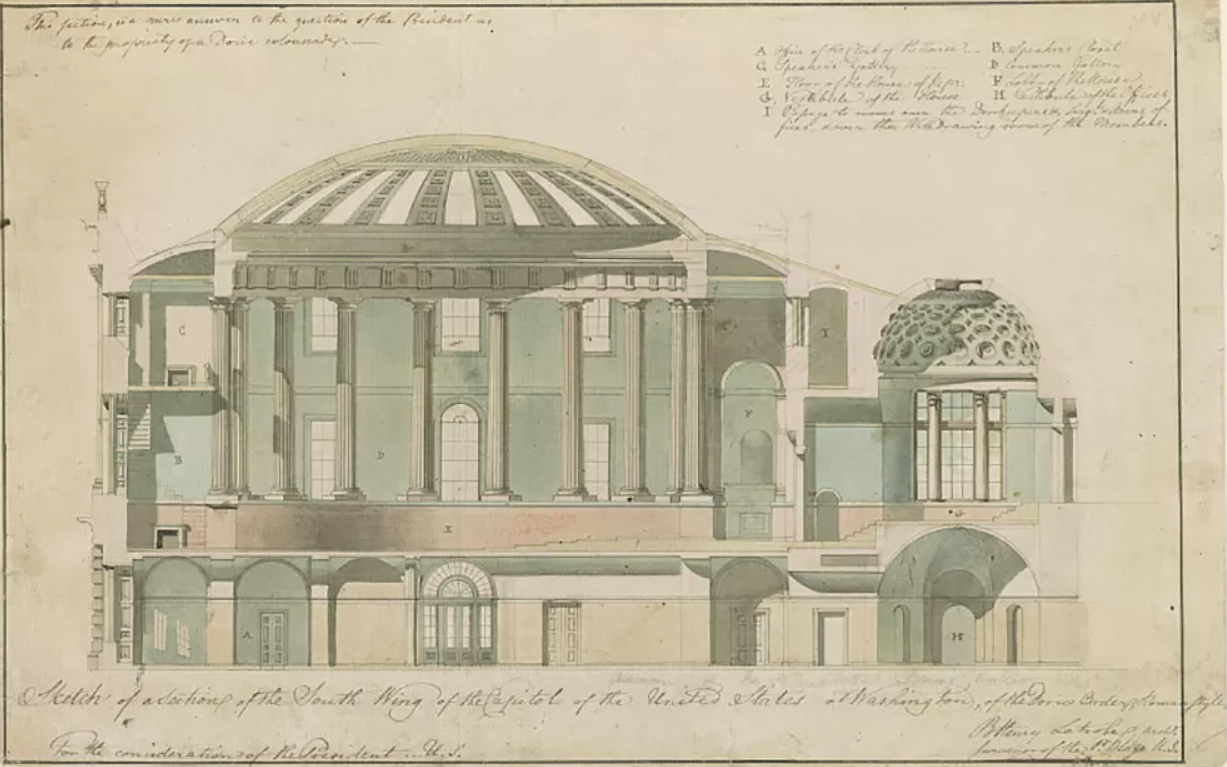

By this time news of the competition had spread through the states. The projects submitted for the Capitol showed an unexpectedly high order of invention. A great period in American building was about to begin. In all the seaport towns, merchants and shipowners and successful sea captains were rummaging in their strongboxes for funds to pay for mansions and public buildings of frame and brick which would express the new dignity of Americans as citizens of an independent republic. Samuel Dobie, who had helped in the building of Jefferson’s Virginia statehouse and may have known that Jefferson had a fancy for this work of Palladio’s, sent in a monumental Villa Rotonda.

Samuel McIntire, already busy ornamenting sea captains’ houses at Salem and Newburyport with his New England version of the style of the Adelphi, worked out a highly accomplished design in the full tradition of the late eighteenth century in England, which some architects still consider his most interesting project.

A man named Diamond, probably a practical contractor with a feeling for brick construction, presented a square building set about a court that harked back even further in English taste, but struck an up-to-date note by indicating locations for water closets. There were some enlarged versions of the Annapolis Statehouse. There were some intriguing experiments with oval rooms. A recently arrived Frenchman whose name was Americanized as Hallet drafted a dome over a pediment supported by Ionic columns, which presented a compromise between the ornate dome of the Invalides and the beautifully simple dome of the Ecole Mazarine in Paris. He had been talking to Jefferson, who wanted a domed building and who had made a vigorous little sketch of his recollections of the Panthéon, the great domed church on the hill above the students’ quarter on the left bank of the Seine.

When the drawings were shown to Washington, the President found only one which satisfied his sense of pomp and his desire for great scale. This was a drawing submitted by a Dr. Thornton, who boasted of being a rank amateur. Jefferson immediately concurred. Thornton had put the antique forms to modern use. The center of Thornton’s plan was a bold Roman pantheon set up on a sturdy set of rusticated arches. It had the New World flavor.

Born of a family of rich Lancashire Quakers on the tiny island of Jost Van Dyke off Tortola in the Virgin Islands, William Thornton had been educated for medicine in Scotland, and being a young man of some wealth had set out on the customary grand tour. He had been captivated by the classical revival and had spent a season in Paris subject to the fascinations of the salon of Josephine de Beauharnais, whom the clinging new tunics in Hellenic style became so exquisitely. He had turned up in Philadelphia in time

Thornton claimed that he had never thought of architecture till he saw an advertisement in a Philadelphia newspaper of a competition for a library. He bought himself some books, fudged a set of plans, and carried off the prize. Now President Washington could think of nothing but his elevation of the façade for the national capitol.

Jefferson agreed. Yet he and the commissioners had already virtually engaged Stephen Hallet and approved his project. It was a case that demanded more than a normal amount of healing oil to keep everybody happy. On February 1, 1793, Jefferson wrote Daniel Carroll, now retired from Congress and a commissioner:

The prize had no sooner been awarded to Dr. Thornton than it became apparent that it would be impossible to erect the building as planned. The columns of the portico were too far apart, there was no way indicated to support the floor of the central peristyle, there was no headroom on the stairways, and important parts of the interior totally lacked light and air. It was up to Jefferson to get the plan into shape.

Hallet had been awarded second prize. Jefferson, who recognized the Frenchman as a competent technician, promptly engaged him to work on Thornton’s drawings. He called in Dr. Thornton, Stephen Hallet, Hoban, and a practical contractor named Carstairs to a conference on ways and means. Dr. Thornton brought along a certain Colonel Williams, who claimed all difficulties could be handled by the use of “secret arches of brick” for support.

Jefferson abhorred the notion, but he kept his feelings to himself. He managed to keep all these gentlemen pulling together to the extent that, by August 15 of the same year, he had a set of workable drawings ready to send on to Washington City. Somehow, in spite of all the burnings and

Meanwhile a miasma of contention arose from the muddy flats of the Potomac. Though many loved him and all admired his talent, nobody could work with L’Enfant. His disregard for money was epic. He was too grand to study ways and means. For him it always had to be rule or ruin. Jefferson wrote tactful letters. Washington sent one of his personal secretaries with soothing explanations to try to induce the Major to co-operate with the commissioners. The secretary was rebuffed. Washington took the rebuff as a personal slight, closed his lips over his uncomfortable dentures, set his jaw, and retired into his implacable dignity.

For years L’Enfant, with his mighty imaginings unrealized, haunted the unfinished city, the first of a long train of injured men waiting for redress. When ElIicott resigned in a huff as surveyor, Jefferson wrote begging him to keep his complaints out of the newspapers. In the end Thornton, too, in spite of the sudden establishment of his reputation as America’s leading architect, joined the ranks of the disappointed. The federal city seemed to devour men of talent.

As Jefferson’s collaboration with Washington’s administration became more and more uneasy, his personal influence diminished at the federal city. The project was beset by every difficulty conceivable. Flocks of speculators rode in, bought lots on borrowed money, took fright in the panic that followed the inflation of the stock in Hamilton’s Bank of the United States, sold at a loss, and were ruined. The streets were a morass. At high tide the creeks backed up into the low-lying lots. Clumps of unfinished buildings moldered in the scrubby undergrowth. There was never enough money to pay the workmen. There were never enough workmen to do the work. When workmen arrived they found no houses to live in.

Washington and Jefferson were both stubborn men. Each in his own way pushed the work on the government buildings on through inconceivable disappointments. It was not till the triumph at the polls in 1800 of the western settlers and the farmers, planters, mechanics, and tradesmen who made up the Republican party that Washington’s survival was assured.

Jefferson as President in the fresh air of the new century was able to take full charge of the work in progress. He appointed Benjamin Latrobe as surveyor of the public buildings. Latrobe was a really great architect, a man of true originality who was able to reconcile Jefferson’s meticulous taste with the grandiose plans inherited from L’Enfant and Thornton. His artistic education had been steeped in the classical revival. In Charles Cockerell’s office in London he had learned to prefer an Attic

After his own retirement Jefferson was to write Latrobe, when at last he too resigned, like the others, disappointed, underpaid, and resentful after having devoted years of his life to the Capitol: “I shall live in the hope that the day will come when an opportunity will be given you of finishing the middle building in a style worthy of the two wings, and worthy of the first temple dedicated to the sovereignty of the people, embellishing with Athenian taste the course of a nation looking far beyond the range of Athenian destinies.”