Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1962 | Volume 13, Issue 3

Authors: Gen. S. L. A. Marshall

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1962 | Volume 13, Issue 3

Editor's Note: General "Slam" Marshall served in both world wars and was the Army’s chief historian in the European theater at the time of the events related here. He wrote many books of military history, including Pork Chop Hill and the American Heritage History of World War I.

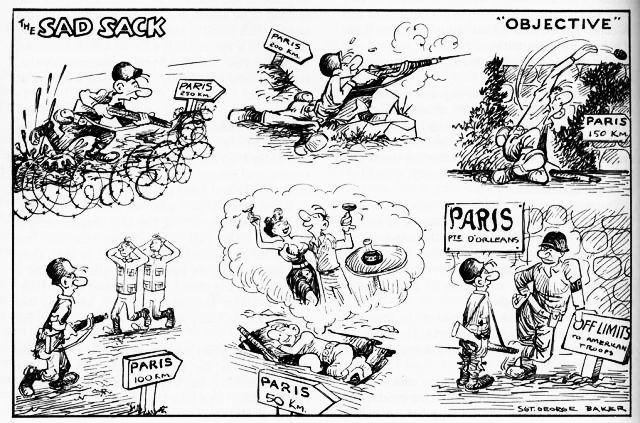

From the war, there is one story above others dear to my heart of which I have never written a line — the loony liberation of Paris.

There are other reasons for this restraint: a promise once made; the unimportance of trying to be earnest about that which is ludicrous; the vanity of the hope that fact may ever overtake fiction; and the light of the passing years on faded notes.

Then, there is another thing — like a sweet dream, yesterday’s rose, or last month’s pay, the event was gone before one could grasp it. From first to last, it was as fantastic as Uncle Tom done by the late Cecil B. De Mille.

When the smoke cleared that night, nine of us dined at the Hotel Ritz. Officially, we were the only uniformed Americans in Paris. That knowledge made us more giddy than did the flow of champagne. There was food fit for the gods and service beyond price. But the headwaiter made one ghastly blunder.

He slapped a Vichy tax on the bill. Straightaway, we arose as one man and told him: “Millions to defend France, thousands to honor your fare, but not one sou in tribute to Vichy.”

He retired in confusion, crying: “It’s the law!” and clutching a $100 tip. It was our finest and final victory of the evening. Then, we did a round-robin signing of menu cards for the benefit of posterity. Among my souvenirs is the paper bearing the signatures of Colonel David K. E. Bruce, Brigadier General Edwin L. Sibert, Ernest Hemingway, Commander Lester Armour, U.S.N.R., G. W. Graveson, Captain Paul F. Sapiebra, Captain John G. Westover, and J. F. Haskell. Above the signatures is the caption: “We think we took Paris.” The date was August 25, 1944.

But we agreed on something else. Hemingway said it: “None of us will ever write a line about these last

Still, there had been a few touches which kept the show earthbound, encouraging the thought that we were not sleepwalking. For our column, the advance ended at the top of Avenue Foch in midafternoon. By then, Paris was almost as free of gunfire as a modern July 4 picnic. So, I walked on a hundred yards to get a front view of the Arc. At least 600 cheering Parisians thronged the Étoile.

As I gazed upward, one last tank shell, out of nowhere, hit the outer edge of the stone pillar 15 feet up. Of the effect on the crowd, there was no chance to judge. The square was absolutely empty before the echo died; the human tide simply evaporated. Not even a gendarme remained to guard the Eternal Flame below the Arc.

Then I looked down the Champs hoping for a sign in keeping with the splendor of the hour. It was there, all right, a great canvas ten feet deep, moored to the top stories of the buildings that faced the Arc and dominating the broad avenue. It read: “Hart, Schaffner & Marx Welcomes You,” the final blessing on a great day. Next morning’s promise was even brighter. By then, a French AA gunner, from a battery which had set up next the Arc, had shot the sign down.

As all who visit Paris know, the Etoile is its bullseye. The great avenues radiate from it like spokes from a wheel hub. And the last street, as one approaches the Arc, Rue de Presbourg, makes a circle around the Étoile.

Toward the freeing of Paris, our final burst of sound and fury occurred along this roundabout. Save for cheering and the popping of champagne corks, the end of the drive along Avenue Foch had been quiet. Arriving at the circular street, the head of the column split, and the French armor and half-tracks deployed around it in both directions in a pincers movement perfectly designed to envelop the Unknown Soldier, had there been any resistance around him. Curious about the next move, I parked the jeep in front of No. 1 Avenue Foch and walked forward.

That was a mistake. Before I had passed two doors on Presbourg, the street was swept in both directions with automatic and cannon fire. The scars from that blast are still to be seen on the Presbourg walls. Some

There was nothing to do but sink back into the nearest window embrasure, suck in my guts, and hope for the best. Through the shot and shell came the Girl from Bilbao who figures in this story. She carried a carbine. She said: “I saw the weapon and knew that either you or John were unarmed. So, I came looking.” What a woman! I pulled her up into the embrasure, and we stood there perfectly helpless.

This mad shooting went on for 13 minutes. When it died, Paris began the return to normal. I went looking for the French major commanding the forward tanks, simply to ask him: “What in the hell are you doing?” He said: “We’re tranquilizing that enemy-held building.”

I asked: “What enemy?”

His reply was positively fierce: “It is defended by the Japanese. We saw them at the window.”

No answer was possible. It would have been as pointless to tell him that he was nutty as to accuse his troops of shooting up Paris real estate to enjoy an illusion of valor. But there was some argument for quitting his battalion at that moment and sitting on the curb.

The show was over. The tanks were moving on to a bivouac in another part of the city. The apartments lining the avenue were now spilling forth Frenchmen laden with pâtés, cold bottles, and frosted grapes. And the jeep had taken two bullets from this last round of foolishness, one getting the windshield, another a tire.

We drank. We ate. We glowed. And there was at least one bit of entertainment. Along the curb opposite, three Frenchmen and one woman suddenly ganged up on one female, rode her down into the street, and were ready to apply scissors to her locks. It was too much for Sergeant Red Pelkey, Hemingway’s driver. He was over there in a bound, kicking the hell out of the three froggies and shouting at the top of his voice: “Leave her alone, goddam you! You’re all collaborationists!”

Amid such diversions, we still sat on the curb one hour later when we saw a small Oriental peering from the doorway of the bullet-riddled building across the street.

I asked him: “Who are you?”

He replied: “Tonkinese—laundryman.”

“What were you doing in the building?”

“Washing clothes.”

“You looked from the building when the tanks went by?”

“Yes, I looked out to cheer parade.”

So, there it was. The major had been right, in a way. We put a first-aid pack on the little man. Unwittingly, he had been a hero of sorts—the last simulated spark of resistance to the Resistance.

Other scenes in this melodrama were no less mad. It is the only argument for beginning at the beginning.

I set it down as an almost inviolable rule that the truly good things which happen to you in war come by accident, like manna out of heaven, rather than because any earthly authority ordered or planned it that way.

Certainly, it was true of my connection with the liberating column. I didn’t belong with the expedition, and I had no intention of joining it for pleasure.

I had been with the two United Stales airborne divisions, the 82nd and the 101st in South England, completing my mission of determining what had happened to them in the Normandy drop. When I left them, they were already assembled in “The Bottoms,” poised for a second jump into France. There was reason enough to accompany them, since the show was certain to be entertaining.

But there was a more compelling argument tor rejoining the First U.S. Army in the breakout, since I hadn’t completed the account of the 1st Infantry Division’s landing at Omaha Beach. The Big Red One had been put through the meat grinder; it was necessary to find out how and why it had happened. So, on leaving my airborne friends, I promised that I would link up with their drop as promptly as possible, and then headed across the Channel, looking for whatever sector was held down by the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry Regiment.

Now, that was where luck began to take hold. The 16th Regiment was in line; its slice of the front was quiet, however, and it was obvious that my work could be  completed quickly. On joining the regiment, I happened to mention to the regimental commander my other commitment. There followed one week of questioning his troops about the earlier operation. On the seventh day, at 9 A.M., I completed my notes and dismissed the

completed quickly. On joining the regiment, I happened to mention to the regimental commander my other commitment. There followed one week of questioning his troops about the earlier operation. On the seventh day, at 9 A.M., I completed my notes and dismissed the

Before I could open my mouth, he said: “I’ve got news for you. A flash just came in over the radio. Paris has just been liberated. Also, there has been an American air drop across the Seine. I suppose you want to hit the road.”

We didn’t take time to say goodbye. Westover, my man Friday, was already heading for the jeep. The hard facts were that there had been no air drop, and Paris was still far from being liberated. But we had to learn these things through trial and error.

At the outskirts of Chartres, a gentleman farmer flagged us down.

He said: “You have a funny army.”

I said: “No funnier than any other army, but why do you think so?”

“Because it isn’t allowed to drink milk.”

“The hell it isn’t; it drinks more milk than whiskey.”

“You’re wrong. I brought out enough milk cans to take care of two battalions passing through. The first company was crazy about it. Then, up came a major who told me your troops were not allowed to drink milk. So, I hauled the rest of it back to the farm.”

He was very sad. I wanted to console him. I said: “You see, old chap, we have in our country a purifying process. Our troops can’t drink milk unless it is pasteurized.”

At that point, he fairly wailed: “Why didn’t they tell me? Pasteur was my grandfather. And you tell me how to purify milk?”

So, naturally, we rolled on away from there. And we had no way of knowing that, before this show was over, we would have to conclude that the great scientist had sired quite a tribe of Frenchmen.

At high noon, we came to Rambouillet. We raced through without pausing for lunch or gas. In fact, we hadn’t even noted the name. Six or seven miles past that fair city lies a small village named Buc. We got within one-quarter mile of it. We approached a wooded hill around which the road twists into the village.

I yelled to Westover: “Stop the jeep!”

He braked, then yelled back: “What’s the matter? Got the wind up?”

I said: “You’re damned right. Did you ever hear anything as silent as this? Not a sound, anywhere along the road. And there isn’t any wire laid along the road. Turn around and barrel. We’re in enemy country.”

That was what we did. Two miles to our rear, we bumped into a battalion of French armor setting up a roadblock at a main intersection. I asked the commander: “Why are you going into position here?”

He said: “This is the front.”

I asked: “Why don’t you go on to Buc? There’s a nice wooded hill just this side of it from where you can cover a spread of

He said: “That’s the point. There are 15 Tiger tanks on that hill part way dug in. We have spotted them from the air. But why fight them if you can turn them? I don’t think we’ll take that road to Paris. Nobody goes to Buc.”

I said: “We went to Buc—or almost.”

While we still talked to the roadblock crew, a jeep, mad with power, came racing into the crossroads from the direction of Versailles. In it were two French civilians and a man in green twill who identified himself as a colonel of the O.S.S. named Williams.

Williams said: “Howdy.”

They had come from a rendezvous outside Paris in St. Cloud with a group of Maquis who led the Paris resistance. Williams recounted the conversations, and got finally to the raw meat: “It’s all wrong about the city being liberated. This morning, another 5000 S.S. arrived and joined the garrison. They intend to fight for it.”

So, this wasn’t quite the afternoon for jumping a jeep across the Seine. One illusion had gone bang, though faith in the report of an American air drop near Paris persisted.

Westover and I doubled back to Rambouillet with the idea of getting a cold bottle and vittles while pondering what to do next. On the edge of town, we saw a Fighting French motor park and turned in with the sole object of putting the jeep under guard while we engaged a beer or two. It proved to be the headquarters of the French and Armored Division, which had beat us to Rambouillet by an hour or so. We learned this when a colonel braced me and introduced himself as General Leclerc’s G-2.

He asked: “Where have you come from?”

Stretching things a bit, I said: “From Buc.”

“Impossible!” he replied. “No one has been to Buc.” So, I told him all that I had heard from his own people and ours—the presence of the enemy tanks at Buc, the position of his roadblock, the news given by Williams that Paris was far from liberated.

The colonel’s eye gleamed. He said: “I must take you to Leclerc. You must tell him all. This is major intelligence.”

Thus dragooned, we met Leclerc, who, even inside his fly-ridden tent, looked and acted like a miniature Mars. Of this dedicated and courageous fighter for France, untimely killed by a peacetime air crash in the Sahara, many hands have written, and my experiences with him were so brief as to add nothing worthwhile.

What stays in my memory is as vague as the impression of a chessy cat minus the grin. The figure was trim and dressed as if for a skirmish. The face was abnormally pink, the eyes steely cold, and the mustache clipped close to vanishing. While I talked, he stood rigid, not even flexing a face muscle. Well, no, that

As I reached the point of saying, “and according to Williams, there are 5000 newly arrived S.S. in the city who will fight for it,” for the first time, Leclerc relaxed.

Putting his hand on my arm, he smiled radiantly, pointed an index finger toward heaven, and said: “Have no fear! I, Leclerc, shall smash them!”

It was a wonderful bit of business, and quite suddenly, I came awake to it. The colonel had introduced me as historian of the United States Army. Leclerc was talking for the benefit of Clio, the Muse of history.

So, I got out my little notebook and I wrote down his immortal words, which are here reported for the first time. On several occasions during the advance, I saw and talked to Leclerc again, but his words were no longer on parade. What he had said was good enough; they typify him; they could serve as his epitaph. His assured presence was an antidote to the contagion of fear, and he smashed the enemies of France at every point where he could lay on.

In the heart of Rambouillet was an ancient hotel delightfully shaded. There, Ernest Hemingway had held forth during the preceding several days while the town was being defended by Resistance members from the French Forces of the Interior. Colonel David K. E. Bruce of the O.S.S., later U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James, was with him. Together, they supervised the irregular operations around Rambouillet, while American units maneuvered in the general neighborhood, but did not close on Rambouillet. Many tall tales have been written about “Force” Hemingway. The real story is good enough. As a war writer, Hemingway spun fantastic romance out of common yarn. But he had the courage of an ox, and he was uncommonly good at managing guerrillas.

In the heart of Rambouillet was an ancient hotel delightfully shaded. There, Ernest Hemingway had held forth during the preceding several days while the town was being defended by Resistance members from the French Forces of the Interior. Colonel David K. E. Bruce of the O.S.S., later U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James, was with him. Together, they supervised the irregular operations around Rambouillet, while American units maneuvered in the general neighborhood, but did not close on Rambouillet. Many tall tales have been written about “Force” Hemingway. The real story is good enough. As a war writer, Hemingway spun fantastic romance out of common yarn. But he had the courage of an ox, and he was uncommonly good at managing guerrillas.

That afternoon, he was away from the hotel. Its surrounding apple orchard swarmed with bees darting at the honeysuckle and big-name war correspondents attacking the apples. There was enough talent in that orchard to cover Armageddon.

Ernie Pyle was there, a bit unsteady, a little teary. It was our last conversation. No, he wasn’t going for Paris; the hell with Paris. He said: “I’m leaving here to go home. I can’t take it any longer. I have seen too many dead. I wasn’t born for this part. It haunts me. I’ll never go to war again. I’ll never let anyone send me. I’ll quit the business first.”

A great little guy. But hardly clairvoyant.

We are still at Rambouillet. What I did not know when I talked to General Leclerc and found him ignorant of his situation was that he

Here, it is desirable to backtrack and explain why things happened the way they did.

There was in Paris a Monsieur Gallois, leader of an especially aggressive resistance group. In mid-August, his forces had started pushing the Germans around, driving them from building to building by fire. The situation became so acute that the Germans asked for a truce, starting the night of August 20 and continuing until noon on August 25. The fact was that General von Choltitz, their commander, did not have his heart in the defense and was stalling for a break which would relieve his embarrassment and save his honor.

Because of the truce, Monsieur Gallois jumped the gun, taking it for granted that the job was done and Paris had been delivered. That was how the rumor built up: on a semi-solid foundation. Like Paul Revere, Gallois mounted his horse and rode to carry the word, heading for General Patton’s Third Army.

From its headquarters, the story was carried to Generals Eisenhower and Bradley, who were at that hour conferring.

On getting the news, Bradley said to Eisenhower: “Let’s send the French and armored in.” That is how the decision was made, according to Sibert, the eyewitness, and that is how it was done. General Omar N. Bradley, for all his native shrewdness and hard practicality as an operator, is at heart a sentimentalist. Months before, while in Africa, he had promised that, if he could have his way, when the hour came to free Paris, Frenchmen would do it.

However, if the high command shared in full the supreme optimism of Monsieur Gallois, it still left very little to chance. The jury-rigged plan which developed around the main idea of passing the laurels to Leclerc’s division was framed with due caution. It made Leclerc’s advance not a road march, but, rather, a major reconnaissance-in-force designed to test whether the Germans intended to stand and fight before backing away.

Leclerc got his orders at Argentan on a Tuesday afternoon. His division was to move to the northwest rim of Paris and there, demonstrate. The clear purpose was to threaten and abort the garrison under Choltitz, if possible, rather than to engage it. For, in the subsequent move, still not entering Paris, the French armor was to make a great wheel around to the southwest of the city, then force an entry in the neighborhood of Sèvres. So doing, it should snare most of the game.

The United States 4th Infantry Division was then a few miles southwest of Longjumeau and much closer to Paris. The plan proposed for it a kind of backstop role, to move, but not to fight. Major General Barton’s mission was supposed to be complete when his command “seized high ground south of Paris.”

The 4th got its

Leclerc’s assigned mission fell apart when he got word of the substantial force of German armor covering the road at Buc. He might have brushed off this block by calling for artillery or an air strike.

But now, there was a palpable reason for changing direction, declining the oblique maneuver to the northwest, and, by wheeling farther south, insuring that he would have to take his division directly into the city. By momentarily risking the appearance that he was avoiding a sham fight, he was gambling that he would get a real one.

However, the change altered the whole frame of operations, whether because the High Command got an exaggerated impression of German strength or because it became dubious when Leclerc took the direct approach. On the next day, the U.S. 4th Infantry Division was ordered to go directly into Paris, instead of cooling its heels on the outside. Everybody loves a race. So it happened that the 4th’s spearhead—one battalion of the 12th Infantry Regiment—got to Notre Dame at noon on the big day just as Leclerc was crossing the Seine. History doesn’t say so, but history is often wrong.

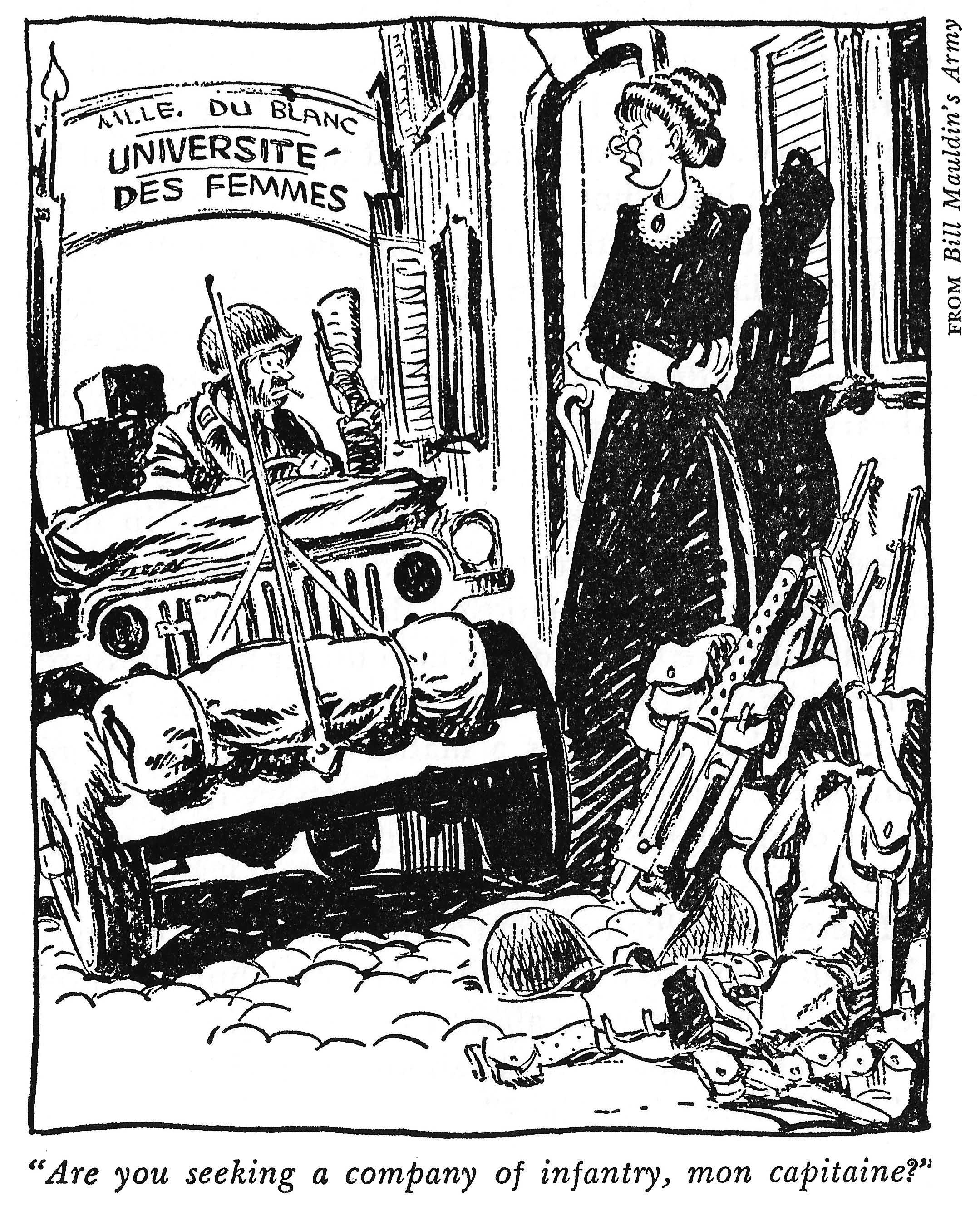

When involved in field operations, a man jellies on the pivot, wondering what to do next. Anything moving in what seems to be the right direction pulls like a magnet. That is how we happened to join General Leclerc’s column headed for Paris. A busy man, he had neglected to invite us. Otherwise, he had been most courteous. But this was not his manner toward all men on that day. According to the legend which blooms larger every time any magazine writer dwells on Hemingway and war, Papa got to Leclerc and told him how to fight his battle and where to expect resistance. There’s no doubt that the contact was made. But, as to what came of it, Hemingway should be the best witness. He wrote: “We advanced in some state toward the general. His greeting—unprintable—will live in my ears forever. ‘Buzz off, you unspeakables,’ the gallant general said in something above a whisper. Colonel Bruce, the Resistance king, and your armored-operations correspondent hastily withdrew.”

In the free-for-all situation, we had no orders. In late evening, we still dallied in the Hotel du Grand Veneur in Rambouillet, having almost given up the idea of joining the air drop across the Seine because the Germans obstinately blocked the road. Four tanks and ten half-tracks passed the veranda, French-manned and headed east. Westover said: “Maybe they’re going

But it was only a short run. The column veered south from the road we had earlier traveled, and, after a half dozen miles, pulled up in a wood southwest of Cernay la Ville. It was the division bivouac. Enough light remained to pitch the pup tent. That night, nothing happened except steady rain and the arrival of an unsteady American major. He was from the staff of the U.S. Fifth Corps, but had somehow lost it. His tone was like a child deserted by mama.

Westover said to him: “The hell with Fifth Corps. This show is headed for Paris. Come along and you’ll have the time of your life. If you’re already lost, two days more won’t hurt. Besides, the boss knows General Gerow and he’ll square it for you.”

The major said a few noble words about duty, then settled down, sleeping under his own jeep. When we were awakened at dawn by hundreds of Frenchmen booming like bitterns throughout the wood, he was all enthusiasm. How could one avoid it? All around us were warriors scuttling about with the eccentric motion of waterbugs, pounding their chests and screaming: “En avant!” Lasting all of ten minutes, that cry pulled us right out of our sacks, and when at last everyone grew hoarse, we enavanted.

By breakfast time, we were already into Cernay la Ville. There, Westover put the jeep around the main body of the armor, and we joined the advance guard as it marked time on a hillside beyond the village. Again, we marched. Chevreuse was already behind us, and the advance guard, made up of a few jeeps and four halftracks, was approaching the airport at Toussus le Noble when we heard the artillery speak for the first time. It was a novel situation. The column stopped in a defile where the road twisted through and over a narrow valley that was steep-sided as a ravine. We could neither back away nor deploy. Off to our left, we counted 23 muffled explosions. To me, they seemed harmless.

I said: “They’re going out.”

Westover said: “Wrong, boss; they’re coming in. There’s something up ahead of us.”

And of course I knew he had to be right about it. For over 40 years, my hearing, though acute to most other sounds, has never been attuned to the pitch of an artillery shell. I’m tone-deaf to explosions, though I don’t know why. Westover knew the sounds as a maestro knows his scale. He had been a forward observer in Italy before I got him. Even in his sleep, his subconscious told him the difference between outgoing and incoming noise.

Behind us, at some distance, a few French guns countered perfunctorily. Then,

It was stall. But not by choice. From directly in front of us, on a beeline, and not more than 1100 yards away, an artillery piece suddenly spoke German. The whizzbang effect said it was an 88. Then, ditto, ditto, ditto. Our little tinclad van was rolling directly into the teeth of an enemy battery. From somewhere to the right of the battery, a 105 millimeter also opened fire; so, from its left, did a heavy machine gun.

These latter items were small change. But the fire from the 88s was a fast strike down the middle. The truck three lengths ahead of us was hit dead-on. Then, a jeep 30 paces to the rear got smacked.

I immediately jumped to the slope of a drainage ditch which paralleled the road. Being more agile, Westover had vaulted it and was in a bomb crater beyond. As for the major from the U.S. Fifth Corps, he had jackknifed beautifully straight into the muck of the ditch bottom. He arose looking like a refugee from a sewer. He said: “I’ve been thinking it over. It was wrong of me to come along. I must return to my duty.” He turned his jeep around and somehow managed to swing out past the armor. We never saw him again.

No one has ever managed to diagnose the emotions of fish in a barrel. It could have been that bad, for the shelling continued. But the German battery was getting nervous. Its stuff began going wild. Westover was much more comfortable in his bomb crater than I was, flattened on the bank of the roadside ditch. Since the battery was aiming straight down the road, and the ditch ran parallel to it, clear to the guns, its bank offered only relative mental peace.

Forward along the road about 150 yards, and that much closer to the battery, was a ruined building, partly wrecked by earlier air bombings and now smoking from a hit. But its stone walls still stood, and beckoned. There lay sanctuary from the spite of the enemy, and even more from his noise. So, I yelled to Westover: “See that building! That’s where we’re going. Get moving!”

Nothing in life is stranger than the way in

Not knowing it, I was at the point of change as we drew near the wrecked building. Its immediate setting and some brightness in the decor suggested that it had been a café. One shell from the battery had knocked the sign from above the door some minutes earlier. We turned it over. It said “Clair de Lune.” In the years since, I have loved this piece of music steadily and passionately. Had we not turned over the sign and read it, my feelings would be as before. But there was a charmed hour within the strong walls of that old café, though why those moments were high, I cannot say, except that they were sweet and friendly and became the portal to a delirious adventure.

Inside, the café was what reporters describe as a shambles, though I have never bothered to learn what a shambles might be. Part of the wall was blown in. The furniture was all either smashed or overturned. The floor was littered with empty bottles, shattered china, and cruets. The air hung heavy with the mingled aromas, neither pleasant, of horse manure and stale beer.

While we looked and poked about, hopeful of finding a name brand to be plucked from the burning, there came from under the overturned bar the lowthroated chuckle of a woman. There was something very pleasant about it, as if she were laughing at us, not because we looked funny, but because that was the best way to greet another human.

We turned the bar upright, and she stood. It is enough to say how she looked on first sight, since she did not later change. She was small and slight and much too ill-clad and dirty to be described as a gracious figure. Her dark face was marred by conspicuous buckteeth. The eyes were brown almost to blackness. Her hair was tangled and hung stringily halfway to her waist. Her gown looked like a cut-down Mother Hubbard, once black, faded to gray, and frequently slept in. Such was Elena, and she was just 18. But no unkempt damsel ever wore a warmer and less embarrassed smile. I will give Elena that, adding also that her courage made her seem beautiful during the two days we knew her.

The reason for these rough-hewn details is that the great American novelist was later to picture her as a gorgeously bewitching siren who held every man of the column in the hollow of her classic hand. Also, he made of her a profound philosopher, spouting great words about noble causes, whereas I have known few women who have had such an appalling gift of reticence. That was for Collier’s, but it was also for the birds.

Elena’s first words were: “What is American opinion of Marshal Pétain?” So help me—that was what she said even before she had tugged at a stocking or straightened her dress. A most unusual woman, though the strangeness of her mental processes was no more startling than the irregularity of her speech. A light dawned. Since her French was almost as abominable as my own, she too must be a stranger.

I said in Spanish: “You are not French?” (We never got around to saying how Pétain rated back home.) She grinned proudly and replied: “I’m from Bilbao. I came here to fight with the resistance. My man is F.F.I. He’s somewhere out in front of this column.”

As she said it, Hemingway came through the door. We had last talked at Key West in 1936. But it could have been yesterday. Like Elena, Ernest wasn’t saying any on-stage words for history. He simply yelled: “Marshall, for God’s sake, have you got a drink?” I said: “We’ve ransacked this place; we don’t have; we have not.”

Westover spoke: “Boss, there’s a fifth of Scotch in your pack back in the jeep. You put it there three weeks ago and forgot it.” I said: “OK, Big Mouth, for having such a good memory, you can walk back through that fire and get it.” He did.

One of the minor surprises of war is the great thirst on the part of any group of fugitives from the law of averages. With Elena helping—I had just introduced her to Hemingway—that Scotch soldier was dead within 20 minutes. So, by then, were quite a few members of the German battery, the French artillery having at last gotten the range.

But that isn’t how the story came out in Collier’s. Here’s how Ernest saw it: “I took evasive action and waded down the road to a bar. Numerous guerrillas were seated in it singing happily and passing the time of day with a lovely Spanish girl from Bilbao whom I had last met at Cognières. This girl had been following wars and preceding troops since she was 15, and she and the guerrillas were paying no attention to the (clash) at all. A guerrilla chief named C— asked me to have a drink of his excellent white wine.” Ah there, romance! And isn’t it fun to be a pack of guerrillas once in a lifetime? Who’d have thought it?

We were soon joined by a character with the nom de guerre of Mouton, leader of the local F.F.I. His real name was Michel Pasteur. This particular scion of the great scientist was about 35, tall and spare, with flaming red hair and sky-blue eyes. He had the stride, carriage, and dress of a

Mouton grunted, belched, and pointed left. We took it to mean that we were to prowl outward through the ruined hangars toward the German machine gun to see if it was still chattering. By then, we were all feeling hardy as lions. Hemingway said: “If we get in any trouble, I will take care of you,” which gave Westover such a giggle that he almost split his Silver Star ribbon. Such cracks were a habit with Ernest, due to his owning the copyright on war. There were other reasons why he was called Papa, but this one was good enough.

Because of the slough, the knocked-over hangars, and the wreckage of two B-29’s, we didn’t get very far very fast, and finally, the way was blocked wholly. It was then that Hemingway said: “I think we ought to patrol all the way if you’re up to it.” Mouton grunted. Again, Westover laughed. Together, we shagged back to Clair de Lune; there was no further mention of patrolling.

It was all so like Papa. He would still have tried to amble forward had anyone picked up his idea; that he might have been shot for his pains was immaterial. He loved soldiering, with reservations. Being in an armed camp exhilarated him, and he had a natural way with the military. The excitement and danger of battle were his meat and drink, just as the unremitting obligation to carry on was his poison.

To put it more accurately, he loved playing soldier on the grand scale, with shooting irons. Yet, in him, it was not a juvenile attitude. I truly believe he played at it more because he enjoyed the game than because he was interested in studying men under high pressure. There was this difference in view between us: I have always looked at war as a matter-of-fact business, requiring the rejection of every unnecessary risk and the facing of any danger along the path of duty; a man fully aware of his genius can afford more than that.

There was sudden motion at the front of the column. No signal came to us at the wrecked café, but somehow, we sensed that we were about to move again.

Hemingway said: “What about the girl?”

“Well, what about her?”

He said: “She can’t be left here. The countryside remains in German hands. The column is only mopping up a highway. Leave her here, and she may be killed or captured.”

That was how we came to welcome Elena aboard the jeep and why it happened that a Spanish girl held high the first American flag that went into

The column was still in a defile, made so by the quagmire on both sides of the road, where once had been an airfield. In the van of the column were jeeps and trucks. Perhaps 500 yards forward of the first vehicle, the earth flanking the road became solid. There, we could fan out and deploy in line. The German battery was still firing feebly, and with the occasional rounds from the 88s was mixed supporting stuff from an automatic gun and a few rifles.

Out of this unique situation came the weirdest order of attack that I have ever seen in any military operation. We advanced with jeeps in line first, followed by trucks in line, followed by half-tracks, followed by tanks. In the circumstances, there was no other way to thin out the formation. Then, as the unarmored vehicles began to spread over the open fields, the half-tracks and tanks, gripping on solid ground, would swing out and around, pinching in toward the battery from both sides.

That is how it was done, and, looking back now, I would say that had any safer, saner movement been possible, it would not have suited the hilarious nature of that thoroughly madcap adventure.

From where we rode, the prospect could be faced cheerfully. We were the next to the last jeep with the advance guard. The road ahead, at the point where the jeeps ahead of us would begin to spread out to either side, was shaded by a straight line of Lombardy poplars all the way to the battery and slightly inside of it. So, when the other jeeps deployed, we could hold the road and hug the line of the trees. It was a very satisfactory bumper guard, now that the battery was dying.

Silly as it sounds, the thing went off well. We were within 500 yards of the guns when the finish came. The tanks and half-tracks completed their sweep, firing like crazy. No white flag was waved. No shout was heard. Suddenly, we saw 20 or 30 Germans come out of that nest and stagger across the open field toward us, hands in the air. Only one man couldn’t because one of his hands and the other arm had been shot away. Still, he reeled along. Others were bleeding from the chest, head, shoulder, and legs. These things we saw as we drew abreast of them.

But no one minded or paid the slightest heed. They were walking past us into nothingness, and we were again back to the road with everyone straining toward Paris. Some must have continued this march macabre until they perished from bleeding. I have seen no uglier sight in combat than this.

That sudden decision to pick up Elena and take her to Paris had unlimited romantic consequences, not at the moment foreseeable.

Elena was the innocent catalyst, rather than the prime

But night must fall, and Frenchmen must think of things other than war. A late moon found us bivouacked in the gutters opposite the Renault plant on the wrong side of the Seine, and by then, there was not a tank, half-track, or truck in the column but bloomed with women. Each frowning turret looked like a beauty-parlor ad, and the squealing within and around the hulls did not come of grit in the bogie wheels. Leclerc’s mobile division had suddenly doubled in size while losing half of its fighting power.

I will get back to the calmer workaday entries from my diary of the loony liberation soon enough. There is one concluding note on the feminization of the French and the armored. Five days after the liberation was complete, Leclerc was still trying to get the women of Paris out of his tanks. The division bivouac in the fields out along the Soissons road looked like a transplanted Pigalle under arms.

Memory’s a witch. Thinking back, I would have sworn that the German battery at Toussus was overwhelmed in a breeze, with no loss to our side. But, thumbing through my faded notes, I find this entry: “As we advance, one French half-track, turning into the battery, is hit dead-on. Ahead of me, an overloaded weasel takes a direct hit from a shell. Our losses, six killed and 11 wounded.”

We churned on to Jouy-en-Josas. There, the column blocked and stopped as the van started uphill through the main street. We were hard by the railway station, and, for five minutes, the wait was joyous. Out poured the townsfolk, arms loaded with cold bottles of champagne. Mothers lifted babies to be kissed, only to be crowded out by the younger beauties of the place, who had the same general idea. Old soldiers who looked like relics of the Franco-Prussian war lined the sidewalks at stiff salute.

Then the music started. The Germans had a heavy mortar battery in a nearby chateau and, behind it, two field guns. Three French tanks charged the battery position; one was knocked out. The others finished the action.

We moved up to the main street and again halted. Twenty-one German prisoners, several of them wounded, all of them captured in the fight around the chateau, were brought back to be paraded down the main street of Jouy-en-Josas. About 60 Frenchmen of the advance guard formed, facing each other within the street, holding aloft their rifles, mess gear, or any hard object that was swingable. As the Germans entered this gantlet, the Frenchmen cracked down

We were in motion again, and shortly, we made a sharp right turn onto a main avenue three kilometers east of Versailles. The road ahead was a mass of greenery, its surface blocked by a half-mile-long line of felled sycamore trees. The French tanks moved uncertainly into this stuff. Four hundred yards off to our left was a dense copse. Out of it suddenly a man came running swiftly, screaming into the wind as he ran.

I asked Elena: “What’s he saying?”

She said: “There’s a German antiaircraft battery in that wood. Three guns altogether. And they’re ready to open fire.”

So, with the way partly cleared, we sped ahead, looking for the commander of the forward tank battalion to tell him he was about to be smacked broadside. With every second counting, he still might have gotten his tanks around. At least he listened respectfully. Then he answered: “I know all about it; we’ve already taken care of that battery.”

Never was an overconfident statement more beautifully punctured. It came like this—Boom! Boom! Booml At 400 yards point-blank, the Germans couldn’t miss. Behind us, there was loud screaming. One vehicle on the pivot exploded. Another burst into flame. Said the French major: “So, now we know.”

So much for the legend that intelligence supplied by Hemingway, with an assist from his two adjutants, Mouton and David Bruce, enabled Leclerc and troops to slip through to Paris, skirting the nodes of resistance. Nothing nastier could be said of the operation; not one sign of applied intelligence distinguished it.

During this and the succeeding scenes, our great and gentle friend, Papa, was close beside us, right to the finish. Blessed be his memory, and hallowed his reputation for fighting gumption; they should not be sullied with canards like this one from an American magazine:

Behind Papa’s jeep wheezed the long line of Renault sedans, taxis, jalopies and trucks, all of them crammed with Task Force Hemingway fighters, now numbering more than 200. “We’ll tag along with Leclerc as far as Buc,” Papa said, “then near Versailles, where our information shows we will be slowed down by resistance, we’ll swing around and come into Paris by a back road one of our bike boys found. The chief of staff didn’t think the road was quick enough, but I do.”

Well, glory and hallelujah. Papa stayed with us, then and later, never breaking away toward Versailles. His only attachment was Sergeant Red Pelkey, his jeep driver. Leclerc’s boys acted like nitwits, but, if they were slowed anywhere by resistance, it came from the mademoiselles, not the krauts. Papa deserves more credit than he has been given; he was not one to force his talents beyond their natural limits.

Our final lurch, after the column had swung past Orly Field and then, turning leftward, entered the solidly built-up area south of the Seine, took 24 hours.

Through the whole ride, we were as perverse as possible. We tore madly along, when reason whispered that we should proceed with care. We stalled insensibly whenever the way seemed wide open. It was less a fighting operation than a carnival on wheels. Take what happened after the German battery, concealed in the copse just off our flank, ripped the column broadside; Rather quickly, tank fire killed that battery. The jeep had pulled up between two medium tanks. In the shuffling which attended the exchange of fire, the tank behind us moved forward a few yards. It became impossible to turn. Then, both tanks resumed the advance, and we went along between them willy-nilly, rather than be run down. This proved embarrassing. In A half mile, our route turned left, at which point we headed straight toward the Seine.

Right at the junction, with the closest piled explosives only 20 feet from the road we had to take, was a block-long German ammunition dump. The stacked shells were already blowing sky-high, and, even at a distance, the smoke, blast, and flame seemed like an inferno. For that, we could thank the killed-off German battery. With a final round or two, it had fired the dump just before being knocked out of action. So doing, it had blocked the road, or at least that was what we supposed for the moment.

The lead tanks came to the intersection. There was not even a pause for a close-up view of the danger. They wheeled left and advanced in file right across the face of the exploding dump. Its metal showered the roadway and its heat was like a blast from molten slag.

For the people inside the tanks, the risks were trivial. They had battened their hatches, and the plate was thick enough to withstand the hot fragments. They did not take it on the run, as they should have done; they snailed along at about six miles per hour.

I yelled:

Westover yelled: “We’ve got to, or the tanks will crush us. They’re not stopping for anything.”

That’s how it was. The jeep-loaded people spliced into the tank column were held feet-to-the-fire by their own friends. That Mazeppa-like ride lasted not more than 40 or 50 seconds by the clock, but the clock lied. There was no protection against either the flying metal or the infernal heat. The best one could do was cover his face with his arms, double up so as to compose as small a target as possible, and hope for the best.

We pulled out of it whole-skinned. One shard had smashed through the hood of the jeep. Another had smacked the metal panel next the jump seat, missing Elena’s bottom by inches. The quarter-ton still perked. It was hellishly hot, and we were horribly thirsty.

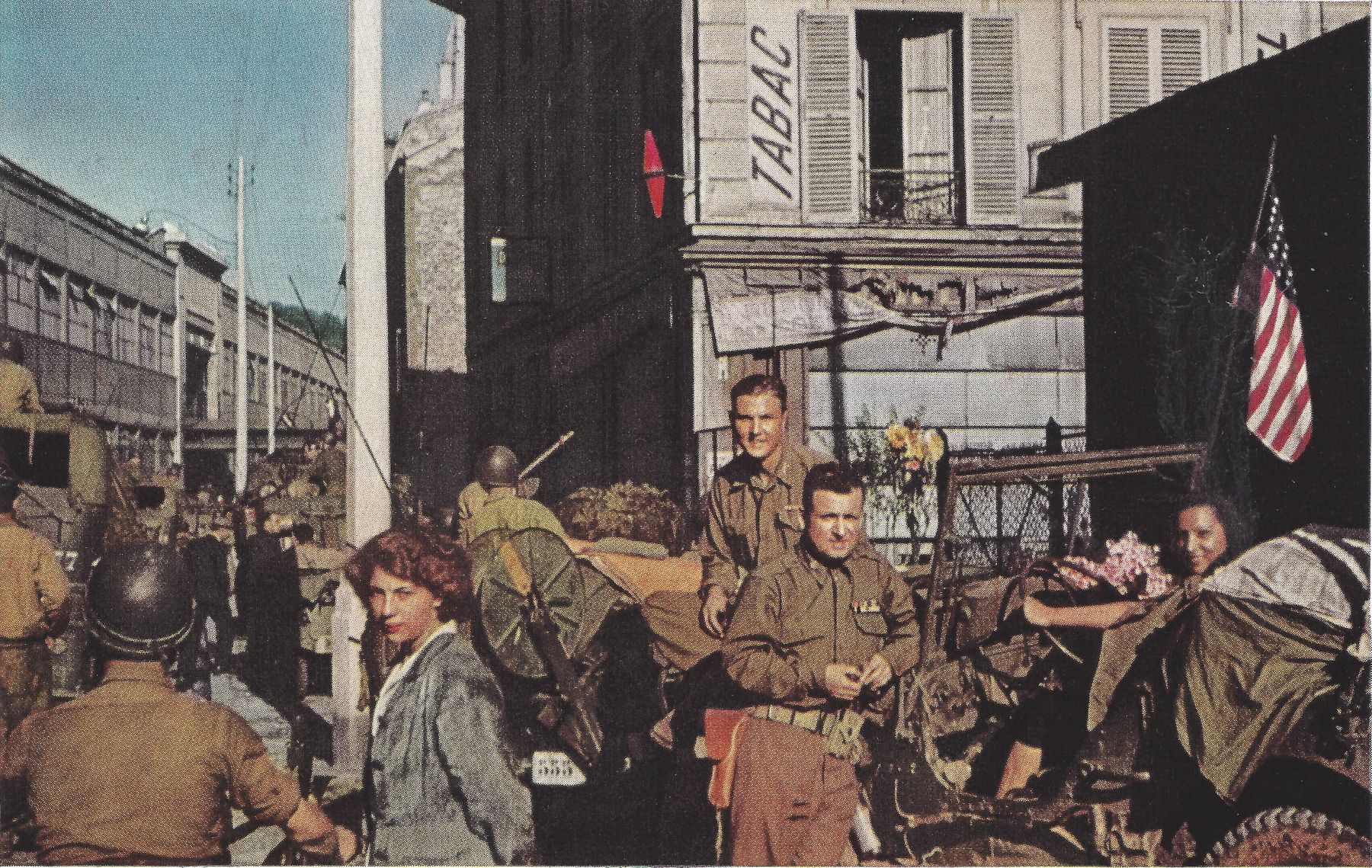

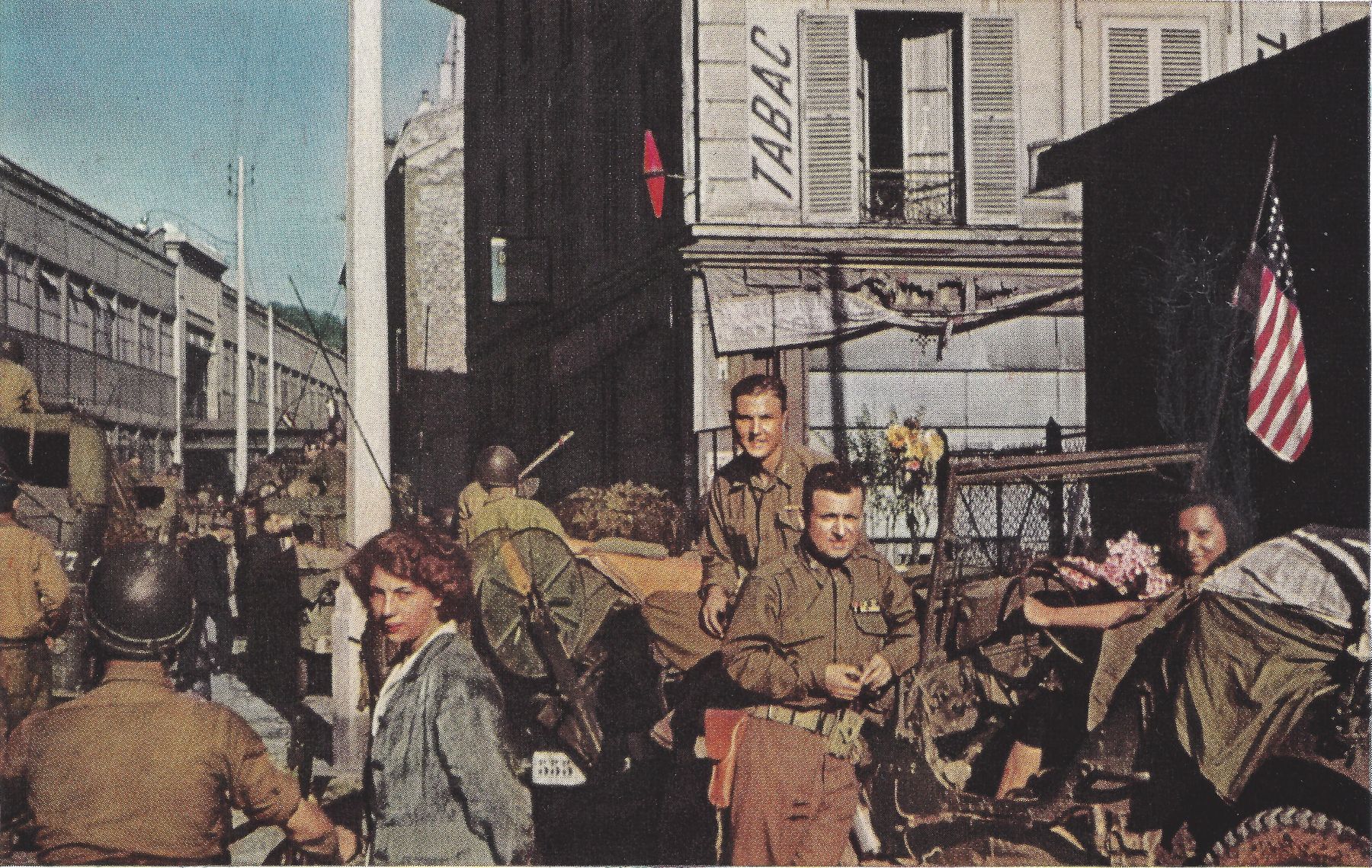

There was not far to go. Where the dump ended, the metropolitan city began. In a twinkling, we were among houses and stores, and banking both sides of that broad, lovely avenue were the people—and what a people!

They had waited four years for this parade, and they were ready with the vin d’honneur and much more. There were again the Old Guard standing at salute, wearing faded kepis and freshly shined medals, young mothers rushing out with infants to be kissed, more beautiful blondes and brunettes, and some not so lovely, platoons of urchins screaming and frantically raising their hands in the V-signal, dear old gammers showing their petticoats when they raised their skirts to weep, and everywhere, men and women, shouting, laughing, crying, embracing in ecstatic delirium.

It was about then that Westover pulled a folded star-spangled flag from his pack, mounted it on a pup-tent pole, and gave it to Elena to hold high. That small gesture of pure patriotism was the great mistake. Right then, the unattached females along the march route began climbing into Leclerc’s tanks and half-tracks to stay. Elena had challenged them. It was time to strike a blow for France. And they didn’t have any flags.

There was no way to refuse that mass of mad humanity. So, there were countless stops and starts by the column. Repeatedly, the people surged onto the avenue and stood solid until the armor ground to a halt. But, when they rushed the vehicles, it was not to pour champagne, cognac, and Calvados. They dumped the bottles whole, the champagne chilled, the hard stuff still uncorked. When the jeep at last reached the bank of the Seine, it was carrying, like coals to Newcastle, 67 bottles of champagne on a run into Paris. We gave it back to other Frenchmen. As I said, everyone was a little cuckoo.

Papa Hemingway was still with us, and very busy, not instructing the F.F.I. scouts, advising Leclerc, or bending the elbow. Like a happy tourist, he was snapping pictures of everyone and anything

That night, we bivouacked on the broad avenue, about 100 yards short of the Pont de Sèvres, directly across the Seine from the Renault plant. From the Longchamps race track, the German artillery tried to bring the column under fire, but the closest shells hit high on the ridge running off in the direction of Versailles. Through the night, our tank destroyers returned the fire from positions along the river bank.

All morning long, the column chewed its nails, but we couldn’t cross the bridge before we came to it. The generals behaved like union men honoring the noon whistle. At exactly 12:00 on August 25, 1944 A.D., we cranked up and rolled across the Seine at Pont de Sèvres. But for occasional out-of-bounds rounds plunked into the rollicking scenery by the German batteries at the Longchamps course, there was nothing to remind us that the advance was a military action and not a pictorial parade into pandemonium.

Scouts and heralds, with trumpets and dodgers, must have been sent forward to muster the crowd. For Paris was already alerted to the entry and had cast off its chains, though formally, the Germans still held the city. For the first mile or so of the march, there was repeated the wild, high carnival of the prior afternoon, except that the crush had thickened and was less controllable. In our jeep, we gulped and we wept. Elena had lofted the American flag, and the sight of that banner, more than all else, stirred the beholders to the highest pitch of ecstasy. Again, the mothers came running with babies to be kissed, the aging ex-poilus stood at salute, the little boys screamed for cigarettes, and the champagne-donors rushed the vehicles. But the Paris mob was a little different, better prepared, more sophisticated. Skirts were shorter and hair-dos more conspicuous. Photographers and autograp-hunters pressed in close.

Place St. Cloud is the first roundabout beyond the Sèvres bridge. As the jeep turned into its spacious circle, the column suddenly stopped dead. We could not see why. The clamor had ceased. The central garden of the circle was utterly deserted, as was its outer rim, which was built up solid with apartment houses. That one moment was pregnant with silence, made more awesome because there was no explaining it.

Then, two things happened right together. A volley of rifle fire erupted directly behind us, and an artillery shell out of nowhere struck and felled a chestnut tree on the parkway, so that it fell as a screen between the jeep and the nearest apartment building, 30 yards to our right. In those few seconds, while the tree was settling, the tanks and cars ahead of us became emptied of their people (including Hemingway) as they ran for the buildings on the far side of the circle. Such was the effect of the surprise fire. We couldn’t follow the stampede. All

Punctuated by random rifle fire, this interlude lasted not more than five minutes. Then, there was a roar and rattle in the direction we had come from. Six French half-tracks, followed by five tanks, raced into the circle and, turning inside the stalled column, continued around and around the circle with their machine guns wide open, blazing at the building we were facing. That fire grazed just above the jeep and stripped every twig and leaf from the upper part of the fallen tree. There was nothing to do but hug the handiest gutter and curb. Westover sang “I’ll See You Again” through his teeth, which was always his habit when the wind was slightly up - a sign that he was thinking of home and Eloise. The Spanish girl said: “Tengo mieda much,” and laughed like hell to prove it. She was worth any ten duchesses in such moments. We knew great fear and high excitement exquisitely mixed, for it was touch-and-go whether we’d come out. The shooting stopped when there was nothing left to fire. We were whole-skinned and not yet shaking. The entire thing was stark mad, our escape due to pure luck.

The tanks pulled off. The place quieted. We heard a man yelling from a great distance. Then we saw him, and the sight was more whimsical than all else. He was on the third floor balcony of the apartment building across the circle, and he was hunched far over as he scuttled along. “Looks like Lon Chaney haunting Notre Dame,” said Westover. The man shouted in French, but, though he had his hands cupped, the words barely cut through the wind. But we knew the voice. It was Papa again.

“What’s he saying?”—this to Elena.

She answered: “There are Germans in the building behind us. We have to get out. The French are bringing in artillery to blow the place down.”

We got out. Elena went first, taking those 80 yards like a startled doe, we following at 20-second intervals, with Westover coming last so that he could cover the windows against snipers during the getaway. Not one hostile round dignified the extrication. When we made the portal on the far side, there was Papa with his carbine at shoulder, laying down the covering barrage. That was a big building, and he could hardly have missed it. The French artillery duly arrived and did its sterling stuff. Whether there were ever any Germans in the apartment, or whether the fire had come from a few rascals

Soon after the column had its last hurrah at the head of Avenue Foch, we said goodbye to Elena. A French major came down the line screaming: “Get these ____ women out of the vehicles.” That had to be resisted, since the honor of a very gentle person was concerned. So, the major was told off, loudly, profanely. From behind me, a voice roared: “You tell ’em, Marshall. Since when hasn’t a soldier the right to company in his sleeping bag? That’s the way I won____,” but the name was lost in the roar of approval from the crowd. Papa’s wisecrack got to Elena, where the major had failed. Without a word, she slipped away to seek her lover, and we never saw her again.

From the Étoile, John and I drove on the short run to the Hotel Claridge. We were tired. The desk clerk refused us a room, though the hotel clearly was untenanted. We demanded to see the manager.

He said: “There are no rooms. This hotel is reserved for the German Army.”

I said: “You’ve got just five seconds to get it unreserved. This is the American army moving in.” We got the rooms and quickly learned the reason for the attempted stall. Each bathroom bore a neat sign bidding warm welcome to German officers. The embarrassed host had wanted time to remove them.

The story was told at the clambake in the Ritz that night, which put it in circulation. Jack Ritz commented drolly: “What could you expect? Hotel men have no country. They’re the only true internationalists.” That is the probable basis of the greatly embroidered legend about Hemingway liberating the Ritz. Wrong hotel. Wrong cast. I know Jack was waiting there with Dunhill pipes as souvenirs for each of us when we made the Ritz lobby, slightly ahead of Papa.

Until the last dog was left unhung, the grand event had these overtones of opéra bouffe. Von Choltitz, the enemy commander, had his headquarters in the Hotel Meurice, that monument to the rococo. In early evening, a tank went by the Meurice, fired one round at an ancient Chevy parked alongside, and set it afire. That was enough boom-boom to save Choltitz’s honor. He and 20 of his staff officers came running from the hotel, hands in the air. Choltitz, with his boys stringing along, was taken to Montparnasse, where Leclerc told him to surrender the 20 spots where Germans still held out. Captain Paul Sapiebra, U.S.A., wrote out 20 copies of a surrender order, and Choltitz signed them. The 20 staff officers were then loaded in 20 jeeps and speeded to 20 points of resistance.