Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 3

Authors: Herbert Mitgang

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1971 | Volume 22, Issue 3

In the summer of the year 1944, in a time of world war that is already history to my children’s generation but remains vividly personal to mine as a moment of (in retrospect) astonishing simplicity and idealism, I found myself pointing a jeep in the direction of Pisa and Florence. On the so-called forgotten front in Italy, the Wehrmacht held the northern side of these cities; the line dividing their riflemen and ours was the river Arno.

The big show of the European war was being played out on the newly opened second front in Normandy. Along the French Riviera a diversionary side show became popularly known as the champagne war. Since the German 88’s had not been informed that our Mediterranean theater had lessened in strategic importance, they were still to be reckoned with.

My windshield was down and covered with tarpaulin —any fool knew that glass reflected and could draw artillery fire or even a Luftwaffe fighter seeking a target of opportunity. I was driving along happily and singing to myself because all I needed was in that jeep: a Springfield rifle, a scrounged .25-caliber Italian automatic, two large cans of gasoline, one helmet (I wore the liner as a sunshade and the heavy steel pot, useful for shaving and washing, rattled around in the back), several days’ worth of C and K rations, five gallons of water and two canteens of vino, and—most important of all—one portable typewriter.

That little Remington was the telltale of my military trade: I was an Army correspondent for Stars and Stripes, Mediterranean. Below the masthead of two enfolded flags its only mission was inscribed: “Daily Newspaper of the U.S. Armed Forces published Monday through Saturday for troops in Italy.” Although we were occasionally enjoined to do so, we were not supposed to propagandize, publicize generals, or even inform and educate. Our job was to put out a newspaper as professionally as we could. Although armed, the soldier-correspondent was not necessarily expected to go looking for the enemy but instead to report about the soldiers, sailors, and airmen who did.

As I drove along the seacoast road, noticing the island of Elba at one point but without worrying about Napoleon or anyone else’s war, the parting words of one of the correspondents came to mind. “Don’t forget,” he said, “your job is to get back stories, not get yourself killed.” Two of my colleagues, Sergeants Gregor Duncan and Al Kohn, had died covering the front, and all of us were shaken up when what was an

There were stories everywhere. My immediate problem was not to be distracted before reaching the Fifth Army’s pyramidal tents. Ernie Pyle, whose influence as the most important single reporter at home and abroad of the Second World War cannot be exaggerated, had dignified the GI and the “little picture” in his syndicated newspaper column. I recalled having a drink with Pyle near the end of the Tunisian campaign in North Africa and could see part of his strength as an ingratiating reporter. He was skinny, wet, and shivering—a civilian version of the rifleman without rank, and therefore to be trusted.

None of us on Stars and Stripes deviated very much, or cared to, from his kind of reporting. Most of our seasoned front-line reporters, such as Jack Foisie, Ralph Martin, Stan Swinton, and Paul Green, roamed the field as Pyle did, covering not only battles but the “mess-kit repair battalions” (as the stray outfits were jokingly called) that supported the infantry. When I saw a sign that intrigued me—an outfit running a GI laundry somewhere near Leghorn—I stopped briefly, made a few notes for “flashes,” chiselled some gasoline for my half-empty tank, and remembered to keep going.

After getting a tent assignment and a briefing at Fifth Army headquarters, which was located in a forest near a village somewhere between Pisa and Florence (whose name I cannot recall, though I vividly remember a long evening’s talk with the parish priest about the art of the carillonneur and how his bell ringing regulated life and death), I decided to look in on something called an “armored group.” It consisted of a self-sufficient group of tanks, artillery, engineers, and riflemen—a forerunner of the integrated, brigade-size units several chiefs of staff assumed would work for the brush-fire wars of the future.

The artillerymen appeared to be most active that afternoon. They were maintaining their franchise by firing harassing shells across the Arno. I took my names and hometown addresses, listened to the battery commander explain his “mission” in stiff Army lingo, and then accepted the captain’s invitation to try out the armored group’s mess for dinner. What happened next sticks with me as an example of the confusion that existed right in our own theater about Stars and Stripes correspondents. I immediately noticed that the two long tables were divided between field-grade officers (colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors) and company-grade officers (captains and lieutenants). The colonel directed me to sit with him and motioned the captain to sit with his ignoble kind.

See also: "Remembering Ernie Pyle," by Gil Klein

There was only one slight error in seating rank here: I, like most correspondents on Stars and Stripes , was a lowly sergeant. By

The reason for the confusion was that we carried a patch on our left sleeve saying “Stars and Stripes,” without any mark of rank. This was by design. I recall a meeting of the Stars and Stripes staff in the Red Cross building on the Boulevard Baudin, Algiers, where we lived and worked. Several of the correspondents had just returned from the Tunisian front. An opportunity existed for some members of Stars and Stripes to be commissioned. One already had been James Burchard, a former sportswriter for the New York World-Telegram , who was in his late thirties (most of us were in our twenties).

Lieutenant Burchard and two sergeants described their reporting experiences. The lieutenant said that in order to get GI’s to speak to him freely he had to take his bars off and put them in his pocket; he did find the bars useful for eating and pulling rank for transportation.

As a result we decided to avoid commissions because correspondents could perform better as enlisted men. Most of us did not wear our sergeant’s stripes precisely because we wanted to foster the impression that we were—or at least until discovered—as privileged and possibly as talented as the regular civilian correspondents (whose pay greatly exceeded ours). I always liked to think of it this way: a Stars and Stripes reporter could honestly interview himself and, without fear of contradiction, say he had talked to a GI.

Although Stars and Stripes did have commissioned officers on the staff, they were mainly engaged in administrative duties. A specific difficulty arose when I was managing editor of the combined Oran-Casablanca edition of Stars and Stripes . A cast-off first lieutenant was assigned to us to censor the mail, requisition food, sign pay vouchers, and so on. He had been pressured by a base-section colonel to run that bane of all military newspapers, “The Chaplain’s Corner.” I refused

In nearly every other case involving this delicate issue of officer-and-enlisted-men relationships on Stars and Stripes , there was no awkwardness. Nearly everyone was on a first-name basis, regardless of rank. All of us were so pleased to be out of regular outfits that we gladly abandoned the normal military way.

Whenever another Mediterranean invasion was in the wind, everyone on the staff hoped to get a piece of the action. Stars and Stripes reporters were poised with different units before the invasion of Sicily, for example. Sergeant Ralph Martin went in with the Rangers; Sergeant Phil Stern, an ex-Ranger himself, took three hundred pictures with the Seventh Army; Sergeant Paul Green swept over the island in a 6-25; Sergeant Jack Foisie started out with the airborne infantry and, in the middle of the Sicilian campaign, was the only correspondent to accompany a small American force that made an amphibious attack seven miles behind the enemy lines along the coast of northern Sicily.

By the time the Mediterranean edition of Stars and Stripes had followed the troops across to Sicily and then to Naples and Rome, it had gained the loyalty and affection of officers and enlisted men—Air Force and Navy as well as Army. I saw its importance even to generals when American troops crossed the Arno and entered Pisa.

Naturally everyone wanted a close look at the leaning tower. I went there for a special reason; I was sure that the figures I had seen walking around its upper floors from across the Arno were German observers. I looked for a trace of their presence and found it in a piece of their orange-colored signal wire still hanging down. This, despite their claims that they were not using the campanile because it was church property. I was negotiating with an Italian official to enter the locked tower when, in a flurry of jeeps, General Mark W. Clark, the Fifth Army commander, drove up.

An affable general who was never shy about his personal publicity, Clark looked around for correspondents to cover him as he assumed the role of conqueror of Pisa. None had yet reached Pisa—except the correspondent from Stars and Stripes . The General cordially shook my hand and said, “Sergeant, why don’t we go up and take a look?” The General and I became the

Censorship and generals occasionally plagued Stars and Stripes. For the most part censorship was confined to military matters, such as making sure that fresh units were not identified until the enemy knew of their presence and strength. With this we, of course, did not disagree, since we were no more desirous of giving information to the Germans than was the censor. But when a story was held up for nonmilitary reasons, we complained.

I was impressed by the bravery, which almost reached the point of foolhardiness, of certain Italian partisans who were helping the Americans and British north of the Arno. When I wrote about them and their political radicalism, the story was stopped. I would resubmit it week after week, but that story never passed. On other occasions my colleagues and I learned how to circumvent censorship by planting in our copy certain obvious red flags that would be cut out in order to let other material stay in. These, in the main, centered on stories that revealed high-command clay feet.

While I was managing editor of the Sicilian edition of Stars and Stripes, probably the most sensitive story of the war fell into my lap. It was the incident in which General George S. Patton had slapped a hospitalized soldier. We knew about it, of course, but had a special problem (to put it mildly) in Sicily: General Patton and his Seventh Army headquarters were there. I had received a file of stories and matrixes from our weekly newspaper in North Africa and noticed that the Algiers edition had carried an AP story about the face-slapping incident. I thought this was the perfect solution. So I reprinted the wire-service story, put it under a fairly quiet two-column headline on the bottom of page i, and submitted it to the major from Army headquarters assigned as censor. He gulped, read the story, and smiled weakly.

“This story presents a problem,” he said. “Do you really want to run it?”

“Of course,” I replied. “All I’m doing is picking up the wire-service report that already appeared in Algiers.”

“But Patton is in Sicily,” he said, “and he reads Stars and Stripes every morning with his breakfast. Can you imagine him reading this?”

I could, but argued, “The integrity of the paper is at stake.

The major seemed to see the light—for a moment. “I’d better check this with the colonel,” he said. While I waited for my page proofs to be okayed, he called his next above. The major explained the story, then cupped the mouthpiece and whispered to me, “The colonel asked me to hang on while he checks with the General.” I whispered, ration: 1 he major nodded and said, (Jr Patton’s chief of staff.” Finally the voice came back on and the major signalled me to listen in with him.

“Major,” I heard the colonel say coldly, “the answer is, It’s your decision.” The major hesitated, and then said, “Can you give me some guidance, sir?” The colonel replied, “Major, I would suggest that you use your own judgment based on what is best for the Army.” He hung up. The major got the message. “My judgment is,” he told me, “you can’t run this story in Sicily.” As I picked up my page proofs and left without a word, he said, “Dammit, I’m sorry.”

Normally, being barless, stripeless, and in uniform had its advantages for the Stars and Stripes correspondent. The only instance in my own experience in which being an American soldier was the reason for not allowing me to cover a story occurred when the British reinvaded Greece in autumn of 1944. At the time I was covering Advanced Allied Force Headquarters (which wasn’t very advanced —it was in Rome; the regular AFHQ was still back at the palace in Caserta). From a friend on the British Eighth Army News , our allied opposite newspaper, I learned that some civilian correspondents were going to be allowed to accompany the British, but no American soldiers would be included. The given reason was that Greece was to be strictly a British “show,” on Prime Minister Churchill’s orders. No American uniforms were desired on the scene to complicate the future political leverage that the Churchill government wanted to exercise there alone. Months later we discovered that this part of the world was being made safe for the “democracy” of the restored Greek royal house.

When I requested permission to accompany the British and Parachute Brigade on the operation, I was politely refused. Then I heard that the U.S. 51st Wing would carry the chutists. I argued that they could not prevent me from covering just the American C-47’s taking part in the jump. A compromise was worked out: I would be allowed to go along but not to land in Greece. We took off from a base in southern Italy, flew across the Ionian Sea and along the Gulf of Corinth, and arrived in sunlight at the drop zone—a small airfield at Megara, west of Athens. Apparently the retreating

After interviewing people on the ground and getting such vitally unimportant information as the fact that most of the Greek partisans I spoke to seemed to have brothers who owned restaurants in the States, I wrote my stories. Later, at Advanced AFHQ , I had to honor my end of the bargain by such devious datelines as “With the 5ist Wing over Greece”—which, curiously, included talks with Athenians on the ground. More important than the stories, however, I brought back one of the ripped silk chutes to Rome, and a seamstress there made dozens of scarves for my Stars and Stripes colleagues to wear around their olive-drab throats that winter of 1944-45 m Italy.

Nearly all staffers had come to Stars and Stripes from other outfits by hook, crook, or luck. The Mediterranean edition had begun to publish in Algiers on December 9, 1942, a month after the North African landings. It had been preceded by a London edition—the first of World War II—that started on April 18, 1942.

The British edition was Air Corps oriented, because that was the only war they had to write about for more than two years, until the second front was opened in Normandy. Our edition was, from the beginning, infantry oriented. Not being stationed in England, we were also more politically aware around the Mediterranean, because our basic story was the rise of France overseas and the fall of Italian fascism. By the time we reached Rome we were putting out a newspaper that was superior to many dailies in the United States to this day. It was eight pages long; later, twenty-four on Sunday, including a magazine, a news review, and color comics—a mechanical achievement we were proud of. All of us spent many a Saturday night folding in the comics by hand for the Sunday paper.

We were lucky to have two unusual men to guide the VV Mediterranean edition administratively and editorially—Egbert White, who had been a private first class on the First World War Stars and Stripes and, after an advertising and publishing career, had entered the Army a second time; and Robert Neville, a journalist who had specialized in foreign news as editor and correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, Time magazine, and the adless newspaper, PM . In retrospect, what made them outstanding was that they not only knew their business but

Around the Mediterranean the editions included personnel from every department of a newspaper but the pressroom. We had our own photographers, engravers, linotypists, and make-ups. In the mechanical area the GI printers and specialists often worked side by side with French and Italian craftsmen, and there was great mutuality of interest. The administrative officers and editors worried about the paper from the time it was raw stock, shipped from the States, till it was printed and distributed. The paper’s circulation was handled by Sergeant William Estoff, who used everything from mules to C-47’s for deliveries. Outfits near the city where the paper was printed usually picked up their quotas with their own transportation. Our own Stars and Stripes trucks rode through the night to deliver the paper to front-line divisions north of Rome and Air Corps wings south of Naples. The paper cost two francs or two lire in rear areas but was distributed free at the front.

Some of the soldiers who applied for transfer to Stars and Stripes came right out of combat units during the Tunisian and Italian campaigns. In the case of the GI printers, Sergeant Irving Levinson, our mechanical superintendent, went looking for them, but it was usually the other way around for correspondents and editors. In either case the men knew what they were writing, editing, or printing, for they had been in line outfits themselves.

The way I joined Stars and Stripes was typically untypical. I had been in southern Algeria with an Air Corps wing. When time allowed I put out a mimeographed paper called The Bomb-Fighter Bulletin , its news literally pulled out of the air by monitoring the BBC and Radio Berlin. I accidentally saw a copy of Stars and Stripes and decided to apply for a job. With the help of a kind lieutenant from my unit who covered up for me, I went A. W. O. L. for two days and showed up in Algiers, where Stars and Stripes had its office. I was interviewed by Neville, then a harassed lieutenant, who moaned that he was having trouble finding solid newspapermen (which I certainly was not). Then he said, “Do you know that there are people on this paper who don’t know how to spell Hitler’s first name?” I trembled, fearing he might ask me, and I wouldn’t know whether he wanted it to end in f or ph . Fortunately he didn’t ask, and a

The story of how William Estoff, our circulation chief, got on Stars and Stripes was cherished by his friends as the definitive exposé of shavetails and military foul-ups. One day in England a call carne to a replacement depot for an enlisted man with newspaper circulation experience. A lieutenant dutifully examined the service records. He suddenly stopped at the name Estoff, private; age, mid-thirties; civilian occupation, bookmaker. (Estoff, a nightclub and newsstand operator, as a lark had listed himself as a bookie.) “Bookmaker,” the lieutenant is reported to have said. “That sounds close to what Stars and Stripes needs. Books—newspapers—can’t be too different.” Thus started a career for Sergeant Estoff’ that resulted in getting the ideal man for the complex assignment of making sure that the paper was circulated quickly to front-line divisions, plus the Air Corps and Navy.

As the war progressed, seasoned journalists—Hilary Lyons, Howard Taubman, John Radosta, John Willig, all past or future members of the New York Times —helped to turn the Mediterranean edition into a newspaper with a serious approach to U.S. and world events. Wire-service reports became available but were not accepted at face value. The major stories—our Italian front, northern Europe, the Russian counteroffensive, the Pacific theater—were handled on our own copy desk. The need was seen for better reporting from Washington and the home front slanted to an Army newspaper for men overseas, many of whom had missed three Christ mases home. One correspondent began to be rotated every four or five months; from where we sat in Algiers or Palermo or Rome, we referred to our man in New York as the “foreign correspondent in reverse.” Sergeant Bill Hogan was assigned to his home town, San Francisco, to report the founding of the United Nations there.

The Stars and Stripes in the Second World War leap-frogged the rear echelons. Thirty different editions were published; a number were dailies. Combined readership ran into the millions. As the Army freed each new island or town or country, editors, printers, and circulation men rushed into the nearest newspaper plant, occasionally at gunpoint, and took over. One of our lieutenants entered the plant of the Giornale di Sicilia , found the reluctant owner, and decided to put a fresh clip into his .45 at the moment of hesitancy. The owner relented, and Stars and Stripes began printing in Palermo. On the day Rome was freed, a dash was made for the plant of Il Messaggero by Sergeant Milton Lehman and several others, and a paper, headlined “ WE’RE IN ROME ,” was actually handed to some troops as they entered the city.

The news itself was supplemented by the two most popular features in the

The “Mail Call” column, edited by Sergeant Robert Wronker, exceeded the poetry in numbers received and printed. Initially, when Stars and Stripes published a new edition, the managing editor might write a few provoking letters under an assumed name to get the letters coming. What better way than to have a fictional “1st Sergeant McGonigle” demand more calisthenics for draftees overseas to keep them in trim as in the good old days of the prewar Regulars? What a private couldn’t tell his supply sergeant and what a platoon lieutenant couldn’t call a base-section saluting demon wound up in Stars and Stripes as a letter, poem, or article—and sometimes commanders listened, learned, restrained.

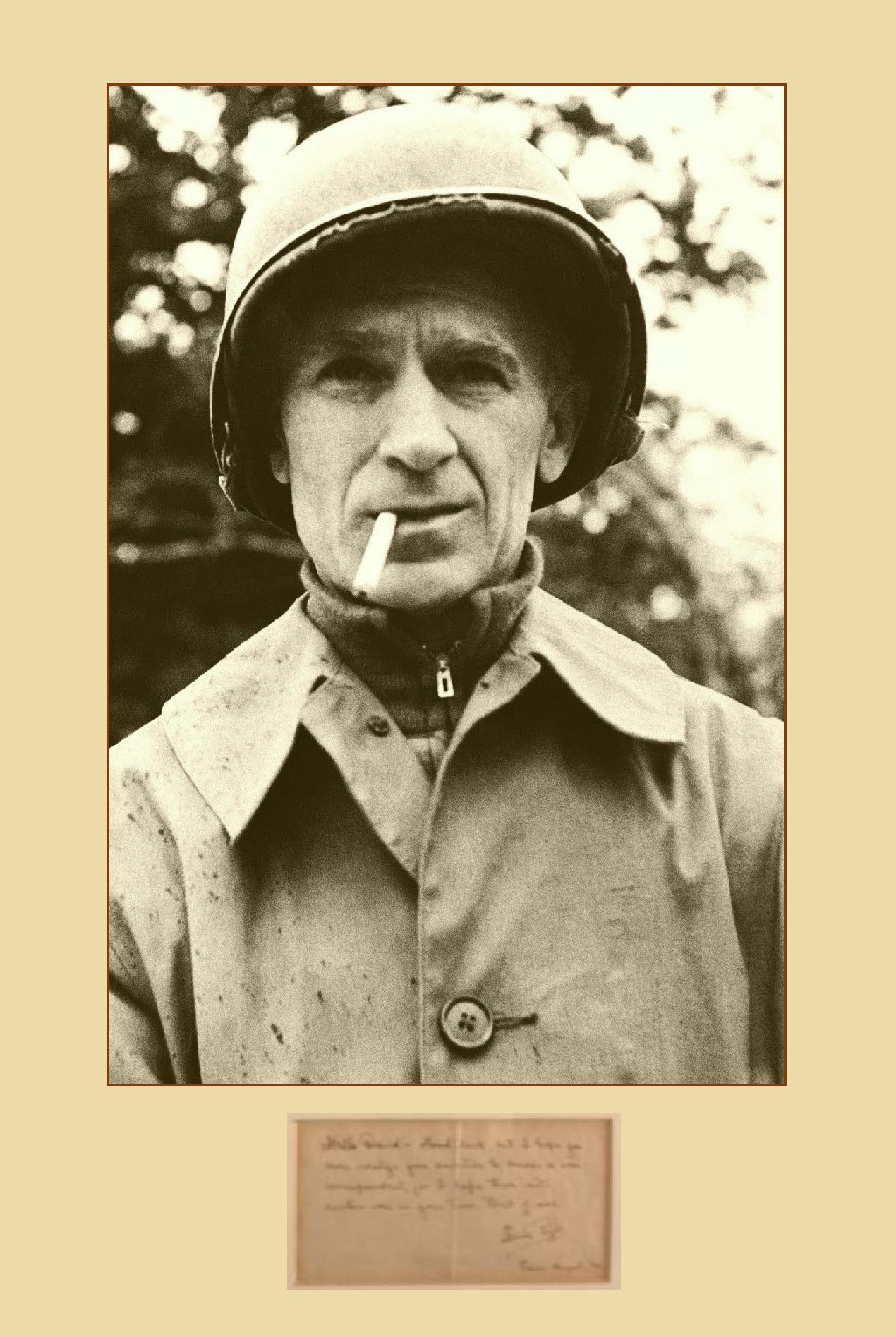

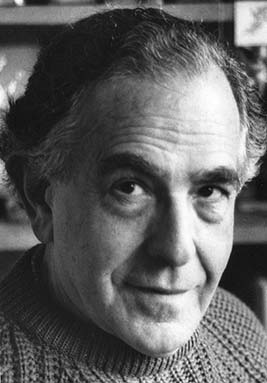

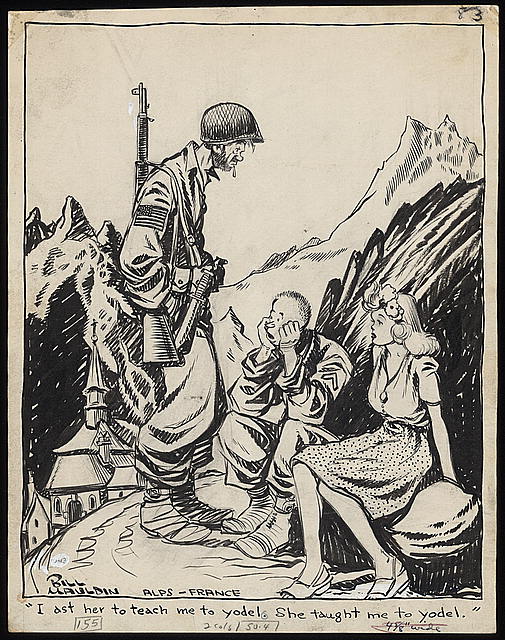

Bill Mauldin’s daily cartoon reflected the paper’s editorial attitude, yet he seldom editorialized. “Up Front … By Mauldin” was just that—a greatly talented soldier’s view of what was on the combat GI’s mind but not articulated until Mauldin expressed it for him in a simple sentence. He was in a direct line from the First World War’s Bruce Bairnsfather, the British creator of the “Old Bill” cartoons and the play The Better ’Ole . One of Mauldin’s early cartoons, showing the bearded Joe and Willie in an Italian foxhole, was captioned: “Th’ hell this ain’t th’ most important hole in th’world. I’m in it.” The Mauldin cartoons were not jokes; nor were they bitter humor. Rather, they were sardonic comments lifted out of the mouths and minds of front-line soldiers.

The cartoons invariably heroized the real dogface, often with a swipe at the rear echelon. In a cartoon that caused many soldiers to categorize themselves, Joe points to a couple of soldiers sitting at an outdoor café in France and comments, “We calls ‘em garritroopers. They’re too far forward to wear ties an’ too far back to git shot.” Mauldin’s cracks were against oppressive authority, officer or EM .

Most of the generals—with a notable exception—enjoyed the Mauldin cartoons, defended them, sometimes asked for an original. But

An obligatory scene was played out between the General and the sergeant at Third Army headquarters. Captain Harry Butcher, General Elsenhower’s naval aide, who arranged the confrontation, warned Mauldin to please wear a tidy uniform, stand at attention, and salute smartly. The General objected to the unkempt appearance of Willie and Joe; the sergeant said that he thought his characters faithfully represented the front-line GI . The meeting was a stand-off. Later, General Patton told Captain Butcher, “Why, if that little s.o.b. ever comes in the Third Army area again, I’ll throw him in jail.” Mauldin returned to Italy. Recalling the meeting long afterward, he told me, “I was frightened but steadfast.”

Occasionally, in Naples, Mauldin would try out one of his caption lines on me. Rarely did I succeed in getting him to change a word—for a very good reason: his ear had perfect GI pitch. Who could improve upon the cartoon showing two stuffy officers overlooking a sunset and its accompanying line: “Beautiful view. Is there one for the enlisted men?”

There was a special reason why formal editorials were not needed. A positive tone characterized the paper. Stars and Stripes was not an “Army” newspaper—it did not exist between the two World Wars—but, instead, a creation and expression of civilians under arms. A most important influence—more so than any general—was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who voiced the American dream in language understood by the ranks. The President’s popularity was shown by the soldiers’ ballots in the 1944 election.

The Four Freedoms speech delivered by Roosevelt, the inspiring speeches of Winston Churchill, the organization of the United Nations, were all fully reported in Stars and Stripes . The civilians in uniform who put it out had wide interests and horizons. We were, many of us, fresh from the New Deal years, and some of the sociological thinking for the little man (temporarily called the enlisted man) pervaded the reporting, not only of staff members but of letter writers and poets.

Stars and Stripes achieved a historical place because it was an altogether human paper; it became the printed record of the emotions and passions of its readers. Had it been up to some of the generals and commands, especially the base sections in the rear, Stars and Stripes would have been reduced to little more than an Army house organ. Some of the brass considered it only a training manual, publicity release, or hot potato, and seldom just a newspaper.

Whenever a particular command wanted to disavow disputes in the paper, they would issue an order making

From the Army’s point of view—except for the brief existence of Stars and Stripes in World War I—there was no tradition of untrammelled expression; indeed, that was the antithesis of military discipline and unquestioning conformity. The serious Stars and Stripes editors were always aware of this apparently irreconcilable conflict. Yet they strove to turn the paper into the voice of men—like themselves—temporarily in uniform, to deliver the news professionally and idealistically, to reflect ideas under stress and our postwar aspirations.

The Second World War multiplied battles and ideals all over the globe. By contrast, the Vietnam folly has diminished the United States in the eyes of even those peoples who once were freed by American soldiers. Correspondents and other observers caught up in wars past and present must still sit upon the ground and talk and write without sentiment of dictators and comrades; of the blacks and whites of conscience peering through the smoke; above all, of the need to escalate—in Asia and elsewhere—not the battles, but the ideals.

Stars and Stripes in the First World War was the famous one, and justly so. From February 8, 1918, to June 13, 1919, its staff in Paris put out seventy-one fiercely independent, sentimental weekly issues. It was run by enlisted men—Private Harold W. Ross, Railway Engineers; Private John T. Winterich, Aero Service; Private Hudson Hawley, Machine Gun Battalion; Sergeant Alexander Woollcott, Medical Department—who were the editorial Big Four. Two officers—Captain Franklin P. Adams and Lieutenant Grantland Rice—for a time served as columnists. Many future journalists of distinction rounded out this brilliant staff, and outside poetry contributors included Sergeant Joyce Kilmer.

The formal authorization came in a message from General John J. Pershing that appeared on the first page of Volume 1, Number 1: “In this initial number of The Stars and Stripes, published by the men of the Overseas Command, the Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces extends his greetings through the editing staff to the readers from the front line trenches to the base ports. … The paper, written by the men in the service, should speak the thoughts of the new American Army and the American people from

It was only in the years after World War II that historical research uncovered casual editions of Stars and Stripes that existed even before the famous World War I edition. The first issue of the Stars and Stripes as a military paper appeared in Bloomfield, Missouri, on Saturday, November 9, 1861. This edition was published by Union soldiers of the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteer regiments. Unfortunately the paper only appeared once, probably due to the exigencies of the war in the Union’s Department of the West.

Other issues of soldier papers called Stars and Stripes were put out by men in blue during the Civil War. Each one was independent, and no links existed between these short-lived issues and Washington. A group of federal privates held in Confederate prisons in Richmond, Tuscaloosa, New Orleans, and Salisbury, North Carolina, for ten months before being exchanged in 1862 produced a hand-written Stars and Stripes . One of the offices where the paper was written was “Cell No. 9, third floor.” Other independent editions of Stars and Stripes appeared in Jacksonport, Arkansas (the editor was post surgeon of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment of Missouri Volunteers), and in Thibodaux, Louisiana, in the local office of the Thibodaux Banner (whose owner had departed hurriedly) by Connecticut’s 12th Regiment. Both editions were printed on wallpaper due to the shortage of newsprint.

On the Confederate side of the lines, peripatetic-soldier papers were published, too. One was called the Daily Rebel Banner, but there was no Stars and Stripes .