Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1975 | Volume 27, Issue 1

Authors: Scarritt Adams

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1975 | Volume 27, Issue 1

It was obvious that something very special was needed to confront the ironclad that the Confederacy was furiously building if the Union was to be saved. Yet it took a personal visit of Abraham Lincoln to the somnolent offices of the Navy Department to force the issue, and by then it was so late that the Navy Department had to have a miracle. In short, the contractor would have to build, in a hundred days, a kind of ship that had never been built before, and build it in a desperate race against time.

To sign a contract calling for a miracle in a hundred days was all very well, but there had to be a miracle man to do it. There was probably only one man in the world who could. He was John Ericsson, the great inventor.

Whether Ericsson would was another matter. He had become decidedly unenthusiastic about doing business with governments. Napoleon III had turned down his plans for a ship with a movable turret—what Ericsson called a monitor. The British Admiralty had refused him payment for his unique screw propeller on the ground that a rival inventor had already patented one. Ericsson’s screw propeller had been demonstrated on a vessel built in England in 1839 and named after his friend Captain Robert F. Stockton of the United States Navy. And it was at Stockton’s urging that Ericsson subsequently came to the United States and put one of his propellers on the u.s.s. Princeton , the first warship in the world to have one. Unfortunately, during a demonstration firing, the Princeton ’s big twelve-inch experimental gun exploded, killing Secretary of State Able P. Upshur, Secretary of the Navy Thomas W. Gilmer, and four other persons. Stockton, the skipper of the Princeton , turned on his friend Ericsson and made him the scapegoat of the tragedy. In consequence Ericsson vowed never again to deal with Washington, and Stockton continuously opposed the inventor’s enterprises. His would be the hidden voice of a widespread navy coterie in 1861 that was against any such nonsense as what was variously called “Ericsson’s Folly,” a stupid “cheesebox on a raft,” a silly “tin can on a shingle.”

That first summer of the Civil War was an especially fretful one for Navy Department officials in Washington. Lincoln had proclaimed a blockade of all southern ports, but the Navy was seriously hampered by the lack of ships

The newfangled ship all covered with iron plates being built by the Confederates was the powerful steam frigate Merrimack , burned and scuttled by Union forces when they evacuated Norfolk. The rebels had raised her and were busy refitting her into an ironclad ram that they rechristened the Virginia . (The vessel’s name has nevertheless come down in history in the Union version, minus the k .) The Confederates were improvising what looked like a floating barn roof with ports for ten guns. The hull was being cut down to the water line, a long iron-plated superstructure was to be placed on top, and a four-foot cast-iron prow affixed to her bow.

Lincoln had appointed Hiram Paulding, an aged hero of the War of 1812, to “put the Navy afloat.” Paulding naturally called into consultation the chief of the Bureau of Construction for the Navy, old John Lenthal. Lenthal would have no truck with such nonsense, remarking that building ironclads “was not his trade” he remained silent thereafter.

At last Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, sent a message to the special session of Congress meeting on the Fourth of July, 1861, suggesting that a special board be appointed to investigate the feasibility of building one or more ironclad steamers or floating batteries. Congress complied, authorizing the expenditure of $1,500,000 for construction if the board reported favorably.

Then the contractors entered the picture like hawks. The iron interests went to work. Cornelius Bushnell, president of the New Haven, Hartford and Stonington Railroad, one of the foremost of the lobbyists, persuaded the chairman of the Naval Committee to get behind the Ironclad Bill and push it through the House. The Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen R. Mallory, had already issued orders on July 11 “to proceed with all possible despatch” with the Merrimac ’s rebuilding; it was obvious to all that time was essential.

On August 3 Congress approved the bill and authorized the Secretary of the Navy to appoint a board of “three skilful officers” to look into the matter. Four days later the Navy Department, now moving at unprecedented speed, in a “public appeal to the mechanical

The iron interests and the ship-builders of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia were in a frenzy of activity. By the deadline sixteen companies had submitted proposals to the Ironclad Board. E. S. Renwick of New York proposed a 6,250-ton giant, 400 feet long, that would speed along at a phenomenal 18 knots and cost $1,500,000. Donald McKay, famed builder of the world’s fastest clipper ships, wanted to spend $1,000,000 on his version and take nine months doing it. Cornelius Bushnell submitted plans for still another ship, the Galena .

John Ericsson was not among the sixteen entrants. One day, however, when Bushnell returned to Willard’s Hotel, where he was staying in Washington, he ran into Cornelius DeLamater, a well-known and highly respected machinist. DeLamater was a friend of Ericsson’s; indeed, the two had become close associates soon after first meeting in 1839, when Ericsson arrived in the United States. DeLamater’s father had bought into, and eventually took over entirely, an ironworks foundry in lower Manhattan, and Ericsson in 1844 had taken up quarters nearby, at 95 Franklin Street.

Bushnell told DeLamater about the plans for the Galena that he had submitted to the board; DeLamater suggested that it would be a good idea to check them with Ericsson. Bushnell agreed and took a train to New York.

When Ann, the elderly maid, opened the door at 95 Franklin Street, Bushnell found Ericsson sitting on a revolving piano stool in a combined bedroom-workroom. Bushnell offered to show him the Galena plans. Ericsson consented, and the next day, when Bushnell returned, the inventor assured him that they were all right and asked if Bushnell, by the way, would like to see some old plans and a pasteboard model he had of a floating battery, a turreted ironclad with two big guns mounted in a revolving roundhouse. Opening up a dusty box, Ericsson laid open the plans shown to Napoleon in in 1858. Bushnell was impressed, so much so that he took them then and there and rushed off to show them to Gideon Welles, who was visiting in Hartford. The Secretary was equally impressed. He advised Bushnell to take the plans to

As soon as Bushnell got back to Washington, he looked up two business associates, John A. Griswold, president of the Troy City Bank, and John F. Winslow, a Troy iron-plate manufacturer. Bushnell offered them a quarter interest each in the floating battery if he was awarded the contract. Unable to impress Commodore Joseph Smith of the Naval Board, he got a letter of introduction from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Lincoln, the one man in Washington who could get things done. The three businessmen presented their case to the President, who said: “I don’t know much about boats but … I will meet you tomorrow at 11 a.m. in Commodore Smith’s office and we will talk it over.”

The members of the Ironclad Board were Commodores Smith and Hiram Paulding, both born in George Washington’s time, and Commander Charles H. Davis. They all had a reputation for being extremely cautious and critical. Paulding had already confided to his wife that “ironclads will be more tedious than I thought.” Nevertheless he would be inextricably involved in the fortunes of the Monitor—as Ericsson later officially named his vessel—not only as a member of the Ironclad Board but later as commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where it would be his duty to outfit her and send her off to do battle. Smith, who would have more to do with the Monitor than anybody else, was chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks. His reputation for safeguarding the interests of the Navy was such that it was said he always “seemed to sleep with one eye open.” Although Smith admired Ericsson, the validity of the plan for a floating battery would have to be very convincingly demonstrated. Davis, the junior member, was dead set against it. With his skill at debate he would be a dangerous opponent. These, then, were the men Bushnell’s party would have to persuade.

At the appointed time the President turned up in Smith’s office. So did Gustavus Vasa Fox, the dynamic new —and first—Assistant Secretary of the Navy, lobbyist Bushnell, banker Griswold, iron man Winslow, Commodore Paulding, and Commander Davis. Nearly everybody admitted Ericsson’s plan was novel. But Davis thought it was silly and ridiculed it. Smith was noncommittal. Lincoln listened for an hour and then in closing the meeting remarked: “All I can say is what the girl said when she put her foot in the stocking: ‘I think there’s something in it.’” Thus Ericsson’s Floating Battery became the seventeenth entry.

The Ironclad Board finished its meetings on September 16. Its formal report turned down fourteen of the seventeen proposals. McKay’s proposal was rejected because his ship was too slow. Renwick’s eighteen-knot giant cost too much; it would eat up the entire appropriation. But

However, when Smith reconvened the board the next day, Davis prevailed and Ericsson’s plan was rejected. It seemed that there would be no Monitor .

Lobbyist Bushnell thereupon got to work on the members of the board individually. As a result Paulding and Smith promised they would vote approval if Bushnell could get Davis to go along with them. So Bushnell tackled Davis, a hard nut to crack. Davis was still adamant and told Bushnell that he “might take the little model home and worship it, as it would not be idolatry, because it was made in the image of nothing in heaven above, or the earth below, or in the waters under the earth.” There was only one thing left for Bushnell to do. That was to bring Ericsson to Washington to confront Davis in person. Accordingly Bushnell went off to New York, and Commodore Smith helped out by writing to Ericsson that there “seemed to be some deficiencies in the specifications,” that “some changes may be suggested,” and that “a guarantee would be required.”

Convinced by Bushnell that Davis merely wanted a few points about his plan clarified, Ericsson took a train for Washington and on meeting Davis declared: “I have come down at the suggestion of Captain Bushnell, to explain about the plan of the Monitor .”

“What,” queried Davis, “the little plan Bushnell had here Tuesday; Why, we rejected it in toto .”

“Rejected it! What for …?”

“For want of stability. …”

“Stability,” exclaimed the amazed Ericsson. “No craft that ever floated was more stable than she would be; that is one of her great merits.”

Davis, softening, answered: “Prove it … and we will recommend it at once.”

“I will go to my hotel and prepare the proof … and meet your Board at the Secretary’s room at 1 o’clock.”

In a two-hour presentation Ericsson proved the stability was satisfactory beyond a doubt. After he withdrew, the board deliberated for two more hours, at the end of which they notified Gideon Welles that they were satisfied. Welles called Ericsson to his office late that afternoon and in a five-minute interview told him to get started immediately. The contract could be signed later. Ericsson rushed back to New York to get to work.

Griswold and Winslow now began looking for someone to build the Monitor. They got on a ferry in lower Manhattan and crossed the East River to the heart of the Greenpoint shipbuilding industry. At a plant named the Continental Iron Works they met bearded, thirty-year-old Thomas Fitch Rowland, the proprietor. Griswold and Winslow asked him how much a pound he would charge to make an iron

On October 4 the government contract with Ericsson and his associates was drawn up and signed. It said: “It is further agreed between the said parties that said vessel and equipment in all respects shall be completed and ready for sea in one hundred days from the date of this indenture.” In addition, a “small-print” clause stated that if the vessel—“an Iron-Clad-Shot-Proof Steam Battery of iron and wood”—was not a success, the party of the first part would have to refund to the government all moneys received.

On the day the contract was signed, Bushnell drove home to Commodore Smith what a good bargain he was getting. “The whole vessel with her equipment,” he said, “will cost no more than to maintain one regiment in the field 12 months … should [it] prove what we warrant it, will it not be of infinitely more service than 100 regiments?”

Bargain or not, time was still the crucial factor: the Merrimac , being constructed in Norfolk, already had her hull, boilers, and engines completed, though the iron sheathing for her sloping deckhouse was not yet ready.

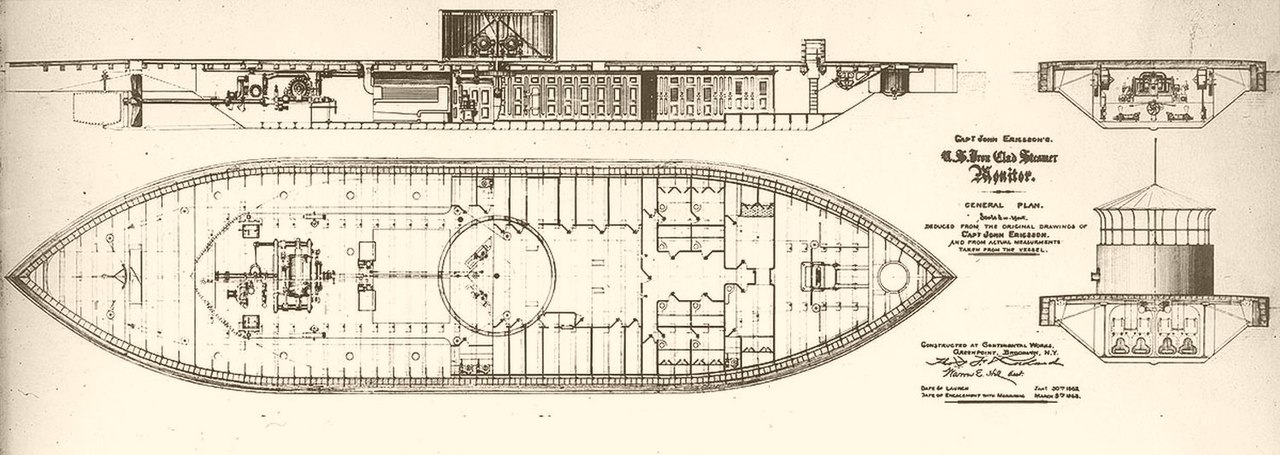

The party of the first part organized to accomplish the impossible. They had to mobilize capital, planners, manufacturers, and shipbuilders into a close-knit, fast-working team. The nerve center would be Ericsson’s room on Franklin Street. Griswold, tycoon of Bessemer-process iron, would handle the finances, making all payments. Rowland would build the hull. The revolving turret, the truly unusual feature of the whole project, would be fabricated, appropriately, at the Novelty Iron Works of New York. Machinery, boiler, and turret-turning apparatus would be made in the DeLamater Iron Works. The iron plates would be rolled out by the Albany Iron Works in Troy. The gunport shields fon the turret were to be made by Charles D. Delaney in Buffalo.

Winslow would be the expediter for materials shipped out of Albany. “One hundred days, and they are short ones, are few enough to do all that is to be done,” he declared. He wanted the hull-plate specifications immediately because “the making of slabs is the longest part of the operation.” On October 12, only eight days after the contract was signed in Washington, Winslow wrote Ericsson: “I am now able to say that every bar of angle iron is now made and ready to go on board of Monday’s steamer and be in New York on Tuesday morning. On Tuesday another lot will follow and so on daily until the entire order for hull plates is

Meanwhile Rowland had readied the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint. Its many buildings sprawled over a large city block from the East River inland. He built a ship house over the building ways large enough to accommodate Monitor ’s 172-foot-long, 41-foot-wide armored raft and the supporting hull proper.

Rowland made a model of the ship, showing how the armored raft considerably projected over the 124-foot by 34-foot iron hull that supported it. By fitting patterns on the model he determined the exact size of the armor plates needed. He numbered these in sequence so that when the fabricated ones arrived from Troy they could be accurately put together without time-wasting refitting. By October 19 he had submitted his estimate for the woodwork—oak beams, white pine, and oakum, 7,000 spikes, bolts two feet long, millwork, and carpenters’ labor, all totalling $11,287 net.

On October 25 Rowland laid the keel. And at long last he also received a formal contract from Ericsson and his associates. By its terms he promised to do the work “in a thorough and workmanlike manner, and to the entire satisfaction of Captain Ericsson, in the shortest possible space of time” and “to launch said battery safely and at his own risk and cost….” Ericsson in turn promised to furnish all the material, pay for the ship house, and pay for constructing the hull at the rate of 7½ cents for each pound of iron used. The furnaces of the Continental Iron Works were fired up.

Ericsson was a demon. He planned and drew and superintended incessantly. Daily he took the ferry over to the shipyard. He climbed all over the building ways, observing everything with a keen and critical eye. In the early morning and late evening he drafted the hundreds of detailed plans at his office. The blueprints flowed directly from him to the various shops, and as soon as the material arrived, each piece was manufactured immediately. If it wasn’t right, he was there to adjust it. He made his designs of the utmost possible simplicity in order to speed up the work. “The magnitude of the work I have to do,” he said, “exceeds anything I have ever before undertaken.”

Commodore Smith was right on top of him. Before the keel was laid, Smith was already worrying about the ventilation, writing on his lined blue notepaper that “sailors do not fancy living under water without breathing in sunshine occasionally.” And what’s more, he didn’t like the plan for the rudder. Ericsson wrote back consolingly: “I beg you to rest tranquil as to the result; success cannot fail to crown the undertaking.” But when, the day after the keel was laid, Smith wanted to know how a man five feet eight inches tall could stand in a five-foothigh pilothouse, Ericsson’s reply was not altogether satisfactory: “It is

At the DeLamater Iron Works, Cornelius DeLamater went about manufacturing the machinery for the turret-turning device and the main propulsion plant, the boilers and the propeller. “The motive engine,” said Ericsson, “is somewhat peculiar, consisting of only one steam cylinder with pistons at opposite ends, a steam tight partition being introduced in the middle. The propeller shaft has only one crank and one crank pin.”

Even if it did get made right, and in time, who was going to be smart enough to operate it on board ship? Ericsson was worried about this. He wanted an engineer named Alban C. Stimers, who he thought was the only one in the country for the job. By an odd chance, Stimers had been chief engineer of the Merrimac two years before. Ericsson asked for him, and Commodore Smith wrote that Stimers would be there in a week. By then it was November.

The turret was meanwhile shaping up at the Novelty Iron Works, directly across Manhattan from DeLamater’s plant. It was a monstrous thing, twenty feet in diameter, nine feet high, and with sides eight inches thick, made of eight layers of plate. It was shotproof. The job required an industrial plant capable of the heaviest kind of work. The ironworks’ title, sounding more like a ladies’ notion store, hardly suggested anything more substantial than a safety pin. Yet it was a massive iron foundry. Its main building was 206 feet long and 80 feet wide, housing four cupola furnaces and six drying ovens. The world’s largest steam cylinder, for the Fall River Line’s Metropolis , had been built there. (The cylinder was so big that twenty-two people had once sat down to lunch in it.)

Smith wanted to know from Ericsson “more than the specifications state, your plan of putting the turret together.” It was hard enough as it was without the commodore’s nagging. They were having a tough time making room in the turret for the crew and especially for the recoil of the eleveninch guns. “I must insist,” said Smith, “on the guns having the full length of recoil.” Engineer Stimers, now on the scene, said the guns would have to be shortened at least eighteen inches to work in the turret. No, said Smith. The eleven-inch Dahlgren guns “are the guns I intended for it and none others are to be had.” The great gunmaker Admiral John Dahlgren reported from the gun factory in Washington that if eighteen inches were cut off the guns, they would lose 50 per cent of their effectiveness. So Novelty Iron Works forged ahead, building the tracks in the turret for the two gun carriages. While all this was going on in New York, Delaney, in Buffalo, made the gunport shields for the turret so that they would swing, pendulumlike, to close the ports when the guns were retracted into the turret

By now it was November 18, and Smith wrote tartly: “I received the copies of the Scientific American and regret to see a description of the vessel in print before she shall have been tested.” Obviously, the Confederate government would now be alerted to the urgency for launching the rebuilt Merrimac .

By Thanksgiving the government made its first payment—a draft on the Navy Agent in New York for $37,5oo. In the meanwhile banker Griswold had been making weekly cash payments to all the subcontractors for work performed to date.

During December the work moved on steadily, with much less bickering from Washington and a payment of fifty thousand dollars more. The Secretary of the Navy, in his annual report on December 2, said the Ironclad Board had “displayed great practical wisdom” in this new branch of naval architecture. But Smith was not relaxing one bit. He sent a terse warning to Ericsson on December 5 to “push up the work … only thirty-nine days left.” A week later he feared that the beams under the battery were too small.

At the Continental Iron Works, Rowland’s men bolted on the side and deck armor amid rumors that spies had gotten into the shipyard and were passing along a flow of information to Richmond.

Christmas came and went. On December 30, in his Manhattan shops, Cornelius DeLamater turned on the steam to test the forty-inch cylinder. The slide valves opened and admitted steam, and the great piston moved full stroke and back again. The Monitor ’s engineering plant was all right. It was loaded in sections onto barges and lightered around the Battery, up the East River to the Continental Iron Works. DeLamater’s men followed and began installing it. There was barely room for the boilers, cylinder, and large steam pipes in the eleven feet six inches between bottom and deck.

January of 1862 was the critical month. The contract time would expire; she would have to be launched. Yet the gun problem had not yet been solved. The Brooklyn Navy Yard, where the Monitor would have to be fitted out, was having strike trouble. New Year’s Day started out with a fierce gale that tore the North Carolina , then training the Monitor ’s crew, away from her pier in the Navy Yard and bashed her stern in.

It was a cold winter. To the touch, iron had the sticky feeling of quickfreezing. The first week of the new-year was hardly out before drifting ice filled up the East River, blocked the Brooklyn waterfront, and backed up into Bushwick Creek bordering on the Continental Iron Works. Three days before launching, outside work in shipyards had to be suspended on account of stormy weather.

On January 14 Commodore Smith wrote Ericsson a nasty note on his blue paper, reminding him that

At Novelty a barge was warped under the company’s huge forty-ton crane, a landmark towering over its private pier. Sections of the enormous turret were lowered on board, and the barge was towed to the Continental Iron Works. The turret sections were taken into the ship house, placed on the Monitor , and assembled. DeLamater’s men connected its double train of cogwheels with the small steam engine that would turn it. This completed Monitor ’s well-known “tin can on a shingle” silhouette.

Practical details were now worked out. The ship, up until this time really nameless, was usually referred to as Ericsson’s Battery. Ericsson now proposed to the Navy the name Monitor . Twenty-two-year-old Lieutenant S. Dana Greene, the officer who would ride her down the ways on launching, was assigned as executive officer. Rowland prepared for the launching, asked Ericsson to send riggers to assist, and constructed wooden boxes to buoy up the ship’s stern lest she plow too deep in the water upon leaving the launching ways.

Smith forwarded the news that the Merrimac had been floated out of dry dock on January 25 and urged Ericsson to hold the Monitor ’s trials as soon as possible.

With some fanfare the Monitor moved out of her ship house at 9:45 A.M. on January 30, gathered momentum, and slipped down the inclined ways into the cold waters of the East River, buoyed up by the wooden boxes. The Stars and Stripes flew from the turret and flagstaff. Steam tugs, puffing black smoke and white steam, stood by to help. Ericsson, in company with Lieutenant Greene and Acting Volunteer Master L. N. Stodder, stood on her decks while a top-hatted crowd watched from the ship house and the shores of the river. It was the hundredfirst working day from the date the contract was signed and the hundredth day from the laying of the keel.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of January 31 reported:

The launch of the iron-clad battery Ericsson took place yesterday at Rowland’s Shipyard, and was highly successful. The vessel is broad and flat-bottomed, with vertical sides and pointed ends, requiring but a very small low depth of water to float in, though heavily loaded with an impregnable armor upon its sides and a bomb-proof deck, on which

Gustavus Fox sent Ericsson a telegram on the launching day to “hurry her to sea as the Merrimac is nearly ready at Norfolk.”

Things were moving. The Monitor needed only guns, crew, and trials and she would be ready. On the day she was launched, the ordnance officer at the Brooklyn Navy Yard told Ericsson he had been authorized to take two eleven-inch guns out of the gunboat Dacotah for the Monitor , so “if you will send your derricks to the yard the guns can be hoisted out.” Ericsson wrote Smith that the Monitor was nearing completion, which pleased the old man greatly. “She is much needed now,” he replied.

Now it was February. The East River froze over. By the third, Fox had wired Ericsson again that Lincoln wanted to know when the Monitor would be ready. Trial time was at hand. On February 5 the two Dahlgren guns were mounted in the turret, “presenting a formidable appearance.” On the ninth the main engine was turned over, and the ventilation, on which so much depended, was tested. On the eleventh Paulding wired Washington that she would be ready in a week, but the blacksmith shop in the yard blew up, and Ericsson was having trouble with the turret-turning gear, the piston valves being “too snug.”

At last, on February 19, DeLamater’s mechanics lighted the fires in the boilers and warmed up the engines. Ericsson boarded the Monitor , and she headed out into the river for her first trial trip, in a blinding snowstorm driven by a northeast wind. DeLamater’s men soon began having trouble. The little cut-off valves that controlled the admission of steam to the cylinder had unfortunately been put on backward; the vessel could not get up to speed. The valves were adjusted, and that same evening, as the snow changed to a torrential downpour of rain, Thomas Rowland delivered the Monitor to Hiram Paulding at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for fitting out.

Down south in Hampton Roads, Commodore Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, had a motley array of vessels—old sailing frigates, steamers, and tugs. They were all in danger. The Merrimac could sink them at will and, it was feared, proceed north and burn out New York Harbor. Would the Monitor never get there?

Washington was in a frenzy. On February 20, the day the

The next day a messenger from the American Telegraph Company sped to Ericsson’s office on Franklin Street. He bore an envelope directed to “J. Ericsson, Constructor of Iron Battery.” Opening it, Ericsson read: It is very important that you should say exactly the day the Monitor can be at Hampton Roads. Consult with Comdr. Paulding.

G. V. FOX¥¥ Ass’t Sec’y Navy

Three days later Griswold, running the Monitor ’s finances in Troy, wrote hoping that she would be ready in time to stop the Merrimac . A northwest gale, so violent that the cupola of the Brooklyn City Hall “occilated like a pendulum,” raged in New York Harbor, damaging many vessels. Fortunately the Monitor did not suffer. A new underwater cable from Fortress Monroe to Cape Charles was completed, and news of Confederate doings would get north twelve to twenty hours sooner. Rebel Secretary Mallory finally got around to ordering a commanding officer for the Merrimac , old disciplinarian Captain Franklin Buchanan, who had been the first superintendent of the Naval Academy at Annapolis and at the time the war broke out had commanded the Washington Navy Yard. But the Merrimac still had not been loaded with ammunition for her guns.

On February 25 the Monitor was officially commissioned at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The crew marched over from the North Carolina and skidded down the gangway sloping steeply from the pier above to the iron deck of their strange new ship, which floated barely eighteen inches above the river. They could lean over and put their hands in the water. All they saw on her bare decks were the turret, the tiny pilothouse near the bow, and the two small ventilator cowls at the other end. Captain Worden ordered the flag run up. He read his orders and broke his commission pennant. She was at last a ship of the United States Navy. The watch was set and her log started. The new crew loaded on stores, provisions, and ammunition. Ericsson telegraphed Gustavus Fox that the Monitor would indeed leave on the morrow.

And so the Monitor departed on the morning of February

Her return caused dismay. Rowland said he could put the Monitor in the sectional dock at the foot of Pike Street “with perfect safety, alter her rudder, and have her out in 24 hours.” But Ericsson, greatly annoyed, said it was entirely unnecessary to dock the ship, and in fact he made the adjustment without docking her.

At the same time Flag Officer French Forrest, commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, was getting desperate for gunpowder for the Merrimac . He needed it at once. It would take three full days to fill the Merrimac ’s cartridge boxes, and it was already February 28.

On March 3 Winslow was writing Ericsson from Troy, supposing the Monitor was “ere this en route to Hampton Roads.” But she wasn’t until the following day, a blustery, cold March 4. A board of experts went on board the Monitor . Captain Worden took her out into the open sea off Sandy Hook for her final checkup. The two eleven-inch Dahlgrens were loaded with fifteen-pound powder charges and solid shot weighing 168 pounds. The pendulumlike gunport shields were swung aside. The gun carriages ran out on their rails until the gun muzzles protruded outside their gunports. They were fired time and again. The new turning mechanism, which had caused Ericsson so much trouble, swung the twenty-foot turret around smoothly. Even the bothersome steering gear worked. The trial was a success, and the board of experts gave the Monitor its approval. She returned triumphantly to the yard at five o’clock that evening. Commodore Smith was pleased enough to send a draft for $18,750. But there still was a great deal of work to do. Sailing date was fixed for March 6. Nevertheless Lieutenant Greene, her executive officer, the man who should have known, did not see how they could possibly make it.

Paulding ordered the steamers Currituck and Sachem to stand by to escort the Monitor to Hampton Roads and a tug to take her in tow. It would be a wild trip in the rampaging winter Atlantic. Even Captain Worden thought she might capsize in case of heavy gales.

At about 11

Friday March 7 was an angry day at sea. Dreadful things happened on board the Monitor . Water poured down through the turret foundations and into the boiler room, unchecked by the makeshift oakum packing that had been added without Ericsson’s knowledge. The blowers quit. Men in the engine room nearly suffocated and had to be dragged out. The engine stopped. The captain ordered the tug to tow her inshore close to the coast, where there would be calmer water. Five hours were lost. At Norfolk, that Friday was a trying day for the Confederacy too. Although the Stars and Bars were run up on the Merrimac , her crew was worried. All her officers knew that the ship was not prepared for the heavy work she had to do. Her engines had not been tested. Her water line was her weak part, her Achilles’ heel. A well-directed fire here, and she would be done for. Some crew members predicted total failure; few expected to return to Norfolk. Yard workers swarmed all over the ship in a last-minute effort to finish the work. That evening the Monitor got going again. Chief engineer Alban Stimers, despite the discouragement of all hands, insisted that they keep on. Captain Worden kept the deck all night in the tiny pilothouse. The whole crew was already exhausted, choked with fumes and water-soaked. But the Monitor steamed steadily on. It was Saturday morning, March 8. Commodore Goldsborough’s blockade squadron rode at anchor in Hampton Roads, engaged in dull routine. He had waited so long for the Merrimac , had heard so many cries of wolf, that now on this pleasant day he was lulled into a false sense of security. It was a lovely morning with hardly a ripple on the surface of the bay. Over at Newport News the old fifty-gun frigate Congress , commanded by Joseph B. Smith, the commodore’s son, waited. Nearby was the Cumberland , while over by Old Point Comfort the remainder of the squadron, headed by Van Brunt’s steam frigate Minnesota , was disposed. Gustavus Fox left Washington and went down to Fortress Monroe, guarding Hampton Roads, to see how the Monitor would make out. Just before 11 A.M. the Merrimac ’s quick-tempered skipper—hopelessly suffering, said a doctor, from “nervous prostration”—ordered her to sail. She moved out from the pier with

The U.S.S. Cumberland sent the tug Zouave to Pig Point to reconnoiter—to see what all that smoke was coming down the Elizabeth River. After a bit the officers of the Zouave saw “what looked to them like the roof of a barn belching forth smoke from a chimney.” It was the Merrimac . No real worry, though. She was hugging the opposite shore so closely and moving so slowly that obviously she was on no more than a trial run. At about 4 P.M. the Monitor passed Cape Henry and entered the Chesapeake. Her crew heard what sounded like gunfire. It was in fact the Merrimac in the act of destroying the Congress, whose captain, young Joe Smith, was killed. A pilot came on board the Monitor and told about the havoc the Merrimac had created in the Union squadron. The Minneapolis was aground, the Congress on fire, and the Cumberland sunk in fifty-four feet of water. The Monitor rushed ahead to the battle area, but it was too late. The victorious Merrimac had already retired for the night. So the Monitor anchored alongside the Minnesota and waited for the dawn. By 8 P.M. the Merrimac was anchored off Sewall’s Point. She had lost her prow but was otherwise in fighting trim. Her exhausted crew had to clear away the debris of battle before the cooks could get supper ready at eleven o’clock. After supper the men stayed up to watch the fire they had started over by Newport News. Shortly after midnight the Congress blew up. It was not until then that the crew of the Merrimac, satisfied, turned in. But they were soon up again, and her anchor was aweigh at 6:20 A.M. One hundred minutes or so later the Monitor and the Merrimac met in the momentous first battle between ironclads. The Merrimac, accompanied by several steamers, headed directly toward the Minnesota, firing at the Union vessel, which had been run aground the previous day. Aboard the Monitor Captain Worden gave the order to commence firing, with young

The grueling four-and-a-half hour battle had ended in a stand-off, but for all intents it was a Union victory. As Gideon Welles put it: There is no reason to believe that any of our wooden vessels guarding the Southern Coast would have withstood her [the Merrimac’s] attacks any better than the Cumberland, Congress, or Minnesota. She might have ascended the Potomac, and thrown bombshells into the Capitol of the Union. In short it is difficult to assign limits to her destructive power. But for the timely arrival of the Monitor … our whole fleet of wooden ships, and probably the whole sea coast, would have been at the mercy of a terrible assailant. Though a return engagement was expected, none took place, and when in May the Confederates evacuated Norfolk, they decided the Merrimac was too unseaworthy for the open ocean and drew too much water to make it up the James River to Richmond, so her own crew destroyed her. The Monitor , with young Greene still aboard, was being towed to blockade duty off Beaufort, North Carolina, when she foundered off Cape Hatteras during a storm at sea on December 31, 1862. John Ericsson continued to build ironclads for the Union navy for the remainder of the war; but the building of the unique Monitor had made him a hero—the hero of the “hundred-day miracle.” The Monitor was not officially declared “out of commission” by the Navy until September 30, 1953. Twenty years later—in the summer of 1973—a team of oceanographie researchers from Duke University discovered her remains lying in 220 feet of water about fifteen miles south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, where she had gone down in 1862. The find was verified through the use of underwater television cameras, sonar readings, magnetometer records, and bits of wood and coal brought up by mechanical scoops. The television pictures showed