Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1977 | Volume 29, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1977 | Volume 29, Issue 1

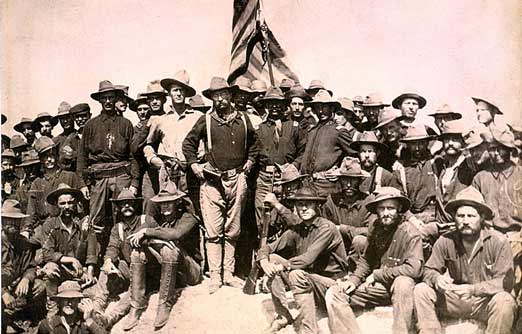

US Army victors on Kettle Hill about July 3, 1898 after the battle of San Juan Hill

From the Revolution at least through World War II, American boys hurrying off to war calmed their fears by believing that their country’s cause wan just and right and would surely prevail.

Young William Ransom Roberts of Traverse City, Michigan, was no exception. Barely nineteen in mid-May of 1898 when President William McKinley called for volunteers to fight against Spain, he rushed to enlist in Hannah‘s Rifles, a unit named for its organizer, a local lumber baron, which was soon mustered into service as part of the Thirty-fourth Michigan Regiment.

Like most of his fellow volunteers, Roberts believed he was embarking on a glorious adventure—to help liberate the brave Cubans from the tyranny of Spain, just as the French had come to the aid of his own embattled ancestors during the Revolution.

Roberts was eager for the fray. “Hurrah!”he wrote when the Thirty-fourth was sent to Fort Alger, Virginia, for training as part of General William R. Shafter’s Fifth Army Corps. And he was equally exultant when, after less than three weeks of desultory drill, his regiment was ordered to Newport News to join the all-Irish Ninth Massachusetts aboard the troopship Harvard, a converted liner.

The glory went out of the war quickly. Within days, Roberts would find himself plunged into the midst of a dirty jungle struggle for which he and his comrades were woefully unprepared.

Through it all, he kept a vivid journal, “Sketches of My Army Life, “which was recently made available to AMERICAN HERITAGE by his niece, Virginia Stevens of New York.

We begin our excerpts from this previously unpublished soldier’s account as Roberts’ troopship passed the battleship Minneapolis on her way out to sea, her destination Cuba.

June 26th

… we were abreast of the Minneapolis. The “Jackies” were all on deck to see us off; three hundred of them all in white duck suits and as we steamed slowly by, three hundred lusty voices sang out to us across the water “Remember the Maine!” There was a seconds stillness before we realized that we were charged by one crew of American sailors to avenge the death of their brothers and then—there was such a roar of two thousand voices that it seemed to come from the bottom of the sea. It came from our hearts and as it went out to them it said “We will.” Did they hear it? Well by their actions I should guess yes: they threw their hats and themselves in the air; they turned hand spring, air springs and cart-wheels; they shouted and we shouted and during the confusion those bad irishmen over our heads called out—Remember the Maine—Remember the Maine—the Irish say to h—l with Spain!!! We watched them until they were out of sight when our attention

We thought we were in luck to be given the steerage passengers berths to sleep in as the rest of the regiment and the 9th had to sleep on the decks but after we were out two days we saw that we had the worst of it for we had no regular place on the decks and it was so hot that to sleep was impossible. The government was paying $3000 a day for the use of that boat. There were enough good berths to accomodate every soldier on board and yet to please the whim of the boats captain we were made to sleep on deck.

The first morning out we had a good stiff breeze and as the old boat rose and fell, a good many of us laid on our backs as if to sleep while others unconsciously nibbled hardtack. A feeling of goneness had attacked us.…

It was noon, June 30th, that we first saw Cuba. She stands very prettily in that southern sea her banks of dark green shrubs and trees rising from fifty to two hundred feet, nearly straight up from the ocean. How good land looked to us and that night when we sailed along the coast, the moon came out and as its rays struck the island and jumped the black shadow caused by the dark green banks, it turned the ocean into a path of silver and gold. A peaceful scene it was. One could hardly imagine that a cruel war had been waged there for so long.…

By daylight every one was up. It was very warm at this early hour. As we were steaming up toward the flag ship again we were warned to keep clear of the guns in Moro Castle. Receiving more orders by signal we then headed for Siboney. The coast from Santiago to Siboney was lined with reporters boats, transports, torpedo boats, armoured cruisers and battle ships.

Anchor was dropped a half mile from shore at Siboney. A large boat was just pulling out from the harbor: a big “red cross” was painted on her bow and a flag of that nature was floating from her stearn: neatly dressed women walked her decks: we knew their significance and cheered until we were hoarse. When the nurses answered us by waving their handkerchiefs we went wild for we had not seen a woman in five days.

Now our attention was called to the 33d [another Michigan regiment, which had arrived in Cuba earlier]. They were on shore and we could just see them as they lined up and boarded, apparently, a work train which soon pulled out and was lost to our view behind some trees and a slight raise in the ground.

On hearing that a march inland was to be

Siboney is not a large town. On one side of its only street is a row of houses and on the other an old mill which has been used for something sometime. The whole reminded me of pictures I had seen in the bible. The houses are plaster with thatched roofs while the trees and plants are principally palms and cactus. It is situated fifteen miles east of Santiago between cliffs seventy-five feet high and the ocean. The tropical birds that were circling around above the cliffs were vultures. What we didn’t like about those birds was that our future relations with them were undecided. We didnt know whether we would be compelled to eat them or whether they might have the chance of eating us. Neither of the prospects being very pleasant to think about very long at a time.

This morning we were divided into groups of six men each and the groups were called mess-gangs. The division was made to enable us to carry our grub to more advantage. One man was supposed to carry a can of beans, another beef and so on. You see we expected we were to have something to eat.…

The unloading had been going on now for a couple of hours and it was now nearly time for our company to start.… Some of our company were getting into the smaller boats. Steps were let down the side of the Harvard to the water line and as a wave would raise the smaller boat near to the steps one of us would jump and by careful aim would land inside. These boats held about twenty men beside the crew. As we got into the life boats, the fellows who had been made sick by the slow rise and fall of the Harvard seemed to get new life from the sharp and jerky motion of the small boat and those who had not been sick seemed to be anxious to get to shore. These fellows amused themselves by feeding the fish. While getting out Art Scott had his finger smashed between the boat and dock. A couple of days later he was sent on board a hospital ship for treatment. Cuban soldiers were gaurding supplies on shore and American soldiers were gaurding the Cubans.

We formed company; crossed a small Creek and marched through Siboney. Naked children were playing everywhere. Women, whose skin was the color of axel grease, stood around in crowds. A Cuban Cavalary man was bidding his friends good bye. He sat proudly on a horse four feet high, the same in length and a foot wide. This horses front legs were knock-kneed and he was bowlegged in the rear.

On the other side of the town, we lined up

The shore west of the landing is coral rock. This, as to fineness of grain and color resembles slate-stone, differing from it in its hardness. The surface resembled a great sponge and as some of the holes were filled with water, a number of us used them for bathtubs. Sitting on a stone sponge in a condition fit for taking a bath is in its most pleasureable moments not comfortable; but by taking our clothes off before our shoes and then sitting on the clothes to take off our shoes we mastered the difficulty. Some of the boys went in at the landing where there was a good beach but the force of the breakers made it to tiresome to be called amusement. After putting up tents we had supper. Some of our mess gang had bought canned peaches and salmon and you can imagine that we relished them after having no dinner and considerable exercise.

Just before supper the 33d came rolling in on oar cars from their fight at Aquadores. They seemed very glad to get back and told “scarey” stories of how it felt to be under fire. They had got as far as the bridge over San Juan River and as the Spaniards had their guns trained on it, Brigadier General Duffeild ordered a hault and there they had been all day: not being able to shoot for the rail-road before the bridge ran through a deep cut and not daring to go ahead for the orders to that effect were not forthcomming. This was the story of a man who was brave enough to say he would rather be at home than under fire.

Immediately after supper orders were received to march inland. Some of us were sent to the landing for cartridges while others were left behind to keep the Cuban beggars from stealing our truck. The young boys and women would pick up the fruit cans we threw away and carry them home when they would melt the covers off and use them for cups. Crowds of

The boys were back with the ammunition now. We were allowed fifty rounds apiece, which we proceeded to place in our belts. At eight o’clock it was “right forward fours right” and we were marching to battle while the band played “Michigan my Michigan.” Some of the company (on account of disability to march) were left with the band to gaurd supplies.

Before starting on this march let us review what training we have had so that we may better realize our condition for undertaking it. There was our march to the Patomac, with little or no drill before it. Three days after this we started on our journey south. Some of us had been sea-sick and we all had had boards to sleep on with very little to eat. We had had very little sleep the night before besides a light breakfast and no dinner today. But what told on us more than any of these things was the intense heat. This was our condition the first night in Cuba and we were about to undertake an eighteen mile march over hills and through mud frequently up to our knees.

Immediately striking into the woods we were greeted with our first whiff of the malaria atmosphere. The ground here never freezes consequently everything falling to the ground rots and gives off an odor resembling that of a pig-sty. Marching in column of fours we measured about a quarter of a mile in length: there being two hundred and fifty two rows with four or five feet between each. In passing a wagon or mud-puddle the column was forced to hault until the first four singled out and passed it; then forward four feet and stop while the next row of fours passed and as we were about the third company from the end, we had to march four feet and stop at least two-hundred times before getting to the wagon. After we got by the wagon we would have to run about a quarter of a mile to make up the distance we had lost by singleing out.

Before we started some of the fellows gave to the Cubans everything that they could possibly get along without and the rest kept the whole outfit. After passing the first wagon and the distance lost by doing so was made up, you could hear those whose burdens were not lightened, swearing in undertones (orders being not to talk out loud) and the next time this jerky form of march was commenced they recklessly threw their packs away and some went so far as to throw their nice blue coats with brass buttons. Consequently the side of the road was strewn with U.S. woolen blankets, coats, tent-poles and halves of pup-tents.

At about this time we opened ranks to let a wounded man pass

Passing into a deep ravine whose banks were covered with trees and the dense under-brush we learned to know so well-one of the boys had just said how easy it might be for a body of Spaniards stationed on the banks over our head to stop us-when; crack! crack! crack! crack! crack! went one or more (?) rifles. For a second all was deathly still. Every one held their breath. Then there was a noise that beggars description: like the stampede of a thousand horses, the trample, the roar of many feet on frozen ground. We could not see but, realized that those ahead were running back. There was a sneaky cry of “to the rear” and we had barely time to push our way as far as possible up into the underbrush; there to turn and sell our lives as dearly as possible, when the Spaniards behind that tumbling, rolling, seething mass proved to be imaginary. As soon as we had lost our places we had found them again and were marching on; very much disgusted with the way the 9th had acted. Now for three or four hours the fellows who belonged ahead of us and who were most active in the retreat, passed us on the way to their places in the column. We were never able to find out who fired those shots. Soon after this we halted for a short rest.

Laying on our packs while we smoked we wondered who among us might tramp the distance to the scene of battle only to retrace his steps, to-morrow, in search of proper care for his wound or whose fate would it be to lie in that tall wet grass dead unconscious of the battle waged around him; or worse still to lie wounded mindful of the din, the roar of the fight and the suffering borne by himself and comrades. Even with this dreary stuff to think of, we enjoyed our pipes and the rest. Just as we were falling asleep the bugle sounded “forward.” It had been just ten minutes since the halt was made.

Now the boys who were wounded at San Juan began to pass us. We were amazed at the cheerful way in which they stood their suffering; laughing and joking with us as they walked on. One of them said “They’ll need you fellows but we’re driving them back.”

For an hour now we were climbing a hill. Its road-bed seemed all mud holes. On the higher land the road turns west towards Santiago. The roads along there were so muddy, we went single file half

Some of us left the column and went on ahead until we came to a creek (I have learned since that Shafters army camped here during the interval of rest before the battle of San Juan); here we laid and slept till the company came along.

We filled our canteens and then crossed the creek by stepping stones. It was daybreak now. I suppose we might have enjoyed the first view of the jungles but we were much to tired to enjoy anything. Stumbling along over stones and through mud puddles for a couple of hours-we came to a hault in front of the division hospital, which is two miles east of El Pozo.

A telephone had been strung up from El Pozo to this place and a reporter was receiving news from the front. The Rough Riders came out, one by one, and galloped off to battle. I counted them there were only sixteen they must have been badly scattered the day before.

An hour was given us here for sleep and breakfast. Going into the feild on our left, we threw our packs and went on to a creek that borders the edge of the feild. Having washed and eaten canned beef and hardtack we laid down in the wet grass and slept.

When we woke up the fireing had begun. Crack, crack, crack, crack, crack, crack, went the rifles. Ld-ld-ld-ld-ld-ld-ld went the gattling guns: zr-r, zr-r, zr-r, sang the bullets and for a background we heard the deep bark of the cannon. We will keep step to lively music this morning. The order to “fall in” is heard and now we are marching to battle.

Squads of “regulars” and pack trains loaded with ammunition passed us on their way to the front. Supply wagons drawn by four or six mules were going to and from the front: those going were loaded with supplies, and comming with the wounded.

Throwing our packs we went on with canteens cartridges and guns for a load. Wading a creek we were halted for a rest. The little block house up on the side of the hill locates El Pozo. It is in our possession now and is being used for a prison. We see perhaps twenty Spanish prisoners marched up to their future quarters. Old Sol is blazing away at us as if to assist the Spanish bullets and we seek the shade of a royal palm just back of the road. A hospital corps is stationed here and the fellow they are working over is a case of sun stroke. Two or three other sick and wounded men are lying around.

Again we started on. The air seemed to vibrate with the intense heat. There wasnt a single muscle in the whole column that didn’t ache and not a head that wasn’t dizzy from the heat. We staggered blindly

At the command, we opened ranks to let something pass. It was a little procession in itself and after seeing many nerve trying things that morning this was a feast to the eye. First came a regular carrying a creg-jorgeson and a mauser also a smile; next a Spaniard whose natural gait seemed to be altered by some force behind; and third, another regular who was administering the force in the form of good wholesome kicks. Were we to tired to cheer? We waded San Juan River now: some of us again filling our canteens.

The bullets seemed to come in sheets and the crack of rifles was very close indeed. Comming out of the wood we immerged into an open field and were soon at the foot of San Juan Hill. Our lines ran along the top of the hill and all of the bullets not stopped by the trenches, whistled over our heads. Pretty soon a little short man on horse back, came up and ordered us farther on. We marched again—a quarter of a mile-and then lay down in a ravine.

Talk about being tired! We layed right down in the sun and went to sleep. In a minute we were awakend by the zipping of steal mauser balls. We went back a short distance and laid in the shade of some small bamboo trees. With my head very close to the roots and my body very close to the ground I was soon asleep again. Awake again—I saw a fellow who was standing on his knees about ten feet away, get hit in the neck: the bullet comming out of his mouth and carrying a piece of his tongue with it. While Captain Wilhelm dressed the wound the bullets sang a fiendish gleeful song around his head. While I was asleep a third time the regiment was ordered to a place of less danger and when I woke up our company had gone. Bullets were clipping twigs from the bushes above my head. The regiment was moving and I must find my company. To do this one had to rise into the atmosphere of bullets. I imagined that to get up there would be like jumping into ice cold water. The company was moving toward San Juan Hill. I hot footed a space and was soon up with them.

We rested on the side of the hill and

The fireing ceased as it grew dark and Sarg’t. Thomas called for volunteers to go for our packs. You see we had been marching all of the night before with only two small meals the day before and today. He soon had enough men and we started out in the moonlight. Only eight more miles on top of nineteen was all. We kept on the dark side of the road: our only danger being from sharp-shooters but that was enough. It had rained before supper and the streams were swollen; as we waded them the water reached our cartridge belts. It seemed a long ways back. Arriving there we cut open the rolls and each of us took as many blankets as we could carry. Another hours walk and we were back to the hill: wet through from wading the creeks and ready to lay down and sleep: which we did right away. We needed a good nights rest. Did we get it? Wait and see.

The enemy at this time were penned in near the city; our lines surrounding them. Their only hope was to break our lines and this they tried to do. The officers braced their men up on whiskey and standing behind the lines, urged them on.

After the exertion we had undergone, one prizes a good nights rest; whether his bed is a mudhole or his own little bed at home. And so we were sleeping soundly; unmindful of the preperations for an attack, going on in the Spanish lines. Orders had been to “sleep on our arms;” which consists in sleeping with belts on and guns at the side. It was at twelve that the noise of the rifles awakened us. We fell in line. At the command “company half left” we took our place in the battalion, then forward and the 34th was climbing the hill. So eager were we all to reach the top of the hill and yet knowing the value of a cool head at such times as these, that each and all of us called out in an undertone to every other man, steady boys, steady-steady. “Halt!” We are half way up the hill but our first battalion is on top.—The Spaniards are trying to break through the lines right above our heads. Our first battalion is there. While we as ill luck would have it, have to stay on the side of the hill until needed.

Listen!

“Load-ready-aim-fire!!” It is our own fellows. How good it sounds.

“Load—ready—aim—fire!!” Again they blaze away at them. It sounds like light artillery, so close together do they shoot.

“Load, ready, aim, fire!!” There is cheering all along the line. They have turned and fled. The fireing stops.

This morning for breakfast we had the same old thing hardtack and beef. After the meal we were moved up on the side of the hill and made to keep in line; ready to move up the hill at a minutes notice. Our time was spent here in marking our equipments and ourselves. It would show our identity if shot and would keep your company men from stealing your truck.

When one man in a company looses something—a canteen or belt, for instance—each man in the company is destined to loose his; but of course he finds one and at about this time some other fellow looses one. Water is sent for about three times a day and while this marking is going on some of the boys are after it. One of the fellows is laying on a comrades lap while a large rent in his trousers are being remmedied. The consideration asked for this work is that if the mender is killed the menace will notify his parents.

On the feild belows us were a squad of negroes hunting sharp-shooters. They seemed to enjoy it as much as we would to hunt partridges. One of them pointed to a large tree bordering on the road we had marched under the day before. After looking a short time we could distinguish three Spaniards trying to hide in the foliage of its topmost branches. Some of the boys aimed at them but they were orderd not to fire. The fireing was not so heavy now but that we could distinguish three seperate vollies from the guns of the negroes and after each volley a sharp-shooter dropped.

It is so hot now we can hardly breathe. By fixing bayonets and sticking our guns in the ground and then fastening the corner of a “poncho” in the gunlock we afford ourselves some protection from the sun. Here we lay and smoke; wishing that rations would come. By general appearances every one seems happy. The canned beef is gone so we only have hardtack for dinner. I must go on a water detail now.

While we were gone a negroe described to us the charge on San Juan Hill.

Our army was lying along the banks of San Juan Creek, which is the last one we waded in getting here. Along its banks dense underbrush grows. With only this brush for protection our fellows were dodgeing the bullets from the lines on the hill and the sharpshooters back of them. The bullets came to thick and fast for our fellows to dodge them all; so the hospital corps were busy careing for the wounded and laying the dead to one side. They had been

It rained before supper and a few of us constructed a shelter tent with our ponchos and guns; using the guns for poles, a blanket on top and three for the sides. This made the tent flat on top and it was from the water filling the slack in our top blanket that we learnt to catch to use. From this little house we watched the fellows get soaked while we were as dry as we cared to be. It stopped raining just before dark and we were called from the hut for roll-call.

The sides of old San Juan are clay and after a rain, as you cant slide up hill, it is a pretty hard hill to climb. Halfway up the side our fellows were trying to line up. Those who were lucky enough to be near bushes hung to them: these fellows acted as posts while the others clinging together anchored at the posts at different points along the line and thus our position was secure while the sargeant called roll.

We eat our breakfast of hardtack and then talk of the fun we could have at home and the fun that the people their are probably having. There is no fireing this morning and we learn we are under a flag of truce. How long it will last none of us know. Here shade is at a premium and this morning three of us climbed to a tree, near the top of the hill, where we lay and talked and by bracing our feet against the trunk we keep from sliding down. We see our company going to a wagon and getting spades, picks and shovels; this means work if we are recognized: so we stop talking and lay with our hats covering our faces and try to sleep. They begin digging a shelf in the side of the hill. We watch them from under broad rimmed hats until a flat space one hundred by seven or eight feet, is dug. Several times Sargeant has glanced up at us as though wondering who we were. Now he calls us and we don’t answer but when the captains voice is heard we go down

As the twenty of us who went for the rolls, could not bring them all, a detail is sent after the remainder. The rest of us mark out places on the shelf where we intend to sleep. Throwing away the large stones that we do not care to sleep on: they roll down the hill and strike some member of Company A in the calf and small of their back. This gives rise to some hard talk but it soon stops.

When the fellows come back with the rolls we each take a poncho or pup tent and tying the sides of them all together, we raise them by means of poles driven in the ground and have a roof over our shelf. Our beds are made of grass over which a half pup tent is thrown. Rations come now and with yelling and shouting we run down to meet them. To-night for supper we have hard-tack fried in “sowbelly” grease and coffee with sugar in it. It has rained but little this afternoon and on account of the slippery condition of the hill we are told we must build steps up it tomorrow.

This morning every one takes a good long time to slice of his piece of “sowbelly”: there is no lean in it at all, just pure grease. This was a sickly diet for a country where the mercury rises from one-hundred and thirty to thirty five in the shade; but let me say that when men have been almost fasting for two weeks, they could eat tallow and relish it. We pick our way carefully down the hill; where, after finding some wood we have a small fire blazing and our “sow-belly” soon sizzles in the frying-pans; while, we on the windward side—to keep clear of the smoke—drop in a hard tack. Frying it untill brown on one side it is turned while the other side has a chance. Five or six hardtack are fried in this manner and by the time our last hardtack is brown, the coffee which was ground with a bayonet and placed on the fire first, is done and picking up our belongings we climb the hill. Before leaving the fire and thereby loosing our right of possession, a friend is called who has been waiting such a chance and it is given him.

Looking back and thinking of a number of delicious meals I have eaten there comes to my mind pictures of nice rooms, clean plates, shining silverware and long bills of fare with high sounding names on them and fine tasting stuff to correspond with the names; but praise Heaven for the “eternal fitness of things” for

After breakfast and roll is called, men from each company are detailed to dig a trench in the hill, large enough for the whole regiment to lie in during the next fight. There was also a detail appointed from our company to build steps up the hill. It was so awful hot that after working ten minutes in the sun you must lie down ten to be able to work again.

Tonight the regimental intrenchment at the top of the hill is done by night and this with the company shelves one above another like large steps, make the hill look as if it might be the residence of cliff-dwellers. We are to use the larger one for a gaurd house untill such time as we need it for protection.

This morning our company lined up and with a wagon of pix and shovels we start out to bury the dead. Of course the majority were already covered and peices of cracker boxes used for head boards identified them: there were some however, who had been missed and others who were not wholly covered. Dead horses and mules lay exposed to the air and it was our duty to see that every-thing, man or beast, was properly covered up.

By the time the first creek was reached, it was raining. Getting out ponchos, we waited for the wagon. Some of us washed in the stream and now the wagon appears. Throwing rolls and guns in the wagon we were soon at work. The first that we found was only half buried, his head, hands and feet being exposed. Vermine were eating his flesh. Covering him quickly we went on. The next creek had been bridged with large bamboo poles. It was surprising to see how strong it was. Loaded supply wagons could cross safely. Farther down the road we came upon the 2nd battalion encamped on the left hand side. They had built the bridge and were now working on the roads. We did not envy their job.

Nearing the division hospital we came to a mangoe-tree filling our shirts with the fruit we passed on-happy because we were eating. Now a man came along selling newspapers for a dime. Nearly all invested and arriving at the hospital, we devoured news two weeks old while resting. Here the captain bought tobacco which was divided among us. This was as far as we had to go. Sixteen had been buried besides a few dead horses and mules. On the way home the wagon is tipped over throwing out guns, rolls, pix and shovels besides the captain and a few others. Arriving at the hill-rations had arrived and

Tonight it is cool and sitting around on blankets and think of our extra fine supper. Leiut comes up and says a dead Spaniard lies not far away and he call for volunteers to bury him. By his odor we soon locate him and find we have a jackass to bury.

Every one every time he has a chance leaves camp and goes to one of the creeks to bath or explores the surrounding country. This afternoon three of us cross the f eild over which the charge of July 1st was made. Going slow on account of tall grass, we pass carefully around graves of the fallen heroes and are soon at the creek. How good the bath feels! It is the first time we have washed in a week after perspiring gallons each day. Washing our clothes we put the[m] right on for their is no danger of colds here.

When we got to camp some of the fellows, who were on gaurd last night and had slept in the gaurd house, were telling of the peculiar sensations one is liable to have when a spider as large as a fist crawls over his arm or leg. Here comes the sergeant with a slip of paper in one hand and a pencil in the other: this means work and two of us who have just been in swimming are ordered to patrol the creek for a mile and arrest any one caught bathing or washing their clothes there. What we did was to allow them all to go in with the injunction that if an officer appear, to say that they were just ordered out and were getting there as fast as circumstances of the case would premit. I came upon a man bathing a wounded f orhead. He said he received it just as his regiment immerged from the woods and were about to charge the hill. The bullet had just grazed his temple. “Oh you belong to the nigger regiment.” (I had not noticed his features and he was nearly white) “Yes” said he “I belong to the colored troops.” Seeing he was somewhat chagrined over being called a nigger I told him of a letter I had found near a dead mans coat. It ran thus. “Dear Boy:-although us colored people is looked down upon by the whites, we owe them a great deal for giving us our liberty. I hope you will do your duty and show them we merit their respect. Hoping you are well etc. Your Uncle.” He had given his life for a country whose people did not respect the manhood under his black skin. Niggers I called colored people after this. We got back about seven o’clock and eat supper in the dark.

Orders are to roll up and prepare to move. With rolls on our back we stand around for an hour then swing into line and march toward El Pozo. When we get there companies B. and M. move around the block house and go into camp while the rest of the regiment move toward the division hospital. About twelve of company M. are immediately sent farther down the road to do out post duty. There is no water near their post and all they have is two canteens a piece to last twenty four hours. There is not a breath of air stirring and everything-grass, trees, shrubs, stones-fairly sparkle from the sun’s rays. Some of the boys nearly faint but a breeze soon rises and we all feel better.

Enormous crabs and turantulas have been seen in the bushes so tonight a number of us sleep in the road. For a wonder it did not rain today and the road is dry and hard: but the hardness feels good to our lame backs. After eating a few mangoes, we fall asleep.

The company has received no mail since leaving Camp Alger—June 23d. We seem to be in another world. This morning I sent a letter by team to Siboney. I wonder when it will reach home. There is no regular duty for us to do to-day; so we lay around telling stories and mending our clothes or wander in the woods looking for relics. Some of us find cast off overhall suits—thrown away by regulars during the fight—and these we keep and wear while we stay on the island. Twelve more men were sent to relieve the out post. Those comming back said it was a snap.

The boys who were left at Siboney came back this afternoon. They had seen Alexander who they said was very sick but thought he would pull through all right. One of the Co. B. fellows had been stationed on the Harvard to gaurd prisoners and he told of their effort to over-power the gaurds and escape. Pat had bored a hole through one of these fellows with a springfield rifle ball. A few of them jumped overboard and swam for shore but were shot on their way.

We received rations today; consisting of soap, one-quarter of a candle for two men, a handf ull of beans apiece, hardtack, coffee and sow-belly besides a can of beef for three men.

This morning a crowd gathered at the creek to wash their clothes and bath-the result of soap being issued yesterday.

There is a species of poison oak here that effects the skin as our ivy at home does. It looks much like a small oak tree except that the limbs branch out from the top like a palm and on the edge of the leaves are little thorns. Two of us fellows were victims of this poison from the start and just returned

On our way to camp we were met by the 2nd sargeant who advised us to hurry to camp as we were about to move. That was the way. Whenever we were settled nicely so at to enjoy our camp we had to move.

We were now packed up. The out posts had come in and the main body of the regiment now appeared; having evidently marched a good ways. They marched on up the road and companies B. and M. fell in behind. It was up hill all the way and hot again too. How to describe that intense heat “staggers” me. To realize the hotness of that heat you must experience it. You must be there in that column of men who seemingly exert all their strength every step they take, to take that step and yet the column keeps in motion

The companies ahead of us keep falling out at different places along the road, to do gaurd duty. We meet and pass a regiment of regulars whose place we are about to take. Climbing innumerable hills and strength nearly spent we come to a cleared space on a high hill where four of our feild guns are stationed. There is brush piled up before the guns. We do not want them to know where we are. Passing on we are compelled to go in single file for this path twists and turns up and down and around the side of the mountain like a snake. We go slow to keep from tripping over stones and as we dodge the branch of a poison oak, we frighten enormous mountain crabs who go crawling away; their hard shell making a scraping noise as they hit the stones. At last we come to a level space at the end of the range of hills. Here we lay and rest while we wait for orders. Major Hodgekins and Sergeant came along and together they went down the hill to see where they might best place gaurds. Before long they came back and ordered twelve men with a sergeant to camp near the battery the remainder of the company staid here. Two of the boys were stationed on a large stone near the top of the hill and three of us were sent to the foot of the hill and stationed on a road along which the Spaniards might come if they broke through our lines. We kneeled down in the grass to be clear of sharpshooters and with watches out we waited for the time when the fireing was to commence and as we waited we thought of the comparative strength of the two armies. Spains army numbers twenty-five thousand, ours ten.

The fireing is begun by a huge gun located on the hills back of us. The shell goes shreiking into the city. A few rifles crack out along the line: Thirty six big guns clear their throats and bark while they belch forth fire and iron destruction and death into Spanish territory: The cracking of twenty thousand rifles adds a little to the noise: Rapid fire guns pop out two-hundred bullets a minute at Spanish heads just showing above the intrenchments: Listen-Sampson, twelve miles away, is letting us know the he is there. As our shells shreik into their city and our bullets whistle gayley around their ears, dont feel sorry for them. Ours are not the only shells that shreik and their bullets are aimed very nicely. The earth trembles from this throbbing pounding load of sound.

Darkness comes on and the fireing slacks somewhat. Three miles north of us we see a mortar gun spit fire and some seconds after, the report comes to us. As the fireing stops, we keep sharp watch along the road. Hark! there is a noise in the bushes at our right. As a sergeant and six men come from the bushes, they run into the muzzles of three rifles and halt. They take our places and we climb the hill. Not so very fast though for the path was a hard one to come down when there was plenty of light and so we get off the trail and stumble around in the cactus vines for an hour before reaching the top. Here several of the boys have spread there blankets while the rest of the company sleep on the side of the hill. We lay down and are soon sleeping soundly.

The fireing starts at day-break and we are ordered to cook breakfast on the side of the hill so they cannot locate us by our fires. San Juan after a rain is very hard to climb; but the only way to get up or down this hill is by hanging on the limb of a tree until a safe resting place for your feet is found.

Those of us who wished to see the fight were ordered to keep well out of sight. At the northwest corner of our hill was a little flat space and here behind the bushes we watched the battle. We might have considered ourselves out of the fight entirely if their shells

At night when the lights of the city sparkled brightly the moon would come out and send down a flood of light to dance on the rippled waters of the harbor and myriads of stars looking down at us from their quiet watch in heaven would seem to say “children why do you quarrel.” The battle of the day before would fade to insignificance compared with the earth and her playfellows in the sky.