Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1977, Summer 2025 | Volume 28, Issue 4

Authors: Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1977, Summer 2025 | Volume 28, Issue 4

Nearly two centuries after Crèvecoeur propounded his notorious question—“What then is the American, this new man?”—Vine Deloria, Jr., an American Indian writing in the Bicentennial year on the subject “The North Americans” for Crisis, a magazine directed to American blacks, concluded: “No one really knows at the present time what America really is.” Surely few observers were more entitled to wonder at the continuing mystery than those who could accurately claim the designation Original American. Surely no audience had more right to share the bafflement than one made up of descendants of slaves.

But we are all baffled by the meaning of the American experience. All any of us can do is descry a figure in the carpet—realizing as we do that contemporary preoccupations define our own definitions. My effort here will be to suggest two themes that seem to me to have subsisted in subtle counterpoint since the time when English-speaking white men first began the invasion of America. Both have dwelt within the American mind and struggled for its possession through the course of our history. Their competition will doubtless continue for the rest of the life of the nation. This essay aims to present these rival themes and to propose some points about the relationship between the divergent outlooks and the health of the republic.

I will call one theme the tradition and the other the countertradition, thereby betraying at once my own bias. The tradition, as I prefer to style it, sprang initially from historic Christianity as mediated by Augustine and Calvin. The Calvinist ethos was suffused with convictions of the depravity of man, of the awful precariousness of human existence, of the vanity of mortals under the judgment of a pitiless and wrathful deity. Harriet Beecher Stowe recalled the atmosphere in Oldlown Folks: “The underlying foundation of life … in New England, was one of profound, unutterable, and therefore unuttered, melancholy, which regarded human existence itself as a ghastly risk, and, in the case of the vast majority of human beings, an inconceivable misfortune.”

So terrible a sense of the nakedness of the human condition turned all of life into an unending and implacable process of testing. “We must look upon our selves,” said William Stoughton, the chief justice of the court that condemned the Salem witches, “as under a solemn divine Probation; it hath been and it is a Probation-time, even to this whole People.…” So had it been at all times for all people. Most had failed the test. Were the American colonists immune to the universal law?

In the Calvinist view, all secular communities were finite and problematic; all flourished and all decayed; all had a beginning and an

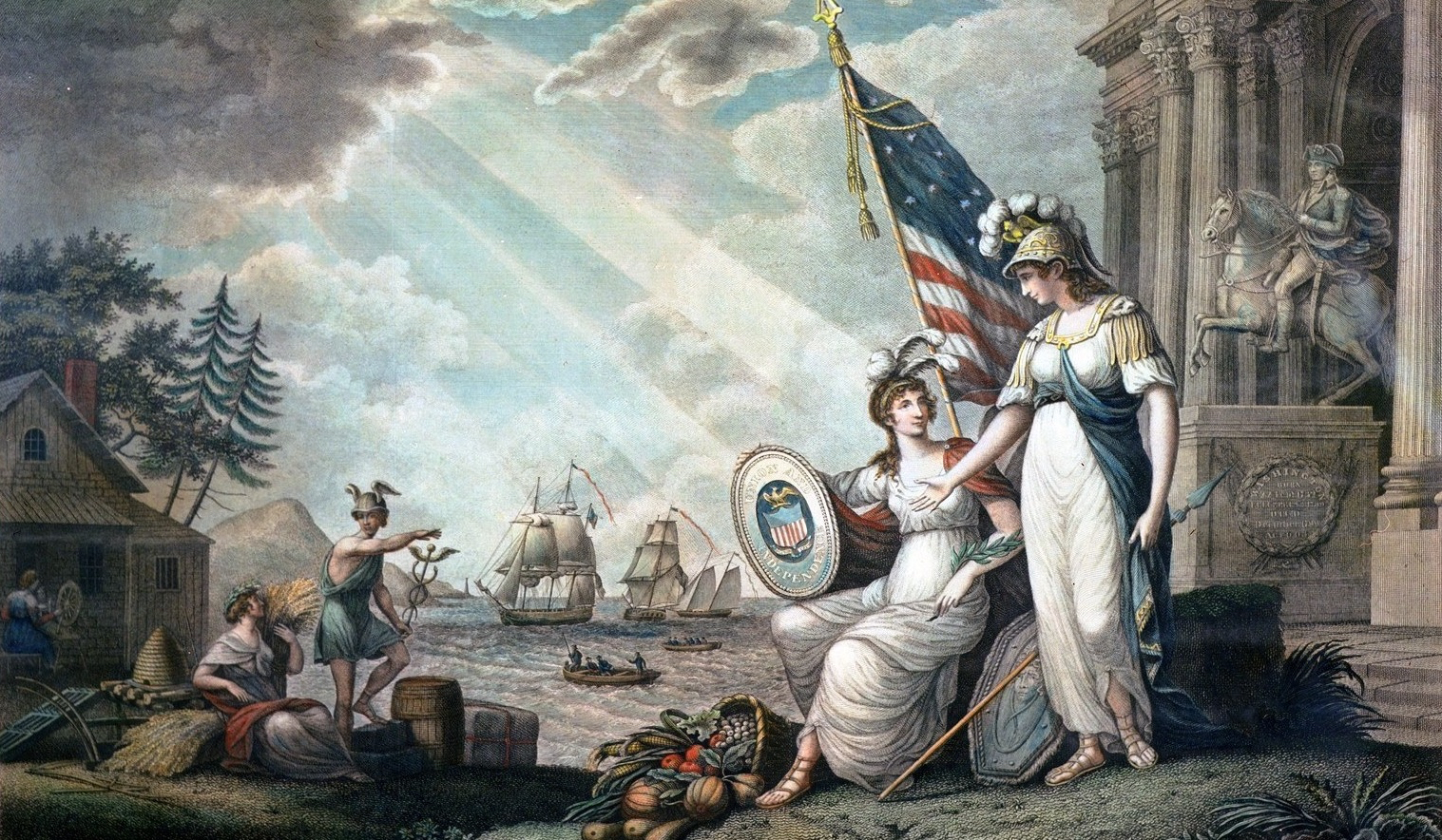

From different premises, Calvinists and classicists reached the same conclusion about the fragility of human striving. Antiquity haunted the Federal imagination. The Founding Fathers had embarked on a singular adventure—the adventure of a republic. “The Roman republic,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist, “attained to the pinnacle of human greatness.” In this conviction the first generation of the American republic designed its buildings, wrote its epics, named the upper chamber of its legislature, signed its greatest political treatise “Publius,” sculpted its heroes in togas, organized the Society of the Cincinnati, and instructed the young. There was plausibility in the parallel. There was also warning. For the grandeur that was Rome had come to an inglorious end. Could the United States of America hope to do better?

The Founding Fathers passionately ransacked the classical historians for ways to escape the classical fate. But the classical indoctrination reinforced the Calvinist judgment that this was probation-time for America. For the history of antiquity did not teach the inevitability of progress. It proved rather the perishability of republics, the subversion of virtue by power and luxury, the transience of glory, the mutability of human affairs. The apprehension of the mortality of states was a vital element in the sensibility of Philadelphia in 1787. Not only was man vulnerable through his propensity to sin, but republics were vulnerable through their propensity to corruption. The dread of corruption, as Professor Bernard Bailyn has demonstrated, was readily imported from England to the colonies. History showed that, in the unceasing contest between corruption and virtue, corruption had always—at least up to 1776—triumphed.

The Founding Fathers had an intense conviction of the improbability of their undertaking. Such assets as they possessed came in their view from geographical and demographic advantage, not from divine intercession. Benjamin Franklin ascribed the inevitability of American independence to such mundane factors as population increase and vacant lands, not to providential design. But even these assets could not be counted on to prevail against history and human

Hamilton said in the New York ratifying convention, “The tendency of things will be to depart from the republican standard. This is the real disposition of human nature.” If Hamilton be discounted as a temperamental pessimist or a disaffected adventurer, his great adversaries were not always more sanguine about the republic’s future. “Commerce, luxury, and avarice have destroyed every republican government,” Adams wrote Benjamin Rush in 1808. “… We mortals cannot work miracles; we struggle in vain against the constitution and course of nature.” “I tremble for my country,” Jefferson had said in the 1780’s, “when I reflect that God is just.” Though he was trembling at this point—rightly and presciently—over the problem of slavery, he also trembled chronically in the nineties over the unlikely prospect of “monarchy.” In 1798 he saw the Alien and Sedition Acts as tending to drive the states “into revolution and blood, and [to] furnish new calumnies against republican government, and new pretexts for those who wish it to be believed, that man cannot be governed but by a rod of iron.”

This pervasive self-doubt, this urgent sense of the precariousness of the national existence, was no doubt nourished by European assessments of the American prospect. For eminent and influential Europeans regarded the New World, not as an idyl of Lockean felicity—“in the beginning, all the world was America”—but as a disgusting scene of degeneracy and impotence.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the famous Buffon lent the weight of scientific authority to the proposition that life in the Western Hemisphere was consigned to biological inferiority. American animals were smaller and weaker; European animals shrank when transported across the Atlantic, except, Buffon specified, for the fortunate pig. As for the natives of the fallen continent, they too were small and weak, passive and backward.

No one made this case more irritatingly and perseveringly than Abbé Raynal in France. His much-reprinted work, Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and of the Commerce of Europeans in the Two Indies, first published in 1770, explained how European innocence was under siege by American depravity. America, Raynal wrote, had “poured all the sources of corruption on Europe.” The search for American riches brutalized the European intruder. The climate and soil of America caused the European species, human as well as animal, to deteriorate. “The men have less strength and less courage … and are but little susceptible of the lively and powerful sentiment of love—a comment that perhaps revealed Raynal in the end more as a Frenchman than as an abbé.

The Founding Fathers were highly sensitive to the proposition that America was a mistake. Franklin, who thought Raynal an “ill-informed and evil-minded Writer,” once endured a monologue by the diminutive abbé on the inferiority of the Americans at his own dinner table in Paris. “Let us try this question by the fact before us,” said Franklin, calling on his guests to stand up and measure themselves

Though the Founders were both indignant and effective in their rebuttal, the nature of the attack could hardly have increased their confidence in the future of their adventure. The European doubt, along with the Calvinist judgment and the classical pessimism, made them acutely aware of the chanciness of an extraordinary enterprise. From the fate of the Greek city-states and the fall of the Roman Empire, they drew somber conclusions about the prospects of the American republic. They had no illusions about the inviolability of America to history, nor about the perfectibility of man, Americans or others. The Constitution, James Bryce has well said, was “the work of men who believed in original sin, and were resolved to leave open for transgressors no door which they could possibly shut.”

We have all applied the phrase “end of innocence” to one or another stage of American history. This is surely an amiable flourish—or a pernicious delusion. No people who systematically enslaved black men and killed red men could be innocent. No people reared on Calvin and Tacitus, on Jonathan Edwards and the Federalist, could be innocent. No nation founded on invasion, conquest, and slaughter could be innocent. No state established by revolution and thereafter rent by civil war could be innocent. The Constitution was hardly the product of immaculate conception. The Founding Fathers were not a band of saints. They were brave and imperturbable realists who committed themselves, in defiance of the available lessons of history and theology, to a monumental gamble.

This is why Hamilton, in the third sentence of the first Federalist, formulated the issue as he did. The American people, he wrote, had the opportunity “by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” So Washington defined it in his first Inaugural Address: “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered, perhaps, as deeply, as finally, staked on the experiment intrusted to the hands of the American people.” The Founding Fathers saw the American republic not as a consecration but as the test against history of a hypothesis.

Washington’s early successors, with mingled anxiety and hope, reported on the experiment’s fortunes. In his last message to Congress, James Madison permitted himself “the proud reflection that the American people have reached in safety and success their fortieth year as an independent nation.” “Our institutions,” said James Monroe in his last message, “form an important epoch in the history of the civilized world. On their preservation

How is one to account for this rising optimism? It was partly a tribute, reasonable enough, to survival. It was partly the spread-eagleism and vainglory congenial to a youthful nationalism. It was no doubt also in part admonitory exhortation, for the Presidents of the middle period must have known in their bones that the American experiment was confronting its fiercest internal trial. No one understood more profoundly the chanciness of the adventure than the young man who spoke in 1838 on “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions” before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. Over most of the first half century, Abraham Lincoln said, America had been felt “to be an undecided experiment; now, it is understood to be a successful one.” But success contained its own perils; “with the catching, end the pleasures of the chase.” As the memory of the Revolution receded, the pillars of the temple of liberty were crumbling away. “That temple must fall, unless we … supply their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason.” The conviction of the incertitude of life informed his Presidency—and explained its greatness. His first message to Congress asked whether all republics had an “inherent and fatal weakness.” At the Gettysburg cemetery he described the great civil war as “testing” whether any nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal “can long endure.”

This was, then, a dominant theme of the early republic—the idea of America as an experiment, undertaken in defiance of history, fraught with risk, problematic in outcome. But a countertradition was also emerging—and, as the mounting presidential optimism suggests, with accumulating momentum. The countertradition, too, had its roots in the Calvinist ethos.

Historic Christianity embraced two divergent thoughts: that all people were immediate unto God; and that some were more immediate than others. At first, Calvin had written in the Institutes, God “chose the Jews as his very own flock.” Then, with what Edwards called “the abolishing of the

It was not only that they were, in Winthrop’s words, as a City upon a Hill, with the eyes of all people upon them. It was that they had been despatched to New England, as Edward Johnson said, by a Wonder-working Providence because “this is the place where the Lord will create a new Heaven, and a new Earth.” The “Lord Christ” intended “to make his New England Souldiers the very wonder of this Age.” The fact that God had withheld America so long—until the Reformation purified the church, until the invention of printing spread the Bible among the people—argued that He had been preparing it for some ultimate manifestation of His grace. God, said Winthrop, having “smitten all the other Churches before our eyes,” had reserved America for those whom He meant “ to save out of this generall calamitie,” as he had once sent the ark to save Noah. The new land was certainly a part, perhaps the climax, of redemptive history; America was divine prophecy fulfilled. The achievement of independence gave new status to this theory. The Reverend Timothy Dwight, Jonathan Edwards’ grandson, called Americans “this chosen race.” “God’s mercies to New England,” wrote Harriet Beecher Stowe, daughter of one minister, wife of another, foreshadowed “the glorious future of the United States … commissioned to bear the light of liberty and religion through all the earth and to bring in the great millennial day, when wars should cease and the whole world, released from the thralldom of evil, should rejoice in the light of the Lord.” “We Americans,” wrote the youthful Herman Melville, “are the peculiar, chosen people—the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of the liberties of the world.... Long enough have we been skeptics with regard to ourselves, and doubted whether, indeed, the political Messiah had come. But he has come in us.” The belief that Americans were a chosen people did not imply a sure and tranquil journey to salvation. As the Bible made amply clear, chosen people underwent the harshest

It was a short step from the Social Gospel at home to Americans carrying the Social Gospel to the world. In 1898 the Reverend Alexander Blackburn, who had been wounded at Chickamauga, spoke of “the imperialism of righteousness”; and from Blackburn to the messianic demagoguery of Albert J. Beveridge was only another short step: “God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation. … And of all our race He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world.” So the impression developed that in the United States of America the Almighty had contrived a nation unique in its virtue and magnanimity, exempt from the motives that governed all other states. “America is the only idealistic nation in the world,” said Woodrow Wilson on his pilgrimage to the West in 1919. “… The heart of this people is pure. The heart of this people is true. … It is the great idealistic force of history.... I, for one, believe more profoundly than in anything else human in the destiny of the United States. I believe that she has a spiritual energy in her which no other nation can contribute to the liberation of mankind....” In another forty years the theory of America as the savior of the world received the furious imprimatur of John Foster Dulles, another Presbyterian elder, and from there roared on to the horrors of Vietnam. So the hallucination brought the republic from the original idea of America as exemplary experiment to the recent idea of America as mankind’s designated judge, jury, and executioner. Nor are we yet absolutely clear that the victor in the Bicentennial election may not believe that nations, like Presidents, may be born again. Why did the conviction of the corruptibility of men and the vulnerability of states—and the consequent idea of America as experiment—give way to the myth of innocence and the delusion of a sacred mission and a sanctified destiny? The

We find ourselves now, for all the show-business clatter of the Bicentennial celebrations, an essentially historyless people. Businessmen agree with the elder Henry Ford that history is bunk. The young no longer study history. Intellectuals turn their backs on history in the enthusiasm for the ahistorical behavioral “sciences.” As the American historical consciousness has thinned out, the messianic hope has flowed into the vacuum. Experiment has given ground to destiny as the premise of national life. So the theory of the elect nation, the redeemer nation, the happy empire of perfect wisdom and perfect virtue, almost became the official creed. Yet, while the countertradition prospered, the tradition did not quite expire. Some continued to regard it all as the deceitful dream of a golden age, wondering perhaps why the Almighty should have chosen the Americans. “The Almighty,” Lincoln insisted at his second Inaugural, “has His own purposes.” He clearly knew what he was saying, because he wrote soon thereafter to a fellow ironist, Thurlow Weed: “Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however … is to deny that there is a God governing the world.” After the war, Walt Whitman, once the supreme poet of democratic faith, suddenly perceived a dark and threatening future. The experiment was in jeopardy. These States, no longer a sure thing, were caught up in a “battle, advancing, retreating, between democracy’s convictions, aspirations, and the people’s crudeness, vice, caprices.” America, Whitman apprehended, might well “prove the most tremendous failure of time.” “’Tis a wild democracy,” Emerson said in his last public address; “the riot of mediocrities and dishonesties and fudges.” A fourth generation of Adamses raised particularly keen doubts whether Providence in settling America had after all opened a grand design to emancipate mankind. Henry Adams began as a connoisseur of political ironies; later he became a sort of reverse millennialist, convinced that science and technology were rushing the planet toward an apocalypse unredeemed by a Day of Judgment. “At the rate of increase of speed and momentum, as calculated on the last fifty years,” he wrote in 1901, “the present society must break its damn neck in a definite, but remote, time, not exceeding fifty years more.” The United States, like everything else, was finished. In

William James, the philosopher, retained the experimental faith, abhorring the fatalisms and absolutes implied by “the idol of a national destiny … which for some inscrutable reason it has become infamous to disbelieve in or refuse.” We are instructed, James said, “to be missionaries of civilization.... We must sow our ideals, plant our order, impose our God. The individual lives are nothing. Our duty and ourdestiny call, and civilization must go on. Could there be a more damning indictment of that whole bloated idol termed ‘modern civilization’?” All this had come about too fast “for the older American nature not to feel the shock.” One cannot know what James meant by “the older American nature”; but he plainly rejected the supposition that American motives were, by definition, pure; and that the United States enjoyed a divine immunity to temptation and corruption. Like the authors of the Federalist, James was a realist. “Angelic impulses and predatory lusts,” he precisely wrote, “divide our heart exactly as they divide the heart of other countries.” So the warfare between realism and messianism, between experiment and destiny, continued to our own day. If some political leaders were messianists, the perception of America as an experiment conducted by mortals of limited wisdom and power without divine guarantee informed the practical intelligence of others. The second Roosevelt saw life as uncertain and the national destiny as problematic. The republic was still an experiment and “demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.” Roosevelt’s realism kept American participation in the Second World War closer to a sense of national interest than of world mission. In a later time John Kennedy argued that antimessianic case: “We must face the fact that the United States is neither omnipotent nor omniscient—that we are only 6 per cent of the world’s population—that we cannot impose our will upon the other 94 per cent of mankind—that we cannot right every wrong or reverse each adversity—and that therefore there cannot be an American solution to every world problem.” “Before my term has ended,” he said in his first annual message, “we shall have to test anew whether a nation organized and governed such as ours can endure. The outcome is by no means certain.” This evoked the mood of the Founding Fathers. But the belief in national righteousness and providential destiny remains strong—a splendid triumph of dogma over experience. One cannot but feel that this belief has encouraged our recent excesses in the world and that the republic has lost much by forgetting what James called “the older American nature.” For messianism is an illusion. No nation is

Yet we retain one signal and extraordinary advantage over most nations—an entirely secular advantage, conferred upon us by those quite astonishing Founding Fathers. For they bequeathed us standards by which to set our course and judge our performance—and, since they were exceptional men, the standards have not been rendered obsolete even by the second law of thermodynamics. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution establish goals, imply commitments, and measure failures. The men who signed the Declaration, said Lincoln, “meant to set up a standard maxim for a free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.” We can take pride in our nation, not as we pretend to a commission from God and a sacred destiny, but as we struggle to fulfill our deepest values in an inscrutable world. As we begin our third century, we may well be entering our golden age. But we would be ill advised to reject the apprehensions of the Founding Fathers. Indeed, a due heed to those ancient anxieties may alone save us in the future. For America remains an experiment. The outcome is by no means certain. Only at our peril can we forget the possibility that the republic will end like Gatsby in Scott Fitzgerald’s emblematic fable—Gatsby who had come so long a way and whose “dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night. “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.... And one fine morning— “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” COPYRIGHT© 1977 BY ARTHUR M. SCHLESINGER,JR.