Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May/June 1987, Summer 2025 | Volume 38, Issue 4

Authors: Richard B. Morris

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May/June 1987, Summer 2025 | Volume 38, Issue 4

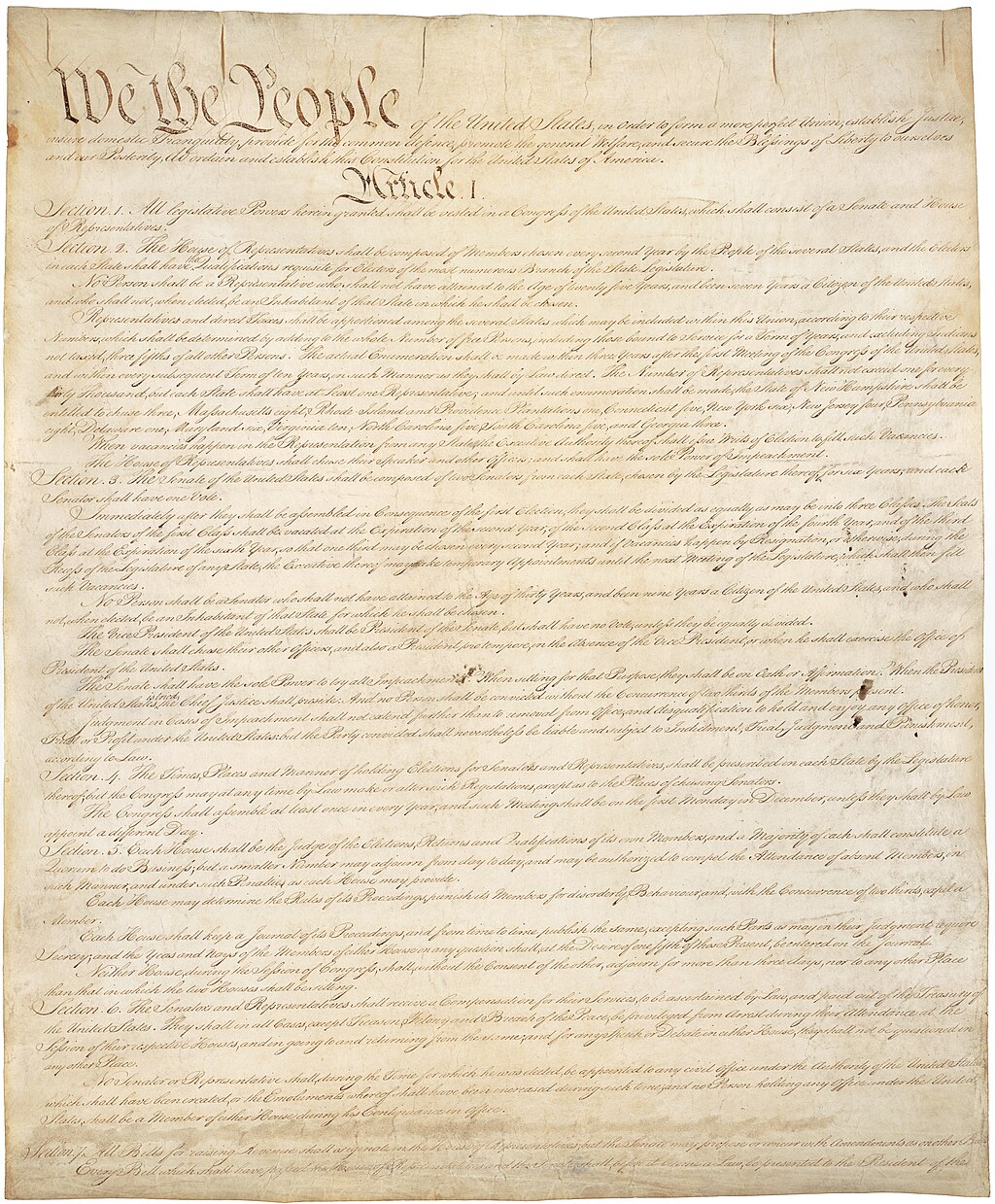

The American Constitution has functioned and endured longer than any other written constitution of the modern era. It imbues the nation with energy to act while restraining its agents from acting improperly. It safeguards our liberties and establishes a government of laws, not of men and women. Above all, the Constitution is the mortar that binds the fifty-state edifice under the concept of federalism; it is the symbol that unifies nearly 250 million people of different origins, races, and religions into a single nation.

Over two centuries dozens of constitutions adopted in other countries have gone into the scrap heap. The United States Constitution has outlived almost all its successors. The longevity of the Constitution makes us wonder whether its thirty-nine signers planned it that way, and if they did, why doesn’t the Constitution declare itself to be perpetual, unlike the weak “perpetual” union—the Articles of Confederation—that it succeeded? Somehow the adjective was overlooked in the federal convention, while the word compact was deliberately avoided in a vain attempt to forestall the issue of whether the Constitution was a compact between the states, which any party could disavow, or between the government and the people, which States’ Righters might have found unacceptable.

However, the Constitution does start with a hint that it was aiming for longevity. The Preamble, in Gouverneur Morris’s incomparable language, says that its purpose is “to form a more perfect Union” and “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity....” President Washington in his Farewell Address speaks of the “efficacy and permanency of your union.” Nevertheless, both the supremacy and the permanence of the Constitution were to be challenged within a decade. To oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, which curbed the actions of hostile aliens and held the press criminally accountable for “false” and “malicious” writings about the government, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson joined forces to write the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. These asserted that a state had the power to “interpose” when the government exceeded its powers as enumerated in the Constitution.

By 1828 the challenge of “interposition” had become the threat of “nullification” when John C. Calhoun endorsed South Carolina’s refusal to obey a new tariff measure. In spite of vigorous support by Daniel Webster and President Andrew Jackson, the life-span of the Constitution seemed jeopardized on the eve of the Civil War as “nullification” gave way to “secession,” and the Southern states claimed that the Constitution was dissoluble at the pleasure of any state that might wish to secede.

Confronted by a burgeoning secessionist movement, President Lincoln

One of the clues to the mystery of the Constitution’s durability is the plastic quality that makes it applicable to a rapidly changing society. At the convention it was the Committee of Detail’s deliberate intention, in the words of its draftsman, Edmund Randolph, “to insert essential principles only” in order to accommodate the Constitution “to times and events” and “to use simple and precise language, and general propositions....” Randolph’s notion of confining a constitution to broad principles was a masterstroke that contributed immensely to that document’s enduring suitability and relevance, and James Wilson of Pennsylvania contributed further by putting Randolph’s draft into smoother prose. Finally, the Committee of Style and Arrangement, under the swift and sure guidance of Gouverneur Morris and his talented colleagues, gave us the final draft, a masterpiece of conciseness.

How different, indeed, from most modern state constitutions, which are often hugely long with their general principles buried under a heap of minute local and transitory details. The great charter, a few parchment pages adopted in eighty-four working days, is a broad blueprint of governance, timeless in character.

Another aspect of the working methods of the framers helps explain the relatively speedy adoption and ratification of the Constitution. In 1839, on the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the national government, John Quincy Adams spoke of the federal Constitution as having been “extorted” from the “grinding necessity of a reluctant nation.” He was attesting to the fact that only a combination of bold innovation, compromise, and concession made it possible to frame and ratify the Constitution. Adams may well have been overstating the case, for in fact, the overwhelming majority of the delegates to the Philadelphia convention were nationalists of one sort or another, convinced of the need to confer a taxing power on a central government, to invest it with jurisdiction over foreign and interstate commerce, and to establish a framework that would be the supreme law of the land.

Within this extraordinary company of statesmen there developed sharp differences about how such a constitution could be made to conform to truly republican principles, how vestiges of sovereignty could be left to the states, just what powers should be enumerated to the national (or federal) government, and how far the states could be restrained.

School texts invariably refer to the Great Compromise by which the small states gained equality in the Senate while the House of Representatives was made proportional to population. But even within that compromise, credited to the Connecticut delegates, there were additional compromises. Once it was settled that the House was to be elected by the people, the issue arose as to how the Senate was to be elected—also by the people, as the democratic nationalist James Wilson proposed; or by the House, as Edmund Randolph recommended; or by the state legislatures, an idea set forth by John Dickinson. The last suggestion was the one adopted, and it was a tribute to the delegates’ concern about setting up a federal rather than a national constitution, thereby recognizing that certain powers inhered to the states. The Senate represented the states, and Article V of the Constitution guaranteed that no state could be deprived of equal suffrage in the Senate. This equality of the fifty states is a cardinal element of our federal system, reinforced by the Tenth Amendment, according to which “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

On the issue of choosing senators, James Wilson’s vision proved the sharpest, for the Senate came in later years to be perceived as a tool of the big business interests that tended to dominate the state legislatures. The Seventeenth Amendment, which was ratified in 1913, provided for direct election of senators by the people, vindicating Wilson’s original judgment. While the large states won proportional representation in the House, the Northern states could hardly be expected to permit the South to count blacks, who were not eligible to vote, for purposes of that representation. Nor did the South care to include its slave population in the head count that would determine the amount of taxes it would have to pay in direct taxation. The result: Another compromise by which representation and direct taxes in the lower house would be based on “free persons,” including servants bound for a term of years (a favored labor source of white labor in the tobacco states of Maryland and Virginia), and three-fifths of all other persons, “excluding Indians not taxed....” As a result, in counting population a black was included as three-fifths of a white person. The compromise gave something to each side: for the South, more Southerners to be represented in Congress; for the North, more heads to tax.

If the Great Compromise resolved differences between the states about representation, the second major compromise resulted from a confrontation between North and South about commerce. Everyone had agreed that conferring power over

Nonetheless, every regional concession brought its price and begot its compromise. Thus, the great slavery issue came to the fore when the delegates took up the matter of import and export duties. The South pro- posed that Congress be forbidden from levying a tax on the importation of slaves or from prohibiting their importation altogether. Virginians, who were finding slavery less profitable than did their more southerly neighbors, did not join the Southern bloc. Nevertheless, over the objections of Virginia’s great libertarian George Mason and of a divided North, the delegates worked out a compromise whereby no prohibition on the importation of “such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit” could be permitted before the year 1808. Even the North was split on this crucial and emotional vote. Nor was there a solid South.

In this way was slavery acknowledged, though not by name in the Constitution, and confirmed in two other compromises: the three-fifths rule for representation to the House of Representatives and for direct taxes and the provision for the return to their owners of fugitive persons “held to Service or Labor....”

And the Philadelphia delegates continued to compromise. First, it was decided that the chief executive was to be a single person, not a committee or plural executive, as previously had been proposed. He would serve for four years (other proposals had ranged from a life term to a single seven-year term), and he was to be eligible for reelection. He would have a qualified veto (one that could be overridden by the legislative branch), not the absolute veto that some had urged. He would not be chosen by Congress, as the Virginia Plan had proposed, or selected directly by the people, as James Wilson would have preferred. Instead, the final decision, after countless proposals, was to have the President elected by electors who would be chosen in each state “in such Manner” as its legislators might “direct.” This plan, perhaps conceived to propitiate the states, proved instead a victory for both nationalism and democracy, for very shortly after 1789 nearly all the state legislators provided for the election of their states’ presidential electors by popular vote. If no candidate had a majority of the electoral vote, the ultimate choice would be made from the

Perhaps the ablest defense of all these compromises and concessions was made in The Federalist, in which Madison, while conceding that the Constitution was not a “faultless” document, admitted that the convention’s delegates “were either satisfactorily accommodated by the final act; or were induced to accede to it out of a deep conviction of the necessity of sacrificing private opinions and partial interests to the public good, and by a despair of seeing this necessity diminished by the delays or by new experiments.”

Finally, and certainly most important in terms of the safeguards for the people, the chief criticism leveled against the Constitution when it was finally submitted for ratification was the failure to incorporate a bill of rights. In ratifying the Constitution, a number of states included bills of rights among their recommendations. To ensure such compliance, New York even urged that a second convention be called. The prospect of another convention, which might very well undo the great work already accomplished, appalled James Madison. Once elected to the House of Representatives, the Virginian reduced more than two hundred proposed amendments to twelve, of which ten were ratified. The Bill of Rights, as those first ten amendments are called, proved to be the great concession that quieted public fears about the new government’s guarantees of civil liberties. This concession was Madison’s noblest heritage to the nation.

If there was controversy from the very start about the scope and intent of the Constitution, that controversy has continued down to the present day. In fact, it has heated up over the current insistence of the attorney general, Edwin Meese, that the Supreme Court in interpreting the Constitution is bound by the intent of the framers. This question, now being debated in many quarters, addresses the public’s conception of the Constitution: Is it a charter carved in stone or a malleable document that can be interpreted in response to rapidly changing moral and social values and economic and technological demands? When Hamilton described the Constitution as looking “forward to remote futurity,” how flexible did he consider it to be?

Are courts bound by the debates at the convention and the state ratifying conventions, or are they bound by the “express words” of the Constitution, and are we talking about the meaning of those words in 1787 or in the 1980s? Certainly the meaning that the drafters wished to communicate may differ from the meaning the reader is warranted to derive from the text.

What we do know, in studying the notes of debates of the framing of the Constitution, is that the framers’ expected the Constitution to be interpreted in accord with its express

Since the proceedings of the convention were secret and mostly not published until after James Madison’s death some fifty years later, there is no possibility that the framers wished future interpreters to extract intention from their private debates. Nevertheless, in the debates over ratification, the Antifederalists expressed worries that the Congress and the federal judiciary would construe broadly the enumerated powers. At the New York ratification convention John Jay sought to allay these fears by insisting that the document involved “no sophistry, no construction, no false glosses, but simple inference from the obvious operation of things.” And Madison took pains to point out that improper construction of the Constitution could be remedied through amendment or by election “of more faithful representatives to annul the acts of the usurpers.”

One of the most revealing examples of determining the intent of the framers occurred in their own later arguments about the “necessary and proper” clause. Article I, Section 8 lists among the powers granted Congress: “To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.” Now it so happens that both James Madison and Alexander Hamilton served on the Committee of Style that was responsible for the final wording of the Constitution. In The Federalist No. 44 Madison argued for a liberal interpretation of the “necessary and proper” clause in a way that must have delighted Hamilton, who was later to take the same position in defending the creation of the First Bank of the United States. The convention had in fact rejected a proposal to give Congress explicit power to charter corporations. Only after Madison had become involved with Jefferson in what amounted to the opposition party’s assault on Hamilton’s financial policies did Madison in effect repudiate his Federalist position and adopt the theory of “strict construction.”

Yet it was to be Hamilton’s interpretation of the scope of the “necessary and proper” clause that President Washington accepted and that Chief Justice John Marshall later embraced. Indeed, Hamilton anticipated the later assumption by the Supreme Court of powers for the federal government on the basis of three clauses of the Constitution, which, in addition to the “necessary and proper” clause, included the general welfare clause—granting Congress power “to provide for the...general Welfare of the United States”—and the commerce clause, giving Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes....” There is no question that we today owe to the vision of the framers a Constitution that can accommodate the modern welfare state under the general welfare clause and manufacturing within the commerce

In The Federalist No. 37 Madison, then sharing Hamilton’s views, argued that the “intent” of any legal document is the product of the interpretive process, not of some fixed meaning that the author locks into the document’s text at the outset. He ventured so far as to declare that even the meaning of God’s Word “is rendered dim and doubtful by the cloudy medium through which it is communicated” when He “condescends to address mankind in their own language....” It was up to the courts, Hamilton argued in a later Federalist letter, to fix the meaning and operation of laws, including the Constitution, and the courts could be expected to use the “rules of common sense” to determine the “natural and obvious sense” of the Constitution’s provisions.

The question of the intention of the Philadelphia framers came up in one of the first great and controversial decisions handed down by the Supreme Court presided over by John Jay. Chishom v. Georgia (1793) raised the question, Could a state be sued by a private citizen of another state? The language of the Constitution was, to say the least, ambiguous; according to Article III, federal judicial power could extend to controversies “between a State and Citizens of another State....” In the debates on ratification the framers went to great pains to deny that the Constitution would affect the state’s sovereign immunity. Even Hamilton gave such assurances in The Federalist No. 81. Yet a majority of the Court, construing the wording of Article HI, held that the text was intended to allow suits against a state. But Georgia did not think so, and few amendments overruling a Supreme Court decision were adopted more speedily than the Eleventh Amendment, which in 1798 upheld the states’ immunity to such actions.

How much weight did James Madison, often called the “father of the Constitution,” give to the original intent of the framers? Very little, it seems, if we can judge from his insistence in his later years that “as a guide to expounding and applying the provisions of the Constitution, the debates and incidental decisions of the Convention can have no authoritative character.” What counted in Madison’s eyes were precedents derived from “authoritative, deliberate and continued decisions.” Madison, who had originally phrased the Bill of Rights, sought to bind the states as well as Congress—a phrasing that mysteriously disappeared from the final product, which speaks only of Congress. He would have rejoiced at the modern Supreme Court’s interpretation of the truly revolutionary Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868 during the Reconstruction Era and holding that the states as well as the federal government are bound by the Bill of Rights.

Indeed, what has contributed to the durability of the Constitution is its capacity to adapt to a society so different from that of the Founding Fathers. Shortly before the

The Constitution made provision for such adjustments. Even though the word equality is missing in that seminal charter, in time amendments were adopted that, among other things, ended slavery (ratified in 1865), provided for “the equal protection of the laws” and “due process of law” for all persons (ratified 1868); conferred voting rights regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (ratified 1870); required the direct election of senators (ratified 1913); gave women the suffrage (ratified 1920); ended the poll tax as a bar to voting in federal elections (ratified 1964); and extended the suffrage to eighteen-year-olds (ratified 1971).

But not by amendments alone has the Constitution been reshaped. Actions of the three branches of government have broadened its text and applied its principles to specific situations only dimly perceived by the framers. As early as George Washington’s administration the principle of executive privilege was upheld, the rights of the President to dismiss appointees accepted, the cabinet—not mentioned in the Constitution—created, the right of the President to declare neutrality without consulting the Senate established, and the House of Representatives’ power to withhold appropriations for treaties it did not approve of overruled. Finally, there emerged a party system—a system that none of the Founding Fathers anticipated—that Washington deplored in his Farewell Address, and that was considered a cause of faction and divisiveness. Yet today political parties are accepted as the touchstone of a democratic society, and the repression of opposition parties as one of the most visible symptoms of a totalitarian state.

Despite these enlargements and glosses upon the original Constitution made by both the President and Congress over the past two centuries, it is the High Court that bears the brunt of criticism for straying from the intent of the framers. Critics charge the Supreme Court with practicing what amounts to judicial legislation to effect due process, achieve equal justice, assure voting equality, and maintain the right of privacy even in cases in which it is dubious that a majority of the nation’s citizens support some of its advanced positions.

In 1787 and 1788 and again today critics contend that judges, who are insulated from the electoral process, should not be entrusted with final interpretation of the laws. But no federal judge has ever been impeached and removed from the bench because his decisions have run counter to public opinion. Only on grounds

That independence is the central issue concerning the federal judiciary’s role today. The Supreme Court is increasingly preoccupied with cases that deal with social and moral issues—the death penalty, desegregation, school busing, prayer in schools, abortion, privacy —and litigants insist that the justices fill the vacuum created by the lack of direction on these subjects from the two other branches of government that, unlike the Court, are subject to the electoral process.

No single branch of the government can long evade the issue of accountability for interpreting the Constitution. The President fills vacancies on the Court, usually picking persons who reflect his constitutional views. In requiring the President to swear to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution,” the public expects him to determine if and when it is being threatened. Some Presidents, like Lincoln, looked neither to Congress nor to the courts in times of crisis. Deciding that the Union was indissoluble, Lincoln explicitly assumed the authority and took on the full burden of maintaining the Union.

Nor can Congress escape responsibility, since it is charged by the Constitution with enacting regulations concerning the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction except when spelled out in Article III. Beginning with the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress has set the parameters of the federal courts’ jurisdiction and within those constitutional limitations can enlarge or diminish the scope of litigation that may be brought to trial in the federal courts.

Finally, we the people have the power of defining the Constitution through the ballot box, albeit that power has seldom been used directly to affect judicial decisions. The most startling exception was in 1936, when, not long after the election, the Supreme Court in obvious response to public opinion began to yield to the President’s and Congress’s constitutional views. But that example was dramatic and virtually without parallel. Indeed, few citizens consciously or systematically utilize their ballots to register constitutional interpretations. This omission leaves officials to resolve most conflicts themselves, but senators, representatives, and Presidents do so subject to the disapproval of voters, whereas the Court is politically unaccountable.

True, the Constitution contains a provision for amendment by calling a convention, but the framers, having themselves violated their instructions by overthrowing rather than revising the Articles of Confederation, were loath to expose their great work to a second convention. And despite the number of states that in recent years have gone on record to call for such a second convention, the wording of the calls are varied and imprecise and the dangers to the durable structure of the nation seem too great to bear the risk.

In the landmark case of Cohens v. Virginia (1821), Chief Justice John Marshall spoke of a constitution as having been “framed for ages to

In the century ahead it should continue to function so long as it can meet the objectives that were set forth in the Preamble in the name of “We the People”: to “insure domestic Tranquillity, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity....” For two hundred complex years it has remained steadfast to these goals. No worthier aims can be set for the great charter as it moves into its third century.

TO FIND OUT MORE

In the vast literature about our Constitution and the convention that created it, the works fall into three general categories: primary sources that scholars rely on; books written by historians based on those sources; and popular treatments by authors writing for a wider, more general audience. According to Richard B. Morris, two particularly valuable books in the second category have been newly reissued in paperback for this anniversary year. They are Clinton Rossiter’s1787: The Grand Convention (Norton) and Carl Van Doren’s The Great Rehearsal (Penguin). He also recommends The Creation of the American Republic, by Gordon S. Wood (Norton). Dr. Morris’s own new book examines the intellectual antecedents of the Constitution, surveys the nation that gave it birth, and ends with its writing and ratification. Among more popular books on the subject are Catherine Drinker Bowen’s recently reissued Miracle at Philadelphia.