Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 1

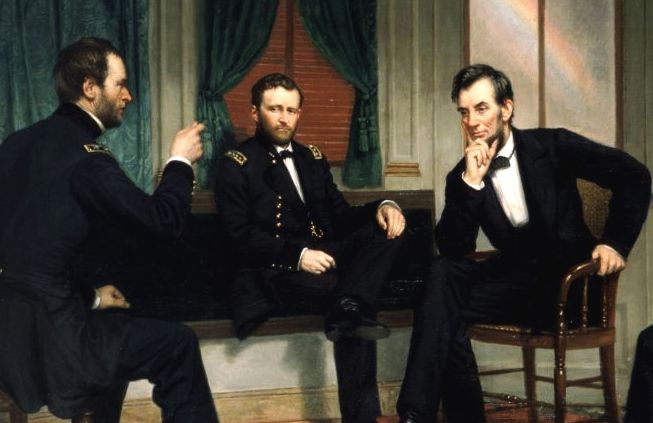

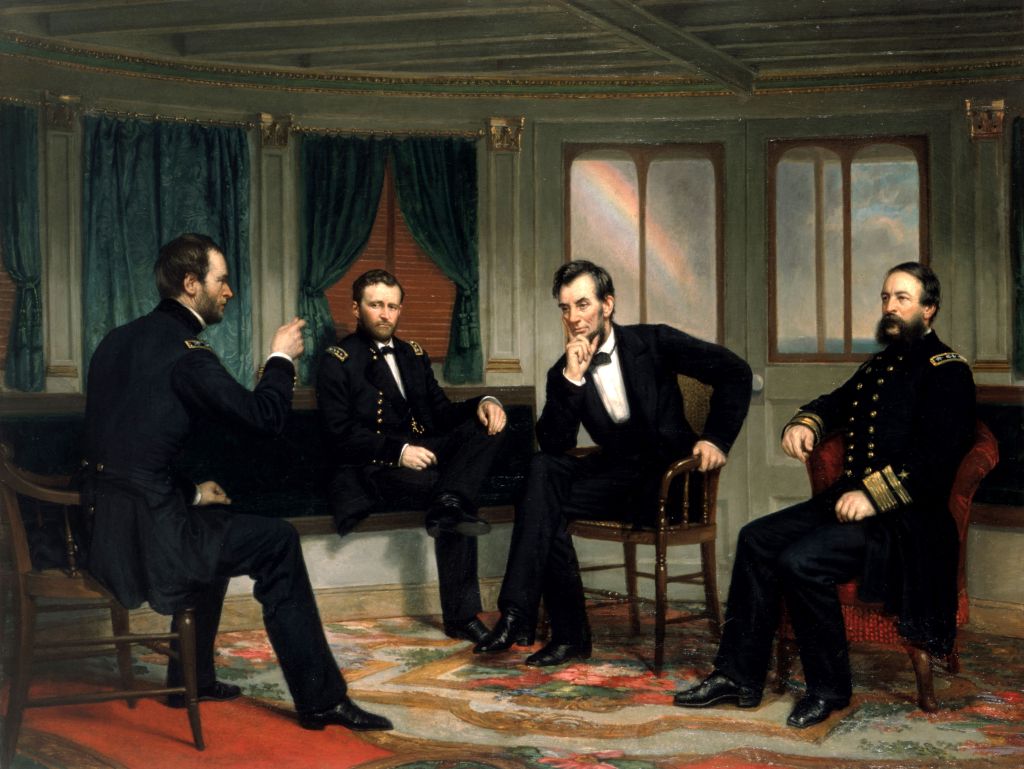

From the moment he was first inspired to paint it, George Peter Alexander Healy harbored huge ambitions for the canvas he entitled The Peacemakers. The artist longed for it to be universally embraced as “a true historical picture,” cherished as the emblem of sectional reconciliation following the Civil War.

It was not to be. At least not until now, thanks to an unexpected renaissance in its reputation, one inspired by another president, another artist, and another painting. It may sound unfathomable, but credit George Bush with thus giving Abraham Lincoln an image boost this year.

The original problem with Healy’s tribute to peace was that it actually portrayed a council of war—a March 28, 1865, strategy session by the Union high command aboard the side-wheeler River Queen, anchored off City Point, Virginia.

The so-called peacemakers who Healy depicted were far better known for crushing the enemy than for coddling them: William T. Sherman, fresh from making “Georgia howl” on his march to the sea; Ulysses S. Grant, famed for bulldog ruthlessness in battle; Admiral David Dixon Porter, who commanded the starvation-inducing Union blockading squadron; and Abraham Lincoln himself, whom at least half the country blamed for the death and suffering inflicted by the war. This was not a dramatis personae associated with peace. The inconsistency may have doomed the painting’s reputation even before it was completed, but its iconography was further muddled by seeming chiefly designed to celebrate not Lincoln but the artist’s “dear friend” Sherman.

The general, a notoriously uncooperative sitter—during the war he had told one artist to “go to a hot place” when asked to pose—not only sat for Healy but persuaded Grant to cooperate as well, even though his old commander’s first reaction was: “I have sat so often for portraits that I had determined not to sit again.” Sherman even got Porter to provide detailed diagrams of the shipboard cabin where the conference had taken place.

Healy repaid this debt by making Sherman the dominant figure of a picture ostensibly designed to celebrate Lincoln’s policy of “malice toward none.”

The public reacted skeptically. A chromo-lithograph adaptation was published, but judging by the rarity of surviving prints, it proved unpopular. Print audiences evidently preferred fanciful scenes of Lincoln’s ascent into heaven to realistic ones of his wartime strategy sessions. Then, worst of all, Healy’s huge five-and-a-half-by-four-foot canvas, completed in Rome in 1868, was destroyed by fire.

But the intrepid artist had made several copies before losing the original, and eventually the White House acquired one of them, although it was later relegated to the private upstairs rooms. Gone but not forgotten, The Peacemakers at least remained familiar through ubiquitous illustrations in books and magazines. Now, propelled by an odd twist of