Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 8

Authors: Robert K. Krick

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 8

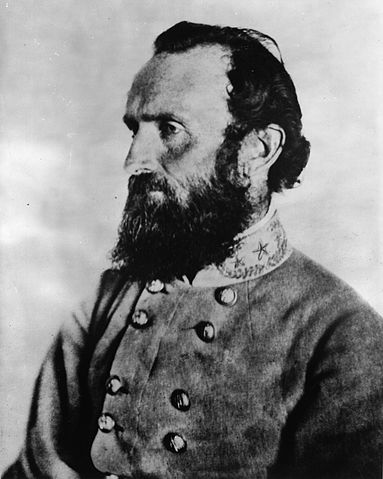

“THERE WAS A WITHCERY IN his name,” a Mississippian wrote, “which carried confidence to friend and terror to foe,” Northerners victimized by Stonewall Jackson’s daring thrusts were hardly less laudatory. General Gouverneur K. Warren, on the verge of becoming a Federal hero at Gettysburg, wrote on hearing of Jackson’s death that he rejoiced for the Union cause, “and yet in my soldier’s heart I cannot but see him the best soldier of all this war, and grieve at his untimely end.” A New York newspaper praised Jackson as a “military genius” and declared, “Nowhere else will the name of Jackson be more honored.”

Americans North and South marveled—and still do—at Jackson’s exploits and at the rigid, pious, eminently determined person who produced them. He was in some ways so unlike his fellows but in many others so ordinary.

A confederate attending an 1897 reunion in Los Angeles read a short poem to his assembled comrades. Its reminiscent look at the mythic images of Jackson and Robert E. Lee closes with a couplet that deftly evokes the two: “…now and then/Through dimming mist we see/The deadly calm of Stonewall’s face/The lion-front of Lee.” That deadly calm continues to bemuse observers. It prompted a modern popular film producer in a fit of silliness to call Jackson a blue-eyed assassin. Serious students of the war respond to the imagery in ways that often reveal more about themselves than about the militant Presbyterian deacon who came, with Lee, to symbolize the Confederacy.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson (1824–63) reached the eve of the great American war without revealing any hint that he had the makings of a legend. For a land enamored of rags-to-riches tales, he personified the noble concept of rising from humble origins. Orphaned at an early age, sheltered in the homes of a series of relatives, ill educated, Tom Jackson reached his late teens without any real prospects for modest success, to say nothing of greatness. A chance to enter the United States Military Academy at West Point opened new vistas. It also threw in young Jackson’s path the intimidating prospect of competing in a rigorous academic environment with boys vastly better prepared for the challenge.

Nothing soluble by sheer hard work ever daunted Jackson. The youngster from western Virginia stayed in the West Point Hotel’s attic on June 19, 1842, and the next day began the academy’s entrance examinations. When the testing ended, his name appeared dead last on the list approved for admission. He applied himself to West Point’s curriculum with the same implacable determination that later made him a terror to his foes. A classmate recalled that his “efforts at the blackboard were sometimes painful to witness.” Whatever the problem

The sweat—and long nights of cramming by candlelight—paid off. Jackson managed to finish fifty-first out of eighty-three class members at the end of his first year. He improved steadily to stand thirtieth and twentieth in succeeding classes, then graduated seventeenth in 1846. His grades the last year received a boost from the class on ethics (or logic), in which he ranked near the top. A contemporary at the academy suggested that had the curriculum run a year or two longer, Jackson would have reached the head of his class. At the end of his third year at West Point, the rigidly disciplined young man stood first in conduct among all 204 cadets.

Once he had become world-famous, his West Point contemporaries tried to recollect anecdotes about him. One of them admitted that Jackson had been “so modest and retiring…as to be but little known.” Unfortunately Cadet Jackson’s roommate George Stoneman, who would command the Unionist cavalry opposing Lieutenant General Jackson at Chancellorsville, left no testimony about their days at West Point.

Jackson’s Mexican interlude also prompted the dawning of a religious awareness that would blossom into one of his defining characteristics. During his youth Jackson’s irregular upbringing had included more horse racing than piety. A story about his siring an illegitimate child is unsubstantiatable and probably inaccurate, but its acceptance by some of Jackson’s Confederate staff suggests their awareness of a past completely alien to the rigidly decorous adult. In 1847, the Catholic culture of occupied Mexico stimulated Major Jackson to examine the Roman Church’s tenets and practices with real interest. A few years later his religious nature settled on Calvinism, and he embraced Presbyterianism with all the zeal of a spectacularly ardent soul, becoming what his pastor called “the best deacon I ever had.”

Jackson spent less than three years in the Army after leaving Mexico, being posted first to Fort Hamilton, near New York, and then to Fort Meade, in Florida. Proximity to New York’s bookstores and libraries gave him an opportunity to exercise a relentless bent toward self-improvement. He wrote earnestly in 1849 to the congressman

The Florida assignment offered little chance for self-improvement or anything else attractive. Fort Meade, not far southeast of Tampa, faced no Seminole threat; instead its warfare raged within the post, between Jackson and his commander, Maj. William H. French. One of Jackson’s peers at West Point had noticed how a petty misdeed by another cadet, “prompted only by laziness,” had seemed to Jackson “to show a moral depravity disgracing to humanity.” That meddlesome inflexibility now led Major Jackson to attack French (whose pregnant wife was at the post) with an endless array of charges over what Jackson thought was moral turpitude involving a female nursemaid. Reviewing the flood of paper generated by the squabble leaves a modern reader uncertain about French’s guilt—and not much interested in the question (which is about how the two officers’ superiors felt at the time). A crusade that unquestionably struck Jackson as a solemn duty now looks like pettifoggery.

In the short term, Jackson’s righteous campaign at Fort Meade turned out badly for everyone involved, as could easily have been predicted. Weary and demoralized, he resigned to take a position at the emerging military college in Lexington, Virginia. The result was entirely salutary. He found contentment in Lexington, fell in love twice there, and developed into the mature man who would exploit the opportunities fate offered him a few years later. The Virginia mountain town enchanted Jackson (as it still does those who visit). “Of all the places that have come under my observation in the United States,” the major wrote emphatically, “this little village is the most beautiful.”

He also found satisfaction in his role in the community and with his neighbors, declaring himself “delighted with my duties, the place and the people.” However, although the terse and somewhat eccentric professor clearly had the respect of his neighbors, he “certainly did not have their admiration,” a contemporary wrote. Then and later, he was as far from convivial as a man could readily be.

His rigidity, undiluted by pragmatism, made the Virginia Military Institute cadets dislike him. They called him Square Box, a derisive tribute to his imposing boot size, and at times would sneak into his classroom to draw an immense foot on the chalkboard. Cadets delighted in falling into lockstep

Jackson never did unravel the intricacies of effective public discourse, nor did he learn to endear himself to his charges. He weathered a formal investigation of his classroom performance by the Board of Visitors, made at the insistence of the institute’s alumni association. He also survived an attempt on his life by a cadet who had been the undeserving victim of his rigidity; the cadet went on to become a Confederate general, and, after Jackson’s death, commanded his former tormentor’s old brigade.

For his part, Jackson liked much about academic life. He contemplated writing a textbook on optics and collaborated with a brother-in-law on the design of a military school opening in North Carolina. Had he taken to that new opportunity, he probably would have commanded North Carolina troops in 1861—with an impact on his career and on the course of the Civil War that is unknowable but fascinating to contemplate. The famed Stonewall Brigade, five sturdy Virginia regiments, never would have existed, nor could Jackson have become Stonewall at Manassas. Would Thomas Jackson sans nickname have succeeded as dramatically without the magical circumstances that attended his career in Virginia?

HIS PROFESSIONAL experiences during the decade in Lexington did much to mold him, but his domestic life probably made an even deeper impression. Jackson’s relationships with three women during the 1850s—two wives and a sister-in-law—reveal aspects of the man that do not fit the randomly constructed legend that obscures him. In the summer of 1853 Jackson married Elinor Junkin, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who was president of Washington College. The major’s tender, loving attentions to Ellie would have astonished those who saw only his public austerity. Fourteen months after their marriage Ellie Jackson died in childbirth (the baby, a boy, died too). Thomas held Ellie’s hand as it turned cold. He was never quite the same thereafter. A few hours later, he wrote to a West Point mate, “I desire no more days on the Earth.”

Ellie Jackson’s sister, Margaret Junkin (later M. J. Preston, and known as Maggie), was one of the brightest, most literate women in the South. Her poetry and prose received wide publication in an era when female writers were supposed to aspire to private circulation only. An 1857 autobiographical novel by Junkin limns Ellie and Maggie, with a thinly disguised Jackson in the background. This woman of erudite, inquisitive, creative mind became

In 1857, he was married again, to Mary Anna Morrison, the sweet-tempered daughter of another college president and Presbyterian preacher. Love letters, many of which survive, show that again Jackson’s marriage was marked by a tenderness at odds with his public image. In November 1862 Anna bore his only surviving child. Stern notions of duty kept the proud father, by then a world-renowned lieutenant general, from going to see the baby—or even allowing his family to visit him—until late the next April. By then Jackson had only a few days to live. He had meanwhile assuaged his yearning for children by cultivating the enchanting five-year-old daughter of his hosts during the winter of 1862–63. Almost as though cursed with her admirer’s bad domestic luck, little Jane Wellford Corbin died of a sudden, violent childhood disease a few hours after General Jackson moved his headquarters away from her home.

By 1861, Major Jackson had become a familiar figure to a few hundred residents of Lexington and its environs and a few hundred more Virginia Military Institute men. Had the Civil War not offered him a stringent new environment in which his remarkable abilities would be revealed, he would have remained all but unknown. It is hard to imagine that the histories of his city and county, or even of the institute where he taught, would have mentioned him in more than a footnote next to other names now long forgotten. The war supplied a dramatically different stage upon which to strut, one for which he was uniquely suited.

One moment crucial to his career, and even more essential to the legend, came at the crisis of the Battle of First Manassas (or the First Battle of Bull Run, as Yankees called it) on July 21, 1861. While the Confederate tactical situation deteriorated all around him, Jackson held his brigade of five Virginia regiments to their duty with characteristic resolution. A South Carolinian hoping to inspire his own troops pointed out Jackson standing “like a stone wall.”

The general deserved every bit of the credit bestowed upon him for the stand at Manassas, but the nickname was of course purely happenstance. What he soon achieved at the head of his troops in Virginia catapulted him to worldwide renown. Had he accomplished precisely what he did, however, under a less riveting label than “Stonewall,” the Jackson legend might not have maintained quite the grip it has on the popular imagination. Consider by contrast the names of the Confederate generals Nathan

Jackson spent the twenty-two months of life left to him after First Manassas validating his nom de guerre . After a months-long sitzkrieg in Virginia and the collapse of Southern frontiers in the Western theater, he electrified the Confederacy with his dazzling Shenandoah Valley campaign during the spring of 1862. Southerners used to bad news idolized the only one of their leaders demonstrating aggressive instincts and delivering good news. The fabulous Valley campaign demonstrates what made Jackson great. He began it with a mere thirty-five hundred troops. In addition to being overwhelmingly outnumbered, he faced a strategic imperative that limited his options: His paramount obligation was to keep as many Federals as possible anchored in the Valley and thus out of the force building against Richmond. To achieve that end, Jackson struck with characteristic boldness and energy at the Battle of Kernstown on March 23, 1862. He lost the tactical honors but forced his enemies to remain in the Valley when they had started to leave.

For the next six weeks, Jackson either retreated or lurked in the arms of the mountains, patiently pulling Federals southward and isolating them from other duty. At the end of April the Confederates dashed east out of the Valley, only to return at once by train and then march rapidly west to win a victory in the Alleghenies at McDowell on May 8. Reinforcements available to Jackson because of that victory, and others he managed to wangle from east of the Valley, gave him the wherewithal to take the offensive for the first time. In a series of long, rapid marches and daring thrusts, he won battles at Front Royal and Winchester on May 23 and 25.

To magnify his successes, he boldly lunged all the way to the Potomac, with deadly effect on the thinking of Federals in Washington. At the last possible moment he scurried back through a bottleneck between two Federal columns closing in on his line of retreat and marched south through torrential rains. The climax of the campaign came on June 8 and 9, with two incredible victories in succession, at Cross Keys and Port Republic. Jackson’s carefully calculated daring had won its way past razor-thin enemy troops yet again.

With the Valley won, Jackson pushed east toward Richmond to help Robert E. Lee, newly in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, lift the encirclement of the capital city. During the Seven Days’ Battles the siege was ended, but more despite Stonewall’s participation than because of it. For the only time during the war, Jackson

But no one had any occasion to wonder about Jackson over the next ten months; he and Lee cemented a skilled collaboration (“I would follow him blindfolded,” Jackson said) that discomfited the Federals at every turn. After he had won the Battle of Cedar Mountain as an independent commander on August 9, 1862, Stonewall joined Lee in a daring initiative that outmaneuvered the Unionists at Second Manassas. That victory opened the way for a raid across the Potomac during which Jackson captured 13,00 enemy troops at Harpers Ferry, then commanded half of Lee’s line above Antietam Creek during the Battle of Antietam. In December Jackson’s corps took part in the easy, bloody repulse of an immense Federal army at Fredericksburg.

The deft complementary relationship between Lee and Jackson reached its pinnacle at Chancellorsville in May 1863. Although outnumbered by more than two to one (about 130,000 to 60,000), the two Virginians contrived to befuddle Gen. Joseph Hooker, commanding the opposing Army of the Potomac. In a maneuver that, typically, Lee proposed and Jackson executed flawlessly, the Confederates marched thirty thousand men around their enemy’s flank. When Jackson’s legions came screaming out of the woods behind Hooker’s line, they routed onethird of the Federal army. They also marked at that moment the apogee of the Confederate nation’s fortunes.

A few hours later Jackson fell mortally wounded, the victim of a mistaken volley of smoothbore musketry by some confused North Carolinians. Eight days later, Sunday, May 10, 1863, the stricken general declared piously that he had always hoped to die on the Sabbath. “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees,” he said; then, as on so many marches and battlefields, he led the way. The war in Virginia—in fact the entire course of American history—veered onto an altered course.

The Confederacy could not survive the disaster; had there been any chance of independence, the loss of Lee’s “right arm” sealed the verdict. An Alabamian wrote prophetically of what many of his comrades were thinking: “This will have a gradeal to due with this war. I think the north will whip us soon.”

What combination of characteristics had enabled the sometime artillery major and academic mediocrity to carve so glittering a swath as a Confederate leader? There certainly was little in his appearance to contribute to the mystique. Storied military men, including Lee, for instance, often looked like powerful figures; Thomas Jackson was modestly handsome, a fraction under six feet tall, with “light bluish gray eyes” that often occasioned comment (”as brilliant as a diamond,” wrote one

A mien either graceful or militant, combined with his ordinarily agreeable appearance, might have made Jackson look something like his legend. In fact, though, he was taciturn and marginally disheveled. A Fredericksburg woman who attended church in 1863 with Jackson summarized the contrast: The general was “decidedly interesting if not handsome in his appearance…and very young for his age.…He has an embarrassed, diffident manner. Is a little deaf.” A member of the 4th Alabama wrote that Jackson looked like an “old Virginia farmer.” One of his Louisiana soldiers described him as “very ordinary looking” and reminiscent of a “Jew pedlar.” A staff officer from North Carolina complained in his diary: “What a common, ordinary, looking man he is! There’s nothing at all striking in his appearance.”

Federals captured by the general’s troops eagerly sought a glimpse of their world-famous foe; usually it was a letdown. One injured captive asked to be lifted up so he could see Mighty Stonewall. After a glance at the officer, in a dingy uniform, an old hat pulled low over his eyes, the Northerner sighed: “Oh my god! Lay me down!” Some Northern prisoners taken at Harpers Ferry expressed similar disappointment, but on quick reflection they agreed with a comrade who lamented, “I wish we’d had him.”

Whatever his popular image, his subordinates, almost without exception, did not like him. Senior generals under his command used unrestrained language about their treatment. A. P. Hill called him “that crazy old Presbyterian fool”; Richard S. Ewell referred to him as “that enthusiastic fanatic”; and Charles S. Winder, in diary entries across three days full of maneuver and battle, declared: “Jackson is insane.…growing disgusted with Jackson.…requesting to leave his command.”

Discomfort so pronounced suggests frustrated dealings with a superior either dishonest, lazy, selfishly ambitious, or simply stupid. Jackson was none of those things. What he was, instead, was painfully terse. In his sometimes awkward civilian dealings he once admitted, “I have no genius for seeming .” Officers—some of them major generals famous in their own right—came away from meetings horrified when he abruptly cut off even the most cursory forms of courteous discourse. The deadly determined Stonewall, his diligence reinforced by calm

The unusual personality that offended generals and colonels actually polished the patina of Stonewall’s growing legend. A pre-war civilian observer noted—as did many others—that Thomas Jackson “never smiled and talked only when he had something to say,” and added a remark about seeing “a most peculiar glint in his eye.” Observers of that indefinable something in Jackson’s gaze doubtless interpreted it more eagerly after he had become famous (famous for both his military prowess and his alleged eccentricity). It prompted one witness to suggest “that if Jackson were not a very good man he would be a very bad one.” Tales of unconventional habits, such as sucking on lemons or rampant hypochondria, inevitably grew in the telling.

Americans expect at least a discernible tincture of colorful peculiarity in their legends. Muttering about crazy Stonewall turned into gleeful recounting of his valuable eccentricities once the string of gaudy victories had begun. The man of course had changed not one whit in the meanwhile. A Macon, Georgia, newspaper typified the glib switch in a June 1862 column: “Sometime ago, we accused Jackson of being of unsound mind. Since that time, he has exhibited not the least symptom of improvement. In fact he gets worse and worse every day. Within the last two weeks he seems to have gone clean daft.…He has been raving, ramping, roaring, rearing, snorting and cavorting up and down the Valley, chawing up Yankees by the thousands.…Crazy or not, we but echo the voice of the whole Confederacy when we say ‘God bless Old Stonewall. ’”

For the men in the ranks who gasped and sweated through the general’s epic marches, his oddities likewise became lovable quirks and his insanity genius. The men discovered that a victory lay at the end of each march, usually without excessive cost in blood. Trading sweat for blood, and exertion for victory, made great good sense to them.

One aspect of Jackson’s businesslike style was his meticulousness. An intimate of the general at West Point (later a Confederate general himself) said aptly, “Jackson’s mind seemed to do its work rather by perseverance than quick penetration.” Stonewall had little of the acute intuition popularly presumed to be essential to great generalship—an attribute much mooted in nineteenth-century military texts as the French coup d’oeil or the German Fingerspitzengefuhl . Lacking the ability to master terrain at a glance, he employed several able

Another manifestation of his meticulousness was his rigorous insistence on gathering enemy property of all kinds, cataloguing it in full detail, and defending it at all costs. The official list of captured goods from the 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign enumerates saddles and shoes and blankets—and six handkerchiefs, two and three-quarter dozen neckties, and one bottle of red ink.

Wearing his new battle name of Stonewall, the general wrote soon after Manassas to his pastor in Lexington. Townspeople awaiting the mail eagerly sought to learn the contents of the envelope from their newly famous neighbor, but he mentioned the battle not at all. Instead he sent a check for the support of the Sunday school he had started (in contravention of law and social standard) for black youngsters. A few weeks later Jackson played host to a visiting minister from Lexington by putting the man of God up on his own cot; the general slept on the floor of the tent, “without bed or matrass,” the amazed visitor wrote.

Jackson’s letters to a confidant in the Confederate Congress included much about military affairs—requests for help with armaments and recruiting, suggestions for actions affecting the armies—but they also featured a steady flow of religious promptings. Should not the Congress forbid carrying the mail, to say nothing of actually delivering it, on the Sabbath? Why not ban distilleries, turning their copper tubing into cannon? (Jackson eschewed strong drink because, he said irrefragably, he liked the way it tasted.)

Deacon Jackson’s unflinching piety sometimes led him astray in military matters, as when he chose as his chief of staff a favorite Presbyterian cleric with precisely nothing to commend him for a staff role. In most instances, however, the divine guidance that Jackson perceived worked in his favor. In battle it became a Cromwellian religious fervor. (Comparing Jackson to the leader of the Roundheads was and remains a popular device.) Stonewall’s salient characteristics, both personal and military, profited from a calm certainty that he was doing God’s will: Flourish the sword of the Lord and of Gideon, and let the Philistines beware!

More than any other quality, Thomas Jackson displayed determination. That defining characteristic dominated his performance. On many a battlefield the unswerving resolve of one man had more effect than dozens of cannon or thousands of muskets. Earnest devotion to a single goal, no matter what the obstacles, made Jackson “the most one-idead man I

Examination of his storied campaigns reveals that Jackson’s military abilities at a tactical level, especially early in the war, were no more than ordinary. On the intermediate military plane that is called “operational,” midway between tactics and strategy, Jackson sometimes displayed marked skill. Strategically, he excelled, Grafting campaigns still studied as classics by military training programs. Even so, it is impossible to see in him the essential genius of a Frederick the Great or a Napoleon. What made him awesome in war was the clenchedjaw will that guided every decision at every level.

The Georgia soldier who wrote that “his presence was sufficient to strike terror to the heart of the enemy” captured the essence of the general’s image in the North. Jackson had become “the great dread of the Yankees,” in the delighted phrase of one of his men. A Virginia private, hoping that the Confederacy would find an equally capable hero after Jackson’s death, acknowledged sagely that even if it did, it would still take time for the Yankees “to learn to fear him” as they had the legendary Stonewall.

A century and a third after the death of Thomas J. Jackson, he remains an ogre only to tendentiously anti-Southern polemicists. The spectral aspect of his image continues to bemuse us, however, as we wonder at his unusual characteristics and his spectacular feats. This most compelling of 1860s warriors remains, in the memorable phrase of Stephen Vincent Benét, “Stonewall Jackson, wrapped in his beard and his silence.”