Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2000, Summer 2025 | Volume 51, Issue 5

Authors: Joseph J. Ellis

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2000, Summer 2025 | Volume 51, Issue 5

During the first contested presidential election in American history, the voters were asked to choose between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. In this millennial year, voters will choose between George W. Bush and Al Gore. At first blush, the caustic observation of Henry Adams appears indisputable: The American presidency stands as a glaring exception to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolutionary progress.

But straightforward comparisons between now and then are notoriously treacherous ventures, in part because those statesmen who have been eulogized and capitalized as Founding Fathers enjoy privileged treatment in our memories, in part because the political culture of the early American Republic was a fluid and formative bundle of improvisations. Nothing remotely resembling modern parties yet existed. The method of choosing electors to that odd inspiration called the Electoral College varied from state to state. Voters did not choose between two party tickets; they voted for the two best men, and the runner-up became Vice President. Once elected, the President did not regard himself as the leader of a political party so much as the bipartisan spokesman for the public interest.

Perhaps the most historically significant development during the Adams presidency was the emergence of party-based politics. This was the historical moment, in short, when the outlines of our modern system first began to congeal, the time when American politics began to move from then to now.

At the beginning of the story, however, no one envisioned the changes that were about to occur, and neither the institutions nor the vocabulary essential for making the transition were yet in place. In 1796, there were no political primaries, no party conventions with smoke-filled rooms. True enough, there were two identifiable political camps: the Federalists, who favored a more powerful central government and who had enjoyed the incalculable advantage of George Washington’s presiding presence as the central figure symbolizing national authority for the first eight years of the government’s existence, and the Republicans, the emerging opposition, who contested the authority of the federal government over domestic policy. But the chief qualification for the presidency was less a matter of one’s location within the political spectrum than a function of one’s revolutionary status. Memories of the hard-won battle for American independence were still warm, which meant that prospective candidates needed to possess revolutionary credentials earned during the crucial years between 1776 and 1783. Only those leaders were eligible who had stepped forward at the national level to promote the great cause when its success was still perilous and problematic.

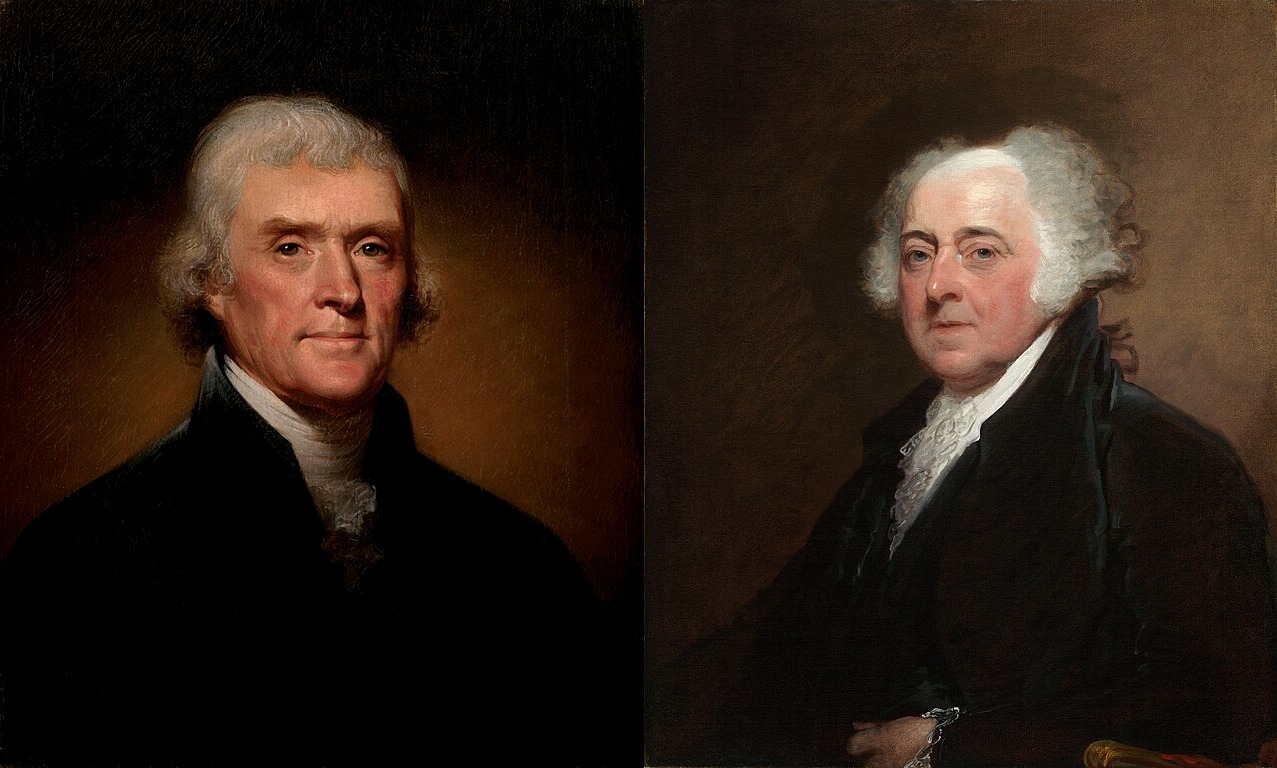

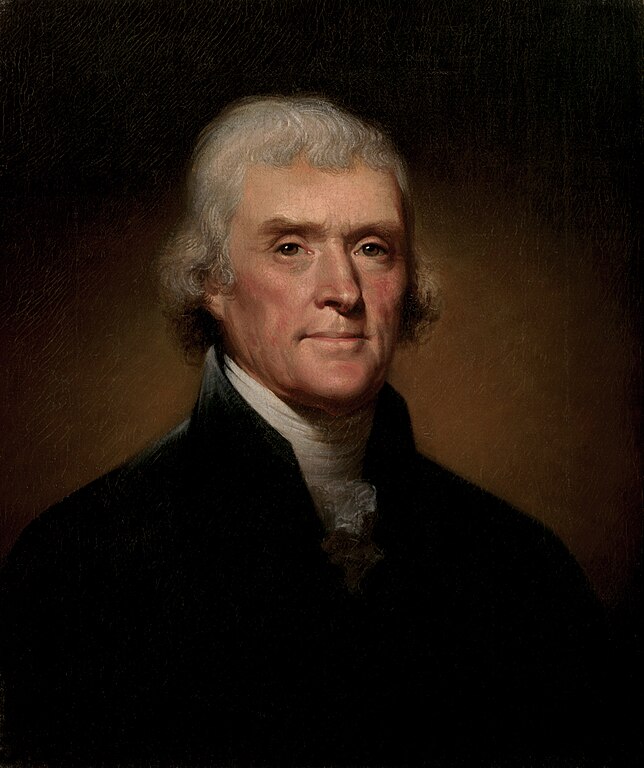

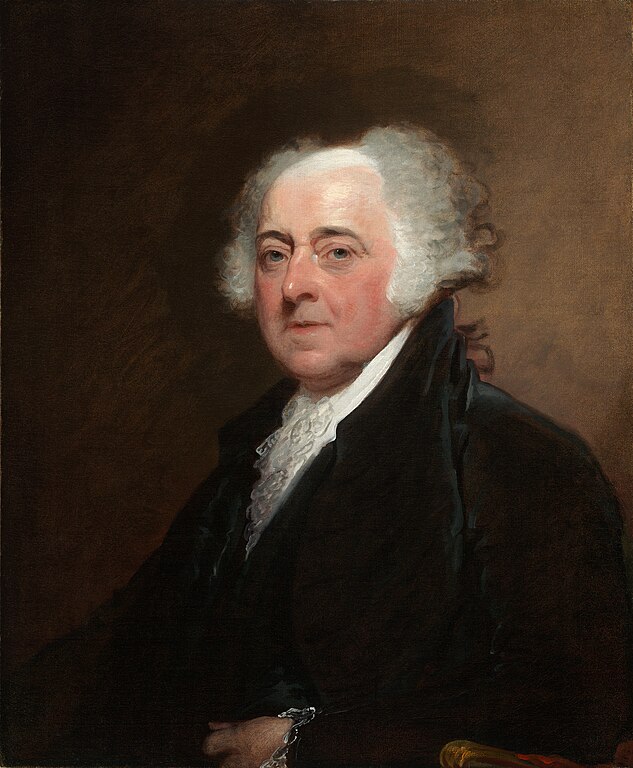

They were an incongruous pair, but everyone seemed to argue that history had made them into a pair. The incongruities leaped out for all to see: Adams the short, stout, candid-to-a-fault New Englander, Jefferson the tall, slender, elegantly elusive Virginian; Adams the highly combustible, ever-combative, mile-a-minute talker, whose favorite form of conversation was argument, Jefferson the always cool and self-contained enigma, who regarded argument as a violation of the natural harmonies he heard inside his own head. The list could go on: the Yankee and the Cavalier, the orator and the writer, the bulldog and the greyhound. Choosing between them seemed like choosing between the words and the music of the American Revolution.

As political rivals and personal friends, both men realized they were jockeying for position within the tremendous shadow of Washington, who was destiny’s choice as the greatest American of the age and therefore inherently irreplaceable. Adams’s strategy was to trade on the famous Adams-Jefferson friendship and to suggest a bipartisan administration. If no single leader could hope to fill the huge vacuum created by Washington’s departure, perhaps the reconstituted team of Adams and Jefferson might enjoy at least a fighting chance of sustaining the legacy of national leadership that Washington had established. Adams began to float the idea in letters to mutual friends like Benjamin Rush that if elected President, he intended to include Vice President Jefferson as a full partner in his administration.

Much like Adams, Jefferson was also preoccupied with the long shadow of George Washington. As he confided to James Madison: “The President [Washington] is fortunate to get off just as the bubble is bursting, leaving others to hold the bag. Yet, as his departure will mark the moment when the difficulties begin to work, you will see, that they will be ascribed to the new administration. …” Jefferson was certain that “no man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it.” While strolling the grounds of Monticello with a French visitor, he expanded on his strategic sense of the intractable political realities: “In the present situation of the United States, divided as they are between two parties, which mutually accuse each other of perfidy and treason, … this exalted station [the presidency] is surrounded

Jefferson got his wish. In early February 1797, when the electoral votes were counted, they revealed that in a razor-thin victory, Adams had prevailed, 71-68. The question facing Jefferson now became painfully clear: As the newly elected Vice President, should he join hands with his old friend to establish a bipartisan executive team? As was his custom, Jefferson turned to his most trusted political confidant for advice, and James Madison provided a brutally realistic answer: “Considering the probability that Mr. A’s course of administration may force an opposition to it from the Republican quarter, and the general uncertainty of the posture which our affairs may take, there may be real embarrassments from giving written possession to him, of the degree of compliment and confidence which your personal delicacy and friendship have suggested.” In short, Jefferson must not permit himself to be drawn into the policymaking process of the Adams administration, lest it compromise his role as leader of the Republican opposition.

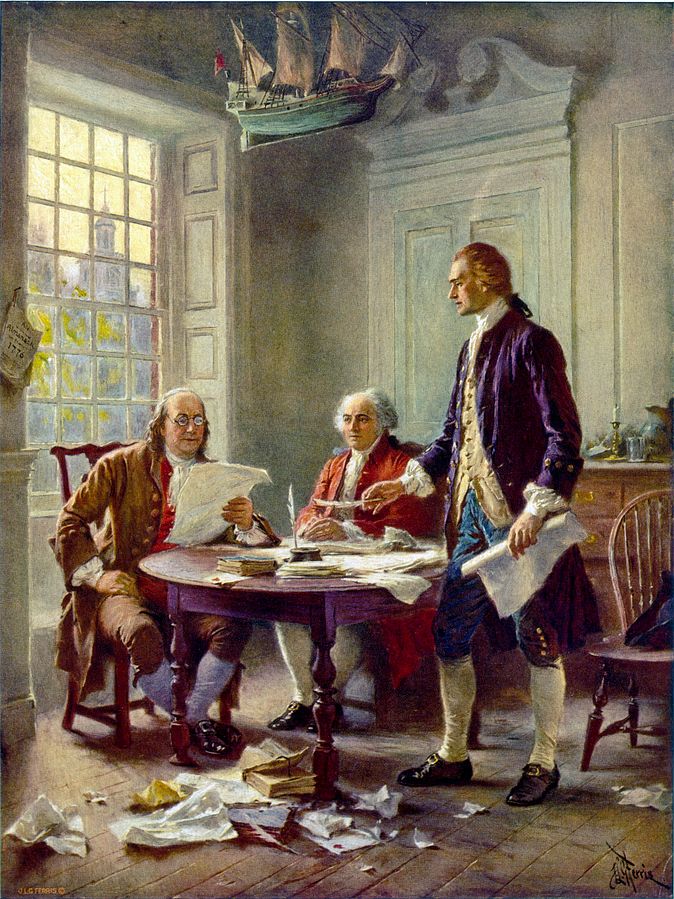

The decision played out in a dramatic face-to-face encounter. On March 6, 1797, Adams and Jefferson dined with Washington at the presidential mansion in Philadelphia. Adams learned that Jefferson was unwilling to join the cabinet; Jefferson learned that Adams had been battling with his Federalist advisers, who opposed a vigorous Jeffersonian presence in the administration. They left the dinner together and walked down Market Street to Fifth, two blocks from the very spot where Jefferson had drafted the words of the Declaration of Independence that Adams had so forcefully defended before the Continental Congress almost twenty-one years earlier. As Jefferson remembered it later, “We took leave, and he never after that said one word to me on the subject or ever consulted me as to any measure of the government.”

A few days later, at his swearing-in ceremony as vice president, Jefferson joked about his rusty recall of parliamentary procedure, a clear sign that he intended to spend his time in the harmless business of monitoring debates in the Senate. After Adams was sworn in as president on March 4, he reported to Abigail that Washington had murmured under his breath: “Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which of us will be happiest.” Predictably, the sight of Washington leaving office attracted the bulk of the commentary in the press. Adams informed his beloved Abigail that it was like “the sun setting full-orbit, and another rising (though less splendidly).” Jefferson was on the road back to Monticello immediately after the inaugural ceremony, setting up the Republican government-in-exile, waiting for the inevitable catastrophes to befall the Presidency of his old friend. As for Adams himself, without Jefferson as a colleague, with a Federalist cabinet filled with men loyal to Hamilton, he was left alone with

Beyond the daunting task of following the greatest hero in American history, Adams faced a double dilemma. On the one hand, the country was already waging an undeclared war, called the Quasi-War, against French privateers in the Atlantic and Caribbean. Should the United States declare war on France or seek a diplomatic solution? Adams, like Washington, was committed to American neutrality at almost any cost, but he coupled this commitment with a buildup of the American Navy, which would enable the United States to fight a defensive war if negotiations with France broke down.

On the other hand, the ongoing debate between Federalists and Republicans had degenerated into unrelenting ideological warfare in which each side sincerely saw the other as traitor to the core principles of the American Revolution. The political consensus that had held together during Washington’s first term and had then begun to fragment into Federalist and Republican camps over the Jay Treaty broke down completely in 1797. Jefferson spoke for many of the participants caught up in this intensely partisan and nearly scatological political culture when he described it as a fundamental loss of trust between former friends. “Men who have been intimate all their lives,” he observed, “cross the street to avoid meeting, and turn their heads another way, lest they should be obliged to touch hats.” He first used the phrase a wall of separation —which would later become famous as his description of the proper relation between church and state—to describe the political and ideological division between Federalists and Republicans.

The very idea of a legitimate opposition did not yet exist in the political culture of the 1790s, and the evolution of political parties was proceeding in an environment that continued to regard the term party as an epithet. In effect, the leadership of the revolutionary generation lacked a vocabulary adequate to describe the politics they were inventing. And the language they inherited framed the genuine political differences and divisions in personal terms that only exacerbated their nonnegotiable character. “You can witness for me,” Adams wrote to his son John Quincy concerning Jefferson’s opposition, “how loath I have been to give him up. It is with much reluctance that I am obliged to look upon him as a man whose mind is warped by prejudice.

At the domestic level, then, Adams inherited a supercharged political atmosphere every bit as ominous and intractable as the tangle on the international scene. It was a truly unprecedented situation in several senses: His vice president was in fact the leader of the opposition party; his cabinet was loyal to the memory of Washington, which several members regarded as embodied now in the person of Alexander Hamilton, who was officially retired from the government altogether; political parties were congealing into doctrinaire ideological camps, but neither side possessed the verbal or mental capacity to regard the other as anything but treasonable; and finally, the core conviction of the entire experiment in republican government—namely, that all domestic and foreign policies derived their authority from public opinion—conferred a novel level of influence on the press, which had yet to develop any established rules of conduct or standards for distinguishing rumors from reliable reporting. It was a recipe for political chaos that even the indomitable Washington would have been hard pressed to control.

What happened as a result was highly improvisational and deeply personal. Adams virtually ignored his cabinet, most of whom were more loyal to Hamilton anyway, and fell back on his family for advice, which in practice made Abigail his unofficial one-woman staff. Jefferson continued his partnership with Madison, the roles now reversed, with Jefferson assuming active command of the Republican opposition from the seat of government in Philadelphia and Madison dispensing his political wisdom from retirement at Montpelier. While the official center of the government remained in the executive and congressional offices at Philadelphia, the truly effective centers of power were located in two political partnerships based on personal trust. Having failed to revive-the great collaboration of the revolutionary era, Adams and Jefferson went their separate ways with different intimates.

There was an almost tribal character to the Adams collaboration. Adams himself, while vastly experienced as a statesman and diplomat, had no experience whatsoever as an executive. He had never served as a governor like Jefferson or as a military commander like Washington. And he regarded the role of party leader of the Federalists as not just unbecoming but utterly incompatible with his responsibilities as President, which were to transcend party squabbles in the Washington mode and reach decisions like a “patriot king” whose sole concern was the long-term public interest. As a result, the notion that he was supposed to manage the political factions in Congress or in his cabinet never even occurred to him. Instead, he would rely on his own judgment and on the advice of his family and trusted friends.

Abigail was his chief domestic minister-without-portfolio. In a very real sense, Adams did not have a domestic policy; indeed, he believed that paying any attention to the shifting currents of popular opinion and the raging party battles in the press violated his proper posture as President, which was to remain oblivious of such swings in the national mood. Abigail tended to reinforce this belief in executive independence. Jefferson, she explained, was like a willow who bent with every political breeze. Her husband, on the other hand, was like an oak: “He may be torn up by the roots, or break, but he will never bend.”

Nevertheless, she followed the highly partisan exchanges in the Republican newspapers and provided her husband with regular reports on the machinations and accusations of the opposition. When an editorial in the pro-Republican Aurora described Adams as “old, querelous, Bald, blind, [and] crippled,” Abigail joked that she alone possessed the intimate knowledge to testify about his physical condition. She relished reporting the Fourth of July toast: “John Adams. May he, like Samson , slay thousands of Frenchmen with the jawbone of Jefferson.” She passed along gossip circulating in the streets of Philadelphia about plans to mount pro-French demonstrations, allegedly orchestrated by “the grandest of all grand Villains, that traitor to his country—the infernal Scoundrel Jefferson.” She predicted that Jefferson and his Republican friends “will … take ultimately a station in the public’s estimation like that of the Tories in our Revolution.”

Although we can never know for sure, there is considerable evidence that Abigail played a decisive role in persuading Adams to support passage of those four pieces of legislation known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These infamous statutes, unquestionably the biggest blunder of the Adams Presidency, were designed to deport or disenfranchise foreign-born residents, mostly Frenchmen, who were disposed to support the Republican party, and to make it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States. …” Adams went to his grave claiming that these laws never enjoyed his support, that he had signed them grudgingly and reluctantly.

All this was true enough, but sign them he did, despite his own reservations and against the advice of the moderate Federalists like John Marshall. Abigail, on the other hand, felt no compunctions. “Nothing will have an Effect until congress passes a Sedition Bill,” she wrote her sister in the spring of 1798. “The wrath of the public ought to fall upon their [the Republican editors’] devoted Heads.” In a later letter, she went on to say, “In any other Country [Benjamin Franklin] Bache [editor of the

Ironically, the most significant—and in the long run the most successful—decision of the Adams presidency occurred when Abigail was recovering from a bout with rheumatic fever back in Quincy. Federalists who opposed the policy attributed it to her absence. This was Adams’s apparently impulsive decision, announced on February 18, 1799, to send another peace delegation to France. (The first delegation had failed when the French government brazenly demanded a bribe before negotiating.) Theodore Sedgwick, a Federalist leader in Congress, claimed to be “thunderstruck” and summed up the reaction of his Federalist colleagues: “Had the foulest heart and the ablest head in the world … have been permitted to select the most … ruinous measure, perhaps it would have been precisely the one which has been adopted.” Timothy Pickering, the disloyal Secretary of State, whom Adams had come to despise, also described himself as thunderstruck and offered a perceptive reading of Adams’s motives: ”… it was done without any consultation with any member of the government and for a reason truly remarkable—because he knew we should all be opposed to the measure .” The stories circulating in the Philadelphia press suggested that Adams had acted impulsively because his politically savvy wife had not been available to talk him out of it. (For the preceding two months Adams had in fact been complaining in public and private that he was no good as a “solitudionarian” and he “wanted my talkative wife.”) Abigail had noted an editorial in Porcupine’s Gazette regretting her absence. “I suppose,” she wrote her husband, “they will want somebody to keep you warm.” The announcement of the new peace initiative then gave added credibility to the charge that without Abigail, Adams had lost either his balance or his mind. Adams joked about these stories. “This ought to gratify your vanity,” he wrote Abigail, “enough to cure you!” For her part, Abigail returned the joke but with a clear signal of support: “This was pretty saucy, but the old woman can tell them they are mistaken, for she considers the measure a master stroke of policy.…” This has pretty much been the verdict of history, for the peace delegation Adams appointed eventually negotiated a diplomatic end to the Quasi-War. Adams’s decision became the first substantive implementation of Washington’s message in the

It was the trademark Adams style, which might be described as enlightened perversity. He actually sought out occasions to display, often in conspicuous fashion, his capacity for self-sacrifice. If a decision was politically unpopular, well, that only confirmed that it must be right. He had defended the British troops accused of the Boston Massacre, insisted upon American independence in the Continental Congress a full year before it was fashionable, and argued for a more exalted conception of the Presidency despite charges of monarchical tendencies. It all was part of the Adams pattern, an iconoclastic and contrarian temperament that relished alienation. (John Quincy and then great-grandson Henry exhibited the same pattern over the next century, suggesting that the predilections resided in the bloodstream.) The political conditions confronting the Presidency in 1798 were tailor-made to call forth his vintage version of virtue. All the domestic and international challenges facing the Adams Presidency looked entirely different to Jefferson and Madison. Once they decided to reject Adams’s overture and set themselves up as the leaders of the Republican opposition, they closed ranks around their own heartfelt convictions and interpreted the foreign and domestic crises confronting Adams as heaven-sent opportunities to undermine the Federalist party, which they sincerely regarded as an organized conspiracy against the true meaning of the American Revolution. “As to do nothing, and to gain time, is everything with us,” Jefferson wrote to Madison, the very intractability of the French question and “the sharp divisions within the Federalist camp” worked to their political advantage. For the Republican agenda to win, the Federalist agenda needed to fail. Although Adams never fitted comfortably into either party category and seemed determined to alienate himself from both sides, as the elected leader of the Federalists he became the chief target of their organized opposition. Jefferson’s nearly Herculean powers of self-denial helped keep the Republican cause pure, at least in the privacy of his own mind. In 1798 he commissioned James Callender, a notorious scandalmonger who had recently broken the story on Hamilton’s adulterous affair with Maria Reynolds, to write a libelous attack on Adams. In The Prospect Before Us, Callender delivered the goods, describing Adams as “a hoary headed incendiary” who was equally determined on war with France and on declaring himself President-for-life—both suggestions were preposterous—with John Quincy lurking in the background as his biological successor to “the American throne.” When confronted with the charge that despite his position as Vice President, he had paid Callender to write diatribes against the President, Jefferson claimed to know nothing about it. Callender subsequently published Jefferson’s incriminating letters, proving his complicity, and the vice president seemed genuinely surprised at the revelation, suggesting that for Jefferson the deepest secrets were not the ones he kept from his enemies but the ones he kept from himself. By modern standards, Jefferson’s active role in promoting anti-Adams propaganda and his complicity in leaking information to pro-French enthusiasts like Bache were impeachable offenses that verged on treason. But, only ten years after the passage and ratification of the Constitution, what were treasonable or seditious acts remained blurry judgments without the historical sanction that only experience could provide. Lacking a consensus on what the American Revolution had intended and what the Constitution had settled, Federalists and Republicans alike were afloat in a sea of mutual accusations and partisan interpretations. The center could not hold because it did not exist. There are only a few universal laws of political life, but one of them guided the Republicans during the last year of the Adams presidency—namely, never interfere when your enemies are busily engaged in flagrant acts of self-destruction. As soon as the Federalists launched their prosecutions of Republican editors and writers under the Sedition Act —a total of 14 indictments were filed—it became clear that the prosecutions were generally regarded as persecutions. Most of the defendants became local heroes and public martyrs. Madison quickly concluded that “our public malady may work its own cure,” meaning that the spectacle of Federalist lawyers descending upon the Republican opposition with such blatantly partisan accusations only served to create converts to the cause they were attempting to silence. What Jefferson had described as “the reign of witches” even began to assume the shape of a political comedy in which the joke was on the Federalists. In New Jersey, for example, when a drunken Republican editor was charged with making a ribald reference to the President’s posterior, Republican commentators argued that

But this delectable morsel of scandal, which was confirmed as correct beyond any reasonable doubt only by DNA studies done in 1998, did not arrive in time to help Adams in the presidential election of 1800. Indeed, Adams’s string of bad luck or poor timing, call it what you will, persisted to the end. The peace delegation he dispatched to France so single-handedly negotiated a treaty ending the Quasi-War, but the good news arrived too late to influence the election. Given this formidable array of bad luck, bad timing, and the highly focused political strategy of his Republican enemies, Adams did surprisingly well when all the votes were counted. He ran ahead of the Federalist candidates for Congress, who were swept from office in a Republican landslide. Outside of New York, he even won more electoral votes than he had in 1796. But thanks in great part to the deft political maneuverings of Aaron Burr, all twelve of New York’s electoral votes went to Jefferson. As early as May of 1800, Abigail, the designated vote-counter on the Adams team, had predicted that “New York will be the balance in the scaile , scale scaill (is it right now? it does not look so).” Though she did not know how to spell scale , she knew where the election would be decided. In the final tally, her husband lost to the tandem of Jefferson and Burr, 73-65. When Madison declared that the Republican cause was now “completely triumphant,” he meant not only that they had won control of the presidency and the Congress but also that the Federalist party was in complete disarray. Though pockets of Federalist power remained alive in New England for more than a decade, as a national movement it was a spent force. But no one quite knew what the Republican triumph meant in positive terms for the national government. It was clear, however, that a particular version of politics and above-the-fray political leadership embodied in the Washington and Adams administrations had been successfully opposed and decisively defeated. The Jefferson-Madison collaboration was the politics of the future. The Adams collaboration was the politics of the past. What died was the presumption, so central to Adams’s sense of politics and of himself, that there was a long-term

Neither member of the Adams team could ever comprehend this historical transition as anything other than an ominous symptom of moral degeneration. “Jefferson had a party,” Adams observed caustically, “Hamilton had a party, but the commonwealth had none.” If the Adams brand of statesmanship was now an anachronism—and it was—then he wanted the Adams Presidency to serve as a fitting monument to its passing. He could leave office in the knowledge that his discredited policies and singular style had actually worked. As he put it, he had “steered the vessell … into a peaceable and safe port.” The last major duty of the Adams collaboration was to supervise the transition of the federal government to its permanent location on the Potomac. Though the entire archive of the Executive branch required only seven packing cases, Abigail resented the physical burdens imposed by this final chore, as well as the cold and cavernous and still unfinished rooms of the presidential mansion. For several weeks it was not at all clear whether Jefferson would become the next occupant, because the final tally of the electoral vote had produced a tie between him and Burr. Rumors circulated that Adams intended to step down from office in order to permit Jefferson, still his vice president, to succeed him. Adams let out the word that Jefferson was clearly the voters’ choice and the superior man, that Burr was “like a balloon, filled with inflammable air.” In the end the crisis passed when, on the thirty-sixth ballot, the House voted Jefferson into office. Despite all the accumulated bitterness of the past eight years, and despite the political wounds Jefferson had inflicted over the past four years on the Adams presidency, Abigail insisted that her husband invite their “former friend” for cake and tea before she departed for Quincy a few weeks before the inauguration ceremony. No record of the conversation exists, though Jefferson had already apprised Madison that he knew the Adamses well enough to expect “dispositions liberal and accommodating.” On March

Abigail managed to have the last word on the thoroughly modern and wholly partisan political world that Jefferson’s Presidency inaugurated. In 1804, after he attempted to open a correspondence with her and, so he hoped, with her husband, Abigail cut him short with a one-sentence rejection: “Faithful are the wounds of a friend.” It was a fitting epitaph for the Adams presidency.