Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 2003 | Volume 54, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 2003 | Volume 54, Issue 4

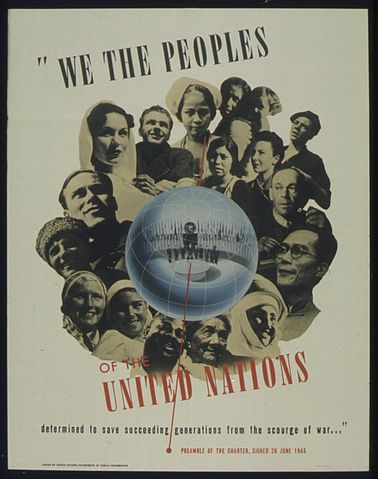

In the months before the war to overthrow Saddam Hussein, two words kept cropping up in the vocabulary of its opponents: sovereignty and legitimacy. The war, they said, would threaten the sovereignty of an autonomous state (the Ba'ath party’s Iraq), and it would lack the legitimacy conferred by the backing of the United Nations. As one journalist put it, an invasion would be “the first test of the new doctrine … that the United States has the right to invade sovereign countries and overthrow their governments. … At stake is not just the prospect of a devastating war, but the very legitimacy of an international system developed over the past century that, despite its failings, has created at least some semblance of global order and stability.”

Such concerns were very widely felt. Robert Kuttner, the co-editor of The American Prospect, wondered if “other sovereign nations are prepared to accept the status of cattle.” Jacques Chirac, the president of France, warned against “throwing off the legitimacy of the United Nations.” Even Colin Powell conceded that the UN would have to become involved in rebuilding Iraq for the sake of “international legitimacy.”

There is a problem with these concerns, a contradiction at the heart of the United Nations. It’s a paradox with roots that stretch back to Woodrow Wilson’s 1918 plan for a world without war, and to Eleanor Roosevelt’s valiant struggle after World War II to place the rights of individuals above the rights of states. The problem is simply stated: Sovereignty and legitimacy are crucial to modern liberal internationalism, and so is the defense of human rights. Yet they can be completely at cross-purposes. Suppose a sovereign state willfully violates the human rights of its citizens, and the legitimate international community fails to intervene? Which is more important, international law and the equality of states or the rights of individuals?

The principle of sovereign equality can be traced back across more than three centuries to 1648 and the Treaty of Westphalia. Besides bringing an end to the Thirty Years’ War, Westphalia formed the cornerstone of what became the modern system of states. In giving independence to the nations that had made up the Holy Roman Empire, Westphalia went a long way toward establishing the general belief that the internal affairs of a country—the religion it favors, the freedoms it allows—were the legitimate concern only of its own government. According to this modern notion of sovereignty, a prince was constrained in what he could do outside his nation, but he essentially enjoyed free rein within it.